Abstract 抽象

In-field Sound Speed Profile (SSP) measurement is still indispensable for achieving centimeter-level-precision Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS)-Acoustic (GNSS-A) positioning in current state of the art. However, in-field SSP measurement on the one hand causes a huge cost and on the other hand prevents GNSS-A from global seafloor geodesy especially for real-time applications. We propose an Empirical Sound Speed Profile (ESSP) model with three unknown temperature parameters jointly estimated with the seafloor geodetic station coordinates, which is called the 1st-level optimization. Furthermore, regarding the sound speed variations of ESSP we propose a so-called 2nd-level optimization to achieve the centimeter-level-precision positioning for monitoring the seafloor tectonic movement. Long-term seafloor geodetic data analysis shows that, the proposed two-level optimization approach can achieve almost the same positioning result with that based on the in-field SSP. The influence of substituting the in-field SSP with ESSP on the horizontal coordinates is less than 3 mm, while that on the vertical coordinate is only 2–3 cm in the standard deviation sense.

在当前技术水平下,现场声速剖面 (SSP) 测量对于实现厘米级精度的全球导航卫星系统 (GNSS)-声学 (GNSS-A) 定位仍然是必不可少的。然而,现场 SSP 测量一方面会导致巨大的成本,另一方面又使 GNSS-A 无法进行全球海底大地测量,尤其是对于实时应用。我们提出了一个经验声速剖面 (ESSP) 模型,该模型具有三个未知温度参数,与海底大地测量站坐标联合估计,称为一级优化。此外,关于 ESSP 的声速变化,我们提出了一种所谓的二级优化,以实现厘米级精度定位,以监测海底构造运动。长期海底大地测量数据分析表明,所提出的两级优化方法能够获得与基于现场 SSP 的定位结果几乎相同的定位结果。用 ESSP 代替场内 SSP 对水平坐标的影响小于 3 mm,而在标准差意义上,对垂直坐标的影响仅为 2-3 cm。

Similar content being viewed by others

其他人正在查看类似内容

Explore related subjects

探索相关主题

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.发现来自相关学科研究人员的最新文章和新闻,建议使用机器学习。

Introduction 介绍

Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS)-Acoustic (GNSS-A) positioning technique has become a vital tool for seafloor geodesy and crustal deformation applications of submarine offshore regions (Bürgmann & Chadwell, 2014; Iinuma et al., 2021). GNSS-A positioning technique was pioneered by Fred Spiess (Spiess, 1985; Spiess et al., 1998) and further developed for more than two decades (Chadwell & Sweeney, 2010; Chadwell et al., 1997). Regional seafloor geodetic networks were established in the past (Poutanen & Rózsa, 2020; Yang et al., 2020) and had provided key observations for constraining tectonic motion, crustal deformation and the earthquake cycle (Gagnon & Chadwell, 2007; Gagnon et al., 2005; Iinuma et al., 2021; Kido et al., 2006; Sato et al., 2011). GNSS-A technique achievements made in the past are on the one hand from observation scheme advances (Kido et al., 2008; Sato et al., 2013; Spiess et al., 1998) and on the other hand from acoustic positioning model improvements (Asada & Yabuki, 2006; Fujita et al., 2006; Spiess, 1980; Watanabe et al., 2020; Yang & Qin, 2020; Yokota et al., 2019). Nowadays, terrestrial geodesy has greatly facilitated low-cost and real-time positioning and near-real-time atmosphere state sensing due to positioning model advances (Torge & Müller, 2012), but this has not been achieved in seafloor geodesy. One of important reasons for this is that the high-precision seafloor geodetic positioning seriously relies on the Sound Speed Profile (SSP) measurement in field.

全球导航卫星系统(GNSS)-声学(GNSS-A)定位技术已成为海底大地测量和海底近海区域地壳变形应用的重要工具(Bürgmann & Chadwell,2014;Iinuma et al., 2021)。GNSS-A 定位技术由 Fred Spiess (Spiess, 1985;Spiess 等人,1998 年),并进一步发展了二十多年(Chadwell & Sweeney,2010 年;Chadwell et al., 1997)。区域海底大地测量网络在过去就已经建立起来了(Poutanen & Rózsa, 2020;Yang et al., 2020),并为限制构造运动、地壳变形和地震周期提供了关键观测结果(Gagnon & Chadwell, 2007;Gagnon et al., 2005;Iinuma et al., 2021;Kido et al., 2006;Sato et al., 2011)。过去取得的 GNSS-A 技术成就一方面来自观测方案的进步(Kido et al., 2008;Sato et al., 2013;Spiess 等人,1998),另一方面来自声学定位模型的改进(Asada & Yabuki,2006;Fujita 等人,2006 年;Spiess,1980 年;Watanabe 等人,2020 年;Yang & Qin, 2020;Yokota 等人,2019 年)。如今,由于定位模型的进步,陆地大地测量学极大地促进了低成本和实时定位以及近实时大气状态传感(Torge & Müller,2012),但这在海底大地测量学中尚未实现。其中一个重要原因是,高精度海底大地测量严重依赖于现场声速剖面 (SSP) 测量。

The sound speed structure of the ocean water prominently varies from the depth, spatial location and the time (Yokota et al., 2022). Although several global ocean environment observation plans have been in operation (Hayes et al., 1991; Stammer et al., 2003; Zeng et al., 2016), e.g., Array for Real-time Geostrophic Oceanography (Argo) and Transparent Ocean Plan (TOP) (Wu et al., 2020), the current resolution of ocean environment observations, e.g., the Argo observations having a temporal resolution of several days (Roemmich et al., 2009), cannot satisfy the high-precision seafloor geodetic positioning demands; and therefore an in-field Reference SSP (RSSP) measurement is still required. The sound speed can be directly measured or derived from the Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) profiler measurement (Wilson & Wayne, 1960). However, it is still unrealistic to conduct a high-resolution Sound Speed Field (SSF) measurement for GNSS-A positioning because of the huge cost; and therefore GNSS-A positioning technique in the current state of the art adopts a RSSP to perform the seafloor geodetic positioning (Watanabe et al., 2020). For this, the positioning model requires a strong resist ability to remedy the sound speed variation effect of the RSSP.

海水的声速结构因深度、空间位置和时间而异(Yokota et al., 2022)。尽管已经实施了几个全球海洋环境观测计划(Hayes et al., 1991;Stammer 等人,2003 年;Zeng et al., 2016),例如,实时地转海洋学阵列 (Argo) 和透明海洋计划 (TOP)(Wu et al., 2020),目前海洋环境观测的分辨率,例如,Argo 观测具有几天的时间分辨率(Roemmich et al., 2009),无法满足高精度海底大地测量定位需求;因此,仍然需要进行现场参考 SSP (RSSP) 测量。声速可以直接测量或从电导率-温度-深度(CTD)分析器测量中得出(Wilson & Wayne,1960)。然而,由于成本巨大,对 GNSS-A 定位进行高分辨率声速场 (SSF) 测量仍然不现实;因此,当前技术水平下的 GNSS-A 定位技术采用 RSSP 来执行海底大地测量定位(Watanabe 等人,2020 年)。为此,定位模型需要强大的光刻胶能力来补救 RSSP 的声速变化效应。

The acoustic positioning is seriously affected by the sound speed variations (Kido et al., 2008), which is very familiar to the atmosphere variation affecting GNSS positioning (Chen & Herring, 1997). Inspired by this, the Nadir Total Delay (NTD) model which is analogous to the zenith total delay in GNSS was proposed recently (Honsho & Kido, 2017; Honsho et al., 2019). This idea developed in the GNSS-A positioning can be also found in analyzing the sound speed variation for GNSS-A measurements (Kido et al., 2008). Besides NTD model, a generalized GNSS-A positioning model was also developed to correct the effect of the sound speed variation (Watanabe et al., 2020; Yokota et al., 2022). However, this kind of methods can extract only the sound speed variation relative to the in-field SSP.

声学定位受到声速变化的严重影响(Kido 等人,2008),这与影响 GNSS 定位的大气变化非常熟悉(Chen & Herring,1997)。受此启发,最近提出了类似于 GNSS 的天顶总延迟的最低点总延迟(NTD)模型(Honsho & Kido,2017 年;Honsho 等人,2019 年)。在 GNSS-A 定位中开发的这一想法也可以在分析 GNSS-A 测量的声速变化中找到(Kido et al., 2008)。除了 NTD 模型外,还开发了广义 GNSS-A 定位模型来校正声速变化的影响(Watanabe et al., 2020;Yokota 等人,2022 年)。然而,这种方法只能提取相对于场内 SSP 的声速变化。

In fact, the sound speed variation effect was very early studied by the GNSS-A and SSP observations in Hawaii (Osada et al., 2003). Then, the temporal variation inversion based on the RSSP was developed to eliminate this kind of effect (Fujita et al., 2004, 2006; Matsumoto et al., 2008). For more precisely characterizing the sound speed variation, the inversion method based on a 3-order B-spline model was developed in the past (Ikuta et al., 2008), and then Yokota et al. (2019) advanced this method by extracting the first-order and second-order horizontal sound speed gradients to represent more sound speed variation details (Yasuda et al., 2017). Note that, the above-mentioned inversion methods are based on the RSSP. In fact, the sound speed inversion without using the RSSP was also developed in the past (Chen, 2014). Recently, a self-constraint positioning method without the assistance of in-field SSP has also been developed (Zhao et al., 2022). However, without using the in-field SSP it is still hard to achieve a desirable positioning accuracy, e.g., the positioning error of the above self-constraint positioning method is up to 0.54 m. Precise positioning models without the assistance of in-field SSP still need to be developed to reduce the in-field SSP measurement cost, which is the vitally meaningful not only for facilitating the low-cost large-scale and even global seafloor geodesy but also for achieving the real-time seafloor geodetic applications, like nowadays mature GNSS geodesy.

事实上,夏威夷的 GNSS-A 和 SSP 观测很早就研究了声速变化效应(Osada et al., 2003)。然后,开发了基于 RSSP 的时间变化反转来消除这种效应(Fujita et al., 2004, 2006;Matsumoto et al., 2008)。为了更精确地表征声速变化,过去开发了基于 3 阶 B 样条模型的反演方法(Ikuta et al., 2008),然后 Yokota et al.(2019)通过提取一阶和二阶水平声速梯度来表示更多的声速变化细节(Yasuda et al., 2017). 请注意,上述倒置方法都是基于 RSSP 的。事实上,不使用 RSSP 的声速反演在过去也是开发的(Chen, 2014)。最近,还开发了一种无需场内 SSP 辅助的自约束定位方法(Zhao et al., 2022)。然而,如果不使用现场 SSP,仍然难以达到理想的定位精度,例如,上述自约束定位方法的定位误差高达 0.54 m。在没有现场 SSP 帮助的情况下,仍然需要开发精确定位模型以降低现场 SSP 测量成本,这不仅对于促进低成本的大规模甚至全球海底大地测量具有重要意义,而且对于实现实时海底大地测量应用也具有重要意义,就像现在成熟的 GNSS 大地测量一样。

This contribution is to develop a Self-structured Empirical SSP (SESSP) approach to achieve centimeter-precision-level seafloor geodetic three-dimensional positioning. In "Three-parameter empirical SSP" section, a three-parameter Empirical Temperature Profile (ETP) model is proposed to structure an Empirical Sound Speed Profile (ESSP) by using the Del Grosso’s sound speed formula. In "Two-level optimizations on ESSP" section, a novel GNSS-A positioning model based two-level optimizations is proposed, of which the 1st-level optimization is to fix the ETP model parameters, and the 2nd-level optimization is to finally achieve high-precision location regarding the sound speed variations relative to ESSP. In "Experiment results and tests" section, the proposed models are verified by the long-term seafloor geodetic array observations.

这一贡献是开发了一种自结构经验 SSP (SESSP) 方法,以实现厘米级精度的海底大地三维定位。在“三参数经验 SSP”部分中,提出了一个三参数经验温度曲线 (ETP) 模型,以使用德尔格罗索声速公式构建经验声速曲线 (ESSP)。在“ESSP 的两级优化”部分中,提出了一种基于 GNSS-A 定位模型的新型两级优化,其中第一级优化是固定 ETP 模型参数,第二级优化是最终实现相对于 ESSP 的声速变化的高精度定位。在“实验结果和测试”部分,通过长期海底大地测量阵列观测验证了所提出的模型。

Three-parameter empirical SSP

三参数经验 SSP

The horizontal sound speed stratification can be expressed as an exponential SSP with unknowns for applying much of the World’s oceans (Munk, 1974). Besides, an empirical bilinear SSP with four unknown parameters was also proposed and applied in the seafloor geodetic positioning, that is Chen (2014)

水平声速分层可以表示为指数 SSP,对于应用世界上大部分海洋来说,这是未知数(Munk,1974 年)。此外,还提出了一个具有四个未知参数的经验双线性 SSP ,并将其应用于海底大地测量定位,即 Chen ( 2014)

where is the depth, is the unknown parameter vector, is the surface sound speed, is the bilinear break depth, is the sound speed corresponding to the depth , and and are the piecewise gradients of the bilinear function. The unknown parameters can be estimated jointly with the seafloor geodetic station coordinates.

其中 是深度, 是未知参数向量, 是表面声速, 是双线性断裂深度, 是对应于深度 的声速, 和 是双线性函数的分段梯度。未知参数可以与海底大地测量站坐标联合估计。

Chen (2014) pointed out that and were treated knowns for the facilitation of surface sound speed measurement, but this is not so practical in some cases. Note that there are a series of equivalent profiles that can be used to obtain almost the same positioning result (Sun et al., 2019; Zielinski & Geng, 1999), i.e., this is an ill-posed problem widely existed in nonlinear inversion. To obtain a meaningful solution, we should impose a prior information on with a certain uncertainty, see the Table 3. For solving this problem, we however present a novel ESSP by Del Grosso sound speed formula with an ETP as follow

Chen ( 2014) 指出, 和 Treated Known Known for facilitate of Surface Sound Speed Measurement,但这在某些情况下并不那么实用。请注意,有一系列等效的轮廓可用于获得几乎相同的定位结果(Sun 等人,2019 年;Zielinski & Geng, 1999),即这是一个广泛存在于非线性反演中的病态问题。为了获得有意义的解决方案,我们应该对 具有一定不确定性的先验信息施加,见表 3。然而,为了解决这个问题,我们提出了一种新颖的 ESSP by Del Grosso 声速公式,其 ETP 如下

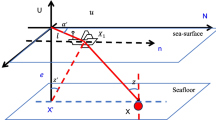

where is an unknown parameter vector of ETP to be jointly estimated with the seafloor geodetic station coordinates, is the corresponding coefficient matrix, represents the intermediate overmeasurement, represents the temperature difference between the sea-surface and sea-bottom, represents the depth of the thermocline, see Fig. 1. The and can be statistically induced from the long-term ocean environment observations and thereby we can impose prior constraints on the parameter estimation.

其中 是要与海底大地测量站坐标联合估计的 ETP 的未知参数向量, 是相应的系数矩阵, 表示中间超测, 表示海面和海底的温度差, 表示温跃层的深度,见图 1。和 可以从长期海洋环境观测中统计推断出来,因此我们可以对参数估计施加先验约束。

As shown in Fig. 1, the three parameters , and to be estimated are the control parameters of the ETP shape. Note that the deep-sea bottom water temperature is generally very stable, for which it is convenient to impose a priori knowledge or constraint on the model parameter . Besides, the deep-sea water temperature will decrease 1–2 °C per 1000 m, which might also be useful to characterize the ETP. Then, substituting ETP (2) and the average salinity S = 35‰ into the Del Grosso formula (Grosso, 1974; Wong & Zhu, 1995), we can establish an ESSP as

如图 1 所示,三个参数 和 待估计 是 ETP 形状的控制参数。注意,深海海底水温一般都很稳定,方便对模型参数 施加先验知识或约束。此外,海洋深水温度每 1000 m 将降低 1–2 °C,这也可能有助于表征 ETP。然后,将 ETP ( 2) 和平均盐度 S = 35‰ 代入 Del Grosso 公式(Grosso,1974 年;Wong & Zhu, 1995),我们可以将 ESSP 建立为

where is ESSP,

其中 是 ESSP,

is a constant associated with the salinity S, is the constant term in the Del Grosso formula,

是与盐度 S 相关的常数, 是 Del Grosso 公式中的常数项,

is the sound speed variation associated with the pressure P which is recommended to use the Leroy’s formula as Leroy and Parthiot (1998)

是与压力 P 相关的声速变化,建议使用 Leroy 公式,如 Leroy 和 Parthiot ( 1998)

where is the latitude,

其中 是纬度,

is the sound speed variation determined by the water temperature T and the temperature-depth mixture terms.

是由水温 T 和温度-深度混合物项确定的声速变化。

With S = 35‰, we can then figure out the coefficients of Eqs. (3), (4), (5), (7) and they are given in Table 1 for facilitating the calculation. Finally, for an arbitrary latitude specified we can figure out the ESSP by employing the data in Table 1.

当 S = 35‰ 时,我们可以计算出 Eqs 的系数。( 3)、( 4)、( 5)、 ( 7) 中给出,它们列于表 1 中,以便于计算。最后,对于指定的任意纬度,我们可以通过使用表 1 中的数据来计算 ESSP。

表 1 ESSP 系数

As the proposed ESSP regards the sound speed variation with hydrostatic pressure of the water that implied in the Leroy’s formula and the water temperature’s exponential decaying characteristic with the depth that implied in the proposed empirical temperature profile, it is more meaningful and accurate to perform the SSP inversion result. We can also use other sound speed formulae to structure the ESSP complying with their applicable conditions, e.g., Wilson formula (Wilson, 1960) and Chen-Millero formula (Chen & Millero, 1977). In the following section, we will propose an optimization approach to determine the model parameters of ETP (2).

由于所提出的 ESSP 考虑了 Leroy 公式中隐含的水的声速随静水压力的变化以及所提出的经验温度剖面中隐含的水温与深度的指数衰减特性,因此执行 SSP 反演结果更有意义和准确。我们还可以使用其他声速公式来构建符合其适用条件的 ESSP,例如,Wilson 公式(Wilson,1960)和 Chen-Millero 公式(Chen & Millero,1977)。在下一节中,我们将提出一种优化方法来确定 ETP 的模型参数 (2)。

Two-level optimizations on ESSP

ESSP 上的两级优化

Overall Scheme 整体方案

Next, we will conduct a joint estimation of ESSP parameters and the seafloor geodetic station coordinates by employing the 1st-level optimization as shown in Fig. 2, which is called as sound speed self-structured empirical SSP approach for its independence on the in-field SSP measurement.

接下来,我们将采用如图 2 所示的一级优化,对 ESSP 参数和海底大地测量站坐标进行联合估计,这被称为声速自结构化经验 SSP 方法,因为它独立于现场 SSP 测量。

As shown in Fig. 2, the 1st-level optimization is performed in the context of the ray-tracing positioning procedure while the 2nd-level one is performed by B-splines for characterizing acoustic delay caused by the sound speed variations relative to ESSP.

如图 2 所示,第一级优化是在射线追踪定位程序的背景下进行的,而第二级优化是由 B 样条执行的,用于表征由相对于 ESSP 的声速变化引起的声学延迟。

The 1st-level optimization

第一级优化

GNSS-A positioning is achieved by a combination of the sea-surface GNSS positioning with the precise acoustic round-trip time measurement from the sea-surface acoustic transducer to the seafloor acoustic transponder (Asada & Yabuki, 2006). Due to the horizontal density stratification of the ocean, the seafloor geodetic positioning generally uses the ray-tracing positioning model. For taking place of the high-cost in-field SSP measurement, we use ESSP to perform a joint estimation of and the seafloor geodetic coordinates. This time that the GNSS-A positioning model reads

GNSS-A 定位是通过结合海面 GNSS 定位和从海面声学换能器到海底声学转发器的精确声学往返时间测量来实现的(Asada & Yabuki, 2006)。由于海洋的水平密度分层,海底大地定位一般采用射线追踪定位模型。为了进行高成本的现场 SSP 测量,我们使用 ESSP 对海底大地坐标进行联合估计 。这一次,GNSS-A 定位模型读取

where is the ith round-trip time observation, is the seafloor transponder coordinate vector to be estimated, is the random error of observation. represents calculated the ith round-trip time,

其中 是第 i 个往返时间观测, 是要估计的海底应答器坐标向量, 是观测的随机误差。 表示计算的第 i 次往返时间,

is one half of the round-trip travelling time calculated by the Two Dimensional (2D) ray-tracing model (Spiess, 1980), are depths of the transducer and transponder, respectively. Note that, horizontal coordinates of transponder are implied in the incident angle of the ith ray calculated by the inversion of the eigenray (Yang et al., 2021).

是由二维 (2D) 光线追踪模型 (Spiess, 1980) 计算的往返旅行时间的一半, 分别是换能器和应答器的深度。请注意,应答器的水平坐标隐含在由特征射线反转计算的第 i 条射线的入射角 中(Yang 等人,2021 年)。

For n observations we have an over-determined vector-form observation equation solved by the nonlinear least squares (LS) criterion reads:

对于 n 个观测值,我们有一个由非线性最小二乘法 (LS) 准则 求解的超定向量形式观测方程 ,如下所示:

where is the weighted sum of the squared residuals, is the residual vector, and and are the variance of observations and prior unit weight variance, respectively. is the weight matrix of observations where is the weight of the ith observation and is the corresponding elevation angle, respectively. Hereafter, we however adopt an equal weight matrix to simplify the discussion, i.e., . To obtain LS solution we get the following first-order partial derivatives of , that is

其中 是残差平方和的加权和, 是残差向量, 和 分别是观测值的方差和先验单位权重方差。 是观测值的权重矩阵,其中 是第 i 个观测值的权重,分别 是相应的仰角。然而,在下文中,我们采用一个等权重矩阵来简化讨论,即 。为了获得 LS 解,我们得到以下 的一阶偏导数 ,即

where 哪里

is the Jacobian matrix of the nonlinear observation about the coordinate vector, is the sound speed at the depth of the transponder, are the azimuth angle and incident angle of the ith ray, respectively.

是非线性观测关于坐标矢量的雅可比矩阵, 是应答器深度处的声速, 分别是第 i 条射线的方位角和入射角。

is the first-order derivative of the round-trip time about . is hardly analytically given but it can be numerically solved. Then, vanishing , i.e., we have

是往返时间 关于 的一阶导数。 很难分析给出,但可以用数值求解。然后,消失 ,即我们有

that can be used to obtain the LS solution. With initial values , if is positively defined, then LS solution can be locally solved by Newton’s method with the second-order partial derivative of , that reads (Xue et al., 2014):

可用于获取 LS 解。对于初始值 ,如果 是正定义的,则 LS 解可以通过牛顿方法局部求解,该方法具有 的二阶偏导数 ,如下所示(Xue et al., 2014):

where , , and k is the iteration index,

其中 , , 和 k 是迭代索引,

in which is the first-order derivative of the ith row of , i.e., the Hessian matrix of the round-trip time about ,

其中 是 的第 i 行 的一阶导数 ,即往返时间 约为 的 Hessian 矩阵

in which is the first-order derivative of the ith row of , i.e., the Hessian matrix of the round-trip time about . Note that, and can be ignored for long-distance or small-residual cases, and at this time we recommend using Gauss–Newton iterative formula as

其中 是 的第 i 行 的一阶导数 ,即往返时间 约为 的 Hessian 矩阵。请注意, 对于长距离或小残差情况,可以忽略 and ,此时我们建议使用高斯-牛顿迭代公式 as

which is recommended to be terminated under the condition where is a sufficient small positive value, i is the index of the S seafloor geodetic stations. It is generally necessary to introduce a certain number of constraints on partial parameters to stabilize the iteration or to obtain a meaningful solution.

建议在足够小的正值的情况下终止 ,i 是 S 海底大地测量台站的索引。通常需要对 partial 参数引入一定数量的约束,以稳定迭代或获得有意义的解决方案。

Next, we impose a priori constraints on . The first a priori constraint can be structured by the temperature stability of the seawater-bottom, that is

接下来,我们对 施加先验约束 。第一个先验约束可以由海水底部的温度稳定性构成,即

where is the depth of the seafloor geodetic station, the error represents the uncertainty of the a priori seawater-bottom temperature. Note that because deep-sea temperature is generally quite stable, the average temperature of the seawater bottom can be easily obtained by global ocean environment observations.

其中 是海底测地测站的深度,误差 表示先验海水底部温度的不确定性。请注意,由于深海温度通常相当稳定,因此可以通过全球海洋环境观测轻松获得海水底部的平均温度。

Let be the variance of , we can structure the following LS criterion

设 是 的方差 ,我们可以构建以下 LS 准则

where is the parameter vector to be estimated. Omitting the deduction, we can obtain the Gauss–Newton iterative formula as

其中 是要估计的参数向量。省略推导,我们可以得到高斯-牛顿迭代公式为

which is recommended to use the same termination condition. It is generally hard to obtain a global or meaningful solution of the problem without an effective initial value.

建议使用相同的终止条件。如果没有有效的初始值,通常很难获得问题的全局或有意义的解决方案。

For most cases an arbitrary guess value of the unknown is sufficient to start the iteration, but we still recommend using a coarse grid search approach to obtain a robust initial value. Let and be the initial value and the variance of , respectively, at this time we can structure the following LS criterion

在大多数情况下,未知 数的任意猜测值足以开始迭代,但我们仍然建议使用粗略网格搜索方法来获得稳健的初始值。设 和 分别为 的初值和方差 ,此时我们可以构建以下 LS 准则

Omitting the deduction, we can write out the Gauss–Newton iterative formula as

省略推导,我们可以将高斯-牛顿迭代公式写为

The sea-surface temperature has a great fluctuation throughout the year, and thereby we recommend a very loose constraint on the parameter .

海面温度全年波动很大,因此我们建议对 parameter 进行非常宽松的约束。

It is notable that Newton-type methods are of local convergence and may seriously suffer from ill-posedness of the problem, e.g., the non-uniqueness of the nonlinear parameter , and therefore it is recommended to be found out by a grid search method. In fact, the LS solution of (23) can be treated as a function about the variable because of and it is denote as .

值得注意的是,牛顿型方法具有局部收敛性,可能会严重受到问题的病态性影响,例如非线性参数 的非唯一性,因此建议通过网格搜索方法找出。事实上,( 23) 的 LS 解 可以被视为关于变量 的函数,因为 ,它表示为 。

The algorithm is given in Fig. 3.

该算法如图 3 所示。

Note that are linear parameters for (2) but they are nonlinear parameters both for (3) and (8), and therefore must be iteratively solved.

请注意, ( 2) 是线性参数,但它们是 ( 3) 和 ( 8) 的非线性参数,因此必须迭代求解。

The 2nd-level optimization

第 2 级优化

Next, we will take the ESSP derived from the 1st-level optimization as a RSSP to conduct the precise positioning. Regarding the N and E direction variations and temporal variation of the sound speed, we can express the Four Dimensional (4D) SSF to be the form as

接下来,我们将 1st level 优化 得出的 ESSP 作为 RSSP 进行精确定位。关于声速的 N 和 E 方向变化和时间变化,我们可以将四维 (4D) SSF 表示为以下形式

where is the ESSP obtained from the 1st-level optimization, are sound speed gradients of the SSF relative to RSSP.

其中 是从第一级优化 获得的 ESSP, 是 SSF 相对于 RSSP 的声速梯度。

It is very familiar to the sound speed inversion in the 1st-level optimization that the spatiotemporal sound speed gradients can be jointly estimated with the seafloor geodetic coordinates. With “Appendix 1” we can directly write out the positioning model regarding the three sound speed gradients, that is

与一级优化中的声速反演非常熟悉的是,时空声速梯度可以与海底大地坐标联合估计。使用“附录 1”,我们可以直接写出关于三个声速梯度的定位模型,即

where t is the travel time observation,

其中 t 是旅行时间观测值,

is the mapping function, and are the zenith angle and azimuth angle of the sea-surface platform observed at the seafloor geodetic station, respectively; and are the zenith angle and azimuth angle observed at the seafloor geodetic network array center, respectively.

是制图函数, 分别是在海底大地测量站观测到的海面平台的天顶角和方位角; 和 分别是在海底大地测量网络阵列中心观测到的天顶角和方位角。

are the five zenith delays, can be defined as the measure of the ray bending degree. To characterize the five time-varying zenith delay parameters , the following B-splines

是 5 个 Zenith 延迟, 可以定义为光线弯曲度的度量。为了表征 5 个时变天顶延迟参数 ,以下 B 样条曲线

are recommended, is the unknown model parameter vector to be estimated, is the coefficient of the qth k-degree B-spine basis function . This indicates the observation time span is split into intervals of which the knots span is where is the observation time span. If it is not especially specified, the subscript will be omitted in the following discussion.

是要 估计的未知模型参数向量, 是第 q k 度 B-spine 基函数 的系数。这表示观测时间跨度被划分为 多个间隔,其中 knots 跨度是 其中 是观测时间跨度。如果没有特别指定,在下面的讨论中将省略下标 。

At this stage, considering the smooth nature of the physical ocean process signal, we can conduct a series of 2-order smooths on the sound speed variations, and therefore we can alternatively use the optimization criterion as follow

在这个阶段,考虑到物理海洋过程信号的平滑性质,我们可以对声速变化进行一系列的 2 阶平滑,因此我们可以交替使用优化准则,如下所示

where is the second-order derivative of about the time,

其中 是大约时间的 二阶导数,

is the squared norm of the estimated signal , where and are the starting time and end time of the observation, respectively, which is defined by the inner product of and , is the scale factor of the space specified by the above inner produce, which can be defined as

是估计信号 的平方范数 ,其中 和 分别是观测的开始时间和结束时间,由 和 的内积定义, 是上述内积 指定的空间的比例因子,可以定义为

where represents the variance of the random signal .

其中 表示随机信号 的方差 。

To connect the minimization (29) with the normal form (20) of LS with constraints, we can rewrite (30) into the form as

要将 LS 的最小化 ( 29) 与带有约束的 LS 的范式 ( 20) 连接起来,我们可以将 ( 30) 改写为

where 哪里

of which 其中

is the weight matrix. Then, Omitting the deduction, we can immediately write out the Gauss–Newton solution of (29). To save the space, we write the Gauss–Newton solution only with the first three zenith delays, that is

是权重矩阵。然后,省略推导,我们可以立即写出 ( 29) 的高斯-牛顿解。为了节省空间,我们只编写前三个天顶延迟的高斯-牛顿解,即

where is the design matrix of the parameter . The above formula can be easily extended for estimating the five zenith delays. Note that hyperparameter might be optimally determined by the cross-test method or AIC criterion, but hereafter we set them to be zeros.

其中 是参数 的设计矩阵 。上述公式可以很容易地扩展以估计五个天顶延迟。请注意,超参数 可能由交叉测试方法或 AIC 标准最佳确定,但此后我们将它们设置为零。

Experiment results and tests

实验结果和测试

Experimental data 实验数据

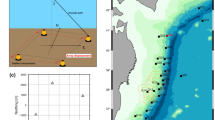

The test adopts Japanese seafloor geodetic network array MYGI to verify the proposed GNSS-A positioning models. The observation span of the opened MYGI station data is from 2011 to 2020, having 35 repeated observations. The long-term displacement time series solution facilitates the positioning accuracy verification based on the fact the station has a linear motion trend with the tectonic movement of the plate (Fig. 4).

该测试采用日本海底大地测量网络阵列 MYGI 对所提出的 GNSS-A 定位模型进行了验证。已打开的 MYGI 站数据的观测跨度为 2011 年至 2020 年,共 35 次重复观测。长期位移时间序列解决方案有助于根据站与板块构造运动呈线性运动趋势的事实进行定位精度验证(图 4)。

We take the GNSS-Acoustic Ranging combined POsitioning Solver (GARPOS V1.0.0) software output as an external reference solution to evaluate the propose models. The GARPOS software adopts the recommended default parameter settings.

我们采用 GNSS-Acoustic Ranging 组合定位求解器 (GARPOS V1.0.0) 软件输出作为外部参考解决方案来评估所提出的模型。GARPOS 软件采用推荐的默认参数设置。

1st-level optimization results

第一级优化结果

Prior temperatures from Argo observation

Argo 观测的先前温度

We collected Argo observations around MYGI within an area of 110,889 km2, lying within the interval [(142.9167° ± 1.5°) E, (38.0833° ± 1.5°) N], from March 28, 2011 to June 15, 2020, see Fig. 5. It shows that the sea-surface temperature has a very large fluctuation, but the seawater bottom temperature is very stable. It is also hard to precisely fix the thermocline depth which lies within the interval (300 m 500 m).

我们收集了 2011 2 年 3 月 28 日至 2020 年 6 月 15 日期间 [(142.9167° ± 1.5°) E, (38.0833° ± 1.5°) N] 区间内的 MYGI 周围 Argo 观测数据,见图 5。它表明海面温度有很大的波动,但海水底部温度非常稳定。也很难精确确定位于间隔(300 m 500 m)内的温跃层深度。

The depth of MYGI station plots about 1727.8 m. the probability distribution of seawater bottom temperature at this depth in Fig. 6. It shows that, the mean of the seawater bottom temperature is 2.15 and STD is 0.09 . Therefore, we adopt the 1st-level optimization parameter settings in Table 2. The same method is used to analyze the seawater bottom sound speed.

MYGI 站的深度约为 1727.8 m。图 6 中该深度的海水底部温度概率分布。它表明,海水底部温度的平均值为 2.15,STD 为 0.09 。因此,我们采用表 2 中的第一级优化参数设置。同样的方法用于分析海水海底声速。

表 2 ESSP 一级优化参数设置

The parameter settings of 1st-level optimization on bilinear SSP are given in Table 3. We impose lose constraints on the surface sound speed and the two sound speed gradients. Like constraining the bottom water temperature of ESSP, the bottom sound speed is imposed with a tight constraint 1486.62 m/s with the STD 0.01 m/s.

表 3 给出了双线性 SSP 上一级优化的参数设置。我们对表面声速和两个声速梯度施加了损失约束。与限制 ESSP 的底部水温一样,底部声速受到 1486.62 m/s 的严格约束,STD 为 0.01 m/s。

表 3 双线性 SSP 一级优化参数设置

SSP inversion precision analysis

SSP 反演精度分析

The SSP inversion results are compared with the in-field SSP and they are given in Fig. 7. It shows that the SSP inversions can overall characterize the shape of the in-field SSP, but it is hard to precisely fit the sea-surface sound speed. To precisely reflect the SSP inversion precision we adopt three piece-wise statistics, see Fig. 8.

将 SSP 反演结果与场内 SSP 进行了比较,如图 7 所示。结果表明,SSP 反演可以总体表征场内 SSP 的形状,但很难精确拟合海面声速。为了精确反映 SSP 反演精度,我们采用三分段统计,见图 8。

Figure 8 shows that both for the bilinear SSP and ESSP the sound speed inversion precision increases with the depth, e.g., for the proposed ESSP, the mean bias and STD of the inversion sound speed in deepwater are 0.085 m/s and 2.448 m/s respectively, but those in the shallow water are up to 2.455 m/s and 10.862 m/s respectively. Table 4 shows that the inversion precision of proposed ESSP is overall better than that of the bilinear SSP even though the bilinear SSP has a relatively small bias for whole water column. Note that it is hard to avoid a bias in the inversion SSP relative to the in-field SSP.

图 8 表明,对于双线性 SSP 和 ESSP 的声速反演精度都随着深度的增加而增加,例如,对于所提出的 ESSP,深水反演声速的平均偏差和 STD 分别为 0.085 m/s 和 2.448 m/s,而浅水的反演声速分别高达 2.455 m/s 和 10.862 m/s。表 4 显示,所提出的 ESSP 的反演精度总体上优于双线性 SSP,尽管双线性 SSP 对整个水柱的偏差相对较小。请注意,很难避免反转 SSP 相对于场内 SSP 的偏差。

表 4 反转 SSP 的平均偏差和 STD

Positioning precision analysis

定位精度分析

We adopt the Argo SSP nearby MYGI station and the inversion SSPs to perform the positioning. Taking the positioning result based on the in-field SSP as a reference, we can then figure out the positioning errors caused by the substitutions of the in-field SSP and they given in Fig. 9. It shows that the Argo SSP solution has a relatively large positioning error especially in the vertical direction, but the solutions based on the inversion SSPs are almost same with each other.

我们采用 MYGI 站附近的 Argo SSP 和反转 SSP 进行定位。以基于场内 SSP 的定位结果为参考,我们可以计算出场内 SSP 替换引起的定位误差,如图 9 所示。结果表明,Argo SSP 解具有比较大的定位误差,尤其是在垂直方向上,但基于反演 SSP 的解彼此几乎相同。

The bias and STD of the positioning error series in Fig. 9 are figured out and they are given in Table 5. It shows that both the proposed ESSP solution and bilinear SSP can achieve decimeter-level-precision positioning, e.g., the positional error of the proposed ESSP solution for each coordinate component doesn’t exceed 0.4 m, but there are biases 0.003 m and − 0.016 m in E direction and N direction, respectively. The vertical bias of proposed ESSP solution is smaller than that of the bilinear SSP solution and they are − 0.219 m and − 0.260 m, respectively, but their horizontal biases can be considered at the same order for centimeter-precision-level positioning. Although the bilinear SSP inversion precision is significantly lower than that the proposed ESSP, both the bilinear SSP solution and the proposed ESSP solution possess almost the same residual with the in-field SSP solution, see Fig. 10. This indicates that the two inversion SSPs are approximately equivalent to each other for the geodetic positioning application. This also shows that imposing a prior knowledge about the sound speed on the inversion is vitally important to obtain a meaningful SSP inversion solution.

图 9 中定位误差序列的偏置和 STD 已计算出来,它们在表 5 中给出。结果表明,所提出的 ESSP 解和双线性 SSP 都可以实现分米级精度定位,例如,所提出的 ESSP 解对每个坐标分量的位置误差不超过 0.4 m,但在 E 方向和 N 方向分别存在 0.003 m 和 − 0.016 m 的偏差。所提出的 ESSP 解决方案的垂直偏差小于双线性 SSP 解决方案的垂直偏差,它们分别为 -0.219 m 和 -0.260 m,但它们的水平偏差可以以相同的顺序进行厘米精度级定位。尽管双线性 SSP 反演精度明显低于所提出的 ESSP,但双线性 SSP 解和所提出的 ESSP 解都具有与场内 SSP 解几乎相同的残差,见图 10。这表明对于大地测量定位应用程序,两个反演 SSP 彼此大致等效。这也表明,在逆温上施加有关声速的先验知识对于获得有意义的 SSP 逆温解至关重要。

表 5 基于不同 SSP 的解的定位误差比较

2nd-level optimization results

第 2 级优化结果

We use the parameter settings in Table 6 for performing the 2nd-level optimization. Note that the positioning accuracy may be further improved by optimally selecting the knots span and the smooth factor .

我们使用表 6 中的参数设置来执行第二级优化。请注意,通过最佳选择节长 和平滑因子 ,可以进一步提高定位精度。

表 6 二级优化参数设置

The above empirical parameter settings listed in Table 6 will be further validated in following page.

表 6 中列出的上述经验参数设置将在下一页中进一步验证。

The positioning results based on the 2nd-level optimization are given in Fig. 11. It shows that the E and N coordinate biases existing in the 1st-level optimization have been removed at a great extent.

基于 2 级优化的定位结果如图 11 所示。这表明 1 级优化中存在的 E 和 N 坐标偏差在很大程度上被去除了。

Table 7 shows that the horizontal precision of 2nd-level optimization for ESSP is better than 3 mm, while the vertical precision is better than 3 cm. The horizontal positioning accuracy of ESSP is very close to that of bilinear SSP, but vertical STD of ESSP solution is 0.0238 m which is significantly smaller than that 0.0433 m of bilinear SSP solution. Further considering the positioning error of the reference solution based on the in-field SSP, we can draw the conclusion that the proposed two-level optimization approach can achieve almost the same horizontal positioning precision with that based on in-field SSP. This conclusion becomes more solid when making a comparison among the 2nd-level optimization residuals of different SSP solutions as shown in Fig. 12. It also shows that the residuals are sharply shrunk after applying the 2nd optimization, compare to Fig. 9. A special attention on an existing bias about 1 cm in the vertical direction needs to be paid in future studies.

表 7 显示,ESSP 的二级优化的水平精度优于 3 mm,而垂直精度优于 3 cm。ESSP 的水平定位精度与双线性 SSP 非常接近,但 ESSP 解的垂直 STD 为 0.0238 m,明显小于双线性 SSP 解的 0.0433 m。进一步考虑基于场内 SSP 的参考解的定位误差,我们可以得出结论,所提出的两级优化方法可以实现与基于场内 SSP 的水平定位精度几乎相同的水平定位精度。当对不同 SSP 解决方案的 2 级优化残差进行比较时,这个结论变得更加可靠,如图 12 所示。它还显示,与图 9 相比,在应用第二次优化后,残差急剧缩小。在未来的研究中,需要特别注意垂直方向上约 1 cm 的现有偏差。

表 7 一级优化和二级优化精度对比

Long-term displacement time series analysis

长期位移时间序列分析

Let be the undetermined array geometry to perform the rigid-array fixed solution, be the positional difference of the array center for kth-epoch observation, and they can be determined by solving the equation as (Watanabe et al., 2020):

设 为执行刚阵列固定解的未确定数组几何结构, 为 k 个纪元观测的数组中心的位置差,它们可以通过求解方程来确定,如下所示(Watanabe et al., 2020):

where, if the transponder j is used in th observation, . In addition, . where w and are the number of transponders and epochs, respectively, and denotes the transponders’ position at the kth-epoch.

其中,如果应答器 j 用于 th 观测,则 。此外, .其中 w 和 分别是应答器和纪元的数量,表示 应答器在第 k 纪元的位置。

The long-term displacement time series obtained by (36) is plotted in Fig. 13. The GARPOS solution time series based on in-field SSP as an external reference is also plotted in Fig. 13 for conducting the comparison. Then, we can use the linear model x(t) = x0 + vt + e where x is the displacement time series and v is the velocity to fit the displacement time series to verify the proposed approach. The LS fitting residual as an estimation of the observation error e can be then used to evaluate the positioning precision.

由 ( 36) 获得的长期位移时间序列绘制在图 13 中。图 13 中还绘制了基于现场 SSP 作为外部参考的 GARPOS 解决方案时间序列,以便进行比较。然后,我们可以使用线性模型 x(t) = x 0 + vt + e,其中 x 是位移时间序列,v 是拟合位移时间序列的速度来验证所提出的方法。然后,可以使用 LS 拟合残差作为观测误差 e 的估计值来评估定位精度。

Figure 13 shows that the proposed 2nd-level optimization approach can produce almost the same station movement trend as the GARPOS solutions, and more detailed information about the time series residuals is given in Table 8.

图 13 显示,所提出的 2 级优化方法可以产生与 GARPOS 解决方案几乎相同的台站移动趋势,表 8 中给出了有关时间序列残差的更多详细信息。

表 8 位移时间序列分析结果

Table 8 shows that the largest difference among the station velocities along E, N, U directions is about 5.5 mm/a and it happens in the U direction. The horizontal displacement time series residual STDs of proposed models are close to that of GARPOS model. The influence of the substitution of the in-field SSP with the self-structured ESSP on the station velocity estimation are 0.0, 0.4 and − 1.4 mm/a in E, N, U directions, respectively, which can be ignored in applying GNSS-A to the seafloor geodesy in the current state of the art. We can draw almost the same conclusion for apply the bilinear SSP to the seafloor geodetic positioning. It is a very interesting but important that for seafloor geodetic positioning at centimeter precision and long-term tectonic displacement monitoring in-field SSP measurements might be unnecessary. However, as an extra product the SSP inversion should keep its physical meaning by imposing a prior knowledge, such as the hydrostatic pressure of the water and the water temperature’s exponential decaying characteristic with the depth.

表 8 显示,沿 E、N、U 方向的站点速度之间的最大差异约为 5.5 mm/a,并且发生在 U 方向。所提模型的水平位移时间序列残差 STD 与 GARPOS 模型的水平位移时间序列残差 STD 接近。用自结构 ESSP 替换场内 SSP 对台站速度估计的影响在 E、N、U 方向分别为 0.0、0.4 和 − 1.4 mm/a,在当前技术水平下将 GNSS-A 应用于海底大地测量时可以忽略不计。对于将双线性 SSP 应用于海底大地测量定位,我们可以得出几乎相同的结论。对于厘米级精度的海底大地定位和长期的构造位移监测,现场 SSP 测量可能没有必要,这是一个非常有趣但很重要的事情。然而,作为一个额外的产品,SSP 反演应该通过施加先验知识来保持其物理意义,例如水的静水压力和水温随深度的指数衰减特性。

Remarks and conclusions 备注和结论

High-cost in-field SSP measurements have prevented GNSS-A from global seafloor geodesy, especially for real-time applications. The proposed self-structured SSP (SSSP) approach is a useful way to facilitate GNSS-A for conducting the large-scale and even global seafloor geodetic positioning.

高成本的现场 SSP 测量使 GNSS-A 无法进行全球海底大地测量,尤其是对于实时应用。所提出的自结构 SSP (SSSP) 方法是促进 GNSS-A 进行大规模甚至全球海底大地定位的有用方法。

The overall shape of the in-field SSP can be characterized by the proposed three-parameter empirical temperature profile by performing a joint estimation of the three parameters with the seafloor geodetic coordinates. However, the global optimal solution of the thermocline depth parameter is hard to be obtained in the context of the Gauss–Newton method because of its non-uniqueness and local convergence, and therefore the grid search method is recommended to be used. The seawater bottom temperature might also face with ill-posed problems, but fortunately the seawater bottom temperature prior constraint can be easily structured by the history ocean environment observations or by the current ocean temperature knowledge because of its stability.

通过与海底大地坐标对三个参数进行联合估计,可以通过提出的三参数经验温度剖面来表征场内 SSP 的整体形状。然而,由于温跃层深度参数的非唯一性和局部收敛性,在高斯-牛顿方法的背景下很难获得温跃层深度参数的全局最优解,因此建议使用网格搜索方法。海水海底温度也可能面临病态问题,但幸运的是,由于其稳定性,可以很容易地通过历史海洋环境观测或当前海洋温度知识来构建海水海底温度先验约束。

The inaccuracy of the self-structured SSP can be almost completely absorbed by the proposed 2nd-level optimization such that it can achieve almost the same positioning result as that based on the in-field SSP. The influence of substituting the in-field SSP with the proposed SSSP on the horizontal positioning is less than 3 mm while that on the vertical positioning is better than 3cm in the STD sense. The influence of the substitution of the in-field SSP with the self-structured SSP on the station velocity estimation are further reduced to be omitted for applying GNSS-A to the seafloor geodesy in current state of the art. Sound speed inversion accuracy of the proposed SSSP is more accurate than the bilinear SSP and this leads to a more accurate vertical positioning precision.

自结构 SSP 的不精确性几乎可以完全被所提出的第二级优化所吸收,从而可以获得与基于场内 SSP 几乎相同的定位结果。用建议的 SSSP 代替场内 SSP 对水平定位的影响小于 3 mm,而对垂直定位的影响在 STD 意义上优于 3 cm。在当前技术水平下,将 GNSS-A 应用于海底大地测量时,用自结构 SSP 替换场内 SSP 对台站速度估计的影响进一步减少,从而省略。所提出的 SSSP 的声速反转精度比双线性 SSP 更准确,这导致了更准确的垂直定位精度。

Availability of data and materials

数据和材料的可用性

All experimental data can be obtained through the open-source website https://www1.kaiho.mlit.go.jp/KOHO/chikaku/kaitei/sgs/datalist.html

所有实验数据均可通过开源网站获取 https://www1.kaiho.mlit.go.jp/KOHO/chikaku/kaitei/sgs/datalist.html

References 引用

Asada, A., & Yabuki, T. (2006). Centimeter-level positioning on the seafloor. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, 77(1), 7–12.

Asada, A., & Yabuki, T. (2006 年)。海底厘米级定位。日本科学院学报,77(1),7-12。Bürgmann, R., & Chadwell, D. (2014). Seafloor geodesy. Annual Review of Earth & Planetary Ences, 42(1), 509–534.

Bürgmann, R., & Chadwell, D. (2014 年)。海底大地测量学。地球与行星年鉴, 42(1), 509–534.Chadwell, C. D., Spiess, F. N., Hildebrand, J. A., Young, L. E., Purcell, G. H., & Dragert, H. (1997). Sea floor strain measurement using GPS and acoustics. In J. Segawa, H. Fujimoto, & S. Okubo (Eds.), Gravity, geoid and marine geodesy (pp. 682–689). Springer.

Chadwell, C. D., Spiess, F. N., Hildebrand, J. A., Young, L. E., Purcell, G. H., & Dragert, H. (1997).使用 GPS 和声学进行海底应变测量。在 J. Segawa, H. Fujimoto, & S. Okubo (Eds.), 重力、大地水准面和海洋大地测量学 (pp. 682–689).斯普林格。Chadwell, C. D., & Sweeney, A. D. (2010). Acoustic ray-trace equations for seafloor geodesy. Marine Geodesy, 33(2–3), 164–186.

Chadwell, C. D., & Sweeney, A. D. (2010).海底大地测量学的声学射线追踪方程。海洋大地测量学,33(2-3),164-186。Chen, C., & Millero, F. J. (1977). Speed of sound in seawater at high pressures. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 62(5), 1129–1135. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.381646

陈, C., & 米勒罗, FJ (1977)。高压下海水中的声速。美国声学学会杂志,62(5),1129-1135。https://doi.org/10.1121/1.381646Chen, G., & Herring, T. A. (1997). Effects of atmospheric azimuthal asymmetry on the analysis of space geodetic data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 102(B9), 20489–20502.

Chen, G., & Herring, T. A. (1997).大气方位不对称性对空间大地测量数据分析的影响。地球物理研究杂志:固体地球,102(B9),20489–20502。Chen, H. H. (2014). Travel-time approximation of acoustic ranging in GPS/Acoustic seafloor geodesy. Ocean Engineering, 84, 133–144.

陈,HH(2014 年)。GPS/声学海底大地测量学中声学测距的行程时间近似值。海洋工程, 84, 133–144.Del Grosso, V. A. (1974). New equation for the speed of sound in natural waters (with comparisons to other equations). The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 56(4), 1084–1091. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1903388

Del Grosso, V. A. (1974 年)。自然水中声速的新方程(与其他方程的比较)。美国声学学会杂志,56(4),1084-1091。https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1903388Fujita, M., Ishikawa, T., Mochizuki, M., Sato, M., Toyama, S., Katayama, M., et al. (2006). GPS/Acoustic seafloor geodetic observation: Method of data analysis and its application. Earth, Planets and Space, 58(3), 265–275.

Fujita, M., Ishikawa, T., Mochizuki, M., Sato, M., Toyama, S., Katayama, M., et al. (2006)。GPS/声学海底大地测量观测:数据分析方法及其应用.地球、行星和太空,58(3),265-275。Fujita, M., Sato, M., & Yabuki, T. (2004). Development of seafloor positioning software using inverse method. Report of Hydrographic and Oceanographic Researches, 22, 50–56.

藤田,M.,佐藤,M.和矢吹,T.(2004)。使用逆法开发海底定位软件。水文和海洋学研究报告,22,50-56。Gagnon, K. L., & Chadwell, C. D. (2007). Relocation of a seafloor transponder—Sustaining the GPS-Acoustic technique. Earth, Planets and Space, 59(5), 327–336.

Gagnon, K. L., & Chadwell, C. D. (2007)。海底应答器的重新定位 - 维持 GPS 声学技术。地球、行星和太空,59(5),327-336。Gagnon, K., Chadwell, C., & Norabuena, E. (2005). Measuring the onset of locking in the Peru–Chile trench with GPS and acoustic measurements. Nature, 434(7030), 205.

Gagnon, K., Chadwell, C., & Norabuena, E. (2005).使用 GPS 和声学测量测量秘鲁-智利海沟中锁死的开始。自然, 434(7030), 205.Hayes, S., Mangum, L., Picaut, J., Sumi, A., & Takeuchi, K. (1991). TOGA-TAO: A moored array for real-time measurements in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 72(3), 339–347.

海耶斯,S.,曼古姆,L.,皮考特,J.,苏米,A.和竹内,K.(1991)。TOGA-TAO:用于热带太平洋实时测量的系泊阵列。美国气象学会公报,72(3),339-347。Honsho, C., & Kido, M. (2017). Comprehensive analysis of traveltime data collected through GPS-Acoustic observation of seafloor crustal movements. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 122(10), 8583–8599. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JB014733

Honsho, C., & Kido, M. (2017).对通过 GPS 海底地壳运动声学观测收集的旅行时间数据进行综合分析。地球物理研究杂志:固体地球,122(10),8583–8599。https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JB014733Honsho, C., Kido, M., Tomita, F., & Uchida, N. (2019). Offshore postseismic deformation of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake Revisited: Application of an improved GPS-Acoustic positioning method considering horizontal gradient of sound speed structure. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 124(6), 5990–6009.

Honsho, C., Kido, M., Tomita, F., & Uchida, N. (2019).2011 年东北地震的海上震后变形再访:考虑声速结构水平梯度的改进 GPS 声学定位方法的应用。地球物理研究杂志:固体地球,124(6),5990–6009。Iinuma, T., Kido, M., Ohta, Y., Fukuda, T., Tomita, F., & Ueki, I. (2021). GNSS-Acoustic observations of seafloor crustal deformation using a wave glider. Frontiers in Earth Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.600946

饭沼,T.,木户,M.,太田,Y.,福田,T.,富田,F.,和植木,I.(2021)。GNSS-使用波浪滑翔机对海底地壳变形的声学观测。地球科学前沿。https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.600946Ikuta, R., Tadokoro, K., Ando, M., Okuda, T., Sugimoto, S., Takatani, K., et al. (2008). A new GPS-acoustic method for measuring ocean floor crustal deformation: Application to the Nankai Trough. Journal of Geophysical Research. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004875

生田,R.,田所,K.,安藤,M.,奥田,T.,杉本,S.,高谷,K.,等人(2008 年)。一种测量海底地壳变形的新型 GPS 声学方法:在南海槽中的应用。地球物理研究杂志。https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004875Kido, M., Fujimoto, H., Miura, S., Osada, Y., Tsuka, K., & Tabei, T. (2006). Seafloor displacement at Kumano-nada caused by the 2004 off Kii Peninsula earthquakes, detected through repeated GPS/Acoustic surveys. Earth, Planets and Space, 58(7), 911.

Kido, M., Fujimoto, H., Miura, S., Osada, Y., Tsuka, K., & Tabei, T. (2006).2004 年纪伊半岛附近地震引起的熊野滩海底位移,通过反复的 GPS/声学调查检测到。地球、行星和空间,58(7),911。Kido, M., Osada, Y., & Fujimoto, H. (2008). Temporal variation of sound speed in ocean: A comparison between GPS/acoustic and in situ measurements. Earth, Planets and Space, 60(3), 229–234.

Leroy, C. C., & Parthiot, F. (1998). Depth-pressure relationships in the oceans and seas. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 103(3), 1346–1352. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.421275

Matsumoto, Y., Fujita, M., & Ishikawa, T. (2008). Development of multi-epoch method for determining seafloor station position. http://hdl.handle.net/1834/16415

Munk, W. H. (1974). Sound channel in an exponentially stratified ocean, with application to SOFAR. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 55(2), 220–226. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1914492

Osada, Y., Fujimoto, H., Miura, S., Sweeney, A., Kanazawa, T., Nakao, S., et al. (2003). Estimation and correction for the effect of sound velocity variation on GPS/Acoustic seafloor positioning: An experiment off Hawaii Island. Earth, Planets and Space, 10(55), e17–e20. https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03352464

Poutanen, M., & Rózsa, S. (2020). The Geodesist’s handbook 2020. Journal of Geodesy, 94(11), 1–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-020-01434-z

Roemmich, D., Johnson, G. C., Riser, S., Davis, R., Gilson, J., Owens, W. B., et al. (2009). The Argo program: Observing the global ocean with profiling floats. Oceanography, 22(2), 34–43.

Sato, M., Fujita, M., Matsumoto, Y., Saito, H., Ishikawa, T., & Asakura, T. (2013). Improvement of GPS/acoustic seafloor positioning precision through controlling the ship’s track line. Journal of Geodesy, 87(9), 825–842.

Sato, M., Ishikawa, T., Ujihara, N., Yoshida, S., Fujita, M., Mochizuki, M., & Asada, A. (2011). Displacement above the hypocenter of the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Ence, 332(6036), 1395.

Spiess, F. (1980). Acoustic techniques for marine geodesy. Marine Geodesy, 4(1), 13–27.

Spiess, F. (1985). Analysis of a possible sea floor strain measurement system. Marine Geodesy, 9(4), 385–398.

Spiess, F. N., Chadwell, C. D., Hildebrand, J. A., Young, L. E., Purcell, G. H., & Dragert, H. (1998). Precise GPS/Acoustic positioning of seafloor reference points for tectonic studies. Physics of the Earth & Planetary Interiors, 108(2), 101–112.

Stammer, D., Wunsch, C., Giering, R., Eckert, C., Heimbach, P., Marotzke, J., Adcroft, A., Hill, C. N., & Marshall, J. (2003). Volume, heat, and freshwater transports of the global ocean circulation 1993–2000, estimated from a general circulation model constrained by World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE) data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 108(C1), 7.

Sun, W., Yin, X., & Zeng, A. (2019). The relationship between propagation time and sound velocity profile for positioning seafloor reference points. Marine Geodesy, 42(2), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490419.2019.1575938

Torge, W., & Müller, J. (2012). Geodesy. In Geodesy. de Gruyter.

Watanabe, S., Ishikawa, T., Yokota, Y., & Nakamura, Y. (2020). GARPOS: Analysis software for the GNSS-A seafloor positioning with simultaneous estimation of sound speed structure. Frontiers in Earth Science, 8, 508. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2020.597532

Wilson, W. D. (1960). Speed of sound in sea water as a function of temperature, pressure, and salinity. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 32(6), 641–644. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1908167

Wilson, & Wayne, D. (1960). Equation for the speed of sound in sea water. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 32(10), 1357–1357.

Wong, G. S. K., & Zhu, S. (1995). Speed of sound in seawater as a function of salinity, temperature, and pressure. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97(3), 1732–1736. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.413048

Wu, L., Chen, Z., Lin, X., & Liu, W. (2020). Building the integrated observational network of “Transparent Ocean.” Chinese Science Bulletin, 65(25), 2654–2661.

Xue, S., Yang, Y., & Dang, Y. (2014). A closed-form of Newton method for solving over-determined pseudo-distance equations. Journal of Geodesy, 88(5), 441–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-014-0695-y

Yang, W., Xue, S., & Liu, Y. (2021). P-order secant method for rapidly solving the ray inverse problem of underwater acoustic positioning. Marine Geodesy. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490419.2021.1992547

Yang, Y., Liu, Y., Sun, D., Xu, T., & Zeng, A. (2020). Seafloor geodetic network establishment and key technologies. Science China Earth Science, 8(63), 1188–1198.

Yang, Y., & Qin, X. (2020). Resilient observation models for seafloor geodetic positioning. Journal of Geodesy, 95, 1–13.

Yasuda, K., Tadokoro, K., Taniguchi, S., Kimura, H., & Matsuhiro, K. (2017). Interplate locking condition derived from seafloor geodetic observation in the shallowest subduction segment at the Central Nankai Trough, Japan. Geophysical Research Letters, 44(8), 3572–3579.

Yokota, Y., Ishikawa, T., & Watanabe, S. (2019). Gradient field of undersea sound speed structure extracted from the GNSS-A oceanography: GNSS-A as a sensor for detecting sound speed gradien. Marine Geophysical Research, 40(4), 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11001-018-9362-7

Yokota, Y., Watanabe, S., Ishikawa, T., & Nakamura, Y. (2022). Temporal change of km-scale underwater sound speed structure and GNSS-A positioning accuracy. Earth and Space Science Open Archive, 9, e2022EA002224.

Zeng, L., Wang, D., Chen, J., Wang, W., & Chen, R. (2016). SCSPOD14, a South China Sea physical oceanographic dataset derived from in situ measurements during 1919–2014. Scientific Data, 3(1), 1–13.

Zhao, J., Liang, W., Ma, J., Liu, M., & Li, Y. (2022). A self-constraint underwater positioning method without the assistance of measured sound velocity profile. Marine Geodesy. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490419.2022.2079778

Zielinski, A., & Geng, X. (1999). Precise multibeam acoustic bathymetry. Marine Geodesy, 22(3), 157–167.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Hydrographic and Oceanographic Department, Japan Coast Guard providing open seafloor geodetic data for this paper.

Funding

This study was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (41931076), Laoshan Laboratory (LSKJ202205100, LSKJ202205105), and The Special Fund of Chinese Central Government for Basic Scientific Research Operations (AR2115).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Appendix 1: Seafloor geodetic positioning models with five acoustic zenith delays

Appendix 1: Seafloor geodetic positioning models with five acoustic zenith delays

As shown in Fig. 14, without loss of generality, let the origin of NEU coordinate system be the centroid of the seafloor geodetic network array, let the RSSP be at , the first-order Taylor series expansion of SSF at reads

where , , are the partial derivatives about the variable n, e and t, respectively, which represent the gradients of SSF.

As shown in Fig. 14, let and are the azimuth angle and zenith angle of the surface transducer position x, is the seafloor transponder coordinate vector to be estimated, be the depth of the seafloor geodetic station, then SSP at the position x can be expressed as

The acoustic range signal travelling time is determined by the SSP along the ray. With SSP at the surface transducer position, we can figure out SSP along the ray. The horizontal gradient of SSF is very small and therefore the sound speed along the ray can be approximated by that along the Line of Sight (LOS). Then, let and are the azimuth angle and zenith angle of the ray observed at the seafloor transponder position x, at arbitrary depth u, we have

For approximating the ray travelling time function where L is the ray trajectory, with the Taylor series approximation we have

where

are the acoustic delays along LOS. To counterbalance the ray incident angle involved in (41), introducing the azimuthal auqengle z and then we can rewrite the model (40) into the form as follow

where is the observed value of round-trip time, is the random error of observation.

is the zenithal mapping function,

where such that can represent the zenith delay unrelated to the time-varying of LOS. The above proposed model is different from the GARPOS model which adopts a default multiplicative compensation on the RSSP as

where is a time-varying factor to characterize SSP variation, is the travel time calculated by the RSSP, is the travel time calculated by the time-varying SSP. To deal with the multiplicative compensation, we can follow the GARPOS approach taking logarithms on both sides of the observation , that is

Assuming , we can have

where is the observation error vector, is the correction coefficient, which can be parameterized by a B-spline about the time. Further considering the horizontal gradient of sound speed, GARPOS finally adopts

where is horizontal coordinate under the NEU coordinate system centered on specific original point which is the mean coordinates of transducer positions during the whole surveying session. is horizontal coordinate under the NEU coordinate system centered on specific original point which is the mean coordinates of seafloor transponder array positions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, S., Li, B., Xiao, Z. et al. Centimeter-level-precision seafloor geodetic positioning model with self-structured empirical sound speed profile. Satell Navig 4, 30 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43020-023-00120-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43020-023-00120-7