Providing Quality Early Childhood Education and Care RESULTS FROM THE STARTING STRONG SURVEY 2018 提供优质的幼儿教育和护理 2018 年 STARTING STRONG 调查结果

TALIS 达利斯

Providing Quality Early Childhood Education and Care 提供优质的幼儿教育和护理

RESULTS FROM THE STARTING STRONG SURVEY 2018 2018 年 STARTING STRONG 调查结果

This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. 这项工作由经合组织秘书长负责出版。本文所表达的观点和采用的论点并不一定反映经合组织成员国的官方观点。

This document, as well as any data and any map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. 本文件以及此处包含的任何数据和任何地图均不影响任何领土的地位或主权、国际边界和边界的划分以及任何领土、城市或地区的名称。

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. 以色列的统计数据由以色列相关当局提供并由其负责。经合组织使用此类数据并不影响戈兰高地、东耶路撒冷和以色列在约旦河西岸定居点根据国际法条款的地位。

For many children, early childhood education and care (ECEC) is their first experience with other children and adults, away from their families. The promises of this experience are multiple. At this time of rapid brain development, children can play, learn new things and develop a range of skills and abilities. They can acquire a joy of learning, and they can make their first friends. Participation in ECEC also offers opportunities to detect and respond to children’s individual needs and to help all children to develop, building on their strengths. 对于许多儿童来说,幼儿教育和护理 (ECEC) 是他们第一次远离家人与其他儿童和成人相处。这种体验的前景是多方面的。在这个大脑快速发育的时期,孩子们可以玩耍、学习新事物并发展一系列技能和能力。他们可以获得学习的乐趣,他们可以结交他们的第一批朋友。参与 ECEC 还提供了发现和响应儿童个人需求的机会,并帮助所有儿童在他们的长处的基础上发展。

Thanks to extensive research and studies, we know that high-quality ECEC can turn these promises into reality. Research shows that a major contributor to children’s learning, development and well-being is the quality of the interactions children experience daily with staff and other children in ECEC centres (these interactions are known as process aspects of quality). Research also identifies several factors that can influence the quality of these interactions, from ECEC staff and the extent to which they are educated, trained and motivated to work with children, to elements of the classroom/playroom environment, such as the number of children and staff and the mechanisms for monitoring ECEC settings (these factors are known as structural aspects of quality). 得益于广泛的研究和研究,我们知道高质量的 ECEC 可以将这些承诺变为现实。研究表明,儿童学习、发展和福祉的一个主要因素是儿童每天与 ECEC 中心的工作人员和其他儿童的互动质量(这些互动被称为质量的过程方面)。研究还确定了几个可能影响这些互动质量的因素,从 ECEC 工作人员和他们接受教育、培训和激励与儿童一起工作的程度,到教室/游戏室环境的要素,例如儿童和工作人员的数量以及监控 ECEC 设置的机制(这些因素被称为质量的结构方面)。

But while research suggests that the education we receive in early childhood matters most for our lives, ECEC is the sector of education we know least about. We take it for granted that all children attend school, and school is paid for by the public purse in virtually every OECD country. But in the first years of life, enrolment varies greatly across countries, and some countries ask the youngest children to pay the highest fees, while they make university tuition-free. We have a clear picture of what children learn in school, as well as who their teachers are, what they do, how they are paid, and how they were educated. In contrast, the provision of ECEC is often fragmented, poorly regulated and patchy. 但是,虽然研究表明我们在幼儿时期接受的教育对我们的生活最重要,但 ECEC 是我们了解最少的教育部门。我们理所当然地认为所有儿童都上学,而几乎每个经合组织国家的学费都是由公共钱包支付的。但在生命的最初几年,各国的入学率差异很大,一些国家要求最小的孩子支付最高的费用,而他们却免下大学学费。我们清楚地了解孩子们在学校学习什么,以及他们的老师是谁,他们做什么,他们如何获得报酬,以及他们是如何接受教育的。相比之下,幼儿保育和教育的提供往往是分散的、监管不力的和零散的。

That is the gap the OECD Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS Starting Strong) seeks to fill. It is the first international survey that focuses on the workforce in ECEC. It reveals key characteristics of the ECEC workforce, the practices they use with children, their beliefs about children’s development and their views on the profession and on the ECEC sector. TALIS Starting Strong was designed to approximate quality through questions to staff and leaders of ECEC centres on major elements that, according to research, influence children’s learning, development and well-being. 这就是经合组织 (OECD) 的 Starting Strong 教学国际调查 (TALIS Starting Strong) 试图填补的空白。这是第一次关注 ECEC 劳动力的国际调查。它揭示了 ECEC 劳动力的主要特征、他们对儿童使用的做法、他们对儿童发展的信念以及他们对职业和 ECEC 部门的看法。TALIS Start Strong 旨在通过向 ECEC 中心的工作人员和领导提出问题来了解质量,根据研究,这些因素会影响儿童的学习、发展和福祉。

One of the most important findings is the relationship between pre-service and in-service education and training of staff, as well as their working conditions, and the practices staff use with children and parents. However, training specifically to work with children is not universal, and participation in professional development, while common, is not equal among staff. These findings point to the need for policies to better prepare and support staff in their daily activities and practices with children. 最重要的发现之一是工作人员的职前和在职教育和培训之间的关系,以及他们的工作条件,以及工作人员对儿童和父母使用的做法。然而,专门针对儿童工作的培训并不普遍,参与专业发展虽然普遍,但员工之间并不平等。这些发现表明,需要制定政策来更好地准备和支持工作人员的日常活动和与儿童相关的实践。

TALIS Starting Strong also shows great variation within countries in the factors related to the quality of interactions between staff and children. For instance, there are large variations within countries in the share of highly educated staff per centre. In centres with many children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes, enhanced services can help put all children on a level playing field, but few countries systematically provide such services. At the same time, there is little evidence that the allocation of human resources to TALIS Start Strong 还表明,各国内部在与教职员工和儿童之间的互动质量相关的因素方面存在很大差异。例如,每个中心受过高等教育的工作人员比例在国家内部存在很大差异。在有许多儿童来自社会经济弱势家庭的中心,加强服务可以帮助所有儿童处于公平的竞争环境中,但很少有国家系统地提供此类服务。与此同时,几乎没有证据表明将人力资源分配给

ECEC centres increases inequalities between centres with different geographical locations and child characteristics. 幼儿保育和教育中心加剧了具有不同地理位置和儿童特征的中心之间的不平等。

Finally, TALIS Starting Strong asks staff and leaders a number of key questions to learn about the major difficulties they face in their jobs. Staff are asked about the barriers they face to participation in professional development and their priorities for spending reallocation, and leaders are asked about the barriers to their effectiveness. Both staff and leaders are asked about their sources of stress. Answers to these questions converge to highlight a number of bottlenecks in the ECEC sector. Some of these bottlenecks are common to all participating countries. This is the case for staff absences and staff shortages, which appear as barriers to leaders’ effectiveness and to staff’s participation in professional development. According to staff, support to work with children with special needs appears as a top priority for both professional development and reallocation of spending. Reducing group size is another top priority for staff for reallocation of spending, while too many children in the group is a top source of stress. These findings point to the need for policy changes that governments are aware of, but such changes would involve trade-offs in situations of tight budget constraints. TALIS Starting Strong offers guidance that can help each participating country to identify priorities for policy change. 最后,TALIS Starting Strong 向员工和领导者提出了一些关键问题,以了解他们在工作中面临的主要困难。员工被问及他们在参与专业发展方面面临的障碍以及他们重新分配支出的优先事项,并询问领导者他们效率的障碍。员工和领导者都会被问及他们的压力来源。这些问题的答案汇集在一起,突出了 ECEC 领域的一些瓶颈。其中一些瓶颈是所有参与国共有的。员工缺勤和员工短缺就是这种情况,这似乎是领导者效率和员工参与专业发展的障碍。据工作人员称,支持与有特殊需要的儿童一起工作似乎是专业发展和重新分配支出的首要任务。减少小组规模是员工重新分配支出的另一个首要任务,而小组中太多的孩子是压力的首要来源。这些发现表明,政府需要改变政策,但这种改变将涉及在预算紧张的情况下进行权衡。“助教教育服务”提供指导,帮助每个参与国确定政策变革的重点。

In all countries, people care about children, especially young children. However, in most countries participating in the Survey, staff do not feel highly valued by society. Why do those who devote their time to do the best for children not feel more highly valued? Attracting and retaining a high-quality workforce is a challenge for all participating countries. 在所有国家,人们都关心儿童,尤其是幼儿。然而,在参与调查的大多数国家/地区,员工并不觉得自己受到社会的高度重视。为什么那些花时间为孩子做到最好的人不觉得自己更受重视呢?吸引和留住高素质劳动力是所有参与国面临的挑战。

In many countries, governments have done a lot to develop access to ECEC. But access is not enough; ECEC policies need to focus more on quality. TALIS Starting Strong reminds us that children’s early years are the foundation of their lives as students, adults and citizens. In the same way, it reminds us that ECEC policies need to be fully integrated with other policies that support economic growth and social inclusion. For children’s learning, development and well-being, every year counts. 在许多国家,政府为发展 ECEC 的普及做了大量工作。但访问是不够的;ECEC 政策需要更加注重质量。TALIS Starting Strong 提醒我们,儿童的早期生活是他们作为学生、成人和公民生活的基础。同样,它提醒我们,ECEC 政策需要与支持经济增长和社会包容的其他政策充分结合。对于儿童的学习、发展和福祉,每一年都很重要。

Andreas Schleicher, 安德烈亚斯·施莱歇尔,

Director for Education and Skills 教育和技能总监

Acknowledgements 确认

The OECD Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS Starting Strong) is the outcome of a collaboration among the participating countries, the OECD Secretariat and the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) with its international consortium partners RAND Europe and Statistics Canada. 经合组织 Start Strong Teaching and Learning 国际调查 (TALIS Starting Strong) 是参与国、经合组织秘书处和国际教育成就评估协会 (IEA) 与其国际财团合作伙伴兰德欧洲和加拿大统计局合作的结果。

The development of this report was guided by Andreas Schleicher and Yuri Belfali and led by Stéphanie Jamet. The report built on preparatory work led by Arno Engel and was drafted by the OECD Early Childhood Education and Care team with co-ordination from Elizabeth Shuey. Stéphanie Jamet was the lead author of Chapter 1 and wrote Chapter 2 with Clara Barata (external consultant); Elizabeth Shuey was the lead author of Chapter 3; Arno Engel wrote Chapter 4 with Joana Cadima (external consultant); and Chapter 5 was co-authored by Victoria Liberatore and Théo Reybard. Statistical analyses and outputs were co-ordinated by Elisa Duarte and Francois Keslair with assistance from Luisa Kurth and Lorenz Meister. Victoria Liberatore was the lead author of Annex A. The initial survey development and implementation phase was led by Miho Taguma. 本报告的编写由 Andreas Schleicher 和 Yuri Belfali 指导,并由 Stéphanie Jamet 领导。该报告以 Arno Engel 领导的准备工作为基础,由经合组织幼儿教育和护理团队在 Elizabeth Shuey 的协调下起草。Stéphanie Jamet 是第 1 章的主要作者,并与 Clara Barata(外部顾问)一起撰写了第 2 章;Elizabeth Shuey 是第 3 章的主要作者;Arno Engel 与 Joana Cadima(外部顾问)一起撰写了第 4 章;第 5 章由 Victoria Liberatore 和 Théo Reybard 合著。统计分析和输出由 Elisa Duarte 和 Francois Keslair 协调,Luisa Kurth 和 Lorenz Meister 提供协助。Victoria Liberatore 是附录 A 的主要作者。最初的调查开发和实施阶段由 Miho Taguma 领导。

Mernie Graziotin supported report preparation, production, project co-ordination and communications with additional support from Leslie Greenhow. Cassandra Davis and Henri Pearson also provided support for report production and communications. Susan Copeland was the main editor of the report and Eleonore Morena was responsible for the layout. Additional editorial assistance was provided by Natalie Potter. The authors wish to thank members of the OECD Extended Early Childhood Education and Care Network on TALIS Starting Strong, National Project Managers, the international consortium, the Questionnaire Expert Group and Technical Advisory Group who all provided valuable feedback and input at various stages of the data and report production. Mernie Graziotin 在 Leslie Greenhow 的额外支持下支持报告准备、制作、项目协调和沟通。Cassandra Davis 和 Henri Pearson 还为报表制作和通信提供了支持。Susan Copeland 是报告的主要编辑,Eleonore Morena 负责布局。Natalie Potter 提供了额外的编辑帮助。作者要感谢经合组织 (OECD) 在 TALIS Start Strong 上扩展幼儿教育和护理网络的成员、国家项目经理、国际联盟、问卷专家组和技术咨询组,他们在数据和报告制作的各个阶段都提供了宝贵的反馈和意见。

The development of the report was steered by the OECD Extended ECEC Network, chaired by Bernhard Kalicki (Germany). 该报告的编写由经合组织 ECEC 扩展网络指导,由 Bernhard Kalicki(德国)担任主席。

The technical implementation of TALIS Starting Strong was contracted out to an international consortium of institutions and experts directed by Juliane Hencke (IEA) and co-directed by Steffen Knoll (IEA) with support from Alena Becker, Viktoria Böhm, Juliane Kobelt, Ann-Kristin Koop, Agnes Stancel-Piątak, David Ebbs and Jean Dumais (sampling referee). Design and development of the questionnaires were led by a Questionnaire Expert Group led by Julie Belanger (RAND Europe), and an independent Technical Advisory Group provided guidance on the technical aspects of the survey. We would like to gratefully acknowledge the contribution to TALIS Starting Strong of the late Fons van de Vijver, who was Chair of the Technical Advisory Group. TALIS Starting Strong 的技术实施外包给一个由机构和专家组成的国际联盟,该联盟由 Juliane Hencke (IEA) 指导,由 Steffen Knoll (IEA) 共同指导,并得到了 Alena Becker、Viktoria Böhm、Juliane Kobelt、Ann-Kristin Koop、Agnes Stancel-Piątak、David Ebbs 和 Jean Dumais(抽样裁判)的支持。问卷的设计和开发由 Julie Belanger (RAND Europe) 领导的问卷专家组领导,独立的技术咨询小组就调查的技术方面提供指导。我们衷心感谢已故技术咨询小组主席 Fons van de Vijver 对 TALIS Starting Strong 的贡献。

Annex E of this report lists the various institutions and individuals that contributed to TALIS Starting Strong. 本报告的附件 E 列出了为 TALIS Strong Start Strong 做出贡献的各种机构和个人。

Table of contents 目录

Foreword … 3 前言。。。3

Acknowledgements … 5 确认。。。5

Reader’s guide … 12 读者指南 ...12

Executive summary … 19 摘要。。。19

What is TALIS Starting Strong? … 22 什么是 TALIS Beginning Strong?…22

1 Policy implications of the 2018 Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey … 26 1 2018 年“开始强大的教学与学习”国际调查的政策影响......26

Children in early childhood education and care centres … 28 幼儿教育和看护中心的儿童......28

Ensuring quality of early childhood education and care systems: Policy implications … 31 确保幼儿教育和保育系统的质量:政策影响 ...31

References … 50 引用。。。50

2 Interactions between children, staff and parents/guardians in early childhood education and care centres … 51 2 幼儿教育和看护中心的儿童、工作人员和家长/监护人之间的互动 ...51

Introduction … 53 介绍。。。53

Insights from research and policy evidence … 53 来自研究和政策证据的见解......53

Supporting children’s learning, development and well-being through practices … 56 通过实践支持儿童的学习、发展和福祉......56

Engaging with parents and guardians … 68 与父母和监护人互动......68

Process quality in TALIS Starting Strong … 72 TALIS 的流程质量 Starting Strong ...72

Professional beliefs … 75 专业信念 ...75

The organisation of activities with a group of children … 79 与一群孩子一起组织活动......79

Equity and diversity: beliefs and practices … 84 公平和多样性:信念和实践 ...84

Conclusion and policy implications … 92 结论和政策影响 ...92

References … 93 引用。。。93

3 Teachers, assistants and leaders and the quality of early childhood education and care … 98 3 教师、助理和领导以及幼儿教育和护理的质量......98

Introduction … 100 介绍。。。100

Findings from the literature on the early childhood education and care workforce and process quality … 100 关于幼儿教育和护理劳动力和过程质量的文献结果......100

Workforce composition and pre-service training … 102 员工构成和职前培训 ...102

Workforce professional development: Needs and content, barriers and support … 110 劳动力专业发展:需求和内容、障碍和支持......110

Working conditions for early childhood education and care staff … 117 幼儿教育和护理人员的工作条件......117

The relationship between process quality, professional development and working conditions … 123 过程质量、职业发展和工作条件之间的关系......123

Leaders in early childhood education and care centres … 125 幼儿教育和护理中心的领导者......125

Equity focus: Staff in target groups … 129 公平重点:目标群体中的员工 ...129

Conclusion and policy implications … 129 结论和政策影响 ...129

References … 131 引用。。。131

4 Structural features of early childhood education and care centres and quality … 135 4 幼儿教育和保育中心的结构特征和质量135

Introduction … 137 介绍。。。137

Insights from research and policy evidence … 137 来自研究和政策证据的见解......137

The place of early childhood education and care centres … 140 幼儿教育和护理中心的所在地 ...140

Characteristics and number of children in early childhood education and care centres … 145 幼儿教育和看护中心的儿童特征和数量 ...145

Equity of early childhood education and care centres … 170 幼儿教育和护理中心的公平性 ...170

Conclusion and policy implications … 174 结论和政策影响 ...174

References … 175 引用。。。175

5 Governance, funding and the quality of early childhood education and care … 181 5 幼儿教育和保育的治理、资金和质量 ...181

Introduction … 183 介绍。。。183

Insights from research and policy evidence … 184 来自研究和政策证据的见解......184

Funding of the ECEC sector … 186 为 ECEC 部门提供资金 ...186

Governance of the ECEC sector … 193 ECEC 部门的治理 ...193

Characteristics of publicly and privately managed ECEC centres … 204 公共和私人管理的幼儿保育和教育中心的特点 ...204

The relationship between aspects of governance and funding and process quality … 210 治理和资金方面与流程质量之间的关系......210

Governance and equity … 212 治理和公平 ...212

Conclusion and policy implications … 213 结论和政策影响 ...213

References … 215 引用。。。215

Annex A. Country profiles of early childhood education and care systems … 218 附件 A. 幼儿教育和保育系统的国家概况 ...218

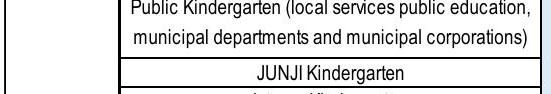

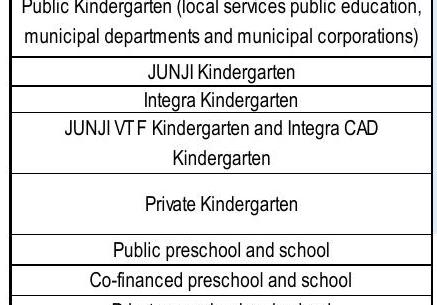

Chile … 219 智利。。。219

Denmark … 223 丹麦。。。223

Germany … 226 德国。。。226

Iceland … 231 冰岛。。。231

Israel … 234 以色列。。。234

Japan … 237 日本。。。237

Korea … 240 韩国。。。240

Norway … 243 挪威。。。243

Turkey … 246 土耳其。。。246

References … 250 引用。。。250

Annex B. Technical notes on sampling procedures, response rates and adjudication for TALIS Starting Strong 2018 … 251 附件 B. 关于 TALIS 2018 年强劲启动的抽样程序、回复率和裁决的技术说明......251

Sampling procedures and response rates … 251 抽样程序和响应率 ...251

Sample size requirements … 252 样本量要求 ...252

Adjudication process … 252 评审过程 ...252

Notes regarding use and interpretation of the data … 254 关于数据使用和解释的说明 ...254

Reference … 256 参考。。。256

Note … 256 注意。。。256

Annex C. Technical notes on analyses in this report … 257 附件 C. 关于本报告分析的技术说明......257

Use of staff and centre weights … 257 使用杆和中心配重 ...257

Standard errors and significance tests … 257 标准误差和显著性检验 ...257

Use of complex variables … 258 使用复杂变量 ...258

Assessing process quality in TALIS Starting Strong … 259 评估 TALIS 的流程质量 Start Strong ...259

Statistics based on regressions … 261 基于回归的统计数据 ...261

Pearson correlation coefficient … 263 皮尔逊相关系数 ...263

International averages … 263 国际平均水平 ...263

Reference … 263 参考。。。263

Annex D. List of tables available on line … 264 附件 D. 网上提供的表格列表......264

Annex E. List of TALIS Starting Strong 2018 contributors … 268 附件 E. 2018 年 TALIS 强劲贡献者名单 ...268

List of National TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Contributors … 269 2018 年全国 TALIS 起步强劲贡献者名单 ...269

OECD Secretariat … 271 经合组织秘书处 ...271

TALIS Starting Strong expert groups … 272 TALIS Starting Strong 专家组 ...272

TALIS Starting Strong Consortium … 273 达利信成立强大联盟 ...273

Tables 表

Table 1.1. Data overview: Staff’s practices and working conditions … 46 表 1.1.数据概述:员工的做法和工作条件 ...46

Table 1.2. Data overview: Equity, governance and funding … 48 表 1.2.数据概述:公平、治理和融资 ...48

Table 2.1. Top three practices to support literacy, numeracy and language development … 60 表 2.1.支持识字、算术和语言发展的三大做法......60

Table 2.2. Top three practices to support socio-emotional development … 61 表 2.2.支持社会情感发展的三大做法......61

Table 2.3. Top three practices for behavioural support … 62 表 2.3.行为支持的三大做法......62

Table 2.4. Top three adaptive practices … 63 表 2.4.三大适应性实践......63

Table 2.5. Top three practices used by staff in a concrete daily work situation to support prosocial behaviour … 65 表 2.5.员工在具体的日常工作情境中用来支持亲社会行为的前三种做法......65

Table 2.6. Top three practices used by staff in a concrete daily work situation to support child-directed play … 66 表 2.6.员工在具体的日常工作情境中支持儿童导向游戏的三大做法......66

Table 2.7. Indicators of process quality developed in TALIS Starting Strong … 74 表 2.7.TALIS 开发的流程质量指标 Starting Strong ...74

Table 2.8. Relationship between and within dimensions of process quality … 75 表 2.8.过程质量维度之间和内部的关系 ...75

Table 2.9. Top three staff beliefs about skills and abilities that will prepare children for life in the future … 76 表 2.9.员工对技能和能力的三大信念将为孩子们的未来生活做好准备......76

Table 3.1. Top three professional development needs … 112 表 3.1.三大专业发展需求 ...112

Table 3.2. Top three content areas covered by professional development in the past year … 113 表 3.2.过去一年专业发展涵盖的前三个内容领域...113

Table 4.1. Context of countries’ early childhood education and care settings … 148 表 4.1.各国幼儿教育和照料环境的背景......148

Table 4.2. Relationship between process quality practices and centre characteristics … 163 表 4.2.过程质量实践与中心特征之间的关系 ...163

Table 4.3. Difference in percentage of centres with 11%11 \% of more children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes, by centre characteristics … 171 表 4.3.按中心特征划分,来自社会经济弱势家庭的儿童较多的中心 11%11 \% 百分比的差异 ...171

Table 5.1. Top three staff spending priorities … 192 表 5.1.三大员工支出优先事项 ...192

Table 5.2. Highest administrative authorities in charge of ECEC settings … 193 表 5.2.负责 ECEC 设置的最高行政机构 ...193

Table 5.3. Regulations and standards for early childhood settings … 195 表 5.3.幼儿环境的规定和标准......195

Table 5.4. Top three barriers to leaders’ effectiveness … 200 表 5.4.领导者有效性的三大障碍......200

Table 5.5. Top three sources of stress for ECEC centre leaders … 201 表 5.5.ECEC 中心领导的三大压力来源......201

Table 5.6. Summary of findings on differences between public and private ECEC centres … 205 表 5.6.公共和私营幼儿保育和教育中心差异的调查结果摘要 ...205

Table A A.1. Overview of early childhood education and care system-level indicators in Chile … 222 表 A A.1.智利幼儿教育和照料系统层面指标概述 222

Table A A.2. Overview of early childhood education and care system-level indicators in Denmark … 225 表 A A.2.丹麦幼儿教育和照料系统层面指标概述 225

Table A A.3. Overview of early childhood education and care system-level indicators in Germany … 229 表 A A.3.德国幼儿教育和照料系统层面指标概览 ...229

Table A A.4. Overview of early childhood education and care system-level indicators in Iceland … 233 表 A A.4.冰岛 幼儿教育和照料系统层面指标概述 ...233

Table A A.5. Overview of early childhood education and care system-level indicators in Israel … 236 表 A A.5.以色列幼儿教育和照料系统层面指标概述 236

Table A A.6. Overview of early childhood education and care system-level indicators in Japan … 239 表 A A.6.日本幼儿教育和照料系统层面指标概述 ...239

Table A A.7. Overview of early childhood education and care system-level indicators in Korea … 242 表 A A.7.韩国幼儿教育和照料系统层面指标概述 ...242

Table A A.8. Overview of early childhood education and care system-level indicators in Norway … 245 表 A A.8.挪威幼儿教育和照料系统层面指标概述 245

Table A A.9. Overview of early childhood education and care system-level indicators in Turkey … 249 表 A A.9.土耳其幼儿教育和照育系统层面指标概述 ...249

Table A B.1. Adjudication rules for centre or centre leader data in TALIS Starting Strong 2018 … 253 表 A B.1.TALIS 中中心或中心领导者数据的裁定规则 2018 年强劲开始 ...253

Table A B.2. Adjudication rules for staff data in TALIS Starting Strong 2018 … 253 表 A B.2.TALIS 2018 年强势起步 中员工数据的裁定规则 ...253

Table A B.3. Services for children under age 3: Centre leader participation rates and recommended ratings … 255 表 A B.3.为 3 岁以下儿童提供的服务:中心领导参与率和推荐评级 ...255

Table A B.4. Services for children under age 3: Staff participation rates and recommended ratings … 255 表 A B.4.为 3 岁以下儿童提供的服务:员工参与率和推荐评级 ...255

Table A B.5. Pre-primary education (ISCED level 02): Centre leader participation rates and recommended ratings … 256 表 A B.5.学前教育 (《国际教育标准分类法》02 级):中心领导参与率和推荐评级 ...256

Table A B.6. Pre-primary education (ISCED level 02): Staff participation rates and recommended ratings … 256 表 A B.6.学前教育 (《国际教育标准分类法》02 级):工作人员参与率和推荐评级 ...256

Figures 数字

Figure 1.1. Framework for the analysis of the quality of ECEC environments in TALIS Starting Strong 28 图 1.1.TALIS 中 ECEC 环境质量分析框架 Starting Strong 28

Figure 1.2. Enrolment in early childhood education and care, 201729 图 1.2.幼儿教育和保育入学率,201729

Figure 2.1. Framework for the analysis of practices affecting children’s learning, development and well-being in TALIS Starting Strong 图 2.1.影响 TALIS 儿童学习、发展和福祉的实践分析框架 Start Strong

Figure 2.2. Practices facilitating language, literacy, numeracy and socio-emotional development 58 图 2.2.促进语言、识字、算术和社会情感发展的实践 58

Figure 2.3. Practices for group organisation and individual support to children 59 图 2.3.为儿童提供团体组织和个人支持的做法 59

Figure 2.4. Stated goals in the curriculum framework 59 图 2.4.课程框架中的既定目标 59

Figure 2.5. Gap in the use of practices facilitating numeracy and socio-emotional development 64 图 2.5.在利用促进计算能力和社会情感发展的实践方面的差距 64

Figure 2.6. Practices used by staff to facilitate engagement of parents or guardians 68 图 2.6.工作人员为促进家长或监护人参与而采取的做法 68

Figure 2.7. Activities provided by the centre to facilitate engagement of parents or guardians 69 图 2.7.中心为促进家长或监护人的参与而举办的活动 69

Figure 2.8. Inclusion of families in the curriculum framework 70 图 2.8.将家庭纳入课程框架 70

Figure 2.9. Opportunities for children’s participation in decisions 72 图 2.9.儿童参与决策的机会 72

Figure 2.10. Dimensions of process quality covered by TALIS Starting Strong 73 图 2.10.TALIS Starting Strong 73 涵盖的流程质量维度

Figure 2.11. Beliefs of leaders and staff about skills and abilities that will prepare children for life in the future 77 图 2.11.领导和员工对为儿童未来生活做好准备的技能和能力的信念 77

Figure 2.12. Relationship between beliefs on 21st century skills and practices facilitating socio-emotional development at the centre level 图 2.12.对 21 世纪技能和实践的信念之间的关系促进了中心层面的社会情感发展

Figure 2.13. Relationship between beliefs on foundational cognitive skills and practices to facilitate literacy and numeracy development at the centre level 79 图 2.13.对基本认知技能的信念与促进中心阶段识字和算术发展的实践之间的关系 79

Figure 2.14. Number of children and staff working with the same target group on the same day 80 图 2.14.在同一天与同一目标群体一起工作的儿童和工作人员人数 80

Figure 2.15. Average number of staff per ten children working with the same target group on the same day 82 图 2.15.在同一天与同一目标群体一起工作的每 10 名儿童的平均员工人数 82

Figure 2.16. Adapting practices to differences in the size of the group of children 84 图 2.16.根据儿童群体规模的差异调整做法 84

Figure 2.17. Group concentration of children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes 85 图 2.17.来自社会经济弱势家庭的儿童群体集中 85

Figure 2.18. Group concentration of children whose first language is different from the language(s) used in the centre 87 图 2.18.第一语言与中心使用的语言不同的儿童群体集中度 87

Figure 2.19. Group concentration of children with special needs 88 图 2.19.有特殊需要儿童的群体集中度 88

Figure 2.20. Adapting activities to differences in children’s cultural background 89 图 2.20.根据儿童文化背景的差异调整活动 89

Figure 2.21. Beliefs about multicultural and diversity approaches in the centres 90 图 2.21.对中心多元文化和多样性方法的信念 90

Figure 2.22. Multicultural and diversity approaches used in daily interactions with children 91 图 2.22.在与儿童的日常互动中使用的多元文化和多样性方法 91

Figure 3.1. The relationship between the workforce and process quality in TALIS Starting Strong 102 图 3.1.TALIS Starting Strong 102 中员工与流程质量之间的关系

Figure 3.2. Characteristics of early childhood education and care staff 103 图 3.2.幼儿教育和护理人员的特点 103

Figure 3.3. Educational attainment of staff and content of pre-service training 104 图 3.3.工作人员的教育程度和职前培训内容 104

Figure 3.4. Educational attainment of teachers and assistants and content of pre-service training 105 图 3.4.教师和助理的教育程度和职前培训的内容 105

Figure 3.5. Content of pre-service training to work with children 107 图 3.5.儿童工作岗前培训内容 107

Figure 3.6. Strength of association between staff use of adaptive practices and their training specifically to work with children 109 图 3.6.工作人员使用适应性实践与其专门针对儿童工作的培训之间的关联强度 109

Figure 3.7. Participation in professional development activities by pre-service educational attainment 111 图 3.7.按职前教育程度参加专业发展活动 111

Figure 3.8. Barriers to participation in professional development 114 图 3.8.参与专业发展的障碍 114

Figure 3.9. Support for participation in professional development 116 图 3.9.支持参与专业发展 116

Figure 3.10. Participation in professional development activities by support received 116 图 3.10.获得资助的参与专业发展活动 116

Figure 3.11. Staff contractual status and working hours 117 图 3.11.员工合同状态和工作时间 117

Figure 3.12. Labour force contractual status and working hours 118 图 3.12.劳动合同工状况和工作时间 118

Figure 3.13. Strength of association between participation in professional development and contractual status 119 图 3.13.参与专业发展与合同状态之间的关联强度 119

Figure 3.14. Staff sources of work-related stress 120 图 3.14.员工与工作相关的压力来源 120

Figure 3.15. Staff feelings of being valued by children, families and society 121 图 3.15.员工被儿童、家庭和社会重视的感受 121

Figure 3.16. Most likely reasons to leave the ECEC staff role 121 图 3.16.离开 ECEC 工作人员职位的最可能原因 121

Figure 3.17. Pre-primary staff statutory salaries at different points in staff careers (2018) 122 图 3.17.学前班员工在员工职业生涯不同阶段的法定薪金(2018 年) 122

Figure 3.18. Strength of association between use of adaptive practices and working hours 124 图 3.18.使用适应性做法与工作时间之间的关联强度 124

Figure 3.19. Leaders’ characteristics 126 图 3.19.领导者特征 126

Figure 3.20. Elements included in leaders’ formal education 127 图 3.20.领导者正规教育的要素 127

Figure 3.21. Sources of work-related stress for early childhood education and care leaders 128 图 3.21.幼儿教育和护理领导者的工作相关压力来源 128

Figure 3.22. Leaders’ job satisfaction 128 图 3.22.领导者的工作满意度 128

Figure 4.1. Framework for the analysis of centre characteristics associated with practices and process quality in TALIS Starting Strong 137 图 4.1.TALIS 中与实践和流程质量相关的中心特征分析框架 Starting Strong 137

Figure 4.2. Early childhood education and care centre in rural and urban areas 141 图 4.2.农村和城市地区的幼儿教育和护理中心 141

Figure 4.3. The neighbourhood of early childhood education and care centres 142 图 4.3.幼儿教育和护理中心附近 142

Figure 4.4. Locations and buildings of early childhood education and care centres 143 图 4.4.幼儿教育和看护中心的位置和建筑 143

Figure 4.5. Size of early childhood education and care centres 146 图 4.5.幼儿教育及护理中心的规模 146

Figure 4.6. Pre-primary education centres serving younger children 147 图 4.6.为幼儿服务的学前教育中心 147

Figure 4.7. Concentration in centres of children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes 149 图 4.7.来自社会经济弱势家庭的儿童集中在中心 149

Figure 4.8. Percentage of 15-year-old students who had attended preschool for two years or more, by socioeconomic status 152 图 4.8.按社会经济地位分列,上过两年或两年学前班的 15 岁学生的百分比 152

Figure 4.9. Concentration in centres of children with different characteristics 153 图 4.9.集中于具有不同特征的儿童中心 153

Figure 4.10. Human resources in centres 154 图 4.10.中心人力资源 154

Figure 4.11. Average number of staff and children in centres 156 图 4.11.中心工作人员和儿童的平均人数 156

Figure 4.12. Number of staff per ten children in centres, by centre characteristics 158 图 4.12.中心每 10 名儿童的工作人员人数,按中心特征分列 158

Figure 4.13. Number of staff per ten children in centres, according to centre size 159 图 4.13.中心每 10 名儿童的工作人员人数,根据中心规模 159

Figure 4.14. Staff’s educational attainment, by centre characteristics 160 图 4.14.按中心特色分列的工作人员受教育程度 160

Figure 4.15. Share of staff leaving their early childhood education and care centres 161 图 4.15.离开幼儿教育和看护中心的工作人员比例 161

Figure 4.16. Communication with staff/leaders from other centres, by centre characteristics 165 图 4.16.与其他中心的工作人员/领导的沟通,按中心特点 165

Figure 4.17. Communication between pre-primary centres and primary school teachers 167 图 4.17.学前教育中心与小学教师之间的沟通 167

Figure 4.18. Transition practices by centre characteristics: Hold meetings with primary school staff 168 图 4.18.按中心特点划分的过渡做法: 与小学教职员工举行会议 168

Figure 4.19. Transition practices by centre characteristics: Provide activities for parents or guardians to understand transition issues, by centre characteristics 169 图 4.19.按中心特点划分的过渡做法: 按中心特征为家长或监护人提供了解过渡问题的活动 169

Figure 4.20. Staff use of diversity practices, by characteristics of children in the centre 173 图 4.20.按中心儿童的特点分列,工作人员采用多元化做法 173

Figure 5.1. TALIS Starting Strong framework for the analysis of aspects of governance and funding affecting children’s development 183 图 5.1.TALIS 起步 分析影响儿童发展的治理和资金方面的强大框架 183

Figure 5.2. Sources of funding for ECEC centres 186 图 5.2.幼儿保育和教育中心的资金来源 186

Figure 5.3. Distribution of public and private expenditure on ECEC settings in pre-primary education (2016) 187 图 5.3.学前教育中幼儿保育和教育机构的公共和私人支出分配情况(2016 年) 187

Figure 5.4. Exclusively government-funded centres in the public and private sectors 189 图 5.4.公共和私营部门的政府专门资助中心 189

Figure 5.5. Expenditure on early childhood educational development (ISCED 01) and pre-primary education (ISCED 02) 189 图 5.5.幼儿教育发展 (ISCED 01) 和学前教育 (ISCED 02) 的支出 189

Figure 5.6. Change in expenditure on pre-primary education (ISCED 02) as a percentage of GDP 190 图 5.6.学前教育支出(国际教育标准分类法 02)占国内生产总值的百分比变化 190

Figure 5.7. Annual expenditure on early childhood educational institutions per child (2016) 191 图 5.7.每名儿童每年在幼儿教育机构方面的支出(2016 年) 191

Figure 5.8. Responsibilities of centre leaders, governing boards and administrative authorities 198 图 5.8.中心领导、理事会和行政当局的职责 198

Figure 5.9. Share of publicly and privately managed centres in ECEC 202 图 5.9.ECEC 中公共和私人管理中心的份额 202

Figure 5.10. Responsibilities of leaders and/or other staff in publicly and privately managed pre-primary centres 206 图 5.10.公立和私立学前教育中心的领导和/或其他工作人员的责任 206

Figure 5.11. Staff educational attainment in publicly and privately managed ECEC centres 207 图 5.11.公立和私立幼儿保育和教育中心的工作人员受教育程度 207

Figure 5.12. Number of staff per ten children in publicly and privately managed ECEC centres 208 图 5.12.公立和私立幼儿保育中心每10名儿童的工作人员人数 208

Figure 5.13. Lack of support for professional development in publicly and privately managed ECEC centres 209 图 5.13.公共和私营管理的幼儿保育和教育中心缺乏对专业发展的支持 209

Figure 5.14. Geographical location of public and private centres 210 图 5.14.公共和私人中心的地理位置 210

Figure 5.15. Percentage of ECEC centres serving 11% or more of children with a different first language, by centre management 212 图 5.15.按中心管理层分列的幼儿保育和教育中心为 11% 或以上具有不同第一语言的儿童提供服务的百分比 212

Figure 5.16. Percentage of ECEC centres serving 11% or more children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes, by centre management 213 图 5.16.按中心管理层分列的为 11% 或以上来自社会经济弱势家庭的儿童提供服务的幼儿保育和教育中心的百分比 213

Figure A A.1. Organisation of the early childhood education and care system in Chile 220 图 A A.1.智利幼儿教育和照料系统的组织 220

Figure A A.2. Organisation of the early childhood education and care system in Denmark 223 图 A A.2.丹麦幼儿教育和照料系统的组织 223

Figure A A.3. Organisation of the early childhood education and care system in Germany 227 图 A A.3.德国幼儿教育和保育系统的组织 227

Figure A A.4. Organisation of the early childhood education and care system in Iceland 231 图 A A.4.冰岛幼儿教育和护理系统的组织 231

Figure A A.5. Organisation of the early childhood education and care system in Israel 234 图 A A.5.以色列幼儿教育和照料系统的组织 234

Figure A A.6. Organisation of the early childhood education and care system in Japan 238 图 A A.6.日本幼儿教育和护理系统的组织 238

Figure A A.7. Organisation of the early childhood education and care system in Korea 240 图 A A.7.韩国幼儿教育和护理系统的组织 240

Figure A A.8. Organisation of the early childhood education and care system in Norway 243 图 A A.8.挪威幼儿教育和保育系统的组织 243

Figure A A.9. Organisation of the early childhood education and care system in Turkey 247 图 A A.9.土耳其幼儿教育和照料系统的组织 247

Look for the StatLinks any at the bottom of the tables or graphs in this book. To download the matching Excel® spreadsheet, just type the link into your Internet browser, starting with the http://dx.doi.org prefix, or click on the link from the e-book edition. 在本书的表格或图表底部查找 StatLinks any。要下载匹配的 Excel® 电子表格,只需在 Internet 浏览器中键入链接,以 http://dx.doi.org 开头,或单击电子书版本中的链接。

Reader's guide 读者指南

The OECD Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS Starting Strong) is the first international survey that focuses on the workforce in early childhood education and care (ECEC). The results referred to in this volume can be found in Annex DD and through OECD StatLinks at the bottom of the tables and figures throughout the report. 经合组织 (OECD) 的 Starting Strong Teaching and Learning 国际调查 (TALIS Starting Strong) 是首个关注幼儿教育和护理 (ECEC) 劳动力的国际调查。本卷中提到的结果可以在附件 DD 中找到,也可以通过整个报告表格和数字底部的 OECD StatLinks 找到。

Country coverage 国家/地区覆盖

This publication features results from staff and leaders who provide early childhood education and care (ECEC) in pre-primary settings (ISCED level 02) in nine countries (Chile, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Israel, Japan, Korea, Norway, and Turkey), as well as from staff and leaders who provide ECEC to children under age 3 in four countries (Denmark, Germany, Israel and Norway). 本出版物收录了 9 个国家(智利、丹麦、德国、冰岛、以色列、日本、韩国、挪威和土耳其)学前教育和照育 (ECEC) 的工作人员和领导的结果,以及 4 个国家(丹麦、德国、以色列和挪威)为 3 岁以下儿童提供 ECEC 的工作人员和领导的结果。

In the tables throughout the report, countries are ranked in alphabetical order, with one exception: countries that did not meet the standards on TALIS Starting Strong participation rates are placed at the bottom of the tables. Similarly, countries that did not meet the standards on TALIS Starting Strong participation rates are not shown in any figures presenting results of the Survey. 在整份报告的表格中,各国按字母顺序排列,但有一个例外:未达到 TALIS Start-Strong 参与率标准的国家位于表格底部。同样,未达到 TALIS Start-Strong 参与率标准的国家,也不会显示在显示调查结果的任何数字中。

One note applies to the information on data for Israel: 有一点适用于以色列的数据信息:

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. 以色列的统计数据由以色列相关当局提供并由其负责。经合组织使用此类数据并不影响戈兰高地、东耶路撒冷和以色列在约旦河西岸定居点根据国际法条款的地位。

Classification of levels of ECEC and the TALIS Starting Strong sample ECEC 和 TALIS Starting Strong 样本水平的分类

The classification of ECEC settings as pre-primary or serving children under age 3, as well as the other levels of education described in the volume, is based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). ISCED is an instrument for compiling statistics on education internationally. ISCED2011 is the basis of the levels presented in this publication. It distinguishes the following levels of education: 将 ECEC 环境分类为学前儿童或 3 岁以下在职儿童,以及本卷中描述的其他教育水平,均基于国际教育标准分类 (ISCED)。《国际教育标准分类法》是编制国际教育统计数据的工具。ISCED2011 是本出版物中介绍的级别的基础。它区分了以下教育级别:

early childhood education (ISCED level 0) 幼儿教育 (《国际教育标准分类法》0 级)

early childhood educational development (ISCED level 01) 早期儿童教育发展 (《国际教育标准分类法》01 级)

bachelor’s or equivalent (ISCED level 6) 学士或等同 (《国际教育标准分类法》6 级)

master’s or equivalent (ISCED level 7) 硕士或等同 (《国际教育标准分类法》7 级)

doctoral or equivalent (ISCED level 8). 博士或等同物(《国际教育标准分类法》8 级)。

Within early childhood education (ISCED level 0), settings classified under ISCED-2011 have an intentional educational component and aim to develop cognitive, physical and socio-emotional skills necessary for participation in school and society. Programmes at this level are often differentiated by age, with early childhood educational development serving children under age 3 and pre-primary education serving children from age 3 until entry to primary school. Pre-primary settings in TALIS Starting Strong meet the ISCED-2011 definition for ISCED level 02. Settings serving children under age 3 in TALIS Starting Strong were not required to meet the ISCED-2011 definition for ISCED level 01. 在幼儿教育(《国际教育标准分类法》0 级)中,归类为 ISCED-2011 的设置具有有意识的教育成分,旨在发展参与学校和社会所必需的认知、身体和社会情感技能。这一级别的计划通常按年龄进行区分,幼儿教育发展服务于 3 岁以下儿童,学前教育服务于 3 岁以下儿童直至进入小学。TALIS Starting Strong 中的学前教育设置符合 ISCED-2011 对 ISCED 02 级的定义。在 TALIS Starting Strong 中为 3 岁以下儿童服务的设置不需要满足 ISCED-2011 对 ISCED 01 级的定义。

Despite the distinction made by ISCED-2011 within ISCED level 0, many countries, including several participating in TALIS Starting Strong, offer an integrated ECEC system (see Annex A). In integrated ECEC systems, a single government ministry or authority oversees ECEC programmes from birth or age 1 until entry into primary school. For countries with integrated ECEC systems that participated in data collection for both pre-primary settings and settings for children under age 3 (i.e. Denmark, Germany and Norway), the TALIS Starting Strong sampling strategy randomly split ECEC programmes that were expected to cover both age groups to be included in the sampling universe for one population of interest or the other. In this way, programmes could be sampled as part of the pre-primary sample or as part of the sample of settings for children under age 3, but the same programme would not be sampled for both levels of ECEC. 尽管 ISCED-2011 在 ISCED 0 级中进行了区分,但许多国家,包括几个参与 TALIS Start Strong 的国家,都提供综合的 ECEC 系统(见附件 A)。在幼儿保育和教育综合系统中,一个政府部委或当局负责监督从出生或 1 岁到进入小学的幼儿保育和教育计划。对于参与学前教育和 3 岁以下儿童教育 环境数据收集的具有综合 ECEC 系统的国家(即丹麦、德国和挪威),TALIS Starting Strong 抽样策略随机分配了预期涵盖两个年龄组的 ECEC 计划,以纳入一个感兴趣人群或另一个感兴趣人群的抽样范围。这样,课程可以作为学前样本的一部分或作为 3 岁以下儿童环境样本的一部分进行抽样,但不会对两个级别的 ECEC 进行相同的抽样。

Next, staff were sampled within these settings if they were serving children within the designated level of ECEC (see Annex B). As a result, the sample of pre-primary staff and leaders is representative of staff and leaders in settings providing pre-primary education across all nine participating countries, regardless of whether an integrated system exists or not. Similarly, the sample of staff and leaders in settings for children under age 3 is representative of staff and leaders in settings providing services for this age group across all four participating countries, regardless of whether an integrated system exists or not. Home-based settings were included in the samples of settings for children under age 3 in Denmark, Germany and Israel. However, to enhance comparability with pre-primary education settings, data from staff in home-based settings are excluded from this report. These exclusions represent 16% of the settings serving children under age 3 in Denmark, 16% in Germany and 60% in Israel. 接下来,如果工作人员在 ECEC 的指定级别内为儿童服务,则在这些环境中进行抽样(见附件 B)。因此,学前教育工作人员和领导的样本代表了所有 9 个参与国提供学前教育的 教育机构的工作人员和领导,无论是否存在综合系统。同样,3 岁以下儿童机构的工作人员和领导样本代表了所有四个参与国中为该年龄组提供服务的机构的工作人员和领导,无论是否存在综合系统。丹麦、德国和以色列的 3 岁以下儿童环境样本中包括了家庭环境。然而,为了提高与学前教育环境的可比性,本报告不包括来自家庭环境中工作人员的数据。这些排除在丹麦为 3 岁以下儿童提供服务的环境中占 16%,德国为 16%,以色列为 60%。

Readers should bear in mind that the age distinctions in levels of ECEC do not necessarily reflect the organisation of the ECEC system or ECEC programmes in all participating countries (see Annex A). Furthermore, programmes included in the samples for both levels of ECEC may also serve younger or older children. 读者应记住,幼儿保育和教育水平的年龄差异并不一定反映所有参与国的幼儿保育和教育系统或幼儿保育和教育项目的组织情况(见附件 A)。此外,样本中包括的两个 ECEC 级别的计划也可能适用于年龄较小或年龄较大的儿童。

The report uses the term “centres” as shorthand to describe all ECEC settings. The specific programmes or settings vary across and within countries (see Box 1 for details on the types of settings covered in each participating country). 该报告使用术语“中心”作为描述所有 ECEC 设置的简写。具体计划或设置因国家/地区而异(有关每个参与国家/地区涵盖的设置类型的详细信息,请参见方框 1)。

Box 1. ECEC settings included in TALIS Starting Strong 方框 1.TALIS Strong 中包含的 ECEC 设置

Chile 智利

kindergartens, preschools and schools that offer preschool education 幼儿园、学前班和提供学前教育的学校

Denmark 丹麦

kindergartens, integrated institutions, nurseries and day-care facilities 幼儿园、综合机构、托儿所和日托机构

Germany 德国

kindergartens, school kindergartens, pre-school classes, mixed-age ECEC centres and day nurseries 幼稚园、学校幼稚园、学前班、男女混合幼教中心及日间托儿所

Iceland 冰岛

preschools 学前班

Israel 以色列

kindergartens and day-care centres 幼稚园及日托中心

Japan 日本

kindergartens, nursery centres and integrated centres for ECEC 幼稚园、托儿所及幼儿园综合中心

Korea 韩国

kindergartens and childcare centres 幼稚园及幼儿中心

Norway 挪威

kindergartens 幼儿园

Turkey 土耳其

preschools, kindergarten classrooms and practice classrooms 学前班、幼儿园教室和练习教室

Chile kindergartens, preschools and schools that offer preschool education

Denmark kindergartens, integrated institutions, nurseries and day-care facilities

Germany kindergartens, school kindergartens, pre-school classes, mixed-age ECEC centres and day nurseries

Iceland preschools

Israel kindergartens and day-care centres

Japan kindergartens, nursery centres and integrated centres for ECEC

Korea kindergartens and childcare centres

Norway kindergartens

Turkey preschools, kindergarten classrooms and practice classrooms| Chile | kindergartens, preschools and schools that offer preschool education |

| :--- | :--- |

| Denmark | kindergartens, integrated institutions, nurseries and day-care facilities |

| Germany | kindergartens, school kindergartens, pre-school classes, mixed-age ECEC centres and day nurseries |

| Iceland | preschools |

| Israel | kindergartens and day-care centres |

| Japan | kindergartens, nursery centres and integrated centres for ECEC |

| Korea | kindergartens and childcare centres |

| Norway | kindergartens |

| Turkey | preschools, kindergarten classrooms and practice classrooms |

Notes: The settings listed here are the English translations of the setting types within each country. These translations were used for the purposes of creating the TALIS Starting Strong sampling frame. Home-based settings are also included in the TALIS Starting Strong data collection for children under age 3 in Denmark, Germany and Israel, but they are not included in this report. 注意:此处列出的设置是每个国家/地区内设置类型的英文翻译。这些翻译用于创建 TALIS Starting Strong 抽样框架。丹麦、德国和以色列的 TALIS Starting Strong 3 岁以下儿童数据收集中也包括了家庭环境,但未包含在本报告中。

Data underlying the report 报告所依据的数据

TALIS Starting Strong results are based exclusively on self-reports from ECEC staff and leaders and, therefore, represent their opinions, perceptions, beliefs and accounts of their activities. No data imputation from administrative data or other studies is conducted. As with any self-reported data, the information is subjective and may, therefore, differ from data collection through other means (e.g. administrative data or observations). The same is true of leaders’ reports about centre characteristics, sources of funding and practices, which may differ from descriptions provided by administrative data at national or local government levels. TALIS Starting Strong does not directly measure children’s learning, development and well-being and does not provide data on children and families participating in ECEC. TALIS Starting Strong 的结果完全基于 ECEC 员工和领导的自我报告,因此代表了他们对活动的看法、看法、信念和描述。不进行来自行政数据或其他研究的数据插补。与任何自我报告的数据一样,该信息是主观的,因此可能与通过其他方式(例如管理数据或观察)收集的数据不同。领导者关于中心特征、资金来源和做法的报告也是如此,这些报告可能与国家或地方政府层面的行政数据提供的描述不同。TALIS Starting Strong 不直接衡量儿童的学习、发展和福祉,也不提供参与 ECEC 的儿童和家庭的数据。

Results are presented only when estimates are based on at least 10 centres/leaders and/or 30 staff. 只有当估计基于至少 10 个中心/领导和/或 30 名工作人员时,才会提供结果。

Reporting staff and leader data 报告员工和领导数据

As part of the TALIS Starting Strong 2018 data collection, all staff who worked regularly in a pedagogical way with children in officially registered settings providing ECEC in participating countries were eligible to participate ^(1){ }^{1}. Within ECEC settings, centre co-ordinators identified staff as eligible to participate as a centre leader (the person with the most responsibility for administrative, managerial and/or pedagogical leadership) or in one of several roles working directly with children: teacher; assistant; staff for individual children; staff for special tasks; or intern. In some countries, other specific staff roles were also included, but these roles were simultaneously coded to reflect one of the overarching international categories. 作为 2018 年 TALIS Starting Strong 数据收集的一部分,所有在参与国提供 ECEC 的官方注册环境中定期以教学方式与儿童一起工作的工作人员都有资格参加 ^(1){ }^{1} 。在 ECEC 环境中,中心协调员确定工作人员有资格作为中心领导(最负责行政、管理和/或教学领导的人)或担任直接与儿童合作的几个角色之一参与:教师;助理;个别儿童的工作人员;特殊任务的工作人员;或实习生。在一些国家,还包括其他特定的工作人员角色,但这些角色同时被编码以反映一个总体国际类别。

The initial assignment of staff to these categories ensured that all staff who were eligible to participate were included in the sample selection process and, if selected, were asked to complete the relevant questionnaire (leader or staff). A combined questionnaire was used for staff in very small centres (i.e. with only one staff member or with only one main teacher and assisting staff). It included suitable questions both from the staff questionnaire and the leader questionnaire. Respondents who completed these combined questionnaires are included in the data reported for both staff and leaders. 最初将工作人员分配到这些类别可确保所有有资格参与的工作人员都被纳入样本选择过程,如果被选中,则被要求完成相关问卷(领导或工作人员)。对非常小的中心的工作人员(即只有一名工作人员或只有一名主要教师和协助人员)的工作人员使用综合问卷。它包括来自员工问卷和领导者问卷的合适问题。完成这些合并问卷的受访者将包含在为员工和领导者报告的数据中。

The staff categories used to identify staff eligible for participation were also used after data collection to group respondents according to their overall roles in the ECEC centres, focusing on teachers and assistants. Teachers are those with the most responsibility for a group of children. Assistants support the teacher in a group of children. This distinction is used in many of the tables and analyses that provide a comparison between teachers and assistants (for example, Table D.3.1). 在数据收集后,还使用用于确定符合参与条件的员工类别,根据受访者在 ECEC 中心的整体角色对受访者进行分组,重点是教师和助理。教师是对一群孩子负有最大责任的人。助理在一群孩子中为老师提供支持。这种区别在许多提供教师和助理之间比较的表格和分析中使用(例如,表 D.3.1)。

However, several countries do not make a distinction between teachers and assistants in this way. In Japan and Turkey, only teachers work in a pedagogical way with children in ECEC. In Iceland, a shortage of certified ECEC teachers means that staff without this credential (i.e. assistants) may be serving as teachers in some settings. So this overall role distinction in TALIS Starting Strong is not meaningful for Iceland. In centres serving children under age 3 in Israel, fewer than 1%1 \% of participating staff were identified as assistants, making the comparison between teachers and assistants impossible for this population as well. In the remaining countries and populations (Chile, Denmark, Germany, Israel in pre-primary education settings, Korea and Norway), the roles of teacher and assistant can, but do not necessarily, reflect differences in staff credentials. Rather, for TALIS Starting Strong the difference between teachers and assistants is defined to reflect the roles that staff members typically have within their centres. 但是,一些国家并没有以这种方式区分教师和助理。在日本和土耳其,只有教师以教学方式与 ECEC 儿童一起工作。在冰岛,经过认证的 ECEC 教师短缺意味着没有此证书的工作人员(即助理)可能在某些情况下担任教师。因此,TALIS Start Strong 中的这种整体角色区分对冰岛来说没有意义。在以色列为 3 岁以下儿童提供服务的中心中,被确定为助理的工作人员少于 1%1 \% 参与的工作人员,这使得教师和助理之间的比较也无法对这一人群进行比较。在其余国家和人口(智利、丹麦、德国、学前教育环境中的以色列、韩国和挪威),教师和助理的角色可以但不一定反映出工作人员资历的差异。相反,对于 TALIS Starting Strong 来说,教师和助理之间的区别被定义为反映工作人员在其中心内通常扮演的角色。

Reporting staff data 报告员工数据

The report uses the term “staff” as shorthand for the TALIS Starting Strong population of teachers, assistants, staff for individual children, staff for special tasks and interns. In addition, leaders who also had staff duties (e.g. those working alone or in very small centres) are included in the staff data throughout this report. 该报告使用“工作人员”一词作为 TALIS Starting Strong 人口的简写,包括教师、助理、个别儿童工作人员、特殊任务工作人员和实习生。此外,在本报告的员工数据中还包括了同样负有员工职责的领导者(例如,那些单独工作或在非常小的中心工作的领导者)。

Reporting leader data 报告领先数据

The report uses the term “leader” to identify the person who was identified as having the most responsibility for administrative, managerial and/or pedagogical leadership in their centres. Responses from leaders who also had staff duties (e.g. those working alone or in very small centres) are included in both the leader data and the staff data throughout this report. Leaders provided information on the characteristics of their centres and their own work and working conditions by completing a leader questionnaire or a combined questionnaire. Where responses from leaders are presented in this publication, they are usually weighted to be representative of leaders. In some cases, leader responses are treated as attributes of staff working conditions. In such cases, leaders’ answers are analysed at the staff level and weighted to be representative of staff (see Annex C). 该报告使用“领导者”一词来确定被确定为在其中心的行政、管理和/或教学领导方面负有最大责任的人。在整个报告中,领导者数据和员工数据中都包含了同样承担员工职责的领导者(例如,那些单独工作或在非常小的中心工作的领导者)的回答。领导者通过完成领导者问卷或综合问卷,提供有关其中心的特点以及他们自己的工作和工作条件的信息。在本出版物中介绍领导者的回应时,它们通常会被加权以代表领导者。在某些情况下,领导的回答被视为员工工作条件的属性。在这种情况下,领导的回答将在工作人员层面进行分析,并进行加权以代表工作人员(见附件 C)。

Staff reports of their own roles in the target group 员工报告自己在目标群体中的角色

In addition to the initial categories used to classify staff for participation in TALIS Starting Strong, staff who participated in the Survey had the opportunity to describe their roles within a specific group. Staff were asked to consider the first group of children that they worked with on their last working day before the Survey (the target group) and to select the category that best represented their role in that group on that day (leader, teacher, assistant, staff for individual children, staff for special tasks, intern or other). Throughout the report, those who describe themselves as “leaders” and “teachers” are grouped together to describe the staff with the most responsibility in the target group. 除了用于对参与 TALIS Start Strong 的员工进行分类的初始类别外,参与调查的员工还有机会描述他们在特定群体中的角色。工作人员被要求考虑在调查前最后一个工作日与他们一起工作的第一组儿童(目标组),并选择最能代表他们在当天在该组中的角色的类别(领导、教师、助理、个别儿童的工作人员、特殊任务的工作人员、实习生或其他)。在整个报告中,那些自称“领导者”和“老师”的人被归为一组,以描述目标群体中责任最大的员工。

These staff reports do not necessarily reflect staff members’ broader roles in the ECEC centre, but they provide contextual information for other questions that were asked about the target group. These role distinctions are used in tables and analyses that focus on the target group (see, for example, Chapter 2, Figure 2.14). 这些工作人员报告不一定反映工作人员在 ECEC 中心更广泛的作用,但它们为被问及的有关目标群体的其他问题提供了背景信息。这些角色差异用于关注目标群体的表格和分析中(例如,参见第 2 章,图 2.14)。

Leader reports of roles within their centres 领导报告其中心内的角色

Leaders provided an overview of the number of staff in each category working in their ECEC centres (leaders, teachers, assistants, staff for individual children, staff for special tasks, interns and other staff). These data cannot be linked to individual staff responses on the questionnaire, but they give a summary of the human resources available in each participating ECEC centre. These role distinctions are used in tables and analyses at the centre level (see, for example, Chapter 4, Figure 4.10). 领导们概述了在其 ECEC 中心工作的每个类别的工作人员数量(领导、教师、助理、个别儿童的工作人员、特殊任务的工作人员、实习生和其他工作人员)。这些数据无法与调查问卷中的个别工作人员回答相关联,但它们提供了每个参与的 ECEC 中心可用的人力资源摘要。这些角色区分用于中心级别的表格和分析中(例如,参见第 4 章,图 4.10)。

Reporting data on the number of children 报告儿童数量数据

For a subset of questions, staff reported on their work with the target group (the first group of children that they worked with on their last working day before the Survey). In some cases, the target group may reflect a stable group of children and adults. In other cases, the target group may reflect a staff member’s full day of work, involving many other staff (e.g. those who join the group for special activities or who come to ensure that the required group ratios are maintained while another staff member takes a break) and perhaps a changing set of children as well. 对于一部分问题,工作人员报告了他们与目标群体(他们在调查前最后一个工作日工作的第一组儿童)的工作。在某些情况下,目标群体可能反映了一个稳定的儿童和成人群体。在其他情况下,目标群体可能反映一名工作人员的全天工作,涉及许多其他工作人员(例如,那些参加特殊活动的人,或来确保在另一名工作人员休息时保持所需的小组比例的人),也可能包括一组不断变化的儿童。

To better understand the numbers of staff and children that interact together in these target groups, this report refers to the number of staff per child in the target group. In regard to target groups, the “number of staff per child” refers to the total number of staff working in the target group, regardless of their role, divided by the number of children in the target group. Because the number of staff per individual child is low, when specific examples are cited for comparative purposes, they are presented as the “number of staff per ten children” in the target group. This grouping of ten children is designed to facilitate comparisons across different staffing approaches and different countries. It does not imply that target groups include only or exactly ten children; some target groups may be larger and others smaller. The results can be interpreted as the average number of staff (i.e. leaders, teachers, assistants, staff for individual children, staff for special tasks, interns or others) with whom a group of ten children may interact at various points during their time in the target group. See Box 2.3 in Chapter 2 and Annex C for further details on the computation of this indicator. 为了更好地了解在这些目标群体中一起互动的员工和儿童的数量,本报告引用了目标群体中每个儿童的员工数量。就目标群体而言,“每名儿童的工作人员人数”是指在目标群体中工作的工作人员总数(无论其角色如何)除以目标群体中的儿童人数。由于每个儿童的教职员工人数较少,因此当出于比较目的引用具体示例时,它们在目标群体中被表示为“每 10 名儿童的教职员工人数”。这组 10 名儿童旨在促进不同人员配置方法和不同国家/地区的比较。这并不意味着目标群体仅包括或恰好包括 10 个孩子;一些目标群体可能更大,而另一些目标群体可能更小。结果可以解释为一组 10 名儿童在目标群体中的不同时间点可能与之互动的工作人员(即领导、教师、助理、个别儿童的工作人员、特殊任务的工作人员、实习生或其他人员)的平均数量。有关该指标计算的更多详细信息,请参见第 2 章的方框 2.3 和附件 C。

In addition to reporting the number of staff working in their centres, leaders also report on the number of children enrolled in their centres. To understand the numbers of staff and children that interact together in centres, this report also refers to the number of staff per child in the centre. In regard to centres, the “number of staff per child” refers to the total number of staff working in a centre, regardless of their role, divided by the total number of children enrolled. Again, because the number of staff per individual child is low, when specific examples are cited for comparative purposes, they are presented as the “number of staff per ten children” in the centre. The results can be interpreted as the average number of staff (i.e. leaders, teachers, assistants, staff for individual children, staff for special tasks, interns or others) with whom a group of ten children may interact at various points during their time in the centre. See Box 4.4 in Chapter 4 and Annex C for further details on the computation of this indicator. 除了报告在其中心工作的工作人员人数外,领导者还报告在其中心注册的儿童人数。为了了解在中心内互动的工作人员和儿童的数量,本报告还提到了中心内每个儿童的工作人员人数。就中心而言,“每名儿童的工作人员人数”是指在中心工作的工作人员总数(无论其角色如何)除以注册儿童总数。同样,由于每个儿童的工作人员人数较少,当出于比较目的引用具体例子时,它们在中心被表示为“每 10 名儿童的工作人员人数”。结果可以解释为一组 10 名儿童在中心期间在不同时间点可能与之互动的平均工作人员(即领导、教师、助理、个别儿童的工作人员、特殊任务的工作人员、实习生或其他人员)。有关该指标计算的更多详细信息,请参见第 4 章的方框 4.4 和附件 C。

These TALIS Starting Strong indicators on the “number of staff per child” differ from regulated child-to-staff ratios, as they do not take into account factors such as whether staff members are working full-time or part-time, the number of hours during which each child attends the centre, and the time staff are expected to directly interact with children (versus time when staff may be present at the centre but engaged in other types of work, such as planning or professional development). 这些关于“每名儿童的工作人员人数”的 TALIS Starting Strong 指标与规定的儿童与工作人员比率不同,因为它们没有考虑诸如工作人员是全职还是兼职工作、每个儿童在中心就读的小时数以及工作人员与儿童直接互动的时间等因素(与工作人员可能在中心但从事其他类型工作的时间相比, 例如规划或专业发展)。

International averages 国际平均值

Cross-country averages are provided for pre-primary settings throughout the report. These averages correspond to the arithmetic mean of the nine country estimates. 整个报告都提供了学前教育环境的跨国平均值。这些平均值对应于 9 个国家/地区估计值的算术平均值。

Symbols used in tables 表格中使用的符号

Five symbols are used to denote non-reported estimates: 五个符号用于表示未报告的估计值:

a: The question was not administered in the country because it was optional. 答:该问题未在该国进行管理,因为它是可选的。

c: There are too few or no observations to provide reliable estimates and/or to ensure the confidentiality of respondents (i.e. there are fewer than 10 centres/leaders and/or 30 staff with valid data and/or the item non-response rate [i.e. ratio of missing or invalid responses to the number of participants for whom the question was applicable] is above 50%50 \% ). c:观察结果太少或没有,无法提供可靠的估计和/或确保受访者的机密性(即拥有有效数据和/或项目未回复率的少于 10 个中心/领导和/或 30 名工作人员 [即缺失或无效回复与问题适用的参与者人数的比率] 高于 50%50 \% )。

m: Data were collected but subsequently removed for technical reasons (e.g. low participation rate) as part of the data adjudication process. m:作为数据评审过程的一部分,收集了数据,但随后由于技术原因(例如参与率低)而被删除。

p: Data were collected but not reported for technical reasons (e.g. low participation rate) as part of the data adjudication process. p:作为数据评审过程的一部分,由于技术原因(例如参与率低),收集了数据但未报告。

w : Data were withdrawn or were not collected at the request of the country concerned. w : 数据被撤回或未应相关国家/地区的要求收集。

Rounding figures 四舍五入数字

Because of rounding, some figures in tables may not add up exactly to the totals. Totals, differences and averages are always calculated on the basis of exact numbers and are rounded only after calculation. 由于四舍五入的原因,表格中的某些数字加起来可能不完全等于总数。总计、差额和平均值始终根据精确数字计算,并且仅在计算后四舍五入。

All standard errors in the publication have been rounded to one, two or three decimal places. Where the value 0.0,0.000.0,0.00 or 0.000 is shown, this does not imply that the standard error is zero, but that it is smaller than 0.05,0.0050.05,0.005 or .0005 , respectively. 出版物中的所有标准错误均已四舍五入到小数点后一位、两位或三位。如果显示值 0.0,0.000.0,0.00 或 0.000,这并不意味着标准误差为零,而是分别小于 0.05,0.0050.05,0.005 或 .0005 。

Statistically significant differences 统计学上显著的差异

Statistically significant differences are denoted using different colours in figures. See Annex C for further information. 在图形中使用不同的颜色表示统计上显著的差异。有关更多信息,请参见附件 C。

Additional data sources 其他数据源

Throughout the report, additional data sources are included to better understand the context of ECEC systems in participating countries. The two primary sources of additional data are OECD’s Education at a Glance publication and an OECD policy survey on Quality beyond Regulations. The Education at a Glance series provides key information on the organisation of education systems, access to different levels of education and financial resources invested in education, as well as information on the staff and teachers working in education settings. The OECD Quality beyond Regulations policy survey provides data on the policies and regulations governing aspects of quality in ECEC settings. It was completed in 2019 by ministries and governing authorities responsible for the oversight of ECEC in countries, including the countries participating in TALIS Starting Strong. This publication presents first findings of the OECD Quality beyond Regulations policy survey for countries participating in TALIS Starting Strong. 在整个报告中,包括其他数据来源,以更好地了解参与国 ECEC 系统的背景。额外数据的两个主要来源是经合组织的《教育概览》出版物和经合组织关于超越法规的质量的政策调查。“教育概览”系列提供了有关教育系统组织、获得不同层次教育的机会和投资于教育的财政资源的关键信息,以及有关在教育环境中工作的工作人员和教师的信息。经合组织 (OECD) 超越法规的质量政策调查提供了有关管理 ECEC 环境中质量方面的政策和法规的数据。该计划于 2019 年由负责监督幼儿保育教育的国家(包括参与 TALIS Start Strong 的国家)的部委和管理机构完成。本出版物介绍了经合组织 (OECD) “超越法规的质量”政策调查的初步结果,调查对象是参与 TALIS 的“强势起步”国家。

Abbreviations 缩写

ECEC early childhood education and care 幼儿教育和保育

ISCED International Standard Classification of Education 《国际教育标准分类法》国际教育标准分类法

PPP purchasing power parity (i.e. the purchasing power of staff salaries using a common currency [USD] to facilitate cross-country comparisons) 购买力平价(即使用共同货币 [USD] 的员工工资购买力,以便于进行跨国比较)

S.D. standard deviation 标准差

S.E. standard error SE 标准误差

Further technical documentation 更多技术文档

For further information on the TALIS Starting Strong instruments and the methods used, see the TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Technical Report (OECD, 2019[1]). 有关 TALIS Starting Strong 工具和所用方法的更多信息,请参阅 TALIS Starting Strong 2018 技术报告(经合组织,2019 年[1])。

This report uses the OECD StatLinks service. All tables and figures are assigned a URL leading to a corresponding Excel ^("TM "){ }^{\text {TM }} workbook containing the underlying data. These URLs are stable and will remain unchanged over time. In addition, readers of the e-books will be able to click directly on these links, and the workbook will open in a separate window if their Internet browser is open and running. 此报告使用 OECD StatLinks 服务。所有表格和插图都分配了一个 URL,该 URL 指向包含基础数据的相应 Excel ^("TM "){ }^{\text {TM }} 工作簿。这些 URL 是稳定的,并且会随着时间的推移保持不变。此外,电子书的读者将能够直接单击这些链接,如果他们的 Internet 浏览器打开并运行,工作簿将在单独的窗口中打开。

^(1){ }^{1} For detailed information on data collection procedures, please refer to the TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Technical Report (OECD, 2019[1]). ^(1){ }^{1} 有关数据收集程序的详细信息,请参阅 TALIS Starting Strong 2018 技术报告(经合组织,2019 年[1])。

Executive summary 摘要

The OECD Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS Starting Strong) asks early childhood education and care (ECEC) staff and leaders in nine participating countries (Chile, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Israel, Japan, Korea, Norway, and Turkey) about their characteristics, the practices they use with children, their beliefs about children’s development and their views on the profession and on the ECEC sector. This first volume of findings from TALIS Starting Strong, Providing Quality Early Childhood Education and Care, examines these multiple factors that are known to determine quality and thereby influence children’s learning, development and well-being. 经合组织 Starting Strong Teaching and Learning 国际调查 (TALIS Starting Strong) 询问了九个参与国家(智利、丹麦、德国、冰岛、以色列、日本、韩国、挪威和土耳其)的幼儿教育和护理 (ECEC) 工作人员和领导者,了解他们的特点、他们对儿童使用的做法、他们对儿童发展的看法以及他们对职业和 ECEC 部门的看法。TALIS 的第一卷调查结果来自 TALIS 起点,提供优质的幼儿教育和护理,研究了这些已知决定质量并因此影响儿童学习、发展和福祉的多个因素。

What the data tell us 数据告诉我们什么

Interactions between children, staff and parents/guardians in early childhood education and care centres 幼儿教育和护理中心的儿童、工作人员和家长/监护人之间的互动

Around 70%70 \% of staff report regular use of practices facilitating children’s socio-emotional development (such as encouraging children to help each other) or practices facilitating children’s language development (such as singing songs or rhymes). Specific practices emphasising literacy and numeracy (such as playing with letters or playing number games) are used to a lesser extent. 周围的 70%70 \% 工作人员报告说,他们经常使用促进儿童社会情感发展的做法(如鼓励儿童互相帮助)或促进儿童语言发展的做法(如唱歌或押韵)。强调识字和算术的特定练习(例如玩字母或玩数字游戏)的使用程度较低。

Related to this, the ability to co-operate easily with others is at the top of the list of skills and abilities that ECEC staff regard as important for young children to develop. 与此相关,与他人轻松合作的能力是 ECEC 工作人员认为对幼儿发展很重要的技能和能力列表的首位。

Exchanging information with parents regarding daily activities and children’s development is common. Smaller percentages of staff report encouraging parents to play and carry out learning activities at home with their children. 与父母交换有关日常活动和儿童发展的信息是很常见的。较小比例的员工报告说鼓励家长在家中与孩子一起玩耍和开展学习活动。

In pre-primary education centres, the average size of the target group (defined as the first group of children staff were working with on the last working day before the day of the Survey) varies from 15 children to more than 20 . Staff working with larger groups report using more behavioural support practices (such as asking children to quieten down). 在学前教育中心,目标群体(定义为工作人员在调查前最后一个工作日与第一批儿童一起工作的儿童)的平均人数从 15 名儿童到 20 多名儿童不等。与大型团体合作的工作人员报告说,他们使用了更多的行为支持做法(例如要求孩子安静下来)。

Teachers, assistants and leaders in early childhood education and care 幼儿教育和保育的教师、助理和领导者

Staff in the ECEC field have typically completed education beyond secondary school, with Japan, Korea and Turkey having the highest rates of ECEC staff with post-secondary education. Training specifically to work with children is not universal, ranging from 64%64 \% of staff in Iceland to 97%97 \% of staff in Germany. Staff with more education and training and more responsibility report that they adapt their practices in the classroom or playroom to individual children’s development and interests. ECEC 领域的工作人员通常完成了中学以上的教育,其中日本、韩国和土耳其的 ECEC 工作人员受过高等教育的比例最高。专门针对儿童工作的培训并不普遍,从 64%64 \% 冰岛的工作人员到 97%97 \% 德国的工作人员。接受更多教育和培训并承担更多责任的员工报告说,他们根据每个孩子的发展和兴趣调整了他们在教室或游戏室的做法。

In all countries, a majority of staff (more than 75%) report having participated in professional development activities within the 12 months prior to the Survey, with particularly strong rates of participation in Korea and Norway. However, staff who are less educated tend to participate less in professional development activities. 在所有国家,大多数员工(超过 75%)报告说在调查前 12 个月内参加过专业发展活动,韩国和挪威的参与率尤其高。然而,受教育程度较低的员工往往较少参与专业发展活动。

Staff in all countries report feeling more valued by the children they serve and their parents or guardians than by society in general. Satisfaction with salaries is low. Even so, staff report high levels of overall job satisfaction. In several countries, staff who feel that ECEC staff are more valued by society report more use of practices in the classroom or playroom adapted to individual children’s development and interests. 所有国家的工作人员都表示,他们感到所服务的儿童及其父母或监护人比整个社会更受重视。对薪水的满意度很低。即便如此,员工报告的整体工作满意度很高。在一些国家,认为幼儿保育和教育 教育工作人员更受社会重视的工作人员报告说,在教室或游戏室中更多地使用适合儿童个人发展和兴趣的做法。

Lack of resources and having too many children in the classroom or playroom are major sources of work-related stress among ECEC staff. For centre leaders, a primary source of work-related stress is having too much administrative work associated with their job. Leaders also report that inadequate resources for the centre and staff shortages are the main barriers to effectiveness. 缺乏资源和教室或游戏室里有太多孩子是 ECEC 工作人员与工作相关的压力的主要来源。对于中心领导来说,与工作相关的压力的主要来源是与他们的工作相关的太多行政工作。领导们还报告说,该中心资源不足和员工短缺是影响成效的主要障碍。

Early childhood education and care centres and structural features of quality environments 幼儿教育和保育中心与优质环境的结构特征

ECEC centres are generally characterised as stand-alone buildings. In several countries, co-location with a primary school is associated with more frequent meetings and communication with primary school staff and transition-related activities for parents and guardians. 幼儿保育和教育中心通常被描述为独立的建筑。在一些国家/地区,与小学共址与更频繁的与小学工作人员的会议和沟通以及家长和监护人的过渡相关活动有关。

There is little indication that ECEC centres with larger shares of children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes benefit from enhanced structural conditions and services (e.g. higher staff qualifications or a more favourable number of staff per child). 几乎没有迹象表明,来自社会经济弱势家庭的儿童比例较高的幼儿保育和教育中心受益于更好的结构条件和服务(例如,更高的工作人员资格或每个儿童的工作人员数量更有利)。

More than a third of centres in Germany, Iceland and Norway have 11%11 \% or more children whose first language differs from the language(s) used in the centre, while this is rare in Japan and Korea. In Chile, Germany and Iceland, staff in pre-primary centres with more children who have a different first language also report greater use of activities related to children’s diversity. 在德国、冰岛和挪威,超过三分之一的幼儿园有 11%11 \% 或更多的儿童的第一语言与幼儿园使用的语言不同,而在日本和韩国这种情况很少见。在智利、德国和冰岛,拥有更多不同母语儿童的学前教育中心的工作人员也报告说,他们更多地使用与儿童多样性相关的活动。

Governance, funding and the quality of early childhood education and care 治理、资金以及幼儿教育和保育的质量

In participating countries, more than 90%90 \% of centres receive government funds. Parents are also involved in the funding of ECEC centres, with more than 60% of centres receiving funds from parents in all countries surveyed except Chile and Iceland. 在参与国,超过 90%90 \% 一个中心获得政府资金。家长也参与了幼儿保育和教育中心的资助,除智利和冰岛外,在接受调查的所有国家,超过 60% 的中心从家长那里获得资金。

Staff across countries and levels of education concur that reducing group size, improving staff salaries and receiving support for children with special needs are important spending priorities. Having opportunities for high-quality professional development also appears as a top priority for staff, particularly in centres for children under age 3. 不同国家和不同教育层次的工作人员都认为,减少小组规模、提高工作人员工资和为有特殊需要的儿童提供支持是重要的支出重点。拥有高质量专业发展的机会似乎也是工作人员的首要任务,尤其是在 3 岁以下儿童中心。

The share of privately managed centres varies from 10%10 \% in Israel to 70%70 \% in Germany. Privately managed centres benefit from more autonomy in the management of budget and human resources. Publicly managed centres are more likely to be located in more rural areas than privately managed centres in almost all countries surveyed. 私人管理的中心的份额从 10%10 \% 以色列到 70%70 \% 德国不等。私人管理中心在预算和人力资源管理方面享有更大的自主权。在几乎所有接受调查的国家中,公共管理的中心比私人管理的中心更有可能位于更多的农村地区。

Monitoring activities tend to focus more frequently on assessing the facilities and financial situation of centres than on the quality of interactions between staff and children (i.e. process quality). More than 20% of leaders in Germany and Japan report that their centres have never been evaluated on process quality. 监测活动往往更频繁地侧重于评估中心的设施和财务状况,而不是工作人员和儿童之间的互动质量(即过程质量)。在德国和日本,超过 20% 的领导者表示,他们的中心从未接受过过程质量评估。

What TALIS Starting Strong implies for policies TALIS Start Strong 对策略意味着什么

The findings presented in this report suggest four major objectives for policies to ensure high quality ECEC: 本报告提出的研究结果提出了确保高质量幼儿保育和教育的政策的四个主要目标:

Promoting practices that foster children’s learning, development and well-being: This points to pre-service and in-service education and training programmes that can support staff in their use of relevant practices, well designed curriculum frameworks, and flexible organisation of activities that ensure interactions of staff with small groups of children. 促进促进儿童学习、发展和福祉的做法:这表明职前和在职教育和培训计划可以支持员工使用相关做法、精心设计的课程框架以及灵活的活动组织,以确保员工与小团体儿童的互动。

Attracting and retaining a high-quality workforce: This points to policies that can raise the status of the profession through adequate salaries, reduced sources of instability and stress, and access to relevant and flexible professional development opportunities. 吸引和留住高素质的劳动力:这表明可以通过适当的工资、减少不稳定和压力的来源以及获得相关和灵活的专业发展机会来提高该行业地位的政策。

Giving a strong start to all children: This points to policies that ensure access to high quality ECEC for children facing greater barriers, prepare staff to adapt their practices to the needs of children with different characteristics, and allocate resources to provide additional support where required. 为所有儿童提供一个良好的开端:这表明政策应确保面临更大障碍的儿童获得高质量的 ECEC,让工作人员做好准备以适应具有不同特征的儿童的需求,并分配资源以在需要时提供额外的支持。

Ensuring smart spending in view of complex governance and service provision: This points to policies to identify and agree on the spending priorities, develop assessment and monitoring frameworks that support quality, and empower ECEC centre leaders. 鉴于复杂的治理和服务提供,确保明智的支出:这表明需要制定政策来确定和商定支出优先事项,制定支持质量的评估和监测框架,并赋予 ECEC 中心领导权力。

Policies to raise the quality of ECEC face a number of trade-offs in terms of the areas to invest in and the areas to spend less on. TALIS Starting Strong sheds light on what could be priorities for each country. This report also suggests flexible and co-ordinated approaches that can be less costly and easier to implement than radical changes. 提高幼儿保育和教育质量的政策在投资领域和减少支出的领域方面面临许多权衡取舍。TALIS Start Strong 阐明了每个国家/地区的优先事项。本报告还提出了灵活和协调的方法,与激进的变革相比,这些方法的成本更低且更容易实施。

What is TALIS Starting Strong? 什么是 TALIS Beginning Strong?

Introduction 介绍

The OECD Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS Starting Strong) is an international, large-scale survey of staff and leaders in early childhood education and care (ECEC). TALIS Starting Strong uses questionnaires administered to staff and leaders to gather data. Its main goal is to generate robust international information relevant to developing and implementing policies focused on ECEC staff and leaders and their pedagogical and professional practices, with an emphasis on those aspects that promote conditions for children’s learning, development and well-being. It gives ECEC staff and leaders an opportunity to share their insights, allowing them to provide input into policy analysis and development in key areas. It is also a collaboration between participating countries, the OECD and an international research consortium. TALIS Starting Strong builds on the OECD’s 20 years of experience in conducting ECEC policy reviews in the context of the Starting Strong series, the guidance of the OECD Network on Early Childhood Education and Care and the established TALIS programme collecting data from school principals and teachers. 经合组织 (OECD) 的 Start Strong 教学国际调查 (TALIS Starting Strong) 是一项针对幼儿教育和护理 (ECEC) 工作人员和领导者的国际性大规模调查。TALIS Starting Strong 使用对员工和领导进行的问卷调查来收集数据。其主要目标是生成与制定和实施以 ECEC 工作人员和领导者及其教学法和专业实践为重点的政策相关的强大国际信息,重点是促进儿童学习、发展和福祉条件的那些方面。它为 ECEC 工作人员和领导者提供了分享见解的机会,使他们能够为关键领域的政策分析和发展提供意见。它也是参与国、经合组织和国际研究联盟之间的合作。“助学教育计划”以经合组织 20 年来在“强势出发”系列、经合组织幼儿教育和保育网络的指导以及已建立的助教教育和教育计划收集校长和教师数据的背景下进行幼儿保育和教育政策审查的经验为基础。

TALIS Starting Strong seeks to serve the goals of its three main beneficiaries: policy makers, ECEC practitioners and researchers. First, it aims to help policy makers review and develop policies that promote high-quality ECEC, for both professionals in the field and children. Second, TALIS Starting Strong aims to help staff, leaders and ECEC stakeholders to reflect upon and discuss their practice and find ways to enhance it. Third, TALIS Starting Strong builds upon past research to inform the future work of researchers. TALIS Start Strong 旨在为其三个主要受益者的目标服务:政策制定者、ECEC 从业者和研究人员。首先,它旨在帮助政策制定者审查和制定政策,促进为该领域的专业人士和儿童提供高质量的 ECEC。其次,TALIS Starting Strong 旨在帮助员工、领导者和 ECEC 利益相关者反思和讨论他们的实践,并找到改进它的方法。第三,TALIS Starting Strong 建立在过去研究的基础上,为研究人员的未来工作提供信息。

Which countries participate in TALIS Starting Strong? 哪些国家/地区参与了 TALIS Start Strong?

TALIS Starting Strong 2018 includes nine countries: Chile, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Israel, Japan, Korea, Norway and Turkey. All of these countries collected data from staff and leaders in pre-primary education (ISCED level 02) settings. In addition, four of the nine countries (Denmark, Germany, Israel and Norway) collected data from staff and leaders in settings serving children under age 3. TALIS 2018 年强势起步计划包括 9 个国家/地区:智利、丹麦、德国、冰岛、以色列、日本、韩国、挪威和土耳其。所有这些国家都从学前教育(《国际教育标准分类法》02 级)环境中的工作人员和领导那里收集了数据。此外,9 个国家中有 4 个国家(丹麦、德国、以色列和挪威)收集了为 3 岁以下儿童提供服务的机构的工作人员和领导的数据。

What is TALIS Starting Strong about? TALIS Start Strong 是什么?

TALIS Starting Strong has a cross-cutting focus on equity and diversity in addition to the 11 main areas covered by the Survey: 除了调查涵盖的 11 个主要领域外,TALIS Start Strong 还关注公平和多元化:

process quality (the quality of interactions between staff and children and staff and parents/guardians, as well as among children) 流程质量(员工与儿童之间、员工与家长/监护人之间以及儿童之间的互动质量)

monitoring of children’s learning, development and well-being 监测儿童的学习、发展和福祉

background and initial preparation of staff and leaders 员工和领导者的背景和初步准备

professional development for staff and leaders 员工和领导者的专业发展

staff and leader well-being 员工和领导者的福祉

professional beliefs about children’s learning, development and well-being 关于儿童学习、发展和福祉的专业信念

staff self-efficacy 员工自我效能感

structural quality (i.e. available physical, human, and material resources), pedagogical and administrative leadership 结构质量(即可用的物质、人力和物质资源)、教学和行政领导

climate 气候

stakeholder relations. 利益相关者关系。

More information on the conceptualisation of these areas is available in the Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey 2018 Conceptual Framework (Sim et al., 2019[2]). 有关这些领域概念化的更多信息,请参见 2018 年 Starting Strong Teaching and Learning 国际调查概念框架(Sim et al., 2019[2])。

What are the key features of the TALIS Starting Strong design? 达丽思 Starting Strong 设计的主要特点是什么?

The key features of the TALIS Starting Strong design are as follows: TALIS Starting Strong 设计的主要特点如下:

Target sample size: Minimum of 180 ECEC settings per country and level of ECEC (pre-primary education and settings serving children under age 3). 目标样本量:每个国家和 ECEC 级别(学前教育和为 3 岁以下儿童服务的环境)至少 180 个 ECEC 环境。