In this piece, we provide an update on:

US economy and job market

Tariff and Inflation Risks

Market correction and/or repeat of Dotcom Bubble

“The Powell struggle”, rate cuts and housing unlock

Bond yields and housing unlock and cyclical sectors

US - China Talk

Macro Positioning

Our diagnoses and predictions have mostly borne out to be accurate:

Tariff inflation risks were overstated [Yes]

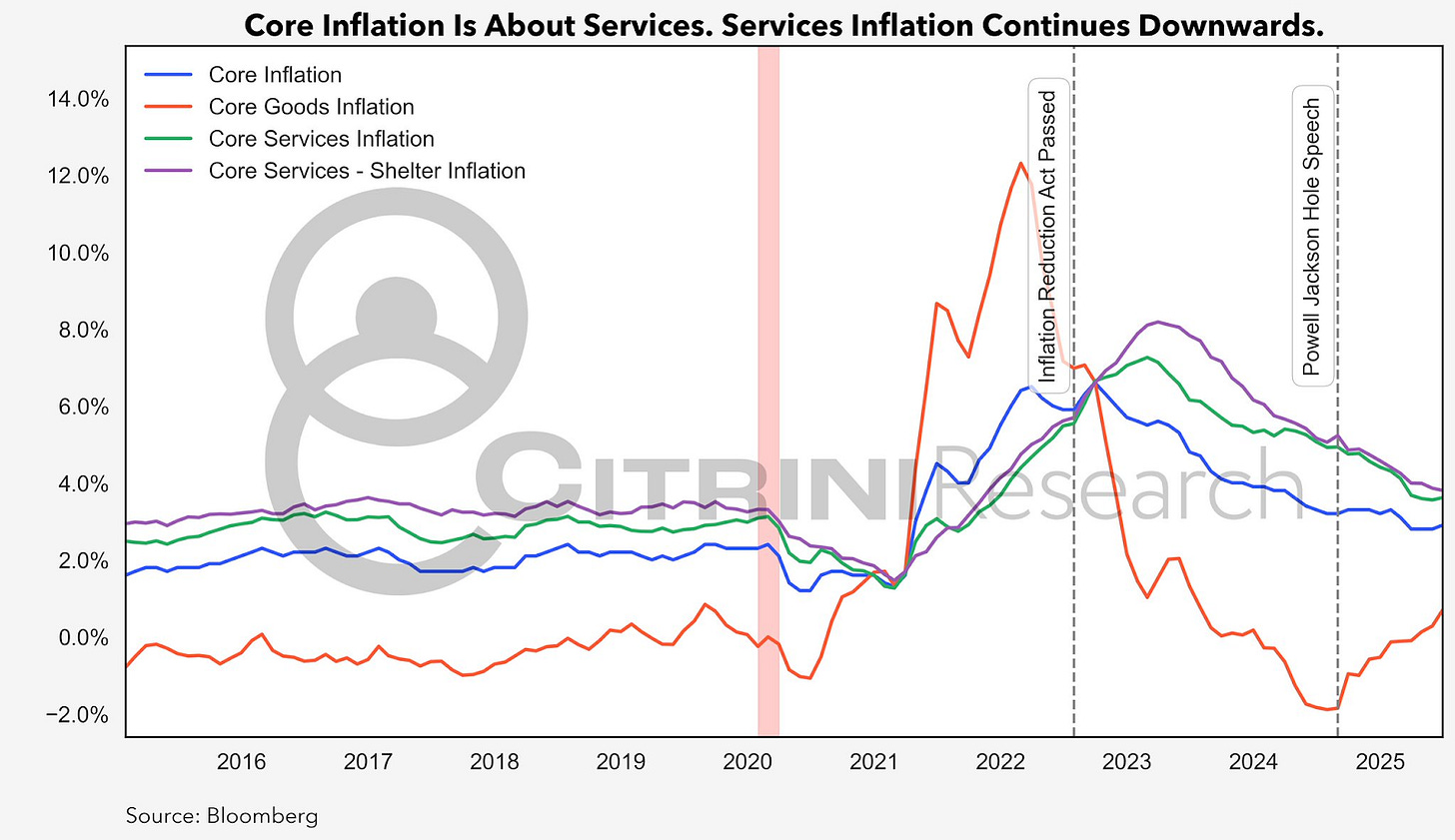

Services disinflation continues and overwhelms goods inflation [Yes]

General US economic resilience with a softening labor market [Yes]

The Fed makes good news insurance cuts [Not quite, yet.]

US - China tension continues to take off-ramps [Yes]

Rare earth and the importance of strategic leverage [Yes]

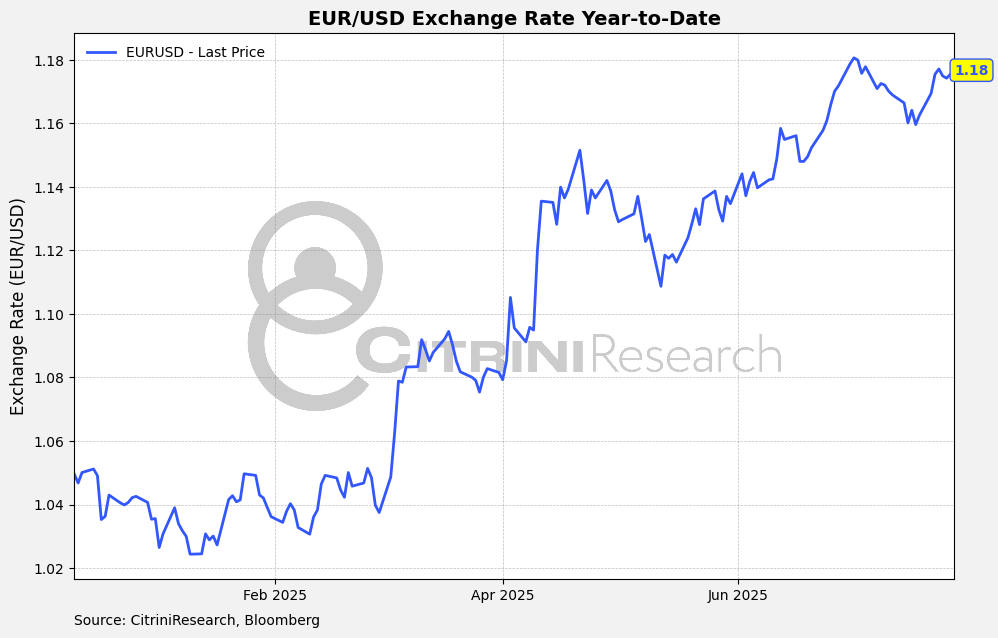

European outperformance in FX & Equities would taper off [No/Not yet]

Our last macro memo broke our 100% YTD hit rate in STIR trading - we managed to catch a bit of a move up in Z5 but haven’t seen any follow through

The Upshot

The US economy will continue slowing without breaking

Overall inflation flat or lower despite tariff effects on goods prices

“The Powell Struggle” leads to fiscal - monetary convergence

Tariff uncertainty resolves

The Fed to signal openness to rate cuts

Falling long yields to unlock housing market

In June, we wrote that the U.S. economy was “humming along.” Two months later, that characterization still fits - there is a distinct lack of fresh macro drama, the likes of which prompted us to begin doing monthly macro updates. Since autumn 2024 our stance has been consistent: headline growth remains resilient even as the labor market cools and disinflation progresses. The intermediate calls that flowed from that thesis have largely been validated, but the macro trading regime has shifted. For the past two years, successful macro traders have largely been those that were focused on fading overreactions at key moments in rates and FX.

President Trump’s recent showdown with Fed Chair Jerome Powell—what we call The Powell Struggle—marks the end of that lull. We now anticipate a transition from Trump’s failed public pressure campaign to a more strategic effort to engineer macro conditions that justify rate cuts. With inflation cooling, the trade war de-escalating, and dovish voices gaining traction within the Fed, we expect the door to policy easing to open soon. This emerging political–monetary convergence sets the stage for a gradual decline in long-term interest rates.

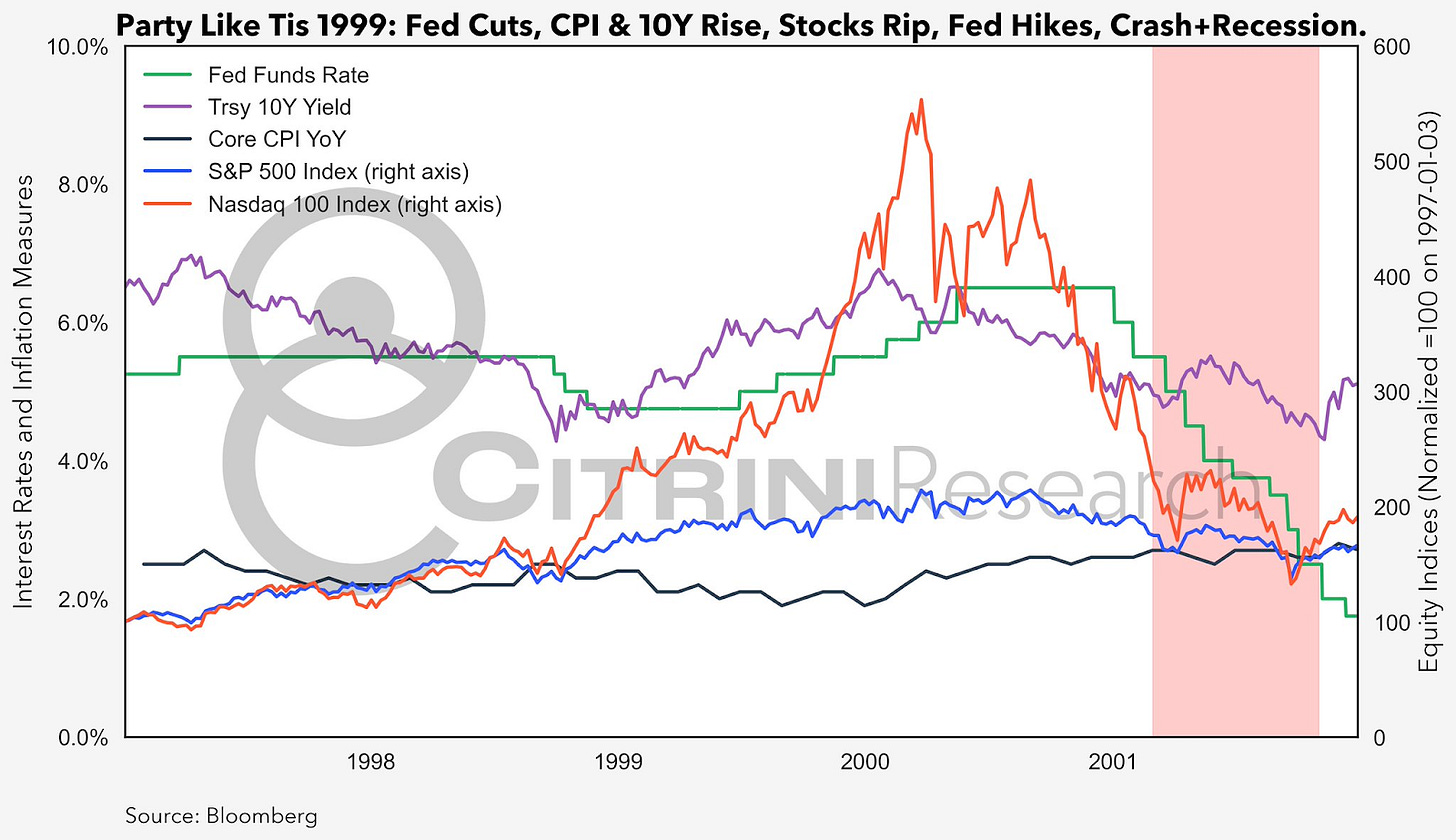

As summer winds down, both the economy and the market stand at a crossroads. Should we expect a re-acceleration of the economy and an end to the two and half year favorable disinflation process? In terms of the stock market, do we see a macro catalyst that triggers a long-awaited pullback? Or will markets continue to grind higher on secular bullish narratives like continued AI capex spending, deregulation, a more supportive tax policy and crypto adoption against a still-supportive macro backdrop. In the latter scenario - a continued strong economy with companies riding the coattails of secular trends despite elevated valuations - we start to get distinct vibes for the potential replay of the Dotcom Bubble that we alluded to in January.

US Economy and Job Market Check-In

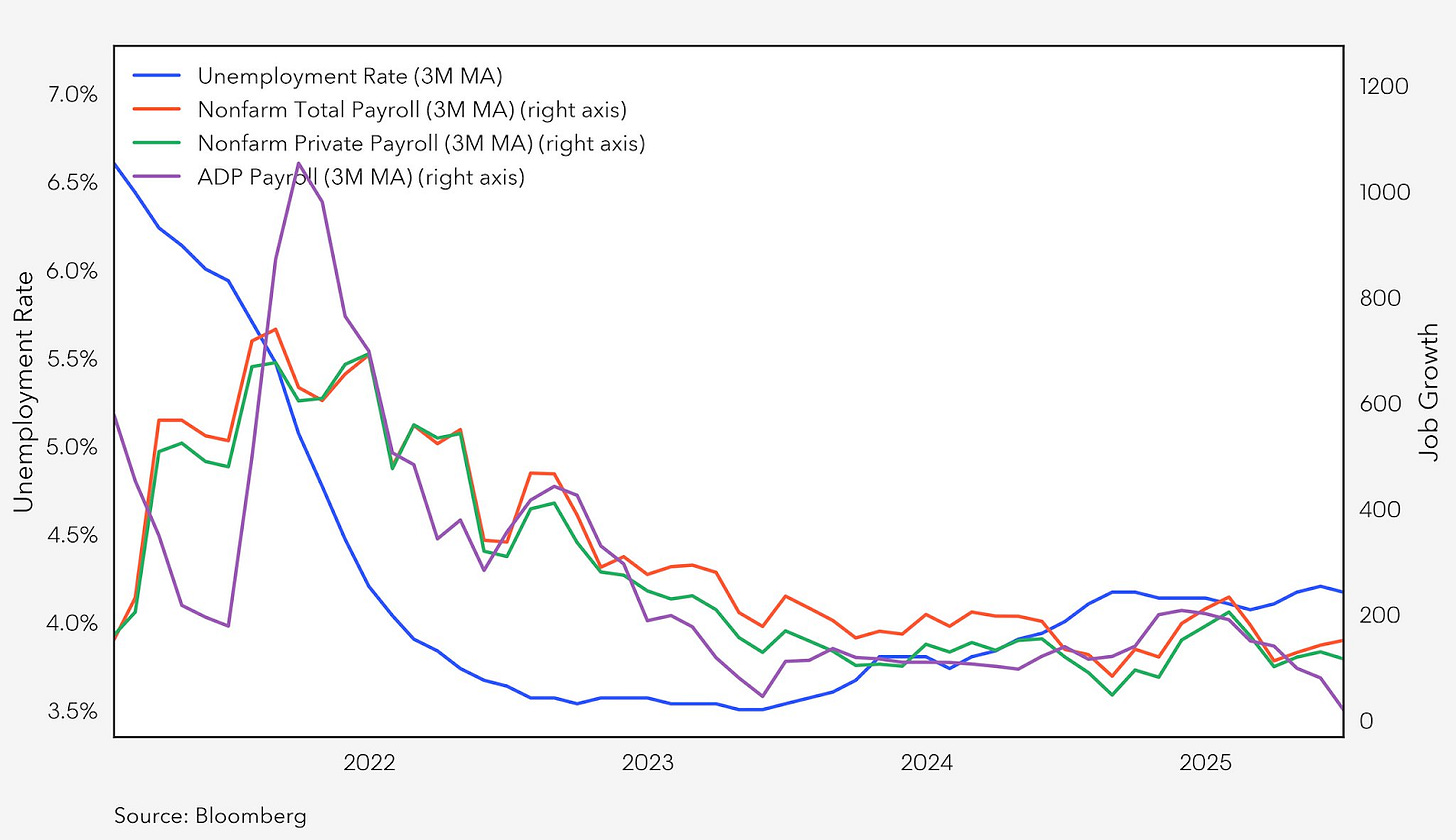

The U.S. economy still appears resilient, but the labor market is quietly cooling and the disinflation trend remains intact. The overall macro picture looks consistent with lower interest rates. Headline indicators look healthy, but most net new hiring now comes from government and low‑productivity service areas such as health care.

Unemployment is still near cycle lows, creating a “nobody fired, nobody hired” dynamic. However, worryingly, at the same time, the jobless rate for recent college graduates has climbed to a ten‑year high. While the unemployment rate is typically a key indicator of economic strength, it is now less indicative (at least for the Fed) due to immigration.

Other historically reliable labor market indicators continue to show signs of gradual softening. Both job openings and wage growth have been trending lower. The official job openings rate has hovered around 4.5% - a threshold below which the unemployment rate has historically begun to rise. Meanwhile, private data from Indeed points to a further decline in job postings, suggesting that the official figures may soon follow suit.

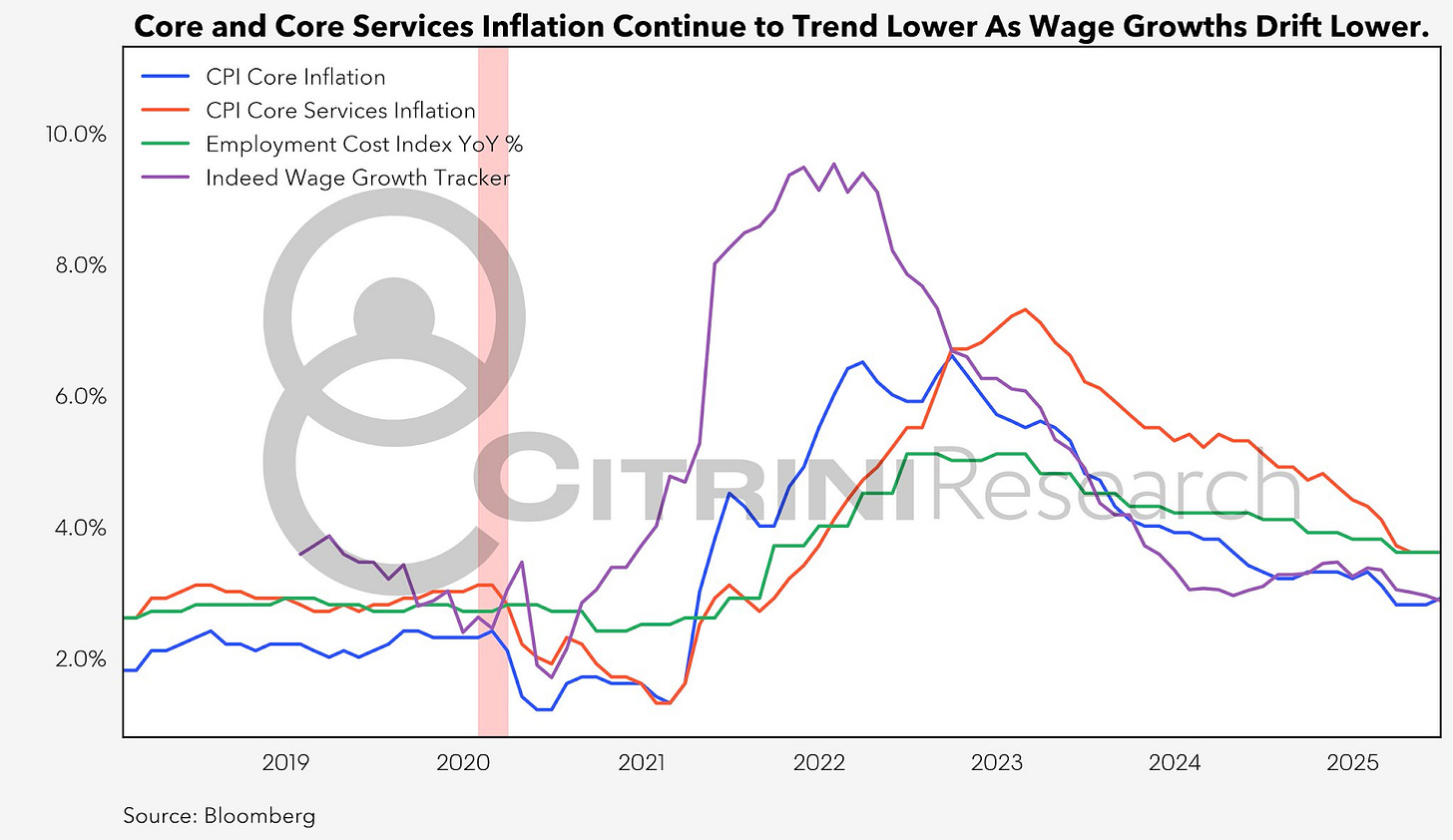

For those already employed, wage growth continues to decline across job segments providing further evidence of a cooling labor market. While some argue that this slowdown should primarily affect job switchers, not job holders, economic logic suggests otherwise: when employers face a surplus of available workers, they have little incentive to offer higher wages, even to those already on the payroll. The broad-based wage deceleration underpins our view that rent inflation will remain contained - a view still supported by recent data:

Unlike the halcyon days of our “Schrodinger’s Recession” dynamic, in which the economy roared along and the only “recession” came from overzealous market front-running, the U.S. labor market does seem to be at a crossroads now. The potential to either soften further or re-accelerate is present and will be determined going forward by the coordination (or lack thereof) between fiscal and monetary policy, a point we will return to in a later section

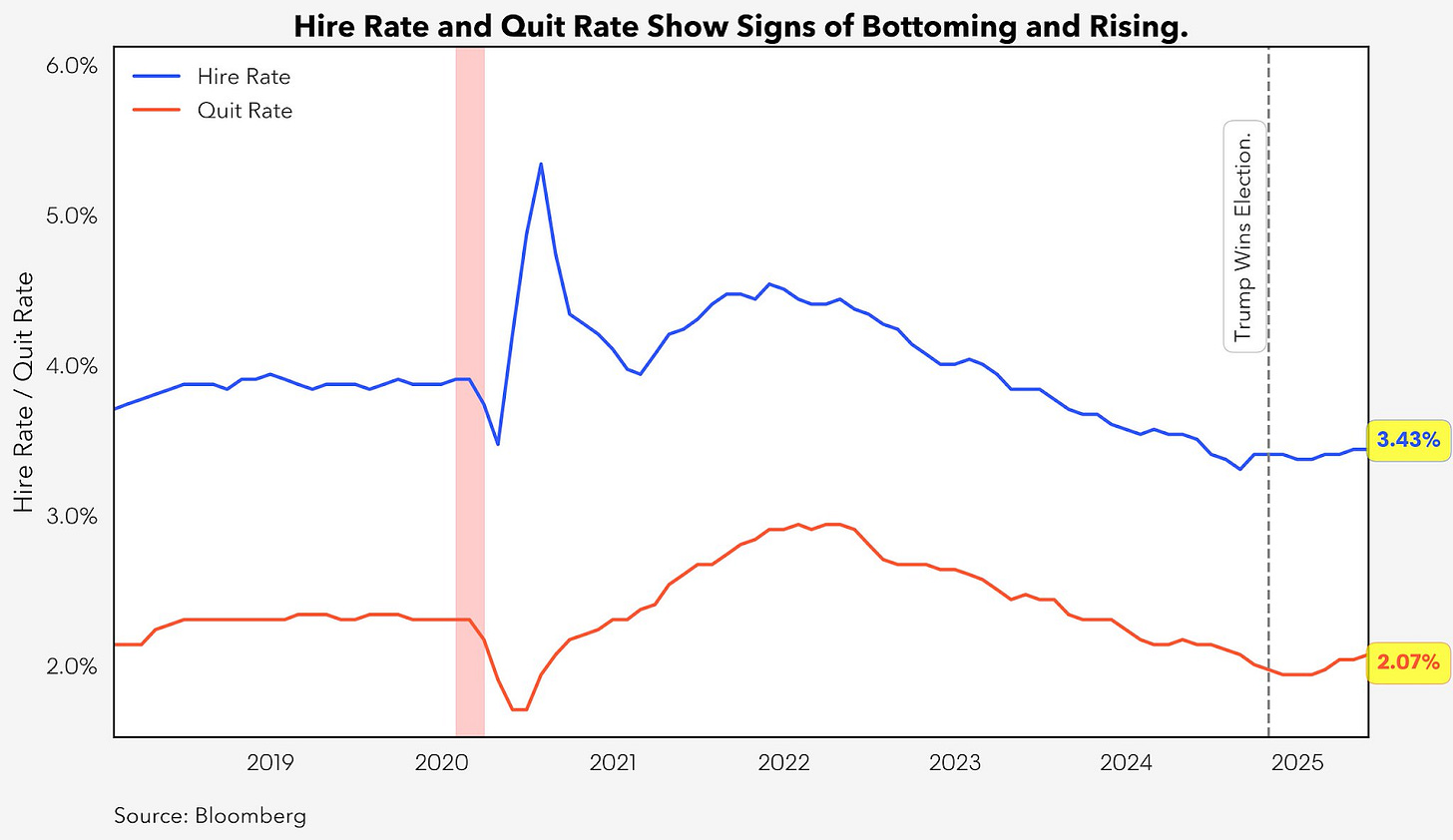

Labor market uncertainty is compounded by the Trump administration’s perceived “run-it-hot” fiscal stance, aggressive tariff agenda, and mass deportation policy - each of which carries complex, and potentially conflicting, economic effects. In this context, we are closely monitoring for signs of reacceleration and reflation. One early indicator of renewed labor market tightness is the recent uptick in both the hiring and quit rates.

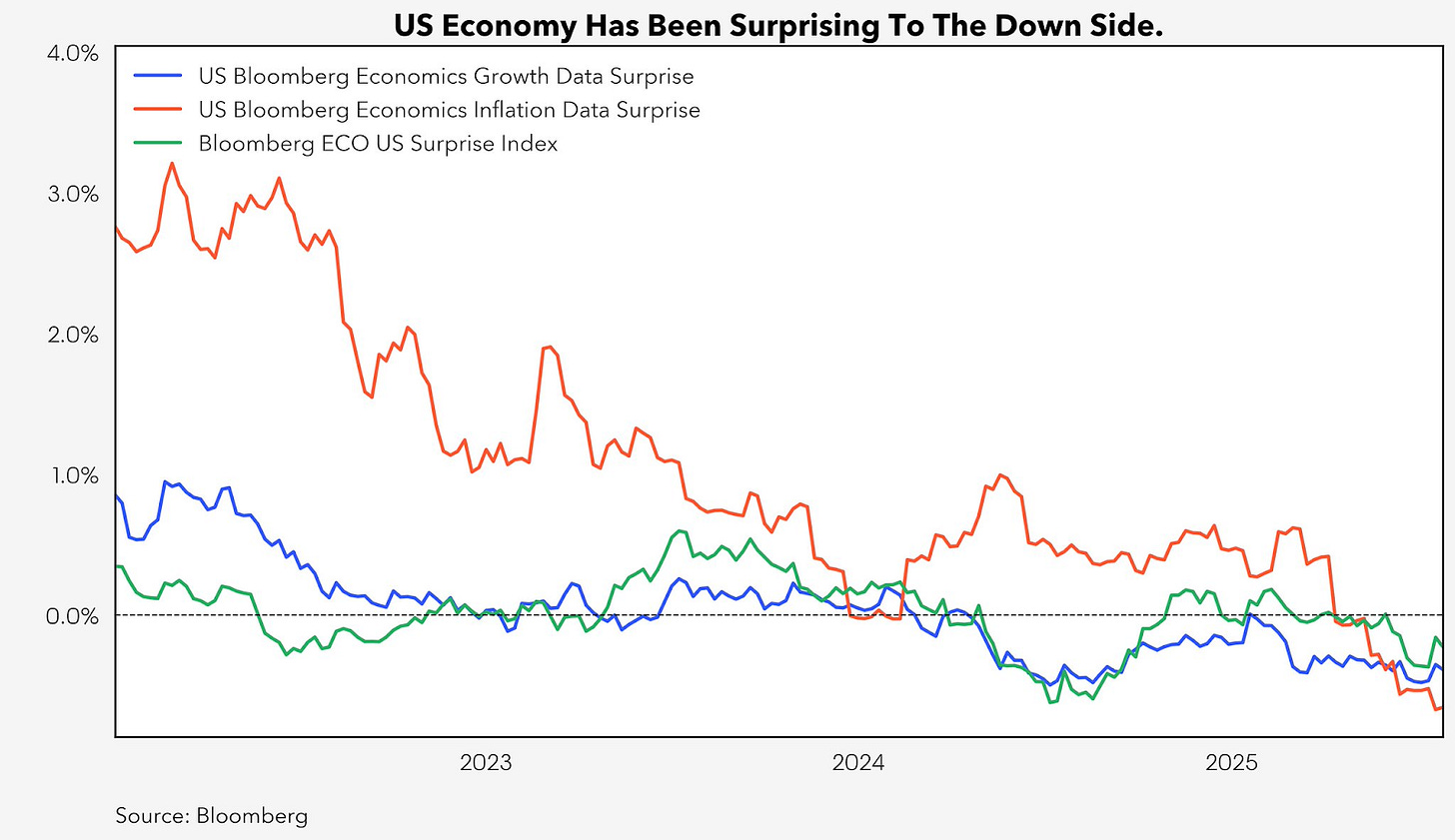

The overall US economy also continues to exhibit signs of gradual slowing, with most data coming in modestly below expectations. The Bloomberg Economic Surprise Indices, which track the cumulative gap between realized data and consensus forecasts, reflect this dynamic clearly. In 2025, both the growth and inflation surprise indices have turned negative, despite persistent market concerns over tariff-related inflation.

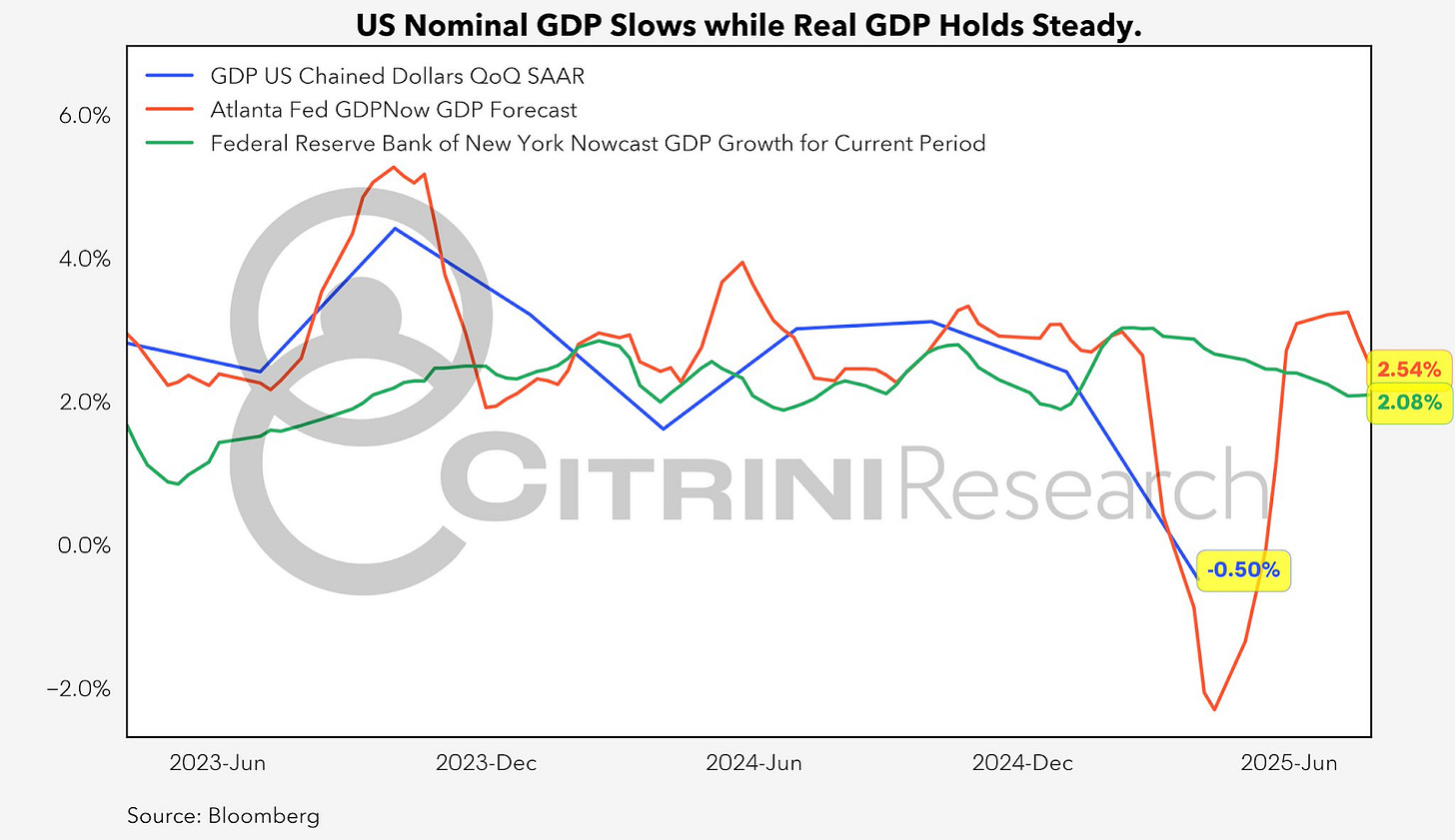

Quarterly GDP reports are typically lagging indicators - not where we’d look first for early signs of slowdown or reacceleration. That said, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model offers a real-time proxy. While imperfect, it has proven directionally reliable, notably capturing the mild contraction in Q1. For Q2, the model points to a rebound toward a stable, trend-like growth rate - neither recessionary nor reaccelerating.

Trade War Resolution

To anticipate tariff policy developments, we’ve relied on a constraint-based framework - analyzing the structural incentives facing key actors, particularly President Trump. This approach has proven useful. For instance, it led us to forecast that major trade partners, especially the U.S. and China, would each pursue incentive-compatible off-ramps rather than escalate. That call has largely played out, reinforcing the value of focusing on political constraints rather than headline rhetoric.

While US-China tensions have rightly taken center stage, we’ve said less about the tariff resolutions involving America’s other major trade partners. The reality is that allies like the EU and Japan were never in a strong position to push back meaningfully in a trade spat with the US. Their negotiating leverage has been structurally weak for two reasons:

They rely heavily on the U.S. defense umbrella in the face of threats from Russia and China.

As net exporters to the U.S. that also compete with one another, they are unable to coordinate effectively as a unified bloc.

In this light, the recent headlines touting “breakthrough” trade deals with Japan and the EU come as little surprise. These agreements represent less a negotiated settlement and more a strategic acquiescence. The administration’s negotiating tactic “apply maximum pressure, create chaos and confusion, relieve maximum pressure” appears to have worked to perfection.

The US - China trade talks could follow the same smooth-sailing trajectory we’ve seen with the EU and Japan. As we noted in previous memos, both DC and Beijing have strong incentives to take their respective off-ramps—and that’s largely what’s been playing out. Just recently, SCMP reported the US-China trade war deadline was extended another 90 days, with both sides agreeing to meet in Stockholm.

While we’re happy to see our prediction come true, we caution against complacency. The US and China remain locked in an irreversible strategic divorce - stabilized only by the mutual leverage they hold over each other’s supply chains. Despite President Trump’s own lack of ideological rigidity, there is broad bipartisan consensus in Washington around the long-term strategic rivalry with China.

Now that the EU and Japan trade deals are largely resolved, the U.S. enters this next phase with added leverage. Both the EU and Japan have their own growing tensions with Beijing, which may further tilt the balance. But this quick succession of “positive” trade headlines may lull investors into misinterpreting a strategic détente as a true rapprochement.

In our last macro memo, we highlighted MP Materials (MP US) and The Metals Company (TMC US) as solid ways to play the US-China decoupling. Since then, both stocks have moved significantly higher. Notably, MP received a major vote of confidence with the DoD becoming a large shareholder and Apple signing on as a key customer. The stock has re-rated sharply upward, validating our thesis. At current levels, we believe much of the upside is priced in, and we recommend taking profit. This “truce” period is likely to be used by both sides to fortify their domestic vulnerabilities. Any temporary thaw and the resulting sell-off of rare earth names may offer new entry points.

Will Tariffs Drive Up Inflation?

As more “trade deals” emerge - “deals” in quotes, as these are so far informal handshake arrangements rather than legally binding agreements - the resolution of the trade war is gradually coming into view. Even while writing this piece, a “framework” for an EU trade deal was announced (15% blanket except for autos).

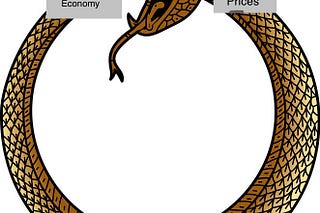

Tariffs should be understood in two key ways. Firstly, a tariff is a tax - a regressive consumption tax that disproportionately affects lower-income households, who spend a larger share of their income on imported goods. Like all taxes, tariffs discourage the activity they target. In this case, that means higher prices on imports, reduced trade volumes, and likely some drag on economic growth. While tariffs may eventually incentivize domestic capital investment, those effects tend to materialize slowly and lag well behind the initial economic friction they cause.

Second, the inflationary impact of tariffs is likely to be modest, finite, and phased in over time. As taxed goods arrive at U.S. ports, the cost increases will pass through gradually -- either through higher end prices or via corporate margin compression. The result is a slow, staggered inflationary effect, not a sudden spike.

We remain firmly of the view that tariffs, on their own, are not meaningfully net inflationary, if at all. Their impact is best understood as a one-time price level adjustment on imported goods, largely transitory and dampened by market competition, pricing strategies, and corporate absorption. And given that the U.S. economy is predominantly service-based, continued disinflation in services should help offset temporary goods inflation.

“The Powell Struggle”: Politics, Policy, and the Path to Rate Cuts

The trajectory of U.S. interest rates is no longer just a function of inflation data or labor market prints, rather, it is increasingly shaped by the political economy surrounding the Federal Reserve. The “Powell Struggle” is our shorthand for this evolving tug-of-war between the Trump administration’s political objectives and the institutional constraints of the central bank.

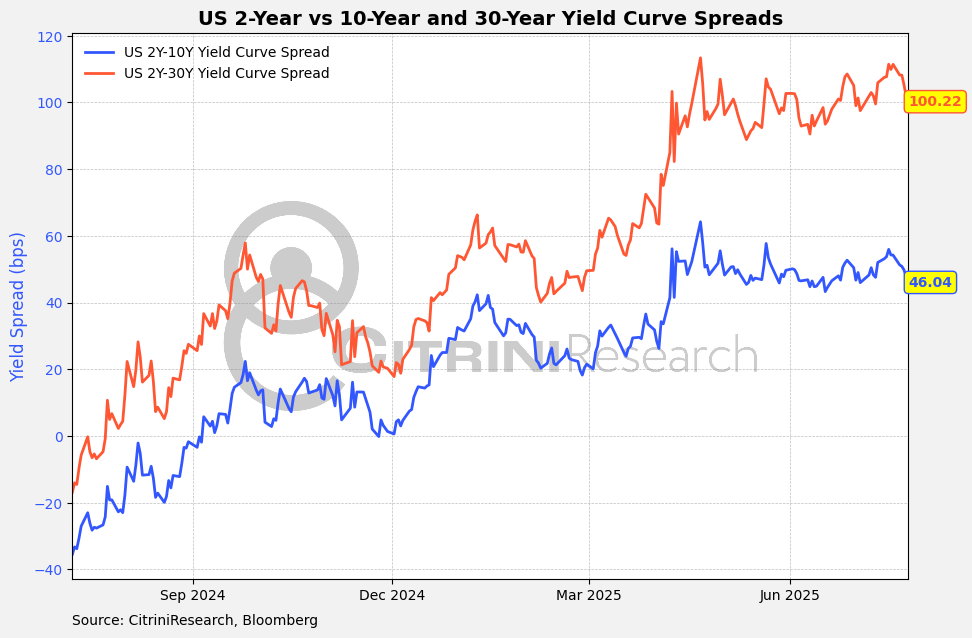

Over the last 6 months, the tension between President Trump and the Fed became increasingly overt, turning the Oval Office into a rate‑cut soap opera. President Trump blamed Chair Powell for keeping mortgages above 6 percent, floated a firing rumor, and name‑checked the 1951 Treasury‑Fed Accord. Markets shrugged: Fed funds stayed pinned, ten‑years barely flinched, 2s10s seems to have fully priced in the “human steepener” of a Trump presidency.

The Political Incentive: Why Rates Matter to Trump

Trump’s drive for lower rates stems from electoral calculus. Housing affordability, credit access, and cost of living rank consistently as the top voter concerns. Lower interest rates - especially mortgage rates - are seen as central to reversing his favorability with key constituencies. [Trump’s recent “mulling” about distributing rebate checks to low income households, which requires Congressional approval hence highly unlikely, reveals his inner dialogue about addressing the cost of living issue.]

Initially, Trump appeared to believe the Fed alone was holding up interest rates across the curve. But that’s not how rates work.

Advisers (think Bessent, Miran) reminded Trump the Fed controls overnight money, not the long end. Confrontation has morphed into coordination:

Tariff Truce: Back‑channel “mini deals” have shown up, which are likely to suppress the tariff-driven goods inflation narrative.

Quiet Fiscal Tread: The headline size of OBBB masks back‑loaded spend.

Regulatory Nudges: Disinflationary tweaks (environmental waivers, biofuel credits) have reinforced the cooling narrative.

We’ve seen 2 year breakeven inflation fell 30bp and the ten‑year term premium fell some 20 bp from May highs, giving the Fed cover to talk cuts.

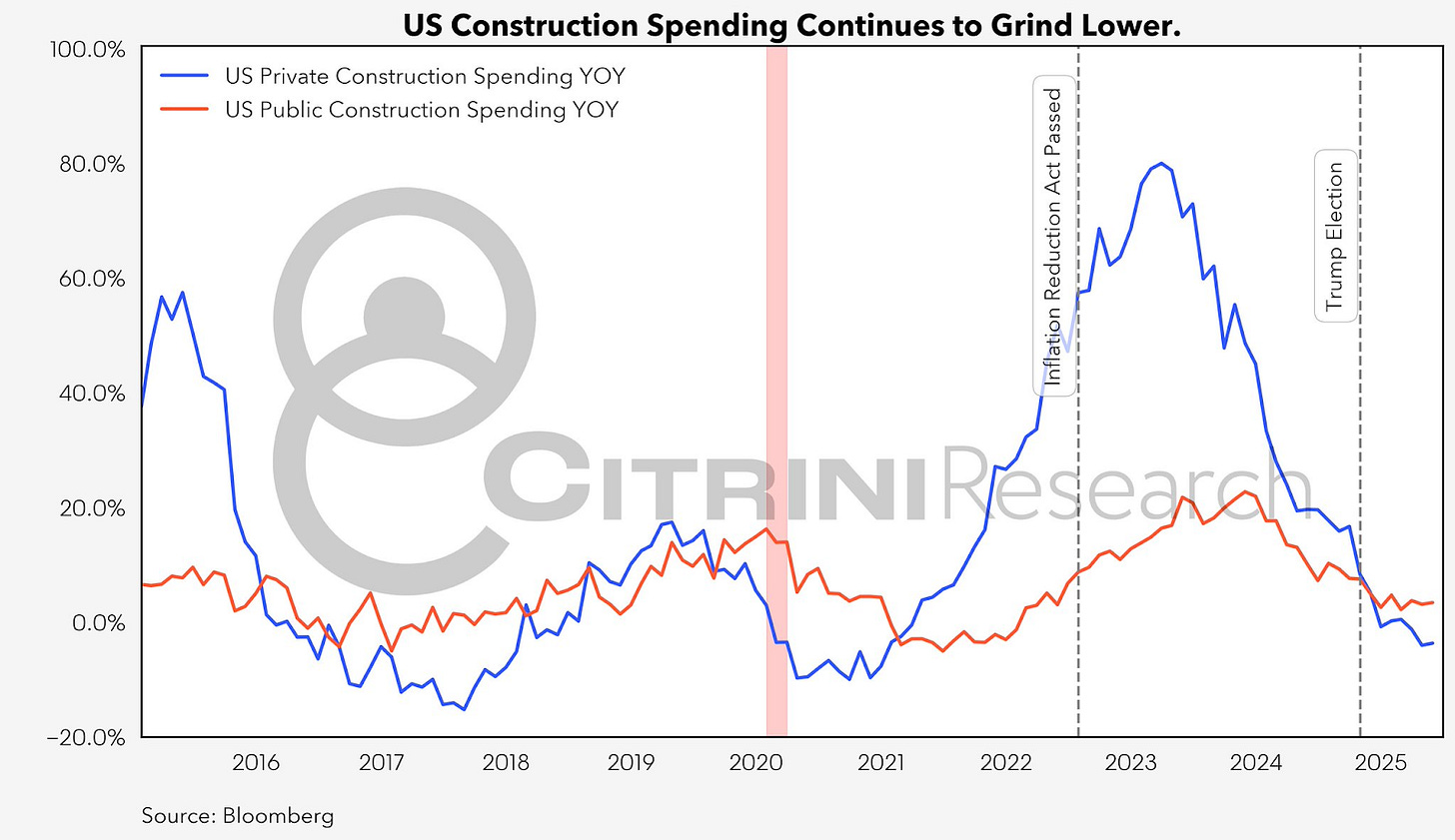

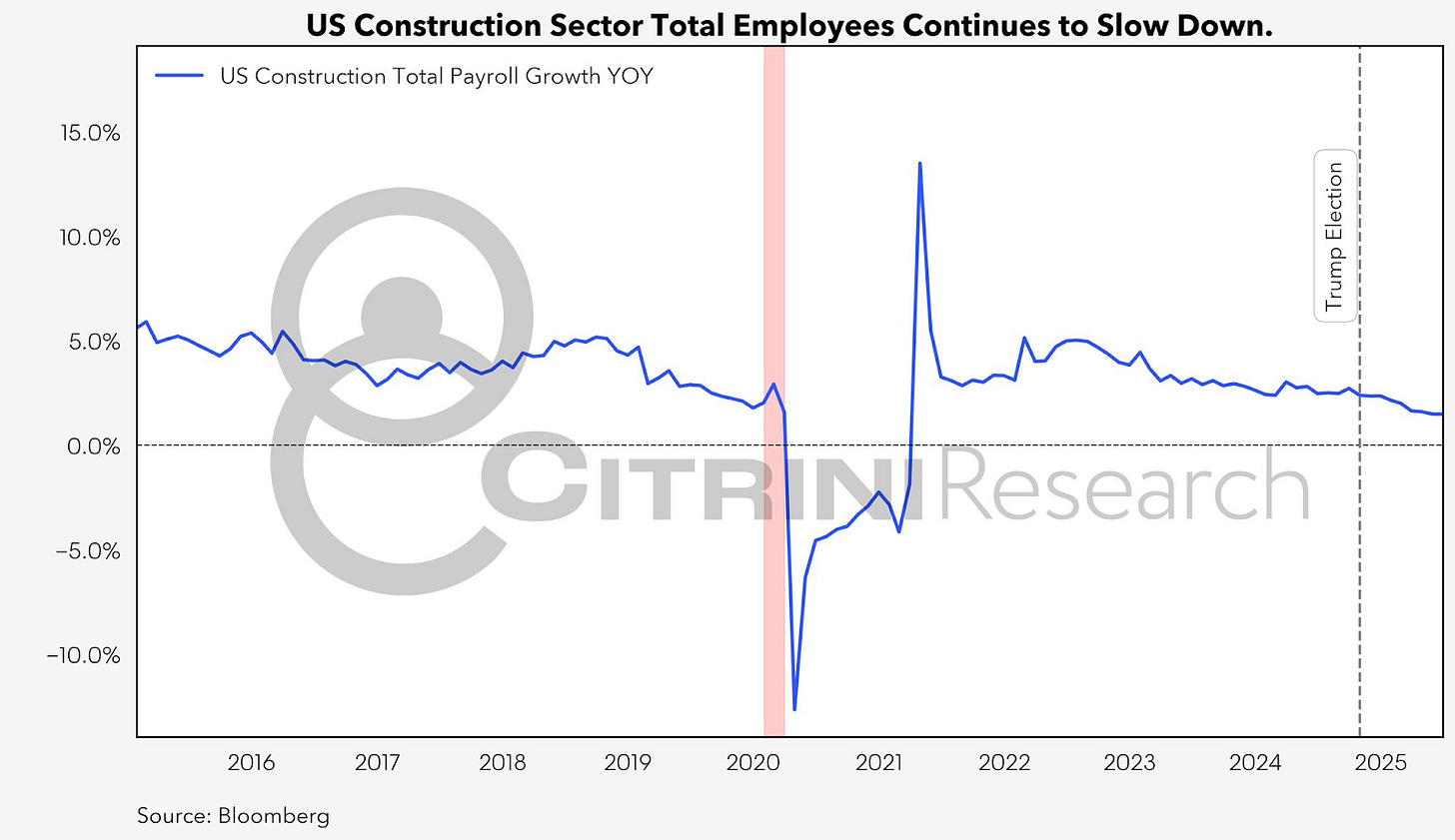

Finally, worries that a domestic‑capex boom might reignite inflation look premature. Both private and public construction‑spending growth continue to glide lower, and construction payroll growth has cooled from ~5 % YoY in 2022 to barely 1 % today. Even concerns over labor shortages tied to mass‑deportation rhetoric have not reversed that downtrend. A genuine re‑acceleration would almost certainly require materially lower mortgage rates - something that can only follow once the Fed opens the easing door.

Inside the Fed: Building the Case for Cuts

On the other side of the table, dovish FOMC members like Governor Chris Waller have made a coherent case for preemptive easing, arguing that inflation risks have receded and policy should stay forward-looking. It’s likely that internal persuasion efforts are underway to soften resistance among more hawkish members. Powell, ever sensitive to institutional credibility, may be positioning himself for a “data-dependent” pivot.

Waller: “Tariffs are one-off increases in the price level and do not cause inflation beyond a temporary surge. […] Besides tariffs, I don't expect an undesirable, sustained increase in inflation from other forces.”

However, we could also see the scenario where Waller’s adamant dovishness and potential dissent in coming FOMC meetings is a mechanism by which the Fed “circles the wagons” rather than opens up continued dovishness. Essentially, this looks like a recognition by the existing FOMC members that there could be a threat to central bank independence with the next Fed Chair. Positioning Waller as a dovish dissenter might help ensure there is a viable option for Trump within the current FOMC.

We expect that, barring a major inflation surprise, Powell will open the door to a September rate cut either at the July FOMC meeting or in his Jackson Hole address in August. Markets are mostly priced for this, with 1.75 cuts priced in by the end of the year.

The Powell Struggle had its likely end marked by the “everyone laugh for the cameras” moment we saw with Trump’s visit to the Fed - likely coordinated/orchestrated by Bessent. Thus, this struggle is no longer about whether the Fed will yield to political pressure but about whether political actors can construct a macro narrative compelling enough for the Fed to act on its own accord. The dovish convergence we’re witnessing between quieter fiscal maneuvering and softening Fed language opens questions to whether the most aggressive cutting of this cycle comes from Powell or from his successor. We believe that the most likely outcome is the latter, with Powell sticking to the dot plot while continuing dovish commentary at FOMC pressers. In STIR, we see more opportunity in playing the spread between rate cuts out to the end of Powell’s term vs the first year of his successor’s term than in simply playing rate cuts in whites and reds.

Above all, we expect long-term interest rates - both government and private - to trend gradually lower as this alignment takes hold. The fact of the matter is that it shouldn’t matter for 10 year+ yields whether it’s Powell or his successor that begins cutting rates. As long as inflation remains relatively controlled and Trump’s threats have less bite, we believe bond yields should stay capped.

Late Summer Correction or Dotcom Déjà Vu?

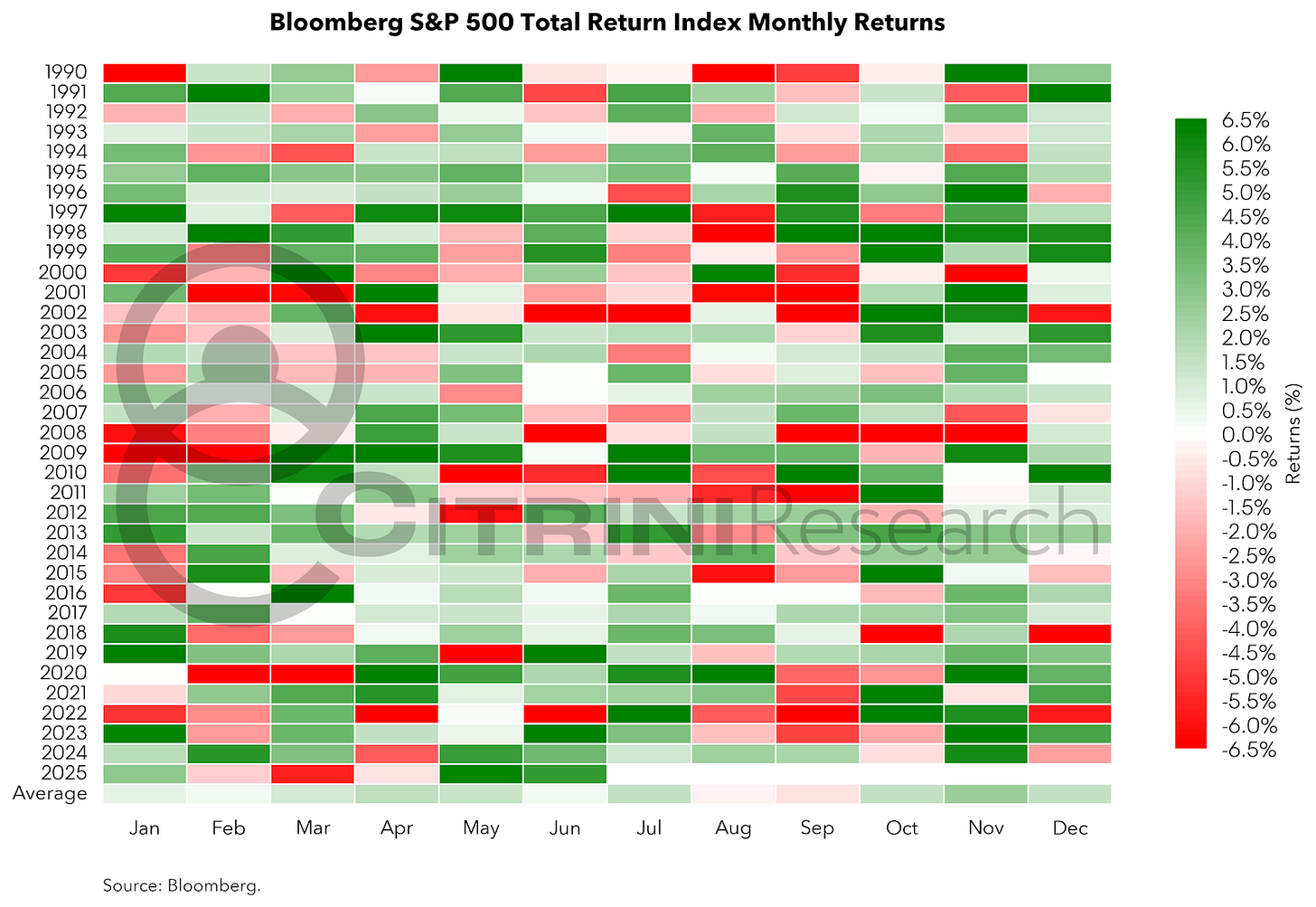

Rich pricing and investor complacency (e.g., VIX under 15) raise the prospect of a market pullback. Also, August and September tend to be seasonally weak as the below heat map shows.

Dotcom Déjà Vu?

The recent parallels to 1998 are striking. The depth and duration of the 1998 correction match almost exactly to the 2025 correction – as does the recovery period to new all-time highs.

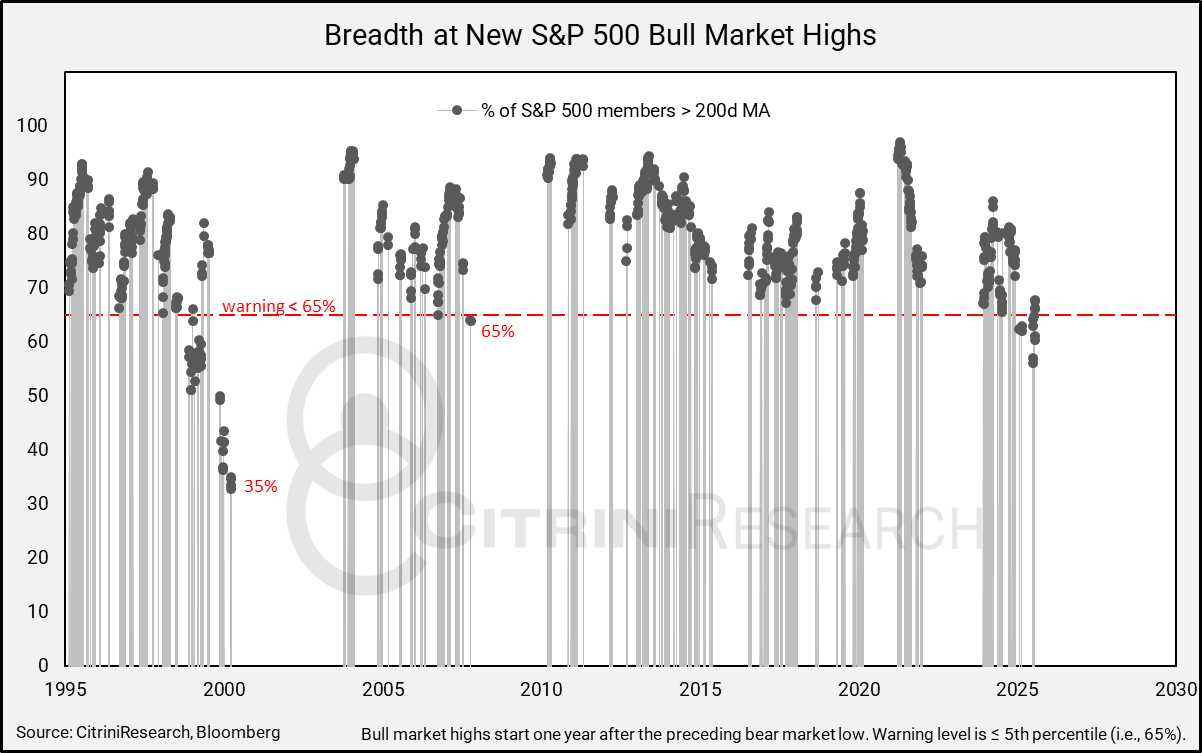

Market breadth, as measured by percent of S&P 500 members above their respective 200-day MAs when the market is making new highs, has recently been at the weakest levels since late 1998. If the market continues to march higher on weak and declining breadth, that may mark the beginning of the “bubble phase” of this secular bull market.

At the market top in March 2000, only 35% of S&P 500 member companies were above their respective 200-day moving averages.

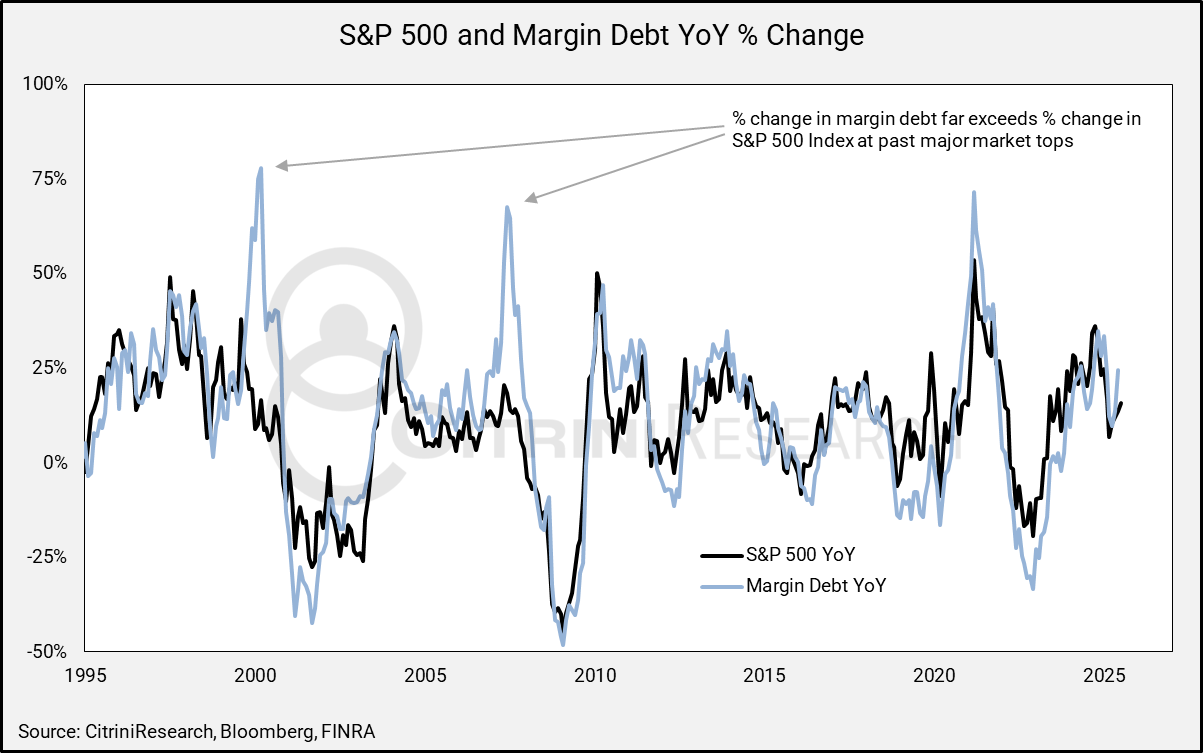

Still, the market has a potential wall-of-worry left to climb, judging by the high readings on the US Economic Uncertainty Index. Furthermore, margin debt build-up relative to the market remains fairly benign.

On the chart above, the rise in margin debt in early 2000 and mid 2007 stands out relative to the rise in the market. For example, margin debt grew more than 75% from early 1999 to early 2000, while the S&P advanced less than 25%. The key point is that during the final stages of a bull market - one that leads up to a major market top - margin debt tends to grow rapidly (and far faster than the market’s rise) as investors become more confident and therefore more leveraged, indicative of irrational exuberance.

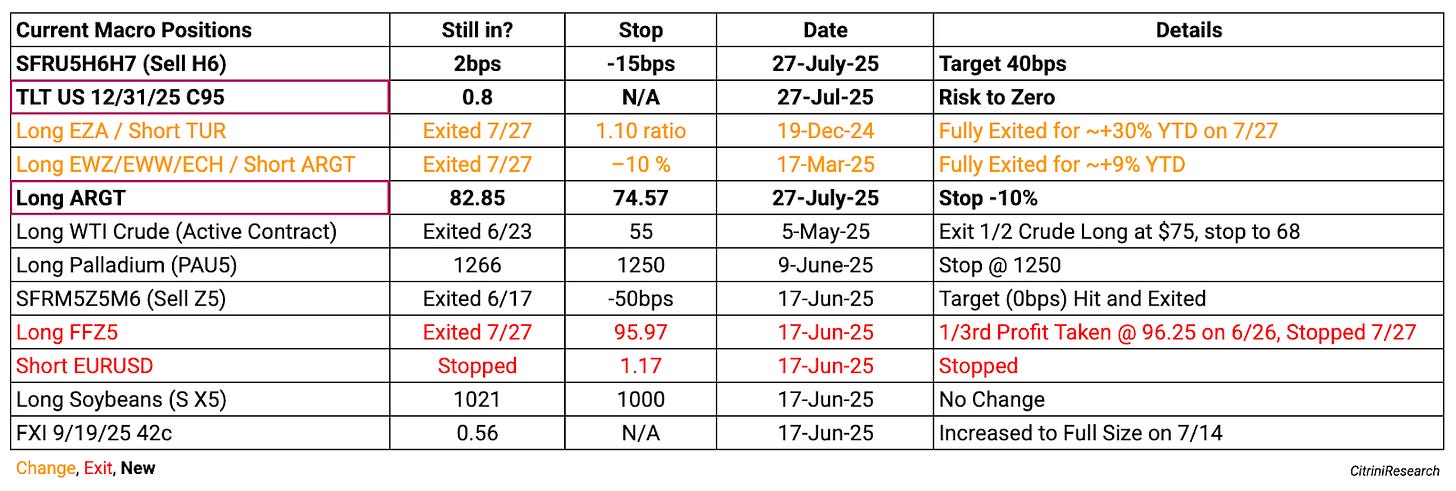

Current Macro Positioning Changes

We make the following adjustments to our macro positioning.

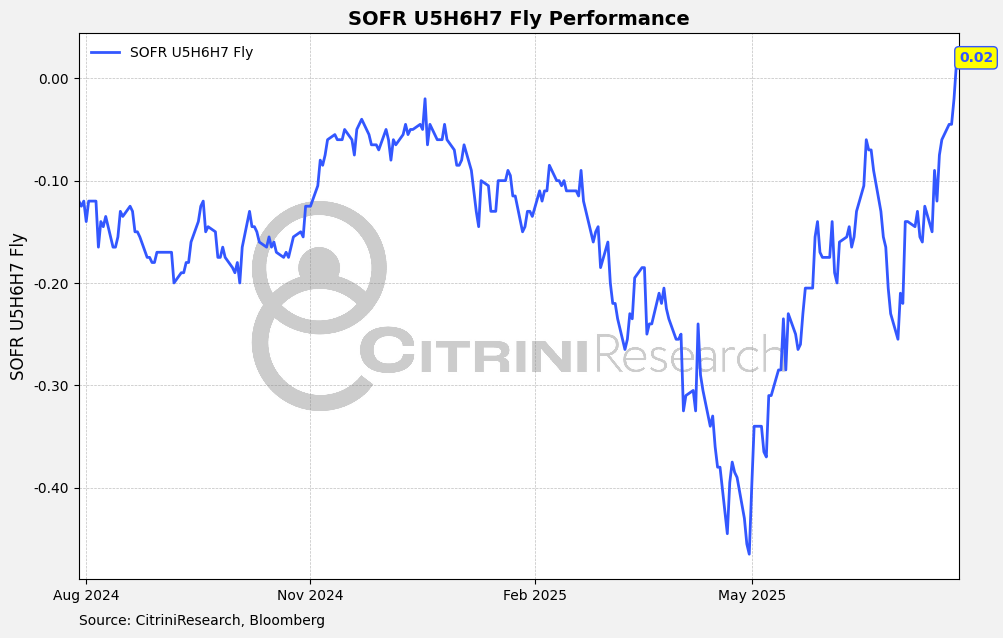

New Position: Sell H6 on SOFR U5H6H7 Fly

In our last memo, we stated “Our call: we believe that Powell opens the window to a resumption of the cutting cycle in July.”

While we still think this is the case, the market is currently pricing in roughly the same amount of cuts between September 2025 and March 2025 as are priced into March 2026 to March 2027. While we agree with Waller that rate cuts should come sooner rather than later, we think it’s difficult to underwrite that given the U.S. economy is not giving clear signs of rates being too restrictive.

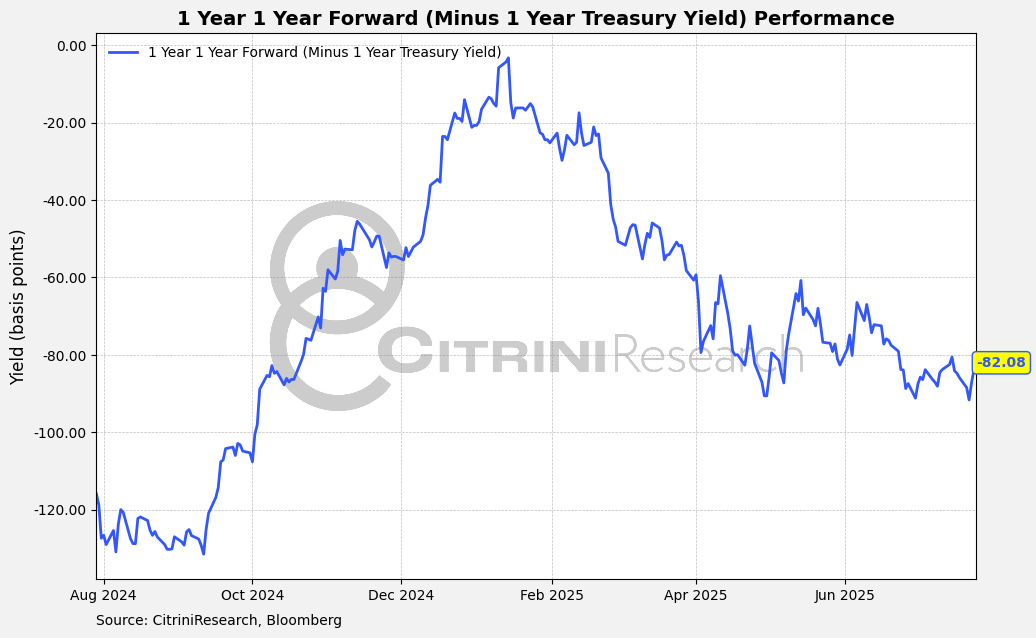

Right now, the 1 Year Yield 1 Year forward is roughly 82bps lower.

We play more cuts being priced into the period of March 2026-27 than September 2026-March 2026 (long SFRU5H6 Steepener + SFRU6U7 flattener). How do we lose? If there is some tail risk presented to the economy that results in significant rate cuts being pulled forward to accomplish a policy rate significantly lower than the ~3.25% priced in for March of next year (for example, if conditions require the Fed cutting rapidly to 2% and then the expectation was that the Trump appointee would keep rates there for a year, we’d end up doing quite poorly on this trade).

How do we win? This might be a bit basic, but like we said at the top of the piece - the macro trading regime seems to have shifted a bit away from fading extremes and towards leaning into the obvious. So, we win if the FOMC sticks to the dot plot and then the next Fed chair is anticipated to get more aggressive (even if Powell does cut out to the end of the term), we believe this spread will begin pricing in more cuts further out than nearer.

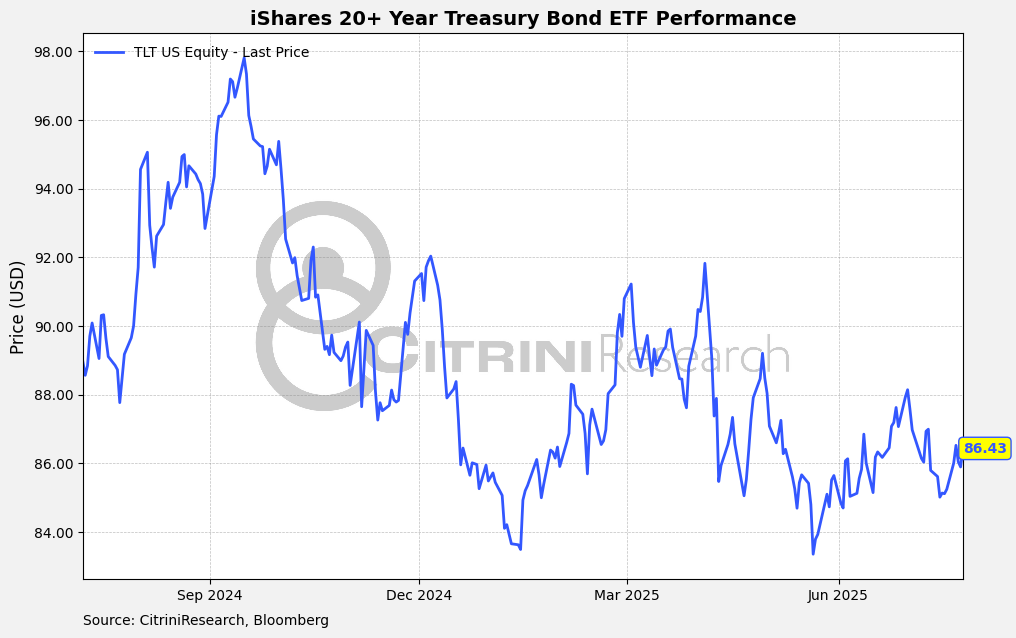

New Position: Long TLT December 2025 95 Calls

The long end has been a bit confusing, but I’m a big believer in taking signals from failed plays and price action. Recently, we had a headline that was quickly addressed by the Trump administration regarding the firing of Jerome Powell. Based on the way the market has reacted to Trump this year, I felt it would be a good idea to put on the steepener - anticipating that even if Trump didn’t actually fire Powell, the fact that he can’t seem to help himself in continuing to talk about it would result in more selling of the long end.

I was quite surprised to see that this ended up being a “sell the news” event. We quickly stopped out of our 2s10s steepener, which I reflected on a bit. If we are in the kind of environment where no “Powell firing threat premium” is getting priced into the yield curve, then why aren’t rates on the long end coming down in anticipation of Trump’s next Fed Chair playing ball on rates?

The fact of the matter is that regardless of whether it’s Powell or his successor that delivers the bulk of the rate cuts, anticipating those cuts in the next couple years should naturally result in lower rates on the long end when term premium is already around/above the historic mean. Like we said at the beginning of this piece, the U.S. economy is at a crossroads. While I believe the tailwinds being experienced are more than enough to continue getting us there, I also recognize I could easily be proven wrong (and that we’re entering a seasonally weak period for equities that could result in bonds getting a second consideration by investors).

I think this is a reasonable spot to own some upside optionality in TLT. I would rather own calls that seem fairly priced than the underlying, as there is certainly the chance of another April type reaction (to what, I don’t know, but the market’s reactions to Trump’s unpredictability are unpredictable themselves). Anything that puts the assumption of us being in a 4-4.5% nominal growth would result in a rapid repricing of the long end, and that should sufficiently hedge our STIR play and allow us to really size into the SOFR fly above (which has its most bearish outcome in the scenario where a next 12 months return to neutral is priced in), with the potential to even work alongside. I believe this is a positive EV hedge (famous last words…).

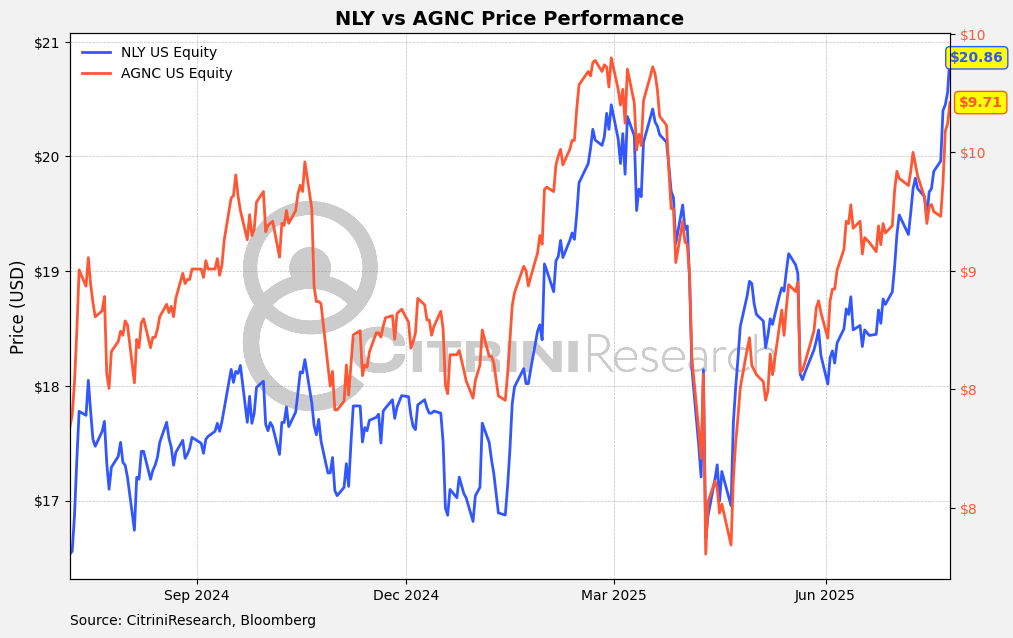

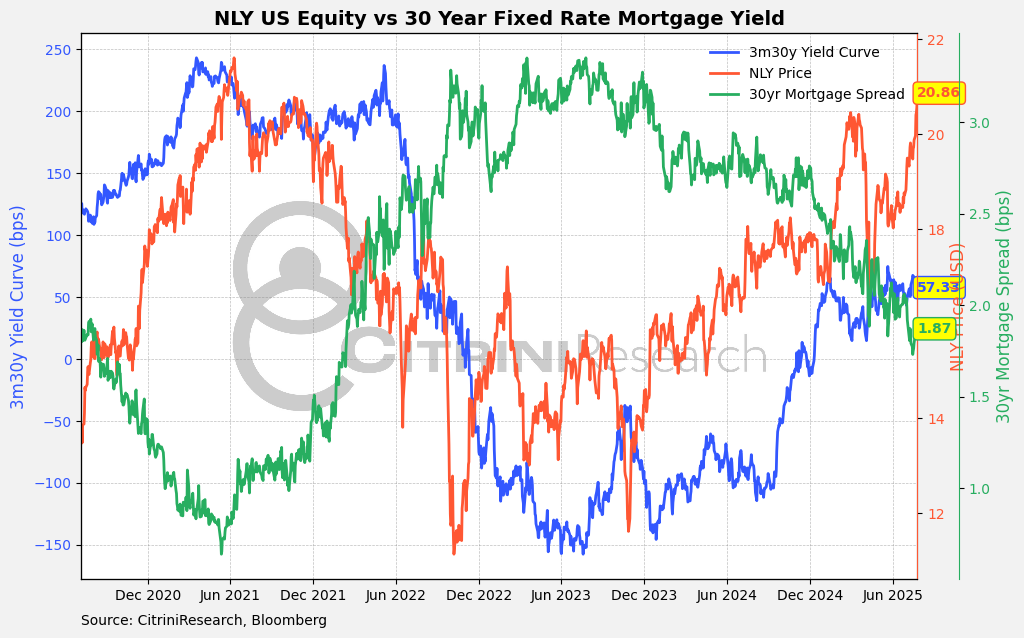

On our Watchlist: Agency MBS REITS

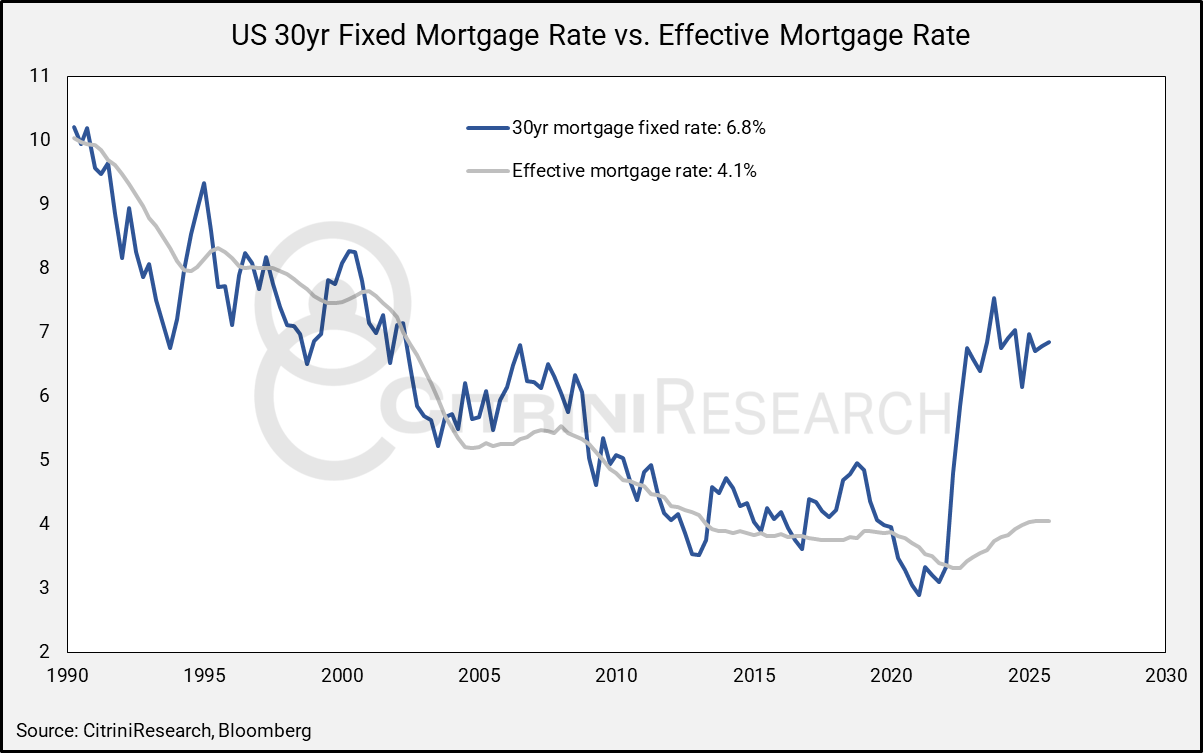

Agency MBS REITs (NLY US and AGNC US) also have broken out - recovering their post-Liberation day drawdowns. This is mostly a function of spreads: Repo and FHLB advance rates, the lifeblood of agency REIT leverage, move with the front end. With Fed cuts having been priced in and the long end refusing to budge, book yields on legacy 3‑4‑percent mortgage pools have held steady near 5.4 percent, as the liability leg is set to re‑price lower, lifting net interest margins (NIM). Annaly’s GAAP NIM popped to 1.04 percent in Q2, up 17 bps year‑on‑year, with the more telling “economic” NIM (ex‑PAA) at 1.71 percent. Additionally, prepayment speeds have run significantly below trend. At 6.8% for a 30yr mortgage homeowners are deeply out‑of‑the‑money (in the context of a 4.1% effective mortgage rate). The MBS Bank/real-money buyer base has also come back after being below historic trends for a few years.

If we were to get a parallel shift much lower, or a bull-flattener, these likely would underperform. AGNC’s own shock table from 2023 shows a 50 bp parallel decline trims tangible book value 3.8 percent and a 75 bp move lops off seven percent . From here, the most likely scenario for continued outperformance of the mREITs versus just pure duration would be a mild bull steepener.

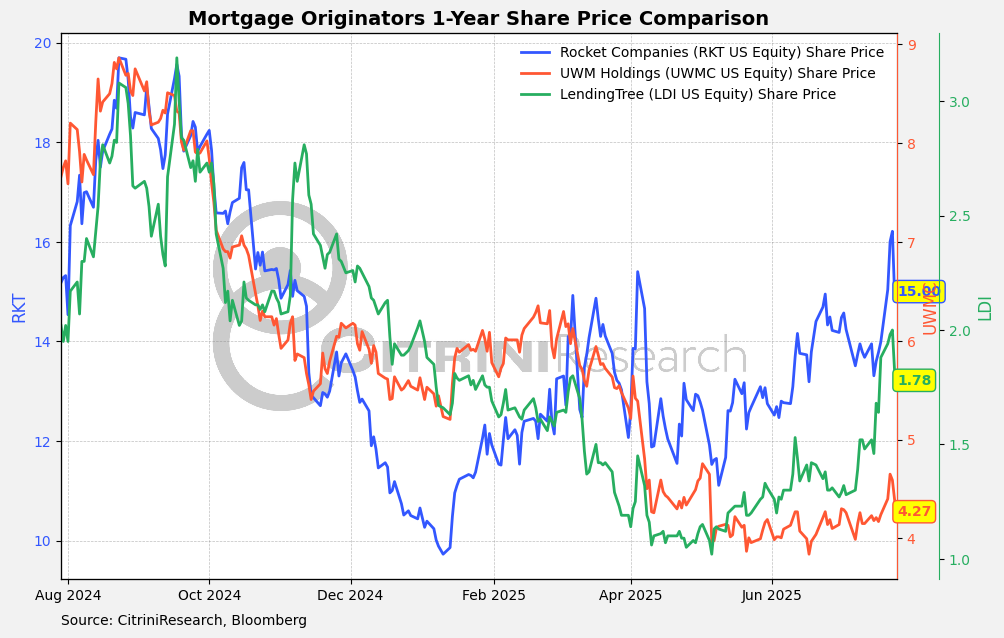

On our Watchlist: Mortgage Originators

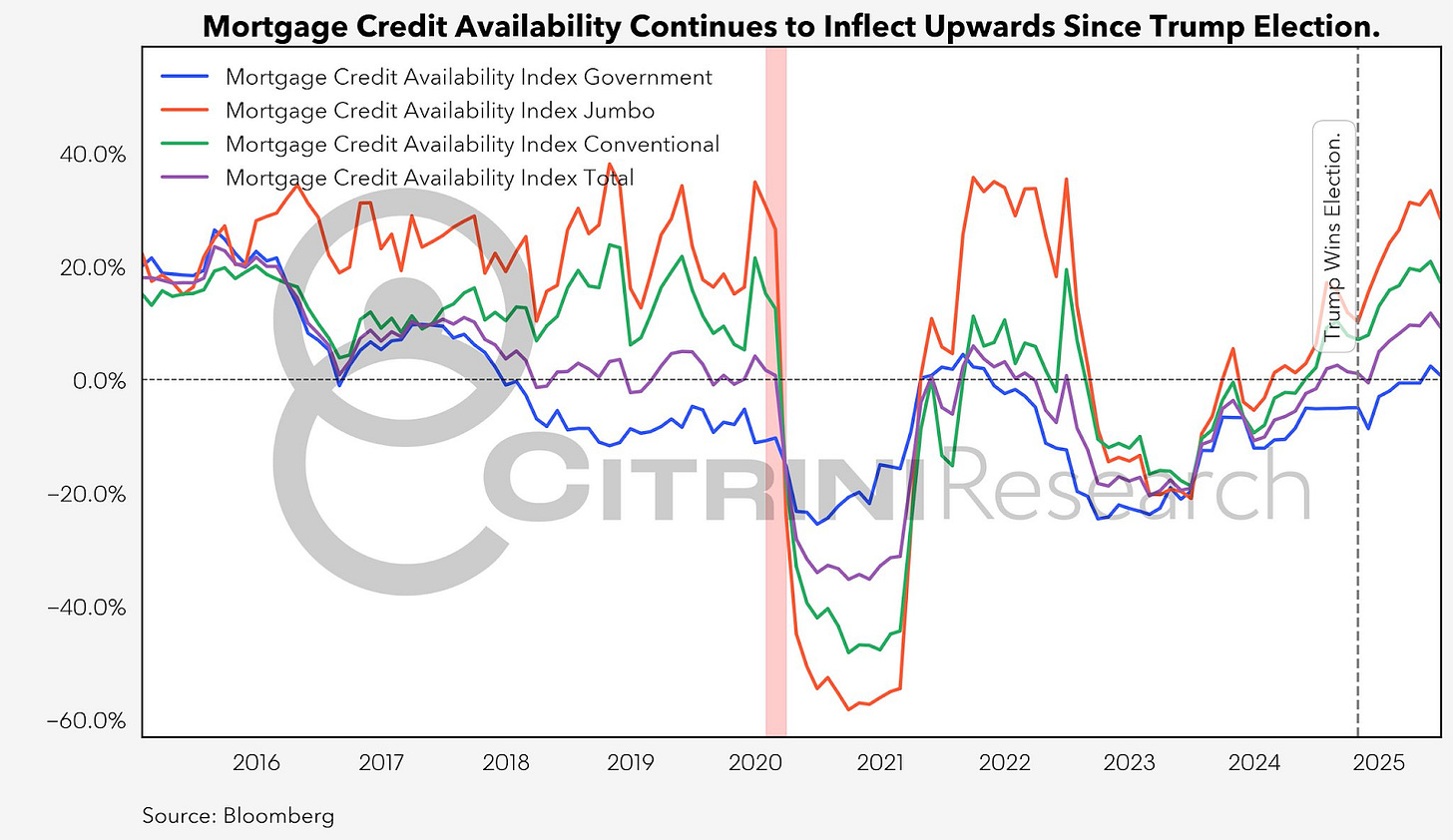

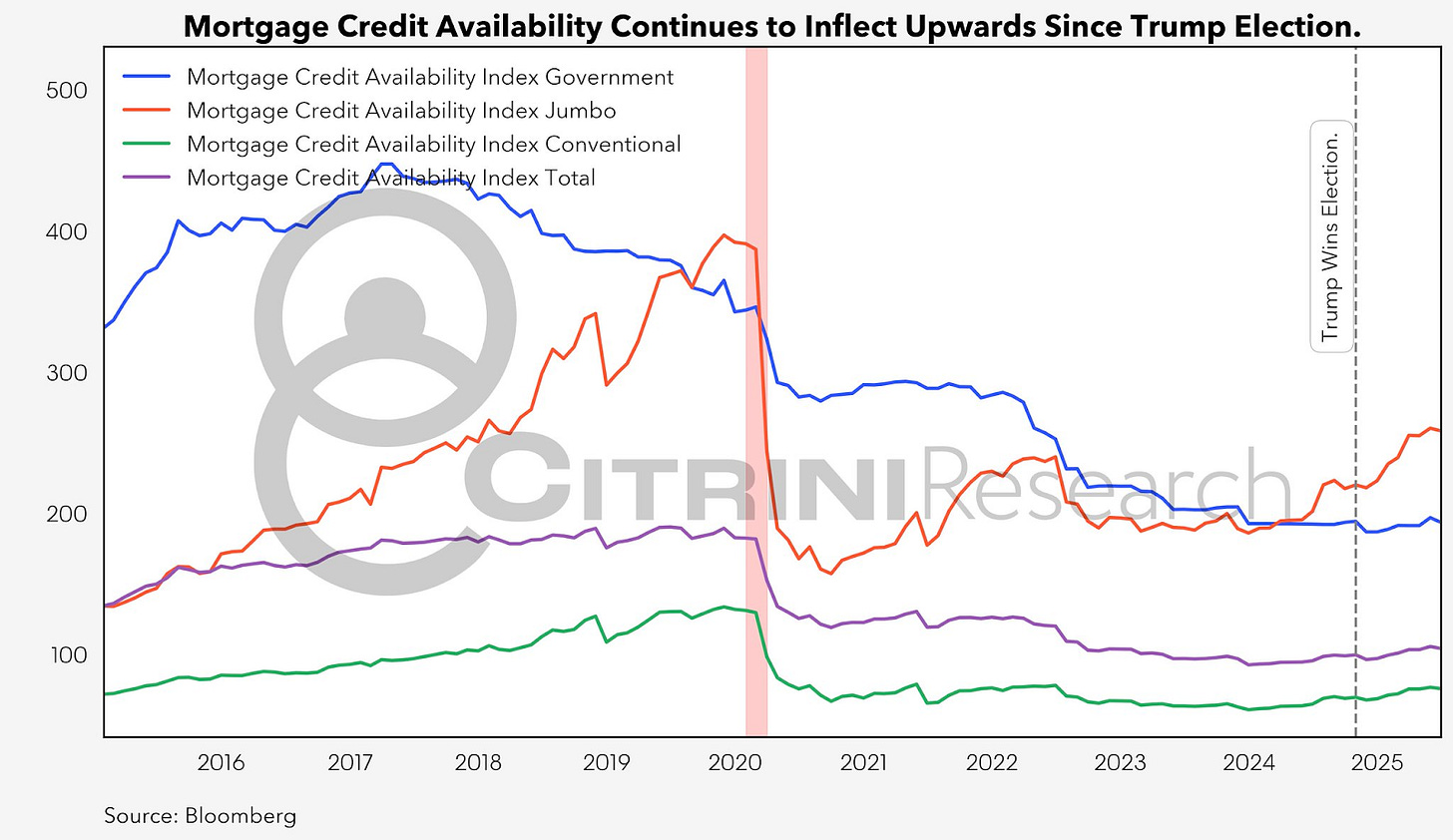

There’s also been some buzz about RKT and mortgage originators. However, a rocket can only launch when it has the velocity to escape gravity. On the origination side (RKT/UWMC), we need either a 75‑100 bp rally in mortgage rates or a decisive loosening in inventory and credit. Anything short keeps demand choppy and purchase‑heavy. We’d like to see a stronger trend that suggests a direction of travel that will bring the Mortgage Credit Availability Index (MCAI) above 110 or mortgage rates below 6% to play these on a macro thesis.

Existing Position: Short EURUSD (Stopped)

EURUSD has been the most frustrating of the positions from our last memo. I still, strongly, see an environment where the Dollar could stage a rebound / short squeeze but it’s clear that the timing is more difficult than expected. I’m holding off for now, but I think it’s incredibly risky to continue being long EURUSD here and I’ll be looking for confirmation to get back in (probably via put options so it can be a “set it and forget it” play).

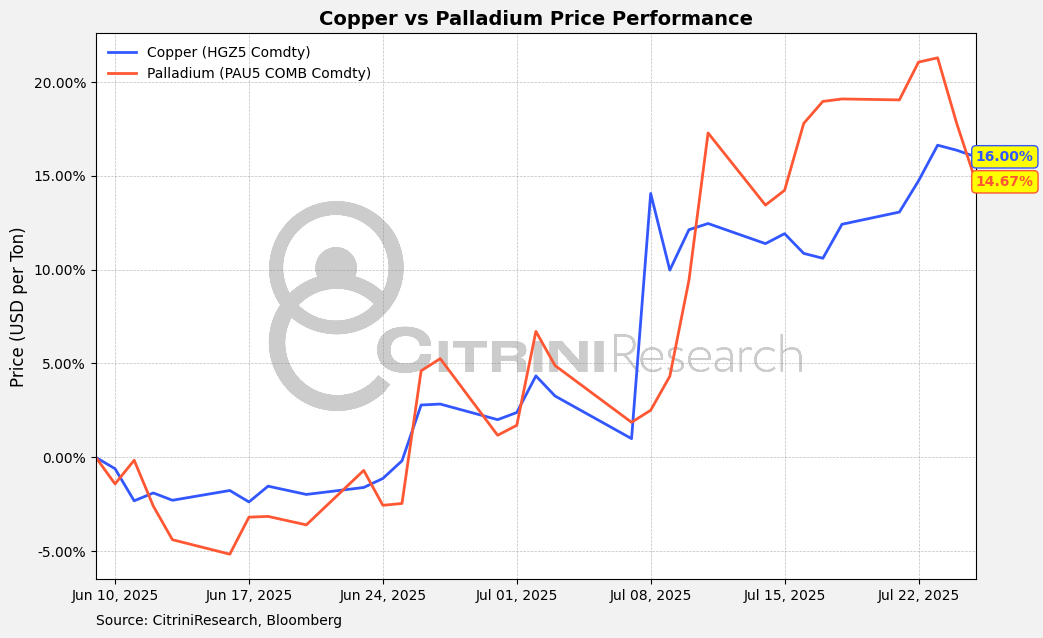

Existing Position: Long Palladium

In our last macro memo, we stated:

“Consistent with our view on the auto cycle and the economy, we have initiated a long on palladium as of June 9th, replacing our long on HGZ5”

This has performed well and we’re taking a pure price action perspective - we sold out of half of our position above $1300 and have been waiting to see if price is able to be resilient above that. Friday showed some weakness that we’ll be selling into if it continued (stop at $1250 hourly close).

Benchmarking to the copper long we exited to favor Palladium, we ended up outperforming when we first monetized half, but have recently dipped below.

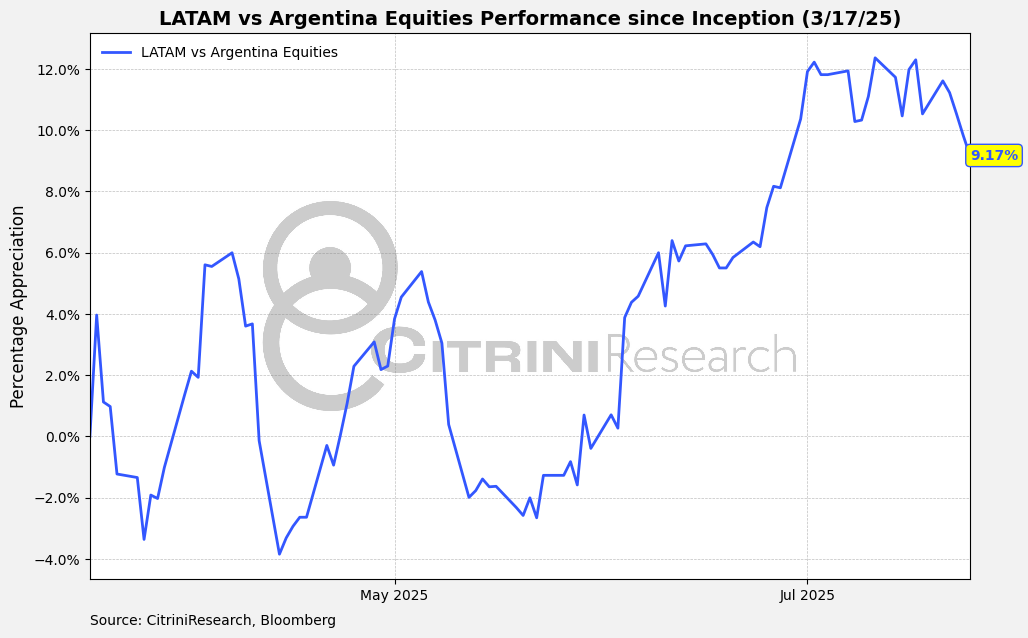

Exiting our Long LatAm vs. Argentina, Flipping Long

We have gotten what we wanted out of the Long EWW+EWZ+ECH vs. Short ARGT trade - since we put it on in March these 3 have notched about 10% outperformance. While Chile, Brazil, and Mexico benefited from relative stability, nearshoring trends, and orthodox economic policies, Argentina lagged due to the initial pain of aggressive fiscal cuts and a sharp currency devaluation aimed at tackling hyperinflation. We’re turning tactically bullish, anticipating a strong performance from Milei’s party in the mid-terms.

Re the relatively tame amount of margin debt as indicated in the chart, could this simply be a matter of investors using more options to establish leveraged positions vs utilizing cash and increasing margin debt? Sure, there would be a cash margin requirement for holding the options, but it should have less of an effect on reported margin *debt* unless investors really go off the deep end on the risk curve (if their platforms would even allow this).

Excellent analysis. Only thing I would add is that while the naming of a new Fed Chair will be important and influential, the Fed is a slow-moving institution and a change in direction or the pace of lowering rates might by slower than most expect under a new chair.

The FOMC has seven governors and 12 Fed presidents around the table—the presidents rotate in voting but their views are taken seriously by a consensus-run committee. If a new chair is viewed as a political partisan who is interested in carrying the president’s water as opposed to blending in and leading the committee’s independent views, there will be a negative reaction by the committee and his ability to lead will be impaired.

Trump’s heavy handed criticism of Powell is going to make it more difficult for a new chair to lead effectively if he’s an outsider from the Trump team. This is one reason why the savviest choice to lead the Fed would be Waller.