Abstract 摘要

Background 背景

Interindividual variation characterizes the relief experienced by constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C) patients following linaclotide treatment. Complex bidirectional interactions occur between the gut microbiota and various clinical drugs. To date, no established evidence has elucidated the interactions between the gut microbiota and linaclotide. We aimed to explore the impact of linaclotide on the gut microbiota and identify critical bacterial genera that might participate in linaclotide efficacy.

个体差异特征化了利那洛肽治疗便秘型肠易激综合征(IBS-C)患者后的缓解情况。肠道菌群与多种临床药物之间存在复杂的双向相互作用。迄今为止,尚无确凿证据阐明肠道菌群与利那洛肽之间的相互作用。我们旨在探索利那洛肽对肠道菌群的影响,并识别可能参与利那洛肽疗效的关键细菌属。

Methods 方法

IBS-C patients were administered a daily linaclotide dose of 290 µg over six weeks, and their symptoms were then recorded during a four-week posttreatment observational period. Pre- and posttreatment fecal samples were collected for 16S rRNA sequencing to assess alterations in the gut microbiota composition. Additionally, targeted metabolomics analysis was performed for the measurement of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) concentrations.

IBS-C 患者接受每日 290 µg 剂量的利那洛肽治疗六周,然后在四周的术后观察期记录其症状。治疗前后的粪便样本采集用于 16S rRNA 测序,以评估肠道菌群组成的改变。此外,还进行了靶向代谢组学分析,以测量短链脂肪酸(SCFA)的浓度。

Results 结果

Approximately 43.3% of patients met the FDA responder endpoint after taking linaclotide for 6 weeks, and 85% of patients reported some relief from abdominal pain and constipation. Linaclotide considerably modified the gut microbiome and SCFA metabolism. Notably, the higher efficacy of linaclotide was associated with enrichment of the Blautia genus, and the abundance of Blautia after linaclotide treatment was higher than that in healthy volunteers. Intriguingly, a positive correlation was found for the Blautia abundance and SCFA concentrations with improvements in clinical symptoms among IBS-C patients.

大约 43.3%的患者在服用利那洛肽 6 周后达到了 FDA 的应答终点,85%的患者报告了腹部疼痛和便秘的缓解。利那洛肽显著改变了肠道菌群和短链脂肪酸代谢。值得注意的是,利那洛肽的高效性与布劳蒂亚属的富集相关,利那洛肽治疗后布劳蒂亚属的丰度高于健康志愿者。有趣的是,研究发现布劳蒂亚属的丰度和短链脂肪酸浓度与 IBS-C 患者临床症状改善呈正相关。

Conclusion 结论

The gut microbiota, especially the genus Blautia, may serve as a significant predictive microbe for symptom relief in IBS-C patients receiving linaclotide treatment.

肠道菌群,尤其是布劳蒂亚属,可能成为利那洛肽治疗 IBS-C 患者症状缓解的重要预测微生物。

Trial registration: This trial was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (Chictr.org.cn, ChiCTR1900027934).

试验注册:该试验在中国临床试验注册中心(Chictr.org.cn,ChiCTR1900027934)注册。

Supplementary Information

补充信息

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-024-04898-1.

网络版包含可在 10.1186/s12967-024-04898-1 获取的补充材料。

Keywords: IBS-C, Linaclotide, Gut microbiome, Blautia, SCFAs

关键词:IBS-C,利那洛肽,肠道微生物组,布劳蒂亚,短链脂肪酸

Background 背景

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a pervasive, symptom-driven chronic disorder marked by abdominal discomfort and irregular bowel movements [1] that affects an estimated 11.2% of the global population [1, 2]. Approximately one-third of these patients are diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation(IBS-C), a subtype of IBS. The therapeutic objectives primarily focus on alleviating symptoms, improving the patients’ quality of life, and reinstating their normal social functioning rather than eradicating the disease [3, 4]. Several guidelines and consensus statements have recommended the use of antidepressants, laxatives, prokinetics, and probiotics for the treatment of IBS-C patients. Due to an improved understanding of its pathogenesis, numerous therapeutic agents have been developed, and certain drugs have been removed from the front-line treatment strategies [5, 6]. Given the limitations of conventional treatments, there is mounting evidence highlighting the effectiveness of secretory drugs. These new drugs, which target chloride ion channels, have a clear mechanism of action [7, 8], and an example is the guanylate cyclase C agonist linaclotide [9, 10]. Linaclotide not only mitigates constipation symptoms but also ameliorates global symptoms such as abdominal discomfort, pain, and bloating [11–13]. This drug has been endorsed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the American College of Gastroenterology for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) and IBS-C in adults [3, 14].

肠易激综合征(IBS)是一种普遍存在的、以症状为驱动的慢性疾病,其特征为腹部不适和排便不规则[ 1 ],据估计影响全球人口的 11.2%[ 1 , 2 ]。其中约三分之一的患者被诊断为肠易激综合征伴便秘(IBS-C),这是 IBS 的一种亚型。治疗目标主要集中于缓解症状、改善患者生活质量以及恢复其正常社会功能,而非根治疾病[ 3 , 4 ]。多项指南和共识建议使用抗抑郁药、泻药、促动力药和益生菌来治疗 IBS-C 患者。由于对其发病机制的深入理解,已开发出多种治疗药物,某些药物已从一线治疗策略中移除[ 5 , 6 ]。鉴于传统治疗的局限性,越来越多的证据突出了分泌性药物的疗效。 这些靶向氯离子通道的新药具有明确的药理作用机制[ 7 , 8 ],例如环鸟苷酸环化酶 C 激动剂利那洛肽[ 9 , 10 ]。利那洛肽不仅缓解便秘症状,还能改善腹部不适、疼痛和腹胀等全身症状[ 11 – 13 ]。该药物已获得美国食品药品监督管理局(FDA)和美国胃肠病学学会的批准,用于治疗成人慢性特发性便秘(CIC)和肠易激综合征便秘型(IBS-C)[ 3 , 14 ]。

However, the efficacy of linaclotide treatment has been shown to exhibit significant interindividual variation [15]. A 2018 phase III trial in China revealed that approximately 40% of patients did not respond to linaclotide treatment, potentially due to the multifactorial etiology of IBS-C [16]. To date, the causes of IBS-C have not been fully elucidated, and previous research has focused on alterations in the intestinal flora that are intimately connected with IBS-C [17]. Studies have suggested that the gut microbiota influences not only the onset of IBS-C but also the effectiveness of disease treatment, including the chemotherapy sensitivity in colon cancer patients [18], the impact of metformin on diabetes [19], and the efficacy of rifaximin in treating IBS-D [20]. Through animal experiments, a Japanese study confirmed that linaclotide can enhance the intestinal milieu in patients with renal insufficiency [21]. However, whether linaclotide can ameliorate gut microflora dysbiosis and whether the intestinal flora is correlated with symptom relief in linaclotide-treated IBS-C patients remains to be established.

然而,利那洛肽治疗的疗效显示出显著的个体差异[ 15 ]。一项 2018 年在中国进行的三期临床试验表明,大约 40%的患者对利那洛肽治疗无反应,这可能是由于 IBS-C 的多因素病因[ 16 ]。迄今为止,IBS-C 的病因尚未完全阐明,以往的研究主要集中在与 IBS-C 密切相关肠道菌群的变化[ 17 ]。研究表明,肠道菌群不仅影响 IBS-C 的发生,还影响疾病治疗的疗效,包括结肠癌患者的化疗敏感性[ 18 ]、二甲双胍对糖尿病的影响[ 19 ]以及利福昔明治疗 IBS-D 的疗效[ 20 ]。通过动物实验,一项日本研究证实利那洛肽可以改善肾功能不全患者的肠道环境[ 21 ]。然而,利那洛肽是否能改善肠道菌群失调,以及肠道菌群是否与利那洛肽治疗 IBS-C 患者的症状缓解相关,仍有待确定。

Thus, the potential influence of the gut microbiota on the therapeutic effects of linaclotide has significant implications for IBS-C treatment. Through a multicenter clinical trial, this study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of linaclotide and discern the relationship between the relief provided by linaclotide treatment and alterations in the gut microbiota.

因此,肠道菌群对利那洛肽治疗效果的潜在影响对 IBS-C 治疗具有重要意义。本研究通过一项多中心临床试验,旨在评估利那洛肽的疗效与安全性,并阐明利那洛肽治疗提供的缓解效果与肠道菌群变化之间的关系。

Methods 方法

Subjects 受试者

This multicenter, pre-post clinical trial, which spanned a treatment period of six weeks, was conducted at six Chinese hospitals between January 2020 and June 2021 (Additional file 7: Table S1). The inclusion criteria for IBS-C patients were the following: ① age > 18 years, ② diagnosis of IBS-C (Rome IV diagnostic criteria), ③ Bristol type 1 or 2 > 25% [22], and ④ < 3 bowel movements per week. The exclusion criteria were as follows: ① pregnant or lactating women; ② patients with mental illness; ③ patients who consumed probiotics or antibiotics one month prior to the study; ④ patients who had undergone intestinal cleansing in the past two weeks; ⑤ patients allergic to the drugs used in the study; ⑥ patients with a history of digestive system tumors or gastrointestinal surgery, intestinal obstruction or gastrointestinal bleeding; and ⑦ patients with severe heart or lung diseases.

这项为期六周的、多中心的、前瞻性临床试验于 2020 年 1 月至 2021 年 6 月在中国六家医院进行(附加文件 7 : 表 S1)。IBS-C 患者的纳入标准如下:①年龄 > 18 岁,②符合 IBS-C 诊断标准(罗马 IV 诊断标准),③布里斯托类型 1 或 2 > 25% [ 22 ],④每周排便次数 < 3 次。排除标准如下:①孕妇或哺乳期妇女;②精神疾病患者;③研究前一个月内服用过益生菌或抗生素的患者;④过去两周内进行过肠道清洁的患者;⑤对研究中使用的药物过敏的患者;⑥有消化系统肿瘤或胃肠道手术、肠梗阻或胃肠道出血病史的患者;⑦患有严重心脏或肺部疾病的患者。

The exclusion criteria for the healthy volunteers were as follows: ① age < 18 years; ② use of antibiotics, probiotics, bowel cleansing products or proton-pump inhibitors within 1 month prior to the study; and ③ diagnosis of diseases such as IBS, inflammatory bowel disease, coeliac disease, or digestive system tumors or history of gastrointestinal surgery, intestinal obstruction or gastrointestinal bleeding, cardiac, renal or hepatic diseases, metabolic diseases, lactose intolerance, or active infection with pathogenic microorganisms.

健康志愿者的排除标准如下:①年龄<18 岁;②研究前 1 个月内使用抗生素、益生菌、肠道清洁产品或质子泵抑制剂;③患有 IBS、炎症性肠病、乳糜泻或消化系统肿瘤,或既往有胃肠道手术、肠梗阻或胃肠道出血病史,或患有心脏、肾脏或肝脏疾病、代谢性疾病、乳糖不耐受,或存在病原微生物的急性感染。

Treatment and follow-up 治疗和随访

All patients received the same dosage of linaclotide (290 μg orally once a day, half an hour before breakfast) for 6 weeks. The medication was supplied by AstraZeneca. All patients were followed up twice a week for 10 weeks post enrollment. The patients were not allowed to take any other constipation-related drugs, including probiotics and laxatives, during the treatment period. For patients with other diseases, treatment could be administered according to the established guidelines, with the requirement of keeping objective records.

所有患者均接受相同剂量的利那洛肽治疗(290 μg,每日早餐前半小时口服),持续 6 周。该药物由阿斯利康公司提供。所有患者在入组后均接受 10 周的每周两次随访。治疗期间,患者不得服用任何其他与便秘相关的药物,包括益生菌和泻药。对于患有其他疾病的患者,可根据既定指南进行治疗,并要求保持客观记录。

Collection of fecal samples

粪便样本收集

Fecal samples were collected before and after 6 weeks of linaclotide treatment. All samples were collected using a special stool collection tube in the hospital, and samples that did not come into any obvious contact with the external environment were collected with a stool shovel. Three stool samples (each consisting of at least 1 g) were collected from each patient, placed in a special refrigerator for specimen collection, stored at – 20 ℃, and rapidly transferred to − 80 ℃ by laboratory personnel within 4 h [23].

粪便样本在利那洛肽治疗 6 周前后进行收集。所有样本均使用医院特制的粪便收集管进行收集,未与外界环境发生明显接触的样本则使用粪便铲收集。每位患者收集三份粪便样本(每份至少 1 克),置于特制样本收集冰箱中,储存于–20℃,并由实验室人员在 4 小时内迅速转移至–80℃[ 23 ]。

Indicator collection 指标收集

The changes in abdominal pain (numeric rating scale (NRS), gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (GSRS), symptom severity score of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-SSS), and quality of life scale of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-QoLS)) were evaluated biweekly for 10 weeks, and the Bristol stool form scale (BSFS) and spontaneous bowel movements (SBMs) were assessed daily during treatment based on dietary conditions [24]. Drug-related side effects were also monitored. Fecal samples were collected before and 6 weeks after linaclotide administration. All these indicators were collected by trained personnel responsible for data collection at each center, and the organizing unit inspected and reassessed the data weekly. After treatment, the patients were categorized into relief and no relief groups. The patients in the relief group were further divided into responders and nonresponders based on the FDA response criteria [25].

腹部疼痛的变化(数字评分量表(NRS)、胃肠道症状评分量表(GSRS)、肠易激综合征症状严重程度评分(IBS-SSS)和肠易激综合征生活质量量表(IBS-QoLS))在 10 周内每两周评估一次,并在治疗期间根据饮食情况每日评估布里斯托大便形态量表(BSFS)和自发性排便(SBMs)[ 24 ]。同时监测药物相关副作用。粪便样本在给予利那洛肽前和 6 周后收集。所有这些指标均由各中心的负责数据收集的培训人员收集,组织单位每周检查并重新评估数据。治疗后,患者被分为缓解组和无缓解组。根据 FDA 反应标准[ 25 ],缓解组中的患者进一步分为应答者和非应答者。

The FDA response endpoint criteria for IBS-C were as follows: ① ≥ 30% reduction from baseline in the weekly mean of the daily scores for abdominal pain; ② ≥ 1 increase in the CSBM per week from baseline; and ③ improvement in abdominal pain and CSBM in the same week during at least 50% of the treatment period.

FDA 对 IBS-C 的响应终点标准如下:①腹痛每日评分的每周平均值较基线减少≥30%;②每周 CSBM 较基线增加≥1 次;③治疗期间至少 50%的周数腹痛和 CSBM 均有改善。

The relief criterion for IBS-C was the alleviation of abdominal pain or constipation during at least 50% of the treatment period.

IBS-C 的缓解标准是在治疗期间至少 50%的时间内缓解腹部疼痛或便秘。

16S rRNA sequencing 16S rRNA 测序

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, fluorescence quantification, MiSeq library construction and MiSeq sequencing were subsequently performed. PE reads obtained by MiSeq sequencing were first spliced according to overlap, and the sequence quality was then controlled and filtered. Operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering analysis and species taxonomy analysis were performed after sample segmentation. Multiple diversity indices could be analyzed based on the OTU clustering analysis results and the detected sequencing depth. Using taxonomic information, the community structure was statistically analyzed at each taxonomic level. Based on the abovementioned analysis, a series of in-depth statistical and visual analyses, including multivariate analysis and significance tests, were conducted to analyze the community composition and phylogenetic information of diverse species.

DNA 提取、PCR 扩增、荧光定量、MiSeq 文库构建和 MiSeq 测序随后进行。通过 MiSeq 测序获得的 PE 读段首先根据重叠进行拼接,然后进行序列质量控制和过滤。样本分割后进行操作分类单元(OTU)聚类分析和物种分类分析。基于 OTU 聚类分析结果和检测测序深度,可以分析多种多样性指数。利用分类信息,在各个分类水平上对群落结构进行统计分析。基于上述分析,进行一系列深入统计和可视化分析,包括多元分析和显著性检验,以分析不同物种的群落组成和系统发育信息。

Metabolomics testing 代谢组学检测

Appropriate amounts of pure standards of short-chain fatty acids, including acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, isobutyric acid, valeric acid, isovaleric acid and hexanoic acid, were used. Ten standard concentration gradients (0.02, 0.1, 0.5, 2, 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, and 500 μg/ml) were formulated with ether. An appropriate amount of sample was placed into a 2-ml centrifuge tube, and 50 μl of 15% phosphoric acid, 100 μl of 125 μg/ml internal standard (isohexic acid) solution, and 400 μl of ether were then added. After homogenization for 1 min, centrifugation was performed at 12,000 RPM at 4 ℃ for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected for testing. Appropriate chromatographic and mass spectrometry conditions were used. The precision, repeatability, and recovery were within a reasonable range.

使用了适量的短链脂肪酸纯标准品,包括乙酸、丙酸、丁酸、异丁酸、戊酸、异戊酸和己酸。使用乙醚配制了十个标准浓度梯度(0.02、0.1、0.5、2、10、25、50、100、250 和 500 μg/ml)。将适量的样品放入 2-ml 离心管中,然后加入 50 μl 15%磷酸、100 μl 125 μg/ml 内标(异己酸)溶液和 400 μl 乙醚。混合均匀 1 分钟后,在 4℃下以 12,000 RPM 离心 10 分钟,收集上清液进行检测。使用了适当的色谱和质谱条件。精密度、重复性和回收率均在合理范围内。

Statistical methods 统计方法

The appropriate statistical analysis for comparisons between groups was selected based on the data distribution and patient characteristics, and the analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 and IBM SPSS Statistics 26 software. The alpha diversity was determined by sampling-based OTU analysis, and the beta diversity was visualized and tested by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plots and analysis of similarities (ANOSIM). Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) was employed to analyze the differences in the bacterial community predominance between groups. Correlation analyses were performed using Spearman’s correlation. The data are presented as the means ± SDs, medians (P25-P75 values), medians (mix-max values), and n (%) values, and the significance was marked as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, and NS for no significance.

根据数据分布和患者特征选择了适当的统计分析方法,并使用 GraphPad Prism 8.0 和 IBM SPSS Statistics 26 软件进行数据分析。Alpha 多样性通过基于样本的 OTU 分析确定,Beta 多样性通过主坐标分析(PCoA)图和相似性分析(ANOSIM)进行可视化和检验。采用线性判别分析(LDA)分析组间细菌群落优势的差异。相关性分析采用 Spearman 相关性分析。数据以均值±标准差、中位数(P25-P75 值)、中位数(混合-最大值)和 n(%)表示,显著性标记如下:*p<0.05,**p<0.01,***p<0.001,****p<0.0001,无显著性用 NS 表示。

Results 结果

Patient demographics 患者人口统计学特征

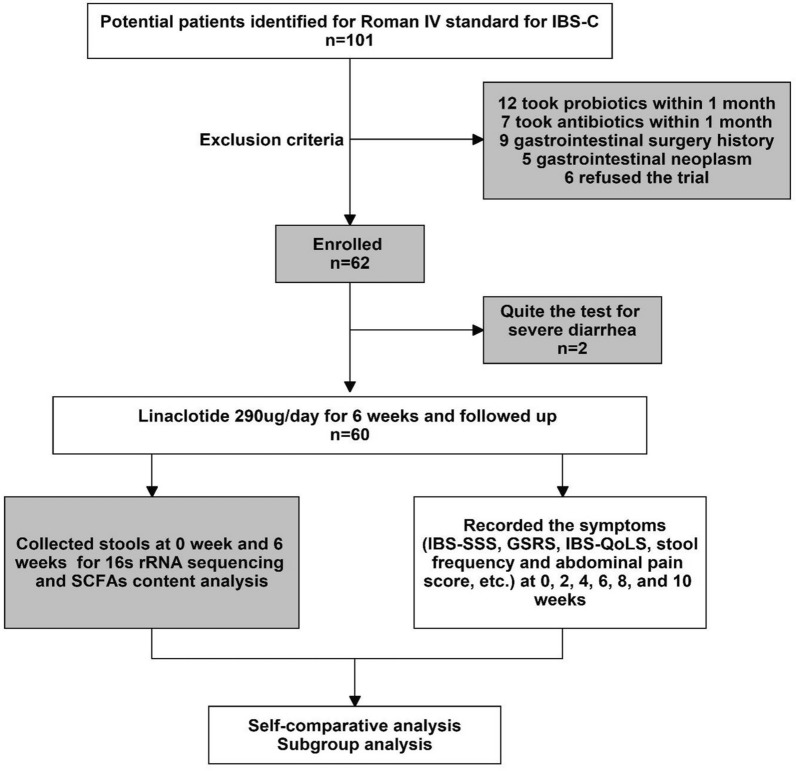

A total of sixty-two patients diagnosed with IBS-C were recruited for the study between January 2020 and June 2021. Two patients (3.2%) discontinued participation due to severe diarrhea (Fig. 1). Among the recruited IBS-C patients, 86.7% were female, and the average age, IBS-SSS score, and body mass index (BMI) of the patients were 45.2 ± 10.97 years, 225.17 ± 92.296, and 22.62 ± 2.76, respectively (Table 1). No significant differences in age, BMI, education, underlying diseases, or drug-related side effects were observed between the patients who experienced relief and those who did not (P > 0.05). Prior to linaclotide therapy, no significant differences in the IBS-SSS scores were found between the two groups (Table 1). Concurrently, a cohort of thirty healthy volunteers was enrolled, and no notable differences in baseline characteristics were observed between the group of volunteers and the IBS-C patient group (Additional file 8: Table S2). To mitigate the potential confounding effects of dietary factors on the gut microbiota, we assessed the nutrient intake of in IBS-C patients using a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [26], and no significant differences were found in the total calorie, protein, fat, fiber, or carbohydrate intake from baseline to week 10 (Additional file 9: Table S3).

研究于 2020 年 1 月至 2021 年 6 月期间招募了 62 名诊断为 IBS-C 的患者。其中两名患者(3.2%)因严重腹泻而退出研究(图 1 )。在招募的 IBS-C 患者中,86.7%为女性,患者的平均年龄、IBS-SSS 评分和体重指数(BMI)分别为 45.2 ± 10.97 岁、225.17 ± 92.296 和 22.62 ± 2.76(表 1 )。在缓解组和未缓解组之间,年龄、BMI、教育程度、基础疾病或药物相关副作用无显著差异(P > 0.05)。在利那洛肽治疗之前,两组的 IBS-SSS 评分无显著差异(表 1 )。同时,还招募了 30 名健康志愿者,志愿者组与 IBS-C 患者组在基线特征方面无显著差异(附加文件 8 :表 S2)。 为减轻饮食因素对肠道菌群可能产生的混杂效应,我们使用食物频率问卷(FFQ)[ 26 ]评估了 IBS-C 患者的营养摄入情况,从基线到第 10 周,总热量、蛋白质、脂肪、纤维或碳水化合物摄入量均未发现显著差异(附加文件 9 :表 S3)。

Fig. 1. 图 1。

Clinical trial flow chart

临床试验流程图

Table 1. 表 1。

The demographics of patients

患者的基线资料

| Total (N = 60) 总计(N=60) | Non-relief (n = 9) 未缓解(n=9) | Relief (n = 51) 缓解(n=51) | P value P 值 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n,%) 性别(n,%) | Female 女性 | 52 (86.7) | 9 (100) | 43 (84.31) | 0.024 |

| Male 男性 | 8 (13.3) | 0 (0) | 8 (15.69) | ||

| Age 年龄 | Median (P25-P75) 中位数(P25-P75) | 47 (36.5 – 51.75) 47 (36.5–51.75) | 40 (33 – 50.5) 40 (33–50.5) | 47 (38 – 53) 47 (38–53) | 0.722 |

| Mean ± SD 均值±标准差 | 45.2 ± 10.97 | 42.89 ± 10.96 | 45.61 ± 11.16 | ||

| BMI | Median (P25-P75) 中位数(P25-P75) | 22.48 (21.26 – 23.99) 22.48 (21.26–23.99) | 21.78 (18.598 – 23.05) 21.78 (18.598–23.05) | 22.58 (21.34 – 24.28) 22.58 (21.34–24.28) | 0.100 |

| Mean ± SD 均值±标准差 | 22.62 ± 2.76 | 20.94 ± 3.3 | 22.92 ± 2.75 | ||

| Education 教育 | Primary 主要 | 6 (10) | 0 (0) | 6 (11.76) | 0.495 |

| Medium 中等 | 32 (53.3) | 7 (77.78) | 25 (49.02) | ||

| Higher 较高 | 22 (36.7) | 2 (22.22) | 20 (39.22) | ||

| IBS-SSS | Median (P25-P75) 中位数(P25-P75) | 225 (156.25 – 275) 225 (156.25–275) | 225 (162.5 – 342.5) 225 (162.5–342.5) | 225 (125 – 275) 225 (125–275) | 0.445 |

| (Baseline) (基线) | Mean ± SD 均值±标准差 | 225.17 ± 92.296 225.17±92.296 | 245.56 ± 86.05 | 221.57 ± 86.89 | |

| Basic disease * 基本疾病 | No 否 | 56 (93.3) | 9 (100) | 47 (92.16) | 0.347 |

| Yes 是 | 4 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (7.84) | ||

|

Drug-related 药物相关 side effects # 副作用 # |

No 不 | 44 (73.3) | 8 (88.89) | 36 (70.59) | 0.360 |

| Yes 是 | 16 (26.7) | 1 (11.11) | 15 (29.41) |

BMI body mass index, IBS-SSS irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity scale

BMI 体重指数,IBS-SSS 肠易激综合征症状严重程度量表

*4 reported hypertension; # 16 reported diarrhea

* 4 人报告高血压;16 人报告腹泻

Clinical efficacy of linaclotide

利那洛肽的临床疗效

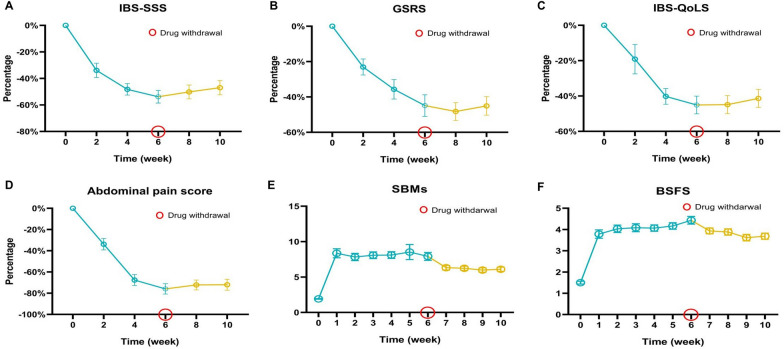

To evaluate the impact of linaclotide, we collected relevant clinical data (see the supplementary data and patient information table for detailed information). The IBS-SSS, GSRS, IBS-QoLS, and abdominal pain scores gradually decreased over six weeks compared with the baseline scores (Fig. 2A-D). The BSFS scores and number of SBMs progressively increased during the six weeks of treatment (Fig. 2E, F. After the six-week medication period, we conducted a four-week follow-up. During this period, the IBS-SSS, GSRS, IBS-QoLS, abdominal pain, BSFS, and SBM scores of the patients remained stable. By applying the FDA response endpoint criteria, we determined that 43.3% (26/60) of patients achieved the FDA response endpoint. Eighty-five percent (51/60) of the patients reported some relief. Among the patients who did not meet the FDA response criteria, 73.5% (25/34) reported at least some alleviation of abdominal pain and constipation with clinical relief, whereas 26.5% (9/34) reported no relief over six-week treatment course. These findings highlight the interindividual variation in the therapeutic efficacy of linaclotide.

为评估利那洛肽的影响,我们收集了相关的临床数据(详见补充数据和患者信息表以获取详细信息)。与基线评分相比,IBS-SSS、GSRS、IBS-QoLS 和腹痛评分在六周内逐渐下降(图 2 A-D)。BSFS 评分和 SBM 数量在六周的治疗期间逐渐增加(图 2 E, F)。在六周的用药期结束后,我们进行了四周的随访。在此期间,患者的 IBS-SSS、GSRS、IBS-QoLS、腹痛、BSFS 和 SBM 评分保持稳定。通过应用 FDA 响应终点标准,我们确定 43.3%(26/60)的患者达到了 FDA 响应终点。85%(51/60)的患者报告了某种程度的缓解。在未达到 FDA 响应标准的患者中,73.5%(25/34)报告了腹痛和便秘至少有所减轻,并出现临床缓解,而 26.5%(9/34)报告在六周的治疗过程中未得到缓解。这些发现突出了利那洛肽治疗效力的个体差异。

Fig. 2. 图 2。

Changes in symptom scores during 6 weeks of treatment and 4 weeks of withdrawal. The irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity scale (IBS-SSS) (A), gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (GSRS) (B), irritable bowel syndrome quality of life questionnaire (IBS-QoLS) (C), and abdominal pain score (D) significantly decreased during 6 weeks of treatment, and these scores remained stable for four weeks after withdrawal. The Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) (E) and spontaneous bowel movements (SBMs) (F) improved during the treatment and drug withdrawal periods

治疗 6 周和停药 4 周期间症状评分的变化。肠易激综合征症状严重程度量表(IBS-SSS)(A)、胃肠道症状评分量表(GSRS)(B)、肠易激综合征生活质量问卷(IBS-QoLS)(C)和腹痛评分(D)在治疗 6 周期间显著下降,这些评分在停药后四周内保持稳定。布里斯托大便量表(BSFS)(E)和自发性排便(SBMs)(F)在治疗和停药期间得到改善

Linaclotide altered the intestinal flora of IBS-C patients

利那洛肽改变了 IBS-C 患者的肠道菌群

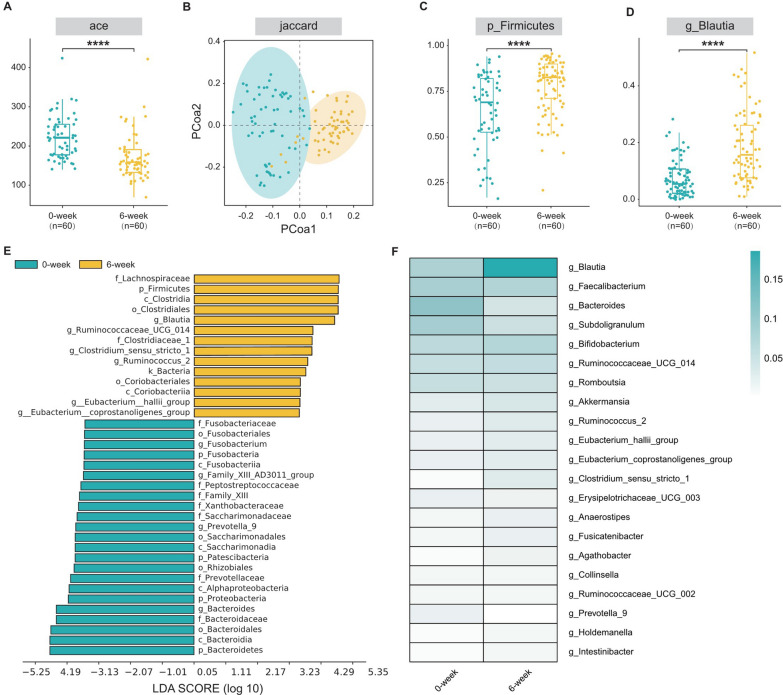

To investigate whether the effect of linaclotide treatment was associated with changes in the gut microbiota, we collected initial (0-week) and final (6-week) fecal samples from 60 patients and performed high-throughput gene sequencing analysis of 16S rRNA to analyze the gut microbial composition. We assessed the alpha diversity of the gut microbiota using various methodologies through a generalized linear model, and consistent results across different indices (ACE and Chao1) revealed that the 6-week group exhibited significantly higher alpha diversity than the 0-week group (p < 0.0001; Fig. 3A, Additional file 10: Table S4). To further elucidate the differences in the gut microbial composition, we evaluated the beta diversity through principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) using the Jaccard distance algorithm. Clear clustering separation of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) indicated distinct community structures between the 0-week and 6-week groups, indicating significant differences in the structures (Fig. 3B).

为探究利那洛肽治疗的效果是否与肠道菌群的变化相关,我们从 60 名患者中收集了初始(0 周)和最终(6 周)的粪便样本,并进行了 16S rRNA 高通量基因测序分析,以分析肠道微生物组成。我们通过广义线性模型,采用多种方法评估了肠道菌群的α多样性,不同指数(ACE 和 Chao1)的一致结果表明,6 周组的α多样性显著高于 0 周组(p < 0.0001;图 3 A,附加文件 10 :表 S4)。为进一步阐明肠道微生物组成的差异,我们使用 Jaccard 距离算法进行主坐标分析(PCoA)评估了β多样性。操作分类单元(OTU)的清晰聚类分离表明 0 周组和 6 周组之间存在不同的群落结构,表明结构存在显著差异(图 3 B)。

Fig. 3. 图. 3.

The efficacy of linaclotide in the treatment of IBS-C was related to its ability to modulate the gut microbiota. A Changes in alpha diversity indices. B Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the gut microbiota. C, D The abundance of Firmicutes at the phylum level and that of Blautia at the genus level were greater after 6 weeks of treatment than at 0 weeks. E Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) was used to estimate the impact of the abundance of each component (genus) on the effects. F Community heatmap generated using color gradients to represent the size of the data in a two-dimensional matrix or table and to present community species composition information. ACE, Jaccard, and the abundances of Firmicutes and Blautia were adjusted for the IBS-SSS baseline score, sex, age, BMI, education, basic disease status, and nutrient status by repeated-measures ANOVA

利那洛肽在治疗 IBS-C 中的疗效与其调节肠道菌群的能力相关。A 肠道菌群α多样性指数的变化。B 肠道菌群的主坐标分析(PCoA)。C、D 在治疗 6 周后,厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)在门水平上的丰度以及布劳蒂亚菌属(Blautia)在属水平上的丰度均高于 0 周。E 采用线性判别分析(LDA)来估计每个组分(属)丰度对疗效的影响。F 使用颜色渐变表示二维矩阵或表格中数据的规模,并呈现群落物种组成信息的群落热图。通过重复测量 ANOVA 对 ACE、Jaccard、厚壁菌门和布劳蒂亚菌属的丰度进行校正,校正因素包括 IBS-SSS 基线评分、性别、年龄、BMI、教育程度、基础疾病状态和营养状态。

Subsequently, we conducted a comprehensive examination of the gut microbiota landscape in all available samples to further explore the potential composition differences between the 0-week and 6-week groups. At the phylum level, Firmicutes constituted the most abundant phylum, accounting for 63.81% and 77.93% of the gut microbial community in the 0-week and 6-week groups, respectively (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3C, Additional file 11: Table S5). Notably, at the genus level, distinct differences in the biological composition were observed between the two groups. We analyzed bacterial genera with a relative abundance exceeding 1%. Among them, the genera Blautia (18.57% vs. 7.77%, respectively; p < 0.001) (Fig. 3D, Additional file 12: Table S6) and Fusicatenibacter (1.23% vs. 1.69%, respectively; p < 0.001) (Additional file 12: Table S6) exhibited relatively higher abundances in the 6-week group. We also compared the taxonomic compositions at the class/order/family level between the two groups (Additional file 1: Figure S1B-D, Additional file 13: Table S7, Additional file 14: Table S8, Additional file 15: Table S9) and detected significant differences in the abundances of Lachnospiraceae, Clostridiales and Clostridia, to which Blautia belong, between before and after treatment.

随后,我们对所有可用样本的肠道菌群景观进行了全面分析,以进一步探索 0 周组和 6 周组之间潜在的组成差异。在门水平上,厚壁菌门是含量最丰富的门,分别占 0 周组和 6 周组肠道微生物群落的 63.81%和 77.93%(p < 0.0001)(图 3 C,附加文件 11 :表 S5)。值得注意的是,在属水平上,两组在生物学组成上存在明显差异。我们分析了相对丰度超过 1%的细菌属。其中,布劳蒂亚属(18.57% vs. 7.77%,分别;p < 0.001)(图 3 D,附加文件 12 :表 S6)和纤维弧菌属(1.23% vs. 1.69%,分别;p < 0.001)(附加文件 12 :表 S6)在 6 周组中相对丰度较高。 我们还比较了两组在科/目/科水平上的分类组成(附加文件 1 :图 S1B-D,附加文件 1 3 :表 S7,附加文件 1 4 :表 S8,附加文件 1 5 :表 S9),并检测到在治疗后,与普拉梭菌属(Blautia)所属的毛螺菌科、梭菌目和梭菌纲的丰度存在显著差异。

To confirm the specific bacterial taxa affected by linaclotide treatment, linear discriminant analysis of effect size (LEfSe) was used for high-dimensional class comparisons, revealing significant differences in the predominance of the bacterial communities between the two groups (Fig. 3E, Additional file 2: Figure S2A). According to the results, the genus Blautia (from the phylum Firmicutes and the family Lachnospiraceae) emerged as a key bacterial type contributing to gut microbiota dysbiosis in the 6-week group. Additionally, a heatmap comparing the gut microbiota between the two groups based on the OTU abundance was generated at the genus level, further demonstrating the relatively higher abundance of the genus Blautia in the 6-week group, which aligned with the findings from the LEfSe analysis (Fig. 3F).

为确认利那洛肽治疗影响的具体细菌类群,采用高维分类比较的线性判别分析效应大小(LEfSe)方法,揭示了两组间细菌群落组成存在显著差异(图 3 E,附加文件 2 :图 S2A)。根据结果,厚壁菌门毛螺菌科中的属 Blautia 成为导致 6 周组肠道菌群失调的关键细菌类型。此外,基于 OTU 丰度在属水平上比较两组肠道菌群的差异热图显示,6 周组中 Blautia 属的相对丰度较高,这与 LEfSe 分析结果一致(图 3 F)。

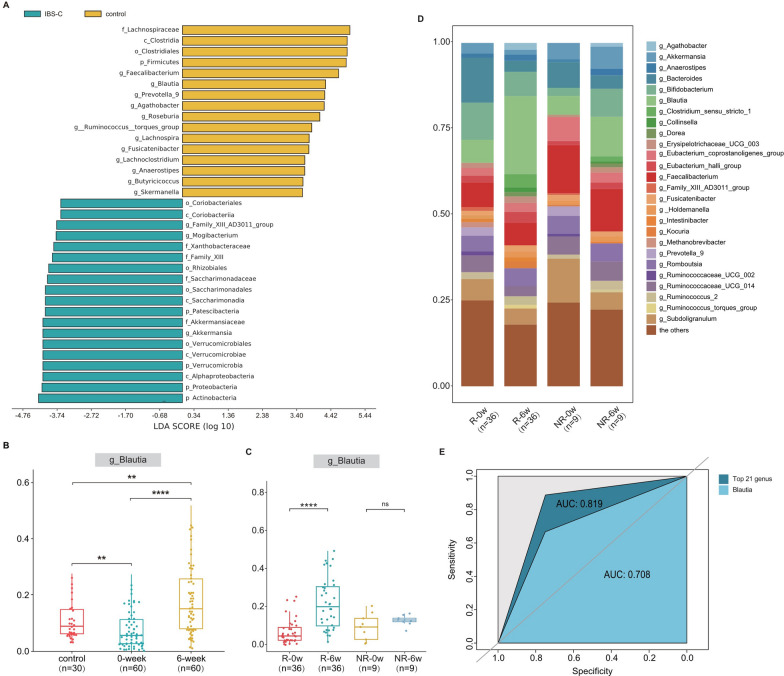

Moreover, we analyzed the differences in the gut microflora between healthy volunteers and IBS-C patients. The LEfSe results indicated that Firmicutes at the phylum level and Blautia at the genus level were predominant in the healthy volunteers (Fig. 4A). In contrast, IBS-C patients exhibited a lower abundance of Blautia than did healthy volunteers, whereas the abundance of Blautia after linaclotide treatment was higher than that of the healthy volunteers (Fig. 4B). In addition, in the continuous observation (4 weeks after linaclotide withdrawal), we also found that Blautia remained higher than pretherapy, but lower than the period of treatment (Additional file 3: Figure S3). These findings further support the notion that linaclotide may exert its effects by modulating the intestinal flora.

此外,我们分析了健康志愿者和 IBS-C 患者肠道菌群的差异。LEfSe 结果指出,在门水平上厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)和在属水平上布劳蒂亚菌属(Blautia)在健康志愿者中占主导地位(图 4 A)。相比之下,IBS-C 患者的布劳蒂亚菌属丰度低于健康志愿者,而接受利那洛肽治疗后,布劳蒂亚菌属的丰度高于健康志愿者(图 4 B)。此外,在持续观察(利那洛肽停药后 4 周)期间,我们发现布劳蒂亚菌属的丰度仍高于治疗前水平,但低于治疗期间(附加文件 3 :图 S3)。这些发现进一步支持利那洛肽可能通过调节肠道菌群发挥其作用的观点。

Fig. 4. 图 4.

Linaclotide mitigated IBS-C in individual patients to different extents, and the detected increase in the abundance of Blautia was effective at alleviating the symptoms of IBS-C caused by linaclotide. A Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) of effect size (LEfSe) was used to estimate the impact of the abundance of each component on the different effects between IBS-C patients and control individuals (healthy volunteers). B The abundance of Blautia at the genus level was highest in the 6-week group, followed by the control group (healthy volunteers), and the 0-week group had the lowest abundance. C, D Abundance of Blautia in the relief and no-relief patients before and after treatment. E Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the top twenty-one bacteria at the genus level and Blautia for separate prediction; the area under the curve (AUC) is shown

利那洛肽对不同患者的 IBS-C 症状缓解程度有所不同,检测到的 Blautia 丰度增加对缓解利那洛肽引起的 IBS-C 症状有效。采用效应大小线性判别分析(LEfSe)来估计各组分丰度对 IBS-C 患者与对照组(健康志愿者)之间不同效应的影响。B Blautia 属水平丰度在 6 周组最高,其次是对照组(健康志愿者),0 周组丰度最低。C、D 治疗前后缓解组和非缓解组 Blautia 丰度。E 顶层二十一种属水平细菌和 Blautia 的单独预测受试者工作特征(ROC)曲线;显示曲线下面积(AUC)。

The abundance of Blautia was related to the efficacy of linaclotide

布劳蒂亚的丰度与利那洛肽的疗效相关

A relationship between the abundance of Blautia and the effectiveness of linaclotide treatment was observed in this study. To control for confounding factors such as sex, age, and BMI, a ratio of 1:4 was used to match 9 patients who did not experience relief (NR) and 36 out of 51 patients who reported relief [27]. Stool specimens collected at 0 and 6 weeks were also analyzed (Additional file 4: Figure S4A-E), which demonstrated that the overall structure and alpha diversity of the gut microbiota did not differ between the relief and no relief patients (Additional file 5: Figure S5A, B). Interestingly, more pronounced symptom relief was observed if the Blautia abundance after treatment was markedly higher than that before treatment (Fig. 4C, D. We also investigated the predictive ability of the intestinal flora by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and found that the baseline abundance at the genus level could be used to predict the efficacy of the IBS-C treatment with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.819, and Blautia (AUC of 0.708) was among the top 21 genera (Fig. 4E). These findings suggested that some specific gut microbes, such as Blautia, exhibited a significant (p < 0.01) difference in their impact on the effect of linaclotide between patients who experienced relief and those who did not.

本研究观察到普拉梭菌丰度与利那洛肽治疗效果之间存在关联。为控制性别、年龄和 BMI 等混杂因素,采用 1:4 的比例匹配了 9 例未缓解(NR)患者和 51 例中报告缓解的 36 例患者[ 27 ]。同时分析了 0 周和 6 周收集的粪便标本(附加文件 4 :图 S4A-E),结果显示缓解组和非缓解组的肠道菌群整体结构和α多样性无差异(附加文件 5 :图 S5A, B)。有趣的是,若治疗后普拉梭菌丰度显著高于治疗前,则症状缓解更为明显(图 4 C, D)。我们还通过受试者工作特征(ROC)分析研究了肠道菌群预测能力,发现属水平上的基线丰度可用于预测 IBS-C 治疗效果,曲线下面积(AUC)为 0.819,其中普拉梭菌(AUC 为 0.708)位列前 21 个属之中(图 4 E)。 这些发现表明,某些特定的肠道微生物,如布劳蒂亚,在缓解症状的患者和未缓解症状的患者之间,对利那洛肽疗效的影响存在显著差异(p < 0.01)。

The Blautia and SCFA levels were positively correlated with the alleviation of clinical symptoms

布劳蒂亚和短链脂肪酸水平与临床症状的缓解呈正相关

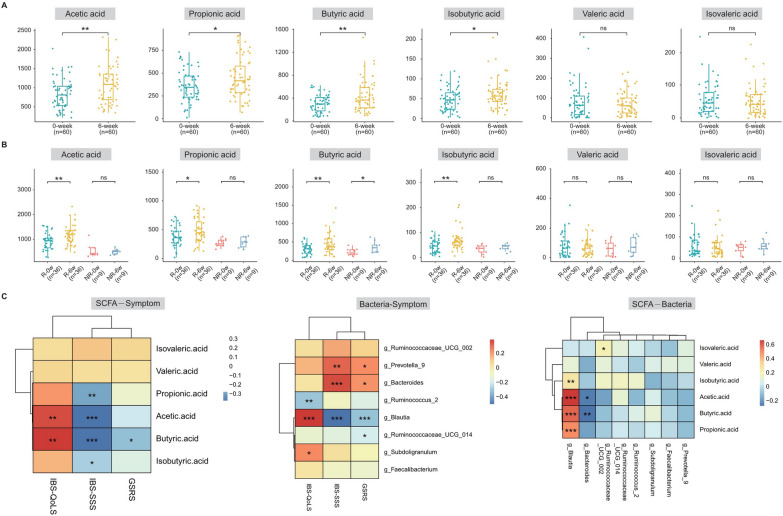

According to relevant studies, Blautia species are SCFA-producing bacteria. A metabolomic analysis of fecal samples revealed that the concentrations of acetic acid (p < 0.01), propionic acid (p < 0.05), butyric acid (p < 0.01) and isobutyric acid (p < 0.05) were significantly increased in the feces of IBS-C patients treated with linaclotide for 6 weeks (Fig. 5A). A comparison between the relief and no relief groups demonstrated significantly higher levels of acetic acid (p < 0.0001), propionic acid (p < 0.0001), and isobutyric acid (p < 0.001) in the relief group after the treatment (Fig. 5B). We then performed a correlation analysis to investigate the relationships among the abundance of Blautia, the content of SCFAs, and clinical symptoms. Interestingly, we found a positive relationship between the abundance of Blautia and the contents of acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid. Increased IBS-QoLS and decreased IBS-SSS and GSRS scores were positively correlated with the Blautia abundance. Additionally, increased IBS-QoLS and decreased IBS-SSS scores were positively correlated with the contents of acetic acid and butyric acid (Fig. 5C). These findings suggest that Blautia may play a crucial role in the efficacy of linaclotide treatment.

根据相关研究,布劳蒂亚属是产生短链脂肪酸的细菌。对粪便样本进行的代谢组学分析显示,接受利那洛肽治疗 6 周的 IBS-C 患者粪便中乙酸(p < 0.01)、丙酸(p < 0.05)、丁酸(p < 0.01)和异丁酸(p < 0.05)的浓度显著升高(图 5 A)。缓解组与未缓解组的比较显示,治疗后缓解组的乙酸(p < 0.0001)、丙酸(p < 0.0001)和异丁酸(p < 0.001)水平显著更高(图 5 B)。我们随后进行了相关性分析,以研究布劳蒂亚丰度、短链脂肪酸含量与临床症状之间的关系。有趣的是,我们发现布劳蒂亚丰度与乙酸、丙酸和丁酸含量之间存在正相关关系。IBS-QoLS 评分升高和 IBS-SSS、GSRS 评分降低与布劳蒂亚丰度呈正相关。此外,IBS-QoLS 评分升高和 IBS-SSS 评分降低与乙酸和丁酸含量呈正相关(图 5 C)。 这些发现表明,布劳蒂亚可能在利那洛肽治疗的疗效中发挥关键作用。

Fig. 5. 图 5。

The levels of bacteria and their metabolites were positively correlated with clinical symptoms. A Concentrations of acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, isobutyric acid, isovalerate acid, and valerate acid in the feces of IBS-C patients before and after linaclotide treatment. B Concentrations of acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, isobutyric acid, isovalerate acid, and valerate acid in the feces of relief and no-relief IBS-C patients after treatment. C Correlations among the Blautia abundance, differential short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) content and clinical symptoms

细菌及其代谢物的水平与临床症状呈正相关。

A 治疗前和治疗后 IBS-C 患者粪便中乙酸、丙酸、丁酸、异丁酸、异戊酸和戊酸浓度。

B 治疗后缓解组和非缓解组 IBS-C 患者粪便中乙酸、丙酸、丁酸、异丁酸、异戊酸和戊酸浓度。

C Blautia 丰度、差异短链脂肪酸(SCFA)含量与临床症状的相关性

Discussion 讨论

In this study, we demonstrated that linaclotide can improve defecation, relieve abdominal symptoms, and modify bowel evacuation habits in most IBS-C patients, and diarrhea is a common side effect. These results align with previous phase III clinical findings in China [16]. However, the results revealed individual differences in treatment effectiveness, which can potentially be attributed to the multifactorial nature of the pathophysiology. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota has been identified as an important pathogenic factor in IBS-C patients [28]. Moreover, accumulating evidence has indicated that patients with IBS-C have intestinal microecological imbalances [29]. For example, IBS-C patients exhibit a higher gut microbial diversity and have a higher relative abundance of stool methanogens, predominantly Methanobrevibacter [17]. Although the mechanism through which intestinal microecological imbalance leads to IBS-C has not been fully elucidated, this imbalance possibly involves an excessively long retention time of feces in the intestinal tract, which changes the quantity and balance of intestinal microbes and the metabolites of the flora (SCFAs), the cellular components of the bacteria (lipopolysaccharides), or the interactions between the bacteria and the host immune system, all of which affect a variety of intestinal functions [30, 31].

在本研究中,我们证明了利那洛肽可以改善排便、缓解腹部症状,并改变大多数 IBS-C 患者的肠道排空习惯,腹泻是常见的副作用。这些结果与中国先前进行的 III 期临床研究结果一致[ 16 ]。然而,研究结果揭示了治疗效果的个体差异,这可能与病理生理的多因素性质有关。肠道菌群失调已被确定是 IBS-C 患者的重要致病因素[ 28 ]。此外,越来越多的证据表明,IBS-C 患者存在肠道微生态失衡[ 29 ]。例如,IBS-C 患者表现出更高的肠道微生物多样性,并且粪便甲烷菌的相对丰度更高,主要是布劳氏甲烷菌[ 17 ]。 尽管肠道微生态失衡导致 IBS-C 的机制尚未完全阐明,但这种失衡可能涉及粪便在肠道内停留时间过长,从而改变肠道微生物的数量和平衡,以及菌群代谢产物(短链脂肪酸)、细菌的细胞成分(脂多糖)或细菌与宿主免疫系统的相互作用,所有这些都影响多种肠道功能[ 30 , 31 ]。

Hence, we performed 16S sequencing on the stool of IBS-C patients collected before and after treatment for 6 weeks. The results showed that linaclotide could affect the intestinal flora, and our study also showed an increased abundance of Blautia and Fusicatenibacter in IBS-C patients after linaclotide treatment, even after adjusting for age, diet, and other factors. Recently, Tomita et al. reported “a significant reduction in the abundance of Fusicatenibacter in CD patients with IBS-D-like symptoms [32].” However, because the abundance of Fusicatenibacter was low and no significant enrichment of bacteria after linaclotide treatment was observed via LEfSe analysis, we mainly analyzed Blautia. A phase II clinical study recently found that MRx1234, which contains a strain of Blautia hydrogenotrophica, could improve the abdominal pain score and significantly improve the bowel habit rate of IBS-C patients [33]. In particular, we discovered that IBS-C patients exhibited a lower abundance of Blautia than healthy volunteers did, which illustrated that Blautia has the potential to become a novel, safe treatment option. As a member of the Firmicutes phylum, Blautia has shown promise in alleviating inflammatory and metabolic diseases because it has antibacterial activity against specific microorganisms [34, 35]. The composition and abundance of Blautia in the intestine are influenced by various factors, including diet, age, health, disease state, genotype, geography, and physiological conditions [36–38]. These findings align with the experimental results obtained in this study.

因此,我们对接受治疗 6 周的 IBS-C 患者治疗前后粪便样本进行了 16S 测序。结果表明利那洛肽可以影响肠道菌群,我们的研究也显示利那洛肽治疗后 IBS-C 患者中布劳蒂亚和纤维弧菌的丰度增加,即使在调整年龄、饮食等因素后也是如此。最近,Tomita 等人报道“患有 IBS-D 样症状的克罗恩病患者中纤维弧菌的丰度显著降低[ 32 ]。”然而,由于纤维弧菌的丰度较低,且通过 LEfSe 分析未观察到利那洛肽治疗后细菌显著富集,因此我们主要分析了布劳蒂亚。最近的一项 II 期临床研究发现,含有布劳蒂亚氢化酶菌菌株的 MRx1234 可以改善腹痛评分,并显著改善 IBS-C 患者的肠道习惯率[ 33 ]。特别是我们发现 IBS-C 患者的布劳蒂亚丰度低于健康志愿者,这表明布劳蒂亚有可能成为一种新型、安全的治疗选择。 作为厚壁菌门的一个成员,布劳蒂亚因对特定微生物具有抗菌活性,在缓解炎症和代谢性疾病方面显示出潜力[ 34 , 35 ]。肠道中布劳蒂亚的组成和丰度受多种因素影响,包括饮食、年龄、健康状况、疾病状态、基因型、地理环境和生理条件[ 36 – 38 ]。这些发现与本研究获得的实验结果一致。

Moreover, the influence of the intestinal flora on dozens of clinical drugs has been revealed. A previous study highlighted the complex bidirectional interactions between the gut microbiota and various clinical drugs. The gut microbiome can be influenced by drugs, and vice versa, the gut microbiome can influence the treatment efficacy of drugs by impacting the drug structure and altering its bioavailability, biological activity or toxicity (pharmaceutical microbiology) [39]. In our study, we also found a significant increase in the Blautia abundance in the relief group but not in the no-relief group, indicating that linaclotide may modulate the Blautia abundance as part of its mechanism of action.

此外,肠道菌群对数十种临床药物的影响已被揭示。一项先前的研究强调了肠道菌群与各种临床药物之间的复杂双向相互作用。药物可以影响肠道菌群,反之,肠道菌群可以通过影响药物结构并改变其生物利用度、生物活性或毒性(药物微生物学)[ 39 ]。在我们的研究中,我们也发现缓解组的 Blautia 显著增加,而非缓解组没有增加,这表明利那洛肽可能通过调节 Blautia 丰度来发挥其作用机制的一部分。

Previous studies have elucidated the role of Blautia as a commensal anaerobic bacterium that helps maintain the intestinal environmental balance, prevents inflammation, increases intestinal regulatory T cells, and produces SCFAs [40–42]. The total SCFA concentration in IBS-C patients was lower than that in healthy individuals, mainly due to reduced acetic acid and propionic acid levels [43]. In addition, the level of SCFAs is related to the viscosity of the stool of IBS patients [44]. If the stool texture of IBS-C patients (whose main clinical manifestation is constipation) is dry, the corresponding SCFA content also decreases. In our study, positive correlations were found among symptom improvement, the Blautia abundance, and the SCFA concentration, indicating that the therapeutic effect of linaclotide may involve increasing the SCFA concentrations through modulation of the intestinal flora, particularly by increasing the Blautia abundance. These results suggest that the gut microbiota and its metabolites may contribute to linaclotide treatment and its therapeutic effects (Additional file 6: Figure S6).

既往研究已阐明布劳蒂亚作为一种共生厌氧菌,在维持肠道环境平衡、预防炎症、增加肠道调节性 T 细胞及产生短链脂肪酸(SCFAs)方面发挥作用[ 40 – 42 ]。IBS-C 患者的总 SCFA 浓度低于健康个体,主要由于乙酸和丙酸水平降低[ 43 ]。此外,SCFAs 水平与 IBS 患者粪便粘度相关[ 44 ]。若 IBS-C 患者(其主要临床表现为便秘)的粪便质地干燥,相应的 SCFA 含量也会降低。本研究发现症状改善、布劳蒂亚丰度和 SCFA 浓度之间存在正相关,表明利那洛肽的治疗效果可能通过调节肠道菌群,特别是增加布劳蒂亚丰度,从而提高 SCFA 浓度。这些结果表明肠道菌群及其代谢物可能参与利那洛肽治疗及其治疗效果(附加文件 6 :图 S6)。

This study has several limitations. First, this study was not a randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical study, and the sample size was not sufficiently large. Second, gender based differences on IBS were clearly reported, and most IBS-C patients were female [45, 46]. Although the gender distribution of our patients showed the phenomenon above and we conduct a self-controlled pre-post study to exclude gender interference factor, we could not get valid results on gender differences in linaclotide treatment. Third, the effect of linaclotide on the intestinal flora has been reported only in China and has not been investigated in other regions. However, additional studies are needed to confirm this phenomenon.

这项研究存在一些局限性。首先,本研究并非随机、对照、双盲的临床试验,样本量也不够大。其次,关于性别对 IBS 的影响已有明确报道,大多数 IBS-C 患者为女性[ 45 , 46 ]。尽管我们患者的性别分布显示出上述现象,并且我们进行了自我对照的前后研究以排除性别干扰因素,但我们未能获得关于利那洛肽治疗中性别差异的有效结果。第三,利那洛肽对肠道菌群的影响仅在 中国 有报道,尚未在其他地区进行调查。然而,需要进一步的研究来证实这一现象。

Conclusions 结论

In summary, our study demonstrated that the gut microbiota may be not only necessary but also sufficient to mediate the effect of linaclotide in clinical settings. The efficacy of linaclotide is associated with modulation of the Blautia abundance and SCFA concentration. The abundance of Blautia after treatment could be used to predict the efficacy of linaclotide. Treatment with linaclotide supplemented with Blautia may be a potential method for improving the overall efficacy of clinical treatment for IBS-C.

总之,我们的研究表明,肠道菌群不仅可能是,而且足够介导利那洛肽在临床环境中的效果。利那洛肽的有效性与布劳蒂亚的丰度和短链脂肪酸浓度的调节有关。治疗后布劳蒂亚的丰度可用于预测利那洛肽的有效性。补充布劳蒂亚的利那洛肽治疗可能是提高 IBS-C 临床治疗效果的潜在方法。

Supplementary Information

补充信息

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Stacked bar chart. The taxonomic compositions of the 0-week and 6-week groups were compared at the phylum (A), class (B), order (C), family (D) and genus (E) levels.

附加文件 1:图 S1。堆叠条形图。比较了 0 周组和 6 周组的门(A)、纲(B)、目(C)、科(D)和属(E)水平的分类组成。

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Clade evolution map of the 0-week and 6-week groups.

附加文件 2:图 S2. 0 周组和 6 周组的类群进化图

Additional file 3: Figure S3. Abundance of Blautia at each time point.

附加文件 3:图 S3. 每个时间点的 Blautia 含量。

Additional file 4: Figure S4. Stacked bar chart. The taxonomic compositions of the relief and no relief groups were compared at the phylum (A), class (B), order (C), family (D), and genus (E) levels.

附加文件 4:图 S4. 堆叠条形图。比较了缓解组和未缓解组的门(A)、纲(B)、目(C)、科(D)和属(E)水平的分类组成。

Additional file 5: Figure S5. Changes in alpha diversity indices (A) and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the gut microbiota (B) of patients in the relief and no relief groups.

附加文件 5:图 S5. 缓解组和未缓解组患者的肠道菌群 alpha 多样性指数(A)和主坐标分析(PCoA)(B)的变化。

Additional file 6: Figure S6. Schematic illustration of the study.

附加文件 6:图 S6. 研究示意图。

Additional file 7: Table S1. Source of the patients.

附加文件 7:表 S1. 患者来源。

Additional file 8: Table S2. Demographics of the normal population and IBS-C patients.

附加文件 8:表 S2. 正常人群和 IBS-C 患者的基线资料。

Additional file 9: Table S3. Nutrient intake in patients with different prognoses.

附加文件 9:表 S3. 不同预后患者的营养摄入。

Additional file 10: Table S4. Comparison of the α diversity between before and after treatment.

附加文件 10:表 S4. 治疗前后 α 多样性的比较。

Additional file 11: Table S5. Comparison of gut microbes at the phylum level between before and after treatment.

附加文件 11:表 S5. 治疗前后门水平肠道微生物的比较。

Additional file 12: Table S6. Comparison of gut microbes at the genus level between before and after treatment.

附加文件 12:表 S6. 治疗前后肠道菌属水平比较。

Additional file 13: Table S7. Comparison of gut microbes at the class level between before and after treatment.

附加文件 13:表 S7. 治疗前后肠道菌科水平比较。

Additional file 14: Table S8. Comparison of gut microbes at the order level between before and after treatment.

附加文件 14:表 S8. 治疗前后肠道菌目水平比较。

Additional file 15: Table S9. Comparison of gut microbes at the family level between before and after treatment.

附加文件 15:表 S9. 治疗前后肠道菌群的科水平比较。

Acknowledgements 致谢

We would like to additionally thank Xin Xiong and Jinneng Wang for helping with the sample collection and Yuanyuan Lei and Dianji Tu for their expertise and help with the 16S sequencing experiments. We are also grateful for all the patients who participated in the study. None of the patients received any compensation.

我们还要特别感谢熊欣和王锦程在样本收集方面的帮助,以及雷媛媛和涂典基在 16S 测序实验方面的专业指导和帮助。我们同样感谢所有参与研究的患者。所有患者均未获得任何报酬。

Abbreviations 缩写

- ANOSIM

Analysis of similarities 相似性分析

- AUC

Area under the curve 曲线下面积

- BMI

Body mass index 身体质量指数

- BSFS

Bristol Stool Function Scale

布里斯托大便功能量表- CIC

Chronic idiopathic constipation

慢性特发性便秘- FDA

Food and drug administration

食品药品监督管理局- FFQ

Food frequency questionnaire

食物频率问卷- GSRS

Gastrointestinal symptom rating scale

胃肠道症状评分量表- IBS

Irritable bowel syndrome 肠易激综合征

- IBS-C

Irritable bowel syndrome with constipation

肠易激综合征伴便秘- IBS-D

Irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea

腹泻型肠易激综合征- IBS-QoLS

Quality of life scale of irritable bowel syndrome

肠易激综合征生活质量量表- IBS-SSS

Symptom severity score of irritable bowel syndrome

肠易激综合征症状严重程度评分- LDA

Linear discriminant analysis

线性判别分析- LEfSe

LDA of effect size 效应量 LDA

- NRS

Numeric Rating Scales 数字评分量表

- OTU

Operational taxonomic unit

操作分类单元- PCoA

Principal coordinate analysis

主成分分析- SBMs

Spontaneous bowel movements

自发性排便- SCFA 短链脂肪酸

Short-chain fatty acid 短链脂肪酸

Author contributions 作者贡献

JZ, SH, SG, XY, JZ, CH, HW and RM performed the patient recruitment and data collection; BT and XX performed the data processing and monitoring; XX, LT, AZ and HL analyzed the data; JZ, HW, AZ, BH, XL and TZ performed the animal experiments; JY and HW wrote versions of the manuscript; and SH, SG, and SY conceived the study, interpreted the results and supervised the research.

JZ、SH、SG、XY、JZ、CH、HW 和 RM 负责患者招募和数据收集;BT 和 XX 负责数据处理和监控;XX、LT、AZ 和 HL 分析数据;JZ、HW、AZ、BH、XL 和 TZ 进行动物实验;JY 和 HW 撰写稿件;SH、SG 和 SY 构思研究、解释结果并监督研究。

Funding 资助

This work was supported by the Chongqing Science and Technology Commission (cstc2020jscx-msxmX0129) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81874196).

这项工作得到了重庆市科学技术委员会(cstc2020jscx-msxmX0129)和中国国家自然科学基金(81874196)的支持。

Availability of data and materials

数据和材料的可用性

All the data generated or analyzed in the current study are included in this published article (and Additional files). Prof. Shiming Yang and Dr. Jianyun Zhou had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

本研究产生或分析的所有数据均包含在本已发表的论文中(以及附加文件)。杨世明教授和周建云博士可以完全访问研究中的所有数据,并对数据的完整性和数据分析的准确性负责。

Declarations 声明

Ethics approval and consent to participate

伦理批准和参与同意

The trial adhered to ethical guidelines and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Xinqiao Hospital, Third Military Medical University (Ethical Review No. 2019-125-01).

该试验遵循伦理指南,并获得了第三军医大学新桥医院伦理委员会的批准(伦理审查编号 2019-125-01)。

Consent for publication 发表同意

Not applicable. 不适用。

Competing interests 竞争利益

All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

所有作者声明他们没有利益冲突。

Footnotes 脚注

Publisher's Note 出版商须知

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Springer Nature 对已发表的地图中的领土主张和机构隶属关系保持中立。

Jianyun Zhou, Haoqi Wei, An Zhou and Xu Xiao have contributed equally to this study.

Jianyun Zhou、Haoqi Wei、An Zhou 和 Xu Xiao 对这项研究贡献相同。

Contributor Information 作者信息

Suyu He, Email: hesuyu2009@163.com.

Suyu He,邮箱:hesuyu2009@163.com。

Sai Gu, Email: 1601792466@qq.com.

Sai Gu,邮箱:1601792466@qq.com。

Shiming Yang, Email: 13228686589@163.com.

杨世明,邮箱:13228686589@163.com。

References 参考文献

-

1.Lacy BE, Chey WD, Lembo AJ. New and emerging treatment options for irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2015;11:1–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1.Lacy BE, Chey WD, Lembo AJ. 新型和新兴的肠易激综合征治疗选择. 纽约胃肠病学与肝病杂志 2015;11:1–19. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

2.Endo Y, Shoji T, Fukudo S. Epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28:158–159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2.Endo Y, Shoji T, Fukudo S. 肠易激综合征的流行病学. 消化内科杂志 2015;28:158–159. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

3.Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, et al. American college of gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(Suppl 1):S2–26. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3.Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, 等. 美国胃肠病学学会关于肠易激综合征和慢性特发性便秘管理的论著. 美国胃肠病学杂志. 2014;109(Suppl 1):S2–26. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.187. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

4.Liu JJ, Brenner DM. Review article: current and future treatment approaches for IBS with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54(Suppl 1):S53–S62. doi: 10.1111/apt.16607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4.Liu JJ, Brenner DM. 综述文章: 肠易激综合征合并便秘的当前和未来治疗方法. 药物与营养治疗. 2021;54(Suppl 1):S53–S62. doi: 10.1111/apt.16607. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] - 5.Camilleri M. American college of gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16(5):629–632. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.1002770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukudo S, Kaneko H, Akiho H, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(1):11–30. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-1017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Chey WD, et al. American college of gastroenterology monograph on management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(Suppl 2):1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busby RW, Bryant AP, Bartolini WP, et al. Linaclotide, through activation of guanylate cyclase C, acts locally in the gastrointestinal tract to elicit enhanced intestinal secretion and transit. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;649:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryant AP, Busby RW, Bartolini WP, et al. Linaclotide is a potent and selective guanylate cyclase C agonist that elicits pharmacological effects locally in the gastrointestinal tract. Life Sci. 2010;86:760–765. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farmer AD, Ruffle JK, Hobson AR. Linaclotide increases cecal pH, accelerates colonic transit, and increases colonic motility in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Neurogastroent Motil. 2018;31(2):e13492. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao SSC, Xiang X, Yan Y, et al. Randomised clinical trial: linaclotide vs placebo-a study of bi-directional gut and brain axis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51(12):1332–1341. doi: 10.1111/apt.15772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao SSC, Quigley EMM, Shiff SJ, et al. Effect of Linaclotide on severe abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:616–623. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chey WD, Sayuk GS, Bartolini W, et al. Randomized trial of 2 delayed-release formulations of linaclotide in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(2):354–361. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sayuk GS. Linaclotide: promising IBS-C efficacy in an era of provisional study endpoints. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(11):1726–1729. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang L, Lacy BE, Moshiree B, et al. Efficacy of linaclotide in reducing abdominal symptoms of bloating, discomfort, and pain: a phase 3B trial using a novel abdominal scoring system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(9):1929–1937. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Fang J, Guo X, et al. Linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: a phase 3 randomized trial in China and other regions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33(5):980–989. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villanueva-Millan MJ, Leite G, Wang J, et al. Methanogens and hydrogen sulfide producing bacteria guide distinct gut microbe profiles and irritable bowel syndrome subtypes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(12):2055–2066. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu T, Guo F, Yu Y, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes chemoresistance to colorectal cancer by modulating autophagy. Cell. 2017;170(3):548–563.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin N-R, Lee J-C, Lee H-Y, et al. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice. Gut. 2014;63(5):727–735. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Hong G, Yang M, et al. Fecal bacteria can predict the efficacy of rifaximin in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Pharmacol Res. 2020;159:104936. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanto-Hara F, Kanemitsu Y, Fukuda S, et al. The guanylate cyclase C agonist Linaclotide ameliorates the gut–cardio–renal axis in an adenine-induced mouse model of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2020;35:250–264. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfz126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aziz I, Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, et al. An approach to the diagnosis and management of Rome IV functional disorders of chronic constipation. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;14(1):39–46. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2020.1708718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McIntosh K, Reed DE, Schneider T, et al. FODMAPs alter symptoms and the metabolome of patients with IBS: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2017;66(7):1241–1251. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Q, Liang S, Jia H, et al. Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Nat Commun. 2015;11(6):6528. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Macdougall JE, et al. Responders vs clinical response: a critical analysis of data from linaclotide phase 3 clinical trials in IBS-C. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26(3):326–333. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips CM, Shivappa N, Hébert JR, et al. Dietary inflammatory index and biomarkers of lipoprotein metabolism, inflammation and glucose homeostasis in adults. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):1033. doi: 10.3390/nu10081033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herman J, Pokkunuri V, Braham L, et al. Gender distribution in irritable bowel syndrome is proportional to the severity of constipation relative to diarrhea. Gend Med. 2010;7:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pittayanon R, Lau JT, Yuan Y, et al. Gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(1):97–108. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenner DM, Harris LA, Chang CH, et al. Real-world treatment strategies to improve outcomes in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(4S):S21–S26. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimidi E, Christodoulides S, et al. Mechanisms of action of probiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota on gut motility and constipation. Adv Nutr. 2017;8(3):484–494. doi: 10.3945/an.116.014407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015;313(9):949–958. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomita T, Fukui H, Morishita D, et al. Diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome-like symptoms in patients with quiescent crohn's disease: comprehensive analysis of clinical features and intestinal environment including the gut microbiome, organic acids, and intestinal permeability. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;29(1):102–112. doi: 10.5056/jnm22027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quigley EMM, Markinson L, Stevenson A, et al. Randomised clinical trial: efficacy and safety of the live biotherapeutic product MRx1234 in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023;57(1):81–93. doi: 10.1111/apt.17310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chakravarthy SK, Jayasudha R, Prashanthi GS, et al. Dysbiosis in the gut bacterial microbiome of patients with uveitis, an inflammatory disease of the eye. Indian J Microbiol. 2018;58(4):457–469. doi: 10.1007/s12088-018-0746-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khattab MSA, Abd El Tawab AM, Fouad MT. Isolation and characterization of anaerobic bacteria from frozen rumen liquid and its potential characterizations. Int J Dairy Sci. 2017;12(1):47–51. doi: 10.3923/ijds.2017.47.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Odamaki T, Kato K, Sugahara H, et al. Age-related changes in gut microbiota composition from newborn to centenarian: a cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0708-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakayama J, Watanabe K, Jiang J, et al. Diversity in gut bacterial community of school-age children in Asia. Sci Rep-Uk. 2015;5(1):8397. doi: 10.1038/srep08397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mao B, Gu J, Li D, et al. Effects of different doses of fructooligosaccharides (fos) on the composition of mice fecal microbiota, especially the Bifidobacterium composition. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):1105. doi: 10.3390/nu10081105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maier L, Typas A. Systematically investigating the impact of medication on the gut microbiome. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2017;39:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim CH, Park J, Kim M, et al. Gut Microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids, t cells, and inflammation. Immune Netw. 2014;14(6):277–288. doi: 10.4110/in.2014.14.6.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang C, He X, Sheng Y, et al. Allicin-induced host-gut microbe interactions improve energy homeostasis. FASEB J. 2020;34(8):10682–10698. doi: 10.1096/fj.202001007R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu X, Mao B, Gu J, Chen W, et al. Blautia-a new functional genus with potential probiotic properties? Gut Microbes. 2021;13(1):1–21. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1875796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gargari G, Taverniti V, Gardana C, et al. Fecal clostridiales distribution and short-chain fatty acids reflect bowel habits in irritable bowel syndrome. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20(9):3201–3213. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ringel-Kulka T, Choi CH, Temas D, et al. Altered colonic bacterial fermentation as a potential pathophysiological factor in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(9):1339–1346. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palsson OS, Whitehead W, Törnblom H, et al. Prevalence of Rome IV functional bowel disorders among adults in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1262–1273.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pecyna P, Gabryel M, Mankowska-Wierzbicka D, et al. Gender influences gut microbiota among patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:10424. doi: 10.3390/ijms241310424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Stacked bar chart. The taxonomic compositions of the 0-week and 6-week groups were compared at the phylum (A), class (B), order (C), family (D) and genus (E) levels.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Clade evolution map of the 0-week and 6-week groups.

Additional file 3: Figure S3. Abundance of Blautia at each time point.

Additional file 4: Figure S4. Stacked bar chart. The taxonomic compositions of the relief and no relief groups were compared at the phylum (A), class (B), order (C), family (D), and genus (E) levels.

Additional file 5: Figure S5. Changes in alpha diversity indices (A) and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the gut microbiota (B) of patients in the relief and no relief groups.

Additional file 6: Figure S6. Schematic illustration of the study.

Additional file 7: Table S1. Source of the patients.

Additional file 8: Table S2. Demographics of the normal population and IBS-C patients.

Additional file 9: Table S3. Nutrient intake in patients with different prognoses.

Additional file 10: Table S4. Comparison of the α diversity between before and after treatment.

Additional file 11: Table S5. Comparison of gut microbes at the phylum level between before and after treatment.

Additional file 12: Table S6. Comparison of gut microbes at the genus level between before and after treatment.

Additional file 13: Table S7. Comparison of gut microbes at the class level between before and after treatment.

Additional file 14: Table S8. Comparison of gut microbes at the order level between before and after treatment.

Additional file 15: Table S9. Comparison of gut microbes at the family level between before and after treatment.

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated or analyzed in the current study are included in this published article (and Additional files). Prof. Shiming Yang and Dr. Jianyun Zhou had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.