The anti-immigration backlash comes to Japan

反移民浪潮襲捲日本

It was always bound to happen.

這是必然會發生的事。

照片由 Mottinn 透過維基共享資源提供

We often talk about ways in which Japan is ahead of other developed nations; in the old days, people said this about technology, while more recently it’s usually about social trends like sexless youth. But when I lived there, I often noted ways in which Japan was behind the U.S. Trends in fashion, music, and culture seemed to get popular in Japan about five to ten years after their heyday in America.1

我們經常討論日本在哪些方面領先其他發達國家;過去人們談論技術,而最近通常是關於性冷淡青年等社會趨勢。但當我居住在那裡時,我常常注意到日本落後於美國的方面。在時尚、音樂和文化趨勢上,通常在美國達到顛峰後 5 至 10 年才在日本流行。1

For a long time, mainstream Japanese politics was essentially devoid of the type of xenophobic, conspiratorial, nativist populism that has defined the MAGA movement in America and parties like AfD in Europe. The late Abe Shinzo, Japan’s prime minister from 2012 to 2020, had the reputation of being a rightist. But in fact, he governed as much more of a Reaganite conservative, or sometimes even a liberal; he opened the country to immigration and supported women in the workplace. When an anti-Korean hate group arose in the early 2010s, Abe passed Japan’s first law against hate speech and put the hate group on a watch list, ultimately demolishing it as a political force.

長期以來,日本主流政治基本上缺乏在美國 MAGA 運動和歐洲如德國另類選擇黨(AfD)中定義的仇外、陰謀論、本土民粹主義。2012 年至 2020 年間擔任日本首相的安倍晉三被認為是右派。但事實上,他的執政更像是雷根式保守派,有時甚至是自由派;他對移民持開放態度,並支持職場女性。在 2010 年初出現反韓仇恨團體時,安倍通過了日本第一部反仇恨言論法,並將該團體列入觀察名單,最終摧毀了其作為政治力量的基礎。

But like raves and backwards baseball caps, Trumpian politics has finally made it to Japan’s shores. A new political party called Sanseito2 has won a surprising number of seats in Japan’s recent Upper House election, running on a platform that mostly looks like it was copied directly from MAGA:

但就像聚會和反戴帽子一樣,川普式政治終於登陸日本。一個名為「三成黨 2」的新政黨在日本最近的參議院選舉中贏得了令人驚訝的席次,其政見基本上看起來直接抄襲自 MAGA:

Its leader is a former supermarket manager who…campaigned on the Trumpian message “Japanese First.”…Now Japan’s burgeoning right-wing populist party Sanseito has…bagged 14 seats [out of 248] in Japan’s upper house…

其領導人是一位前超市經理,曾……以特朗普式的「日本優先」訊息競選……現在,日本新興的右翼民粹主義政黨三聲黨已……在日本上議院贏得 14 個席次【總共 248 個席次中】……Party leader Sohei Kamiya founded the group in 2020 by “gathering people on the Internet,” then gradually began winning seats in local assemblies…It gained traction during the Covid pandemic, during which it spread conspiracy theories about vaccinations and a cabal of global elites…[I]n the run-up to the upper house elections, it became better known for its “Japanese First” campaign – which focused on complaints of overtourism and the influx of foreign residents…Sanseito tapped into these frustrations on its “Japanese First” platform, along with other complaints about stagnant wages, high inflation and costs of living…

黨魁神谷誠平於 2020 年透過「在網路上召集人群」成立了這個政黨,然後逐漸開始贏得地方議會席次……該黨在新冠疫情期間引起關注,期間散佈疫苗陰謀論和全球精英陰謀……[在]上議院選舉前,該黨以「日本優先」競選活動而更為人知——聚焦於過度旅遊和外籍居民湧入的抱怨……三聲黨藉由「日本優先」平台觸及這些不滿情緒,同時也包括對停滯工資、高通膨和生活成本的其他抱怨……The party supports caps on the number of foreign residents in each town or city, more restrictions on immigration and benefits available to foreigners, and making it harder to naturalize as citizens…Sanseito is also pushing for stronger security measures and anti-espionage laws, greater tax cuts, renewable energy, and a health system that leans away from vaccines.

該黨支持限制每個城鎮或城市的外國居民人數,對移民和外國人可獲得的福利設置更多限制,並使歸化入籍更加困難……三成黨還推動更嚴格的安全措施和反間諜法律,提供更大的減稅力度、可再生能源,以及一個不太依賴疫苗的醫療系統。

Some of this — for example, the antivax stuff and the ranting about globalist elites — is clearly just the spread of memes from the U.S. and Europe to Japan. Kamiya Sohei, the party’s leader, even said some stuff about “Jewish capital” in a speech; Japan’s banks have essentially zero Jews in them, so you know this is just something he read on the internet.

部分內容——例如反疫苗言論和抨擊全球主義精英——明顯是美國和歐洲的意識形態在日本的傳播。該黨領袖神谷壯平甚至在演講中談到了"猶太資本";日本的銀行基本上沒有猶太人,所以你知道這只是他在網路上讀到的東西。

But the party’s main issue — restrictions on immigration and tourism — isn’t just mimicry of Trump or AfD. Instead, it’s a response to a real and important trend that has affected the entire world, and happened to hit Japan a little later than other countries.

但該黨的主要議題——限制移民和旅遊——並非純粹模仿特朗普或德國另類選擇黨。相反,這是對一個影響全球的真實且重要趨勢的回應,只是在日本的出現比其他國家晚了一些。

There are three main reasons for the global migration boom. The first is the internet; as people in the developing world get more information about how to move to rich countries, and learn what life in rich countries is like, a lot more of them get the idea to move. The second reason is global development; as each country first starts to escape poverty, its people get enough money to move out.3

全球移民潮有三個主要原因。第一是網際網路;當發展中國家的人們獲得更多關於如何遷移到富裕國家的資訊,並了解富裕國家的生活,越來越多人開始考慮移民。第二個原因是全球發展;當一個國家剛開始擺脫貧困時,人們就有足夠的錢進行遷移。

The third reason is low fertility rates. All rich countries now have fertility rates that will cause them to dwindle and shrink in the long term. This causes labor shortages in many industries. Rather than accept large-scale economic and social disruption from labor shortages, essentially every rich country eventually chooses to turn to immigration to plug those gaps. Japan took a little longer to reach this decision, but ultimately it ended up doing much the same thing everyone else did:

第三個原因是低生育率。所有富裕國家現在的生育率都會導致長期人口縮減。這造成許多產業的勞動力短缺。與其接受勞動力短缺帶來的大規模經濟和社會破壞,幾乎每個富裕國家最終都選擇通過移民來填補這些空缺。日本花了比較長的時間做出這個決定,但最終還是採取了與其他國家類似的做法。

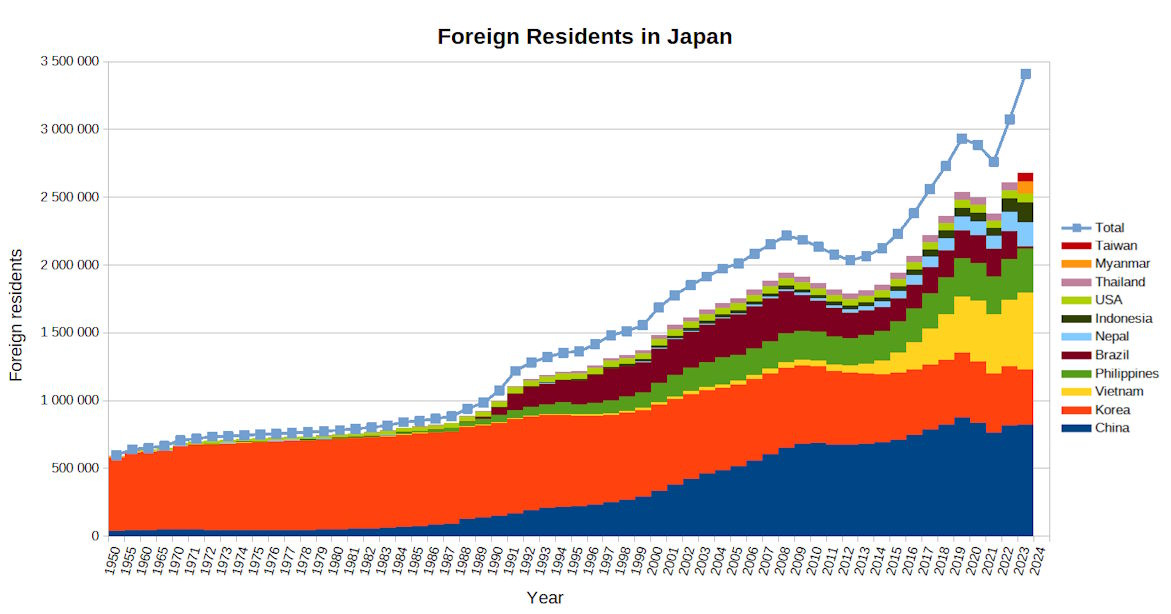

If you want the detailed story of how and why Japan opened itself up to immigration, read that post. But the basic story is that Japan has, in fact, opened itself up to immigration:

如果您想了解日本開放移民的詳細過程和原因,請閱讀那篇文章。但基本的故事是,日本確實已經開放了移民:

來源:MrThe1And0nly via Wikimedia Commons

The “Korean” people on this chart are almost all “zainichi” people, whose ancestors immigrated from Korea and who have South or North Korean passports and citizenship (Japan does not have birthright citizenship), but who are functionally Japanese. The real influx of foreigners only started in the 1990s, and it was only around 2013 that true permanent mass immigration began. That immigration is mostly from Vietnam, the Philippines, and Nepal, though some other Southeast Asian countries, as well as the U.S. and Taiwan, are starting to figure into the mix as well.

圖表上的「韓國」人幾乎都是「在日」人,他們的祖先從韓國移民,持有南韓或北韓護照和公民身份(日本並沒有出生公民權),但實際上是日本社會的一員。外國人的真正流入是在 1990 年代開始,直到 2013 年前後才真正開始大規模的永久移民。這些移民主要來自越南、菲律賓和尼泊爾,不過一些其他東南亞國家,以及美國和台灣也開始逐漸加入這個移民組合。

I travel to Japan quite frequently, and this immigration is very noticeable. Plenty of convenience stores have Nepalese and Chinese clerks; plenty of restaurants have Vietnamese cooks. Also keep in mind that the numbers above count only the foreign-born, not the children of the foreign-born; Japan’s youth are diversifying more rapidly than the population as a whole.

我經常到日本旅行,移民現象非常明顯。許多便利商店都有尼泊爾人和中國人擔任店員;很多餐廳都有越南廚師。還要注意,上述數字僅統計外籍出生者,不包括外籍移民的子女;日本的年輕族群正比整體人口更快速地走向多元化。

In fact, it’s an open question whether this immigration will degrade some of the special characteristics that make Japan such a great place to live in the first place. Japan is not the U.S. — it’s not a nation of immigrants, and it has traditionally defined its national identity in terms of a unique culture that newcomers don’t share.

事實上,這種移民是否會降低使日本成為宜居之地的特殊特徵,這仍是一個開放性的問題。日本不是美國——它不是一個移民國家,而且傳統上一直以獨特的文化定義其民族認同,而新來者並不共享這種文化。

Could immigration change Japan for the worse?

移民真的會讓日本變得更糟嗎?

Other than making it slightly harder to talk to convenience store clerks, mass immigration hasn’t yet really changed the face of Tokyo, Osaka, or other big Japanese cities. But in specific areas, immigration is forcing big local changes to Japan’s way of life. There are now over 200,000 Muslims in Japan; mosques, Muslim schools, and Muslim graveyards4 have radically reshaped some neighborhoods.

除了讓便利商店員工略微難以溝通之外,大規模移民尚未真正改變東京、大阪或其他大型日本城市的面貌。但在特定地區,移民正迫使日本生活方式發生巨大的變化。目前日本已有超過 20 萬名穆斯林;清真寺、穆斯林學校和穆斯林墓地已徹底改變了一些社區。

Then there’s the possibility of crime. Unlike the United States, Japan’s society functions on the assumption of almost zero violent crime. Its famously safe streets give women and children the freedom to walk around at night alone without worrying — a freedom that’s totally alien to Americans, and a constant source of wonder for people who visit Japan. The assumption of total public safety also allows cities to be built with a level of walkability and density that the crime-ridden U.S. shies away from.

還有犯罪的可能性。與美國不同,日本社會基於幾乎零暴力犯罪的假設。其著名的安全街道讓婦女和兒童可以放心地獨自在夜晚行走——這種自由對美國人來說完全陌生,也是造訪日本的人們不斷驚嘆的源頭。公共安全的絕對假設還允許城市以一種罪案叢生的美國不敢嘗試的步行性和密度建設城市。

Immigrants in Japan are generally surprisingly well-behaved. Unlike in the U.S., the average immigrant in Japan is going to tend to be a little more rowdy and unruly than the locals, just because Japan is one of the most peaceful countries on Earth to behin with. But acculturation is real and powerful; people tend to follow the social norms of the people around them, so when you drop a random American or Australian in the middle of urban Japan, even if he was a gangster back home, he’ll probably follow the rules like everyone else does. (In fact, I knew two such former gangsters in Osaka.)

在日本的移民通常出奇地守規矩。不同於美國,在日本的平均移民可能比當地人更吵鬧和難以管理,因為日本本來就是地球上最和平的國家之一。但文化融合是真實且強大的;人們往往會遵循周圍人的社會規範,所以當你把一個隨機的美國人或澳洲人丟進日本城市的中心,即使他在家鄉曾是個惡棍,他可能也會像其他人一樣遵守規則。(事實上,我在大阪認識兩個這樣的前惡棍。)

On average, it looks like foreigners get arrested at a bit less than twice the rate of native-born Japanese people. Given the very low baseline, this isn’t a very significant amount of crime. Japan has a murder rate of about 0.23; even doubling that would still leave them safer than Korea or China, so increasing it by a far smaller percent via immigration isn’t going to change the nation’s fundamental character. Immigrant crime isn’t a big deal in Japan…yet.

平均來說,外國人的犯罪率似乎比本地出生的日本人略高一倍。考慮到非常低的基準線,這並不是一個非常顯著的犯罪數量。日本的謀殺率約為 0.23;即使翻倍也仍然比韓國或中國安全,所以通過移民增加的比例遠小,不會改變國家的根本特性。目前,移民犯罪在日本還不是大問題。

But if the foreign-born population of Japan keeps growing, will this still hold true? If Japan’s population goes from 3% foreign born to 16% — the level of the UK — there will be large enclaves where foreigners and their descendants live out their lives mostly surrounded by each other instead of by Japanese people.

但是,如果日本的外籍人口持續增長,情況還會是這樣嗎?如果日本的外籍人口從 3%增長到 16%——與英國相同的水平——屆時將會出現大片聚居區,外國人及其後代主要生活在彼此周圍,而不是與日本人接觸。

At that point, will acculturation to low crime rates break down? That’s probably what happened in France, where “banlieue” immigrant neighborhoods are high in crime and have seen frequent rioting, despite the overall peacefulness of the country. It would be a shame to see Japan forced to become like France, with guards armed with machine guns standing on street corners. The loss of the ability of women and children to walk safely alone at night in urban areas would be a tragedy. The scary thing here is that we don’t really know if this will happen, or how much immigration it would take to bring it about…and we won’t ever know, unless and until we wake up and find that it’s already too late.

屆時,低犯罪率的文化同化會否瓦解?這可能是法國發生的情況,那裡的移民社區(「banlieue」)犯罪率高,且常有暴動,儘管整體國家仍相當和平。如果日本被迫變得像法國一樣,讓持機關槍的警衛站在街頭,那將是令人遺憾的。女性和兒童無法在城市夜晚安全獨自行走,將是一場悲劇。可怕的是,我們實際上並不知道這種情況是否會發生,或需要多少移民才會導致這種結果……除非我們醒悟過來,發現一切已經太遲了。

So it’s reasonable for Japanese people to be uneasy about the possibility of continued mass immigration. In fact, although I’m personally an advocate of continued large-scale immigration in America, I’m pretty apprehensive about the prospect when it comes to Japan. And I can understand why some Japanese people are apprehensive as well.

因此,日本人對持續大規模移民的可能性感到不安是合理的。事實上,儘管我個人支持美國持續的大規模移民,但在談到日本時,我也頗為擔心。我可以理解為什麼一些日本人會感到不安。

The overtourism problem 過度旅遊問題

In fact, I think there’s another reason for the rise of nativist politics in Japan: the overtourism problem.

事實上,我認為日本本土政治興起還有另一個原因:過度旅遊問題。

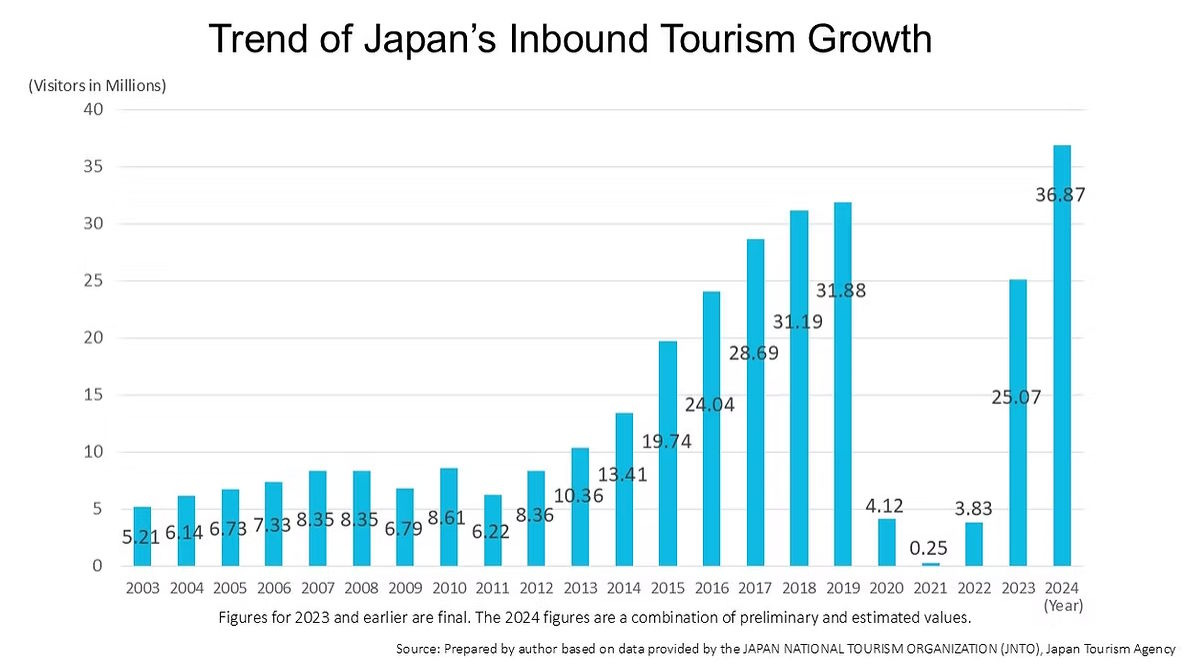

In recent years, thanks in part to a concerted decades-long campaign by the national government, the entire world has learned that Japan is an easy place to visit and get around in. Translation apps, Google Maps, cheap international roaming, and Apple Pay have made it even easier. Japan is an incredibly unique, pleasant, and fun place, and it’s also now a cheap place for foreigners, thanks to the recent weakening of the yen. Everyone who recommends travel destinations says the same thing: Go to Japan.

近年來,部分歸功於國家政府長期的協調努力,全世界已經了解日本是一個容易訪問和四處走動的地方。翻譯應用程式、Google 地圖、便宜的國際漫遊和 Apple Pay 使這一切變得更加容易。日本是一個極其獨特、令人愉悅且有趣的地方,現在由於日元的近期貶值,對外國人來說也是一個便宜的目的地。所有推薦旅遊目的地的人都說同一件事:去日本。

As a result, Japan has become absolutely flooded with tourists. In 2024 the country probably received about 37 million travelers:

因此,日本完全被遊客淹沒。2024 年,該國可能接待了約 3,700 萬名旅客:

If this boom were dispersed evenly throughout time and space, it wouldn’t be very onerous. If every tourist came for only one week, and they were spread out evenly throughout the year, 37 million annual visitors would represent only 0.6% of the Japanese population. That’s tiny.

The problem is that the tourists are not spread out evenly through time and space. They crowd into a few places — the west side of Tokyo, the older neighborhoods of Kyoto — at a few times during the year. During the cherry blossom season in late March and early April, west Tokyo feels as international as NYC. The coffee shops and restaurants and parks are crammed with foreigners, few of whom can speak Japanese. Train stations are jammed up with tourists fumbling with their payment cards at the ticket gate. It’s almost impossible to get a dinner reservation.

In some neighborhoods, the crush goes away during off-season, but some of Japan’s most beautiful and vibrant spots have been hollowed out into tourist traps. Golden Gai, a small drinking district which houses some of Tokyo’s coolest little bars, is now almost entirely tourists. Shibuya, once the beating heart of Japan’s youth culture, is now a museum of itself. Akihabara is no longer the haunt of anime nerds and social outcasts, but a place where tourists go to shop at a shrinking number of increasingly generic stores.

Nowhere has it worse than Kyoto. Reeves Wiedeman had a great travel report in the Intelligencer the other day, illustrating how everything that made Kyoto interesting and distinctive has been either chased away by a constant choking throng of tourists, or crassly commercialized to sell to foreigners.

京都的情況最為嚴重。Reeves Wiedeman 最近在 Intelligencer 上發表了一篇精彩的旅遊報告,闡述了絡繹不絕的遊客如何驅趕或粗暴地將京都原本獨特有趣的一切商業化,賣給外國人。

This is what economists call a “congestion externality”. If only one tourist goes to Shibuya, she can get lost in a neon wonderland; if a million tourists go to Shibuya, the neon wonderland gets replaced by something empty and tawdry, and no one gets to enjoy it.

這就是經濟學家所說的「擁擠外部性」。如果只有一個遊客來到澀谷,她可以迷失在霓虹燈的奇幻世界;但如果有一百萬遊客來到澀谷,那麼這個霓虹奇幻世界將被取代為空洞且庸俗的景象,結果是沒人能享受到。

Congestion externalities also strain the efficient public transit systems and well-designed streets for which Japan is famous. Cities are best when they’re built for continuous occupancy, but tourism is seasonal. That means if you build a train system to handle peak tourism season, it’ll be underused for much of the year. But if you build a train system to handle the average number of riders in order to maintain profitability, it’ll be unusable when the tourists come. There’s no fully satisfactory solution to this problem.

擁擠外部性還會對日本著名的高效公共交通系統和精心設計的街道造成壓力。城市最理想的狀態是持續有人居住,但觀光是季節性的。這意味著,如果你建造一個能應付旅遊旺季的交通系統,在其他時間它將被閒置。但如果為了維持盈利而按平均乘客數量建造,當遊客來臨時,系統又將無法負荷。對於這個問題,並沒有完全令人滿意的解決方案。

And all that is before we take tourist behavior into account. In Chicago or Philadelphia, a tourist is probably going to be less rowdy and more law-abiding than the locals; in Japan, it’s just the opposite. Tourists don’t acculturate as much as immigrants do; they haven’t been in a country long enough to know how to follow the local rules and norms.

而且,這還不包括觀光客的行為。在芝加哥或費城,遊客可能比當地人更加守規矩、更遵紀守法;但在日本,情況恰恰相反。遊客不像移民那樣能夠融入當地文化;他們在一個國家停留的時間不夠長,無法了解當地的規則和習俗。

As a result, you now see huge numbers of videos of tourists acting up in Japan. I’ll post just a few:

因此,現在你可以看到大量遊客在日本出醜的影片。我將分享幾個:

And of course there are all the high-profile cases of streamers going to Japan and behaving badly in order to get attention online.

當然,也有許多高調的網紅前往日本,為了網路上的關注而故意表現得很差。

This isn’t as bad as murder or theft, obviously, but it does degrade the character of a nation like Japan. The anti-foreigner anger fueling the rise of Sanseito isn’t just because of immigrants; it’s partly because of tourists.

這當然不像謀殺或竊盜那麼嚴重,但確實會降低像日本這樣一個國家的形象。三勢黨崛起的反外國人情緒,不僅僅是因為移民;部分原因也來自於觀光客。

And the real crux of the tourism problem is this: When does it end? If this were a temporary issue, it would be bearable. But Japanese people can look at places like Venice and realize that tourism isn’t a temporary phenomenon; if nothing ever gets done, the country’s Tier 1 cities are going to be theme parks for all eternity.

觀光問題的核心在於:什麼時候是個盡頭?如果這只是暫時現象,那還能忍受。但日本人可以看看像威尼斯這樣的地方,就會意識到觀光並非短暫現象;如果不採取任何措施,國家的一級城市將永遠淪為主題公園。

Cutting down on overtourism would probably go a long way toward defusing Japan’s rising anti-foreign backlash. One simple policy would be for each city to levy a surcharge on hotel reservations made to foreign bank accounts. This would allow Tokyo and Kyoto to selectively raise the price of tourism to those hot destinations, pushing international travelers out to cheaper smaller cities and rural areas where their dollars are more needed. (It would also raise revenue for the government.)

減少過度旅遊可能有助於緩解日本日益增長的排外情緒。一個簡單的政策是,每個城市對以外國銀行帳戶預訂的酒店收取附加費。這將使東京和京都能有選擇性地提高熱門景點的旅遊成本,將國際旅客引導至更便宜的小城市和鄉村地區,那些地方更需要他們的美元。(這也能為政府增加收入。)

I think it would also help to arrest and punish of tourists who engage in criminally disruptive behavior. All Singapore had to do in order to get a reputation as a country that brooks no nonsense from tourists was to cane one guy for vandalism.

我認為逮捕並懲罰那些從事犯罪性擾亂行為的觀光客也會有幫助。新加坡只需要因為對一個因破壞公物而施以鞭刑的案例,就成功建立了不容忍遊客惡劣行為的國家形象。

Japan needs immigrant selectivity and active assimilation policy

日本需要有選擇性的移民政策和積極的同化政策

But cutting down on overtourism won’t solve the whole problem. Japan is simply not traditionally a nation of immigrants, and so learning how to deal with mass immigration is going to be a bumpier road than it was for the U.S. (And note that even for the U.S., it was often bumpy indeed…like now.)

但單純減少過度旅遊並不能解決整個問題。日本本來就不是一個傳統的移民國家,因此學習如何應對大規模移民將比美國更加艱難。(請注意,即便對美國來說,這個過程也常常並不平順——就像現在一樣。)

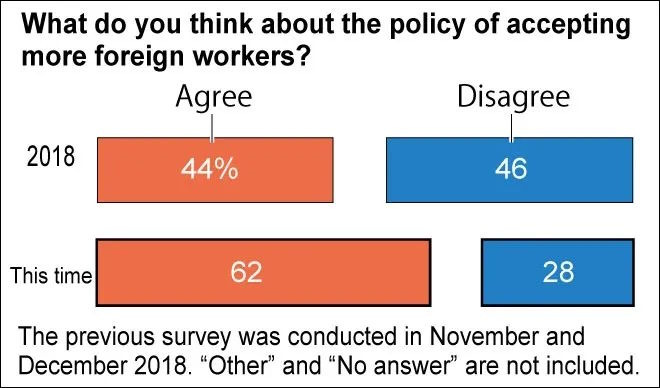

Fortunately, Japan has some time. Anger at immigration has not yet come to dominate the national mood. Polls still show very favorable sentiment toward immigration. Here’s one from 2024, showing that pro-immigration sentiment has actually increased in recent years:

幸運的是,日本還有一些時間。對移民的憤怒尚未主導國家的整體氛圍。民調仍然顯示對移民持非常正面的情緒。以下是 2024 年的一份民調,顯示近年來支持移民的情緒實際上已經增加:

So the Sanseito backlash is still among a minority of Japanese people. But as we’ve seen with MAGA in the U.S., a minority of very dedicated, angry people can create a lot of trouble for a country.

所以目前 Sanseito 反移民運動仍然只是日本少數人的立場。但正如我們在美國看到 MAGA 運動一樣,即使是少數非常堅定且憤怒的人,也可能為一個國家帶來巨大的麻煩。

Japan’s ruling LDP is going to have to act. Traditionally, the LDP wins by being ideologically flexible and addressing the concerns of the electorate as they arise. It needs to do so again, so that the immigration problem doesn’t end up causing the rise of a Trump-like figure.

日本執政的自民黨將不得不採取行動。傳統上,自民黨的勝選秘訣在於保持意識形態的靈活性,並及時回應選民的訴求。這次也需要如此,以防止移民問題最終導致類似川普的政治人物崛起。

The first thing Japan’s leaders should do is to improve immigrant selectivity. The country has struggled to attract skilled immigrants en masse, due to low entry-level salaries and the language barrier. But the government should redouble its efforts — as the U.S. becomes a less attractive destination, Japan may emerge as an attractive alternative. In fact, this is one of the main topics of my recent book, Weeb Economy. (Sadly, the book is only available in Japanese.)

日本的領導者首要應該做的是提高移民的選擇性。由於入門級薪資低且有語言障礙,該國一直難以大規模吸引技術移民。但政府應該加倍努力——隨著美國變得不那麼吸引人,日本可能會成為一個吸引人的替代選擇。事實上,這是我最近出版的《網路經濟》一書中的主要議題之一。(可惜的是,這本書目前僅有日文版本。)

But skills aren’t the only kind of selectivity. Japan can selectively target immigration from countries that are culturally and religiously similar to itself — places like Vietnam and Thailand. It can try to attract political dissidents from China, and refugees from the Hong Kong crackdown.

但篩選不僅僅是技能的問題。日本可以有選擇性地從文化和宗教上與自己相似的國家吸引移民,比如越南和泰國。它還可以試圖吸引來自中國的政治異議人士,以及來自香港鎮壓的難民。

The second thing Japan should do is to improve assimilation policy. Japan’s system for dealing with immigrants was built on the assumption that they were temporary expats or guest workers who would eventually go back to their home countries. The children of foreigners often attend their own schools, and some of them end up with limited Japanese ability.

日本應該做的第二件事是改善同化政策。日本處理移民的系統是基於他們是臨時外派人員或客工,最終會返回原來的國家這一假設。外國人的孩子通常就讀於自己的學校,有些人最終日語能力有限。

This has to end. Kids born to foreigners in Japan should be sent to Japanese schools, so that they learn the language, and — even more importantly — so they acculturate to the norms of the Japanese kids around them. The only kids who go to international school should be those whose parents intend to leave soon.

這種情況必須結束。在日本出生的外國人子女應該被送到日本學校,讓他們學習語言,更重要的是融入周圍日本孩子的文化規範。只有那些父母打算很快離開的孩子才應該去國際學校。

It’s also worth looking at the idea of residential dispersal, in order to prevent the formation of ethnic enclaves that resist Japanese culture. Singapore does this by enforcing racial diversity within each apartment block. Japan probably doesn’t have the ability or the will to go that far, but Sanseito’s idea of capping the foreign percentage in each municipality could actually be on to something. Such a cap is unworkable, of course. But the government could certainly offer vouchers for foreigners to live in neighborhoods where they’re scarce, thus helping to speed up assimilation. Japan could also act to break up poor immigrant enclaves, like Denmark does.

值得研究的是居住地分散的概念,以防止形成對日本文化有抵抗力的族裔聚落。新加坡通過在每個公寓樓中強制實施種族多樣性來實現這一點。日本可能沒有能力或意願走到如此極端,但三成黨關於限制每個自治體外國人比例的想法可能確實有一定道理。當然,這種限制是不可行的。但政府 certainly 可以為外國人提供在人數稀少的社區生活的補貼,從而幫助加速同化。日本還可以效仿丹麥,打破貧困移民聚落。

One other idea I had was for the Japanese government to provide free intensive Japanese language classes for all immigrants who intend to settle in Japan. These classes would also function as networking events; Japanese speakers and conversation partners could be invited to the classes. This could be matched by industry — Japanese engineers could come meet immigrant engineers, and so on. This would help immigrants build up their native connections in Japan, and to more quickly become embedded into Japanese society.

我另一個想法是由日本政府為所有打算在日本定居的移民提供免費的密集日語課程。這些課程也可以作為交流活動;可以邀請日語母語者和對話夥伴參與課程。這可以按行業進行配對——例如日本工程師可以與移民工程師見面等。這將有助於移民在日本建立本地社交網絡,並更快地融入日本社會。

Anyway, unless Japan decides to reverse course and shut out immigrants — which would have negative consequences for its economy — it’s going to have to learn to assimilate the ones who do come and settle down. European countries are already trending strongly in this direction; Japan doesn’t have to copy their policies, but it can certainly learn some lessons from observing the Europeans’ efforts.

無論如何,除非日本決定改變方向並拒絕移民——這將對其經濟產生負面影響——否則它將不得不學習如何融合那些來到並定居下來的移民。歐洲國家已經在朝著這個方向強烈發展;日本不必複製他們的政策,但可以從觀察歐洲人的努力中學習一些經驗。

In any case, I don’t expect Trump-style policies to prevail in Japan. Sanseito is unlikely to become Japan’s main opposition party, much less take over the country. But Japan’s leaders should display their traditional nimbleness, and act to defuse the main source of anger behind Sanseito’s rise, before the issues get even harder to handle.

無論如何,我不指望特朗普式的政策在日本佔上風。三世黨不太可能成為日本的主要反對黨,更不用說接管國家了。但日本的領導人應該表現出他們傳統的靈活性,並採取行動消除三世黨崛起背後的主要憤怒源頭,在問題變得更難處理之前。

In fact, there’s a long and storied history of cultural transmission and retransmission back and forth between the U.S. and Japan. The best book about this subject is W. David Marx’s Ametora, which deals with men’s fashion.

事實上,美國和日本之間存在著長久且曲折的文化傳播與再傳播歷史。關於這個主題最好的書是 W. David Marx 的《Ametora》,內容是關於男性時尚。

The name technically means the Political Participation Party, though I think “Populist Party” might be a better translation. It’s also a pun on the word “agree”, so when you hear it, it sounds like “the party you agree with”. Clever!

這個名稱技術上是指「政治參與黨」,不過我認為「民粹黨」可能是更好的翻譯。這同時也是個文字遊戲,暗指「你同意的政黨」。真的很聰明!

Eventually, when the country gets rich enough that moving out is a bad economic proposition, emigration trails off.

最終,當一個國家變得夠富有,以致於遷移不再具有經濟誘因時,移民潮就會逐漸消退。

Traditionally, Japanese graveyards are very compact, because Japan cremates everyone. Religious Muslims refuse to cremate bodies, requiring much more land for graves; in a country as space-constrained as Japan, this can become a major problem very quickly!

傳統上,日本的墓地都非常緊湊,因為日本人通常會火化遺體。虔誠的穆斯林拒絕火化,需要更多的土地來安葬,在像日本這樣寸土寸金的國家,這很快就可能成為一個重大問題!

Subscribe to Noahpinion 訂閱 Noahpinion

由 Noah Smith 著 · 數萬名付費訂閱者

經濟學與其他有趣的主題