Abstract 抽象

Sustainable food production that meets consumer demands while reducing environmental impact is a critical societal challenge. The seafood industry is a key segment for the future protein supply, yet it presents environmental impacts to consider. The present study demonstrated that Irish Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas) farming has relatively low environmental impacts (i.e., 373.86 kg CO2 eq. tonne−1; 1.33 kg SO2 eq. tonne−1; and 0.39 kg PO4 eq. tonne−1) compared to other seafood and terrestrial animal sectors. Using ecosystem services metrics, one tonne of harvested oysters can remove, on average, 3.05 kg of nitrogen, 0.35 kg of phosphorus and sequester 70.52 kg of carbon from the environment, thus potentially acting as a nutrient remediator and a short-term carbon sink. These findings show how oysters can be a sustainable food source with local environmental benefits. The study also points to future work to improve the modelling of ecosystem services for bivalve production.

在满足消费者需求的同时减少对环境影响的可持续食品生产是一项重大的社会挑战。海鲜行业是未来蛋白质供应的关键部分,但它也带来了需要考虑的环境影响。本研究表明,与其他海产品和陆生动物部门相比,爱尔兰太平洋牡蛎(Magallana gigas)养殖对环境的影响相对较低(即 373.86 公斤二氧化碳当量吨 -1、1.33 千克 SO2 当量吨 -1 和 0.39 公斤 PO4 当量吨 -1)。使用生态系统服务指标,一吨收获的牡蛎平均可以去除 3.05 公斤氮、0.35 公斤磷,并从环境中封存 70.52 公斤碳,从而有可能充当营养修复剂和短期碳汇。这些发现表明牡蛎如何成为具有当地环境效益的可持续食物来源。该研究还指出了未来改进双壳类生产生态系统服务建模的工作。

Similar content being viewed by others

其他人正在查看的类似内容

Introduction 介绍

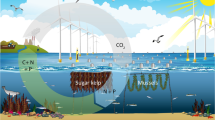

Agriculture, including terrestrial livestock, has long been the principal protein source for many societies. While food production is an essential human activity, it does have significant environmental costs, including land degradation, climate change impacts, water consumption, deforestation, non-renewable fertilisers (inc. phosphorous), eutrophication, and chemotherapeutics. These challenges have driven innovation to change food consumption habits and produce food using more sustainable systems1. The level of nutrient emissions to surface and coastal waters has increased dramatically over the past 50 years, impairing the quality of coastal waters due to eutrophication and nuisance algal blooms2,3,4. As a result, reducing nutrient loads such as nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P), and carbon (C) from anthropogenic activities (e.g., agriculture, wastewater treatment plants and industry emissions) is urgently required to address the overall deterioration of water bodies. In the context of climate change, there is also increasing urgency to reduce carbon emissions and promote carbon sequestration practices.

长期以来,包括陆生牲畜在内的农业一直是许多社会的主要蛋白质来源。虽然粮食生产是一项重要的人类活动,但它确实带来了巨大的环境成本,包括土地退化、气候变化影响、用水、森林砍伐、不可再生肥料(包括磷)、富营养化和化疗。这些挑战推动了创新,以改变食品消费习惯,并使用更可持续的系统生产食品 1。在过去 50 年中,地表和沿海水域的营养物质排放水平急剧增加,由于富营养化和令人讨厌的藻华,损害了沿海水域的质量 2,3,4。因此,迫切需要减少人为活动(例如农业、废水处理厂和工业排放)产生的氮 (N)、磷 (P) 和碳 (C) 等营养负荷,以解决水体的整体恶化问题。在气候变化的背景下,减少碳排放和推广碳封存实践的紧迫性也日益增加。

Aquaculture is the activity of farming aquatic species such as finfish, crustaceans and bivalves. It has potential as a sustainable way to produce animal protein5 and is one of the food systems with a lower environmental burden supported by recent European policy, i.e., the European Green Deal6 and the Farm to Fork Strategy7. Within the aquaculture sector, farming low trophic level species, such as bivalves, could be a more sustainable approach due to its lower environmental impact compared to current food production systems, such as terrestrial animal production8.

水产养殖是养殖有鳍鱼类、甲壳类动物和双壳类等水生物种的活动。它有潜力作为生产动物蛋白的可持续方式 5,并且是最近欧洲政策(即欧洲绿色协议 6 和从农场到餐桌战略 7)支持的环境负担较低的食品系统之一。在水产养殖部门,养殖双壳类等低营养级物种可能是一种更可持续的方法,因为与当前的粮食生产系统(例如陆生动物生产)相比,双壳类动物对环境的影响较小 8。

From a farming perspective, bivalves have lower technical and labour requirements than other aquatic species, e.g., fish and crustaceans9. Bivalve farming doesn’t require feed inputs, as this group of animals are non-feeding organisms, i.e., they take up food particles from the water column or sediment (e.g., particulate organic matter, phytoplankton and zooplankton). In terms of protein content, it can be estimated that for every tonne of oyster, 109.8 kg of protein (wet weight) is produced, considering the % of protein in dry weight10,11,12. When put in the Irish oyster farming context, ~1220.7 tonnes of protein is produced per annum (calculated by 109.8 kg protein tonne oyster−1 × 11,121 tonnes oyster year−1)13. Following the same procedure, the annual protein production from Irish blue mussels and scallops can also be estimated14,15. Compared to Pacific oysters, the national protein production from blue mussels (4708.8 tonnes of protein year−1) is relatively higher. Meanwhile, in the case of scallops, 451 tonnes of protein year−1, are produced.

从养殖的角度来看,双壳类动物的技术和劳动力要求低于其他水生物种,例如鱼类和甲壳类动物 9。双壳类养殖不需要饲料投入,因为这组动物是非摄食生物,即它们从水柱或沉积物中吸收食物颗粒(例如颗粒有机物、浮游植物和浮游动物)。就蛋白质含量而言,考虑到干重中蛋白质的百分比 109.8,可以估计每吨牡蛎可生产 10,11,12 公斤蛋白质(湿重)。当放在爱尔兰牡蛎养殖的背景下,每年生产 ~1220.7 吨蛋白质(以 109.8 公斤蛋白质吨牡蛎 -1 × 11,121 吨牡蛎年 -1)计算)13。按照相同的程序,爱尔兰蓝贻贝和扇贝的年蛋白质产量也可以估计为 14,15。与太平洋牡蛎相比,蓝贻贝的全国蛋白质产量(4708.8 吨蛋白质年 -1)相对较高。同时,扇贝年产量为 451 吨蛋白质 year-1。

In addition to being a productive protein source, bivalves can provide wider ecosystem services (ES) to the aquatic environment, such as nutrient remediation and C sequestration16,17. For instance, bivalves contribute to carbon sequestration through the shell formation process (i.e., biomineralisation), making them a potential carbon sink in the short to medium term. Several studies conducted on different shellfish species (e.g., blue mussel, Pacific oyster, clams, etc.) have highlighted the potential environmental benefits and the low impacts of bivalve farming (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 provide an extensive summary of existing literature). For instance, a Danish mussel farm estimated a potential nutrient removal of 0.6-0.9 tonne N ha−1 year−1 and 0.03-0.04 tonne P ha−1 year−1 18. A life cycle assessment (LCA) conducted in Italy showed that Manila clam (Venerupis philippinarum) and Mediterranean mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) production resulted in relatively low greenhouse gas emissions of 0.022 and 0.055 kg CO2-eq. kg harvested and packaged bivalves −1, respectively. This study also showed that clams and mussels can sequester 254 and 146 g of CO2 per kg of harvested and packaged bivalves, respectively19. Regarding Pacific oysters, in a previous study, it was estimated that Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas) aquaculture could remove 0.02−0.14 tonnes N ha−1 year−1 from seawater20. Another study estimated that farmed produced eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) releases a total of 0.13 kg CO2-eq. kg protein−1, which compared to other food sectors, was estimated to be less than 0.5% of the greenhouse gas emissions from beef, small ruminants, pork, and poultry21.

除了作为生产性蛋白质来源外,双壳类动物还可以为水生环境提供更广泛的生态系统服务 (ES),例如养分修复和碳封存 16,17。例如,双壳类动物通过壳形成过程(即生物矿化)促进碳封存,使其成为中短期内潜在的碳汇。对不同贝类(例如蓝贻贝、太平洋牡蛎、蛤蜊等)进行的几项研究强调了双壳类养殖的潜在环境效益和低影响(补充表 1 和 2 提供了对现有文献的广泛总结)。例如,丹麦的一个贻贝养殖场估计潜在的养分去除量为 0.6-0.9 吨 N ha-1 年 -1 和 0.03-0.04 吨 P ha-1 年 -1 18。在意大利进行的生命周期评估 (LCA) 表明,马尼拉蛤 (Venerupis philippinarum) 和地中海贻贝 (Mytilus galloprovincialis) 生产导致的温室气体排放量相对较低,分别为 0.022 和 0.055 kg CO2-eq. kg 收获和包装双壳类 -1。这项研究还表明,蛤蜊和贻贝每公斤收获和包装的双壳类动物可分别封存 254 克和 146 克二氧化碳 19。关于太平洋牡蛎,在之前的一项研究中,估计太平洋牡蛎(Magallana gigas)水产养殖可以从海水中去除 0.02−0.14 吨 N ha−1 年 −1 20。另一项研究估计,养殖生产的东部牡蛎 (Crassostrea virginica) 总共释放 0.13 公斤 CO2-eq。 与其他食品部门相比,公斤蛋白质 −1 估计不到牛肉、小型反刍动物、猪肉和家禽温室气体排放量的 0.5%21。

Combining ecosystem services (i.e., nutrient remediation and carbon sequestration) with the environmental impacts of bivalve farming (i.e., eutrophication potential and global warming potential) is still an emerging area of research. Considerable gaps remain in our understanding of biochemical processes and wider environmental interactions. Much of the published data have been generated in the United States, where some species are not currently farmed in the EU22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Overall, limited research has been undertaken within the EU9,18,20,29,30,31, with variability in the methodologies used, making it challenging to extract broad conclusions. In addition, most of the studies combining LCA and ES for shellfish only covered the net carbon capture potential of shellfish farming19,32,33.

将生态系统服务(即养分修复和碳封存)与双壳类养殖的环境影响(即富营养化潜力和全球变暖潜力)相结合仍然是一个新兴的研究领域。我们在对生化过程和更广泛的环境相互作用的理解方面仍然存在相当大的差距。大部分已发表的数据都是在美国产生的,欧盟目前没有养殖一些物种 22,23,24,25,26,27,28。总体而言,欧盟 9,18,20,29,30,31 范围内进行的研究有限,所使用的方法存在差异,因此很难得出广泛的结论。此外,大多数结合贝类 LCA 和 ES 的研究仅涵盖贝类养殖的净碳捕获潜力 19,32,33。

Despite the wider potential benefits of bivalve aquaculture, European production of farmed mussels and oysters has been in decline. Previous studies have pointed out disease prevalence, lack of mussel and oyster seed, and low profitability as the main causes of the decline of the sector in the European Union and the EU34,35. To ensure the sustainable expansion of bivalve aquaculture, the current performance of the bivalve sector, in relation to nutrient and carbon emissions, requires further research to enable benchmark data and comparison to other sectors.

尽管双壳类水产养殖具有更广泛的潜在好处,但欧洲养殖贻贝和牡蛎的产量一直在下降。此前的研究指出,疾病流行、缺乏贻贝和牡蛎种子以及盈利能力低下是欧盟和欧盟该行业下滑的主要原因 34,35。为确保双壳类水产养殖的可持续扩张,双壳类行业目前在营养和碳排放方面的表现需要进一步研究,以提供基准数据并与其他部门进行比较。

To better appraise the environmental performance, sustainability credentials and benefits of the Irish oyster-producing sector, this study evaluated the ES and environmental impacts of Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas) farming by

为了更好地评估爱尔兰牡蛎生产部门的环境绩效、可持续性证书和效益,本研究通过以下方式评估了太平洋牡蛎 (Magallana gigas) 养殖的 ES 和环境影响

-

1.

Assessing the nutrient remediation (i.e., N and P) and C sequestration potential ES of Pacific Oyster through morphological and elemental analysis of representative samples;

通过对代表性样品的形态学和元素分析,评估太平洋牡蛎的养分修复(即氮和磷)和碳封存潜力 ES; -

2.

Analysing the environmental impacts of oyster aquaculture by undertaking LCAs of regional Pacific oyster farms; and

通过对太平洋区域牡蛎养殖场进行生命周期评估,分析牡蛎养殖对环境的影响;和 -

3.

Combining ES and LCAs results to determine the benefits of Pacific oyster culture in terms of eutrophication (i.e., N and P net remediation) and global warming potential (i.e., net C sink).

结合 ES 和 LCA 结果来确定太平洋牡蛎养殖在富营养化(即氮和磷净修复)和全球变暖潜能值(即净碳汇)方面的益处。

The study combined ES and LCA approaches to provide a more holistic evaluation of the ecological potential of bivalve aquaculture and the environmental impact of their production.

该研究结合了 ES 和 LCA 方法,对双壳类水产养殖的生态潜力及其生产对环境的影响进行了更全面的评估。

Results 结果

Ecosystem services 生态系统服务

The morphological analysis results of the three size classes of Pacific oyster at each production site studied are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Results of the nutrient (i.e., %N and %P) and carbon content (i.e., %C) analysis for each site and size investigated did not show significant differences in %N and %C values between sites and sizes (Supplementary Table 4). %P values followed a similar trend as %C and %N, with homogeneous values between sites and sizes. Results to farm scale were extrapolated in terms of a fresh whole product to compare them across the entire Irish sector for Pacific oyster farming. Since no significant differences in nutrient and carbon % were observed between size categories for a given site (Supplementary Table 4), nutrient and carbon content values were averaged per site to express the kg of N, P and C removed from the sea per tonne of fresh product per site (Fig. 1). The results showed increased removal of nutrients (77.3% more N removed per tonne) and carbon (13.4% more C removed per tonne) in Site 2 compared to Site 1 (Fig. 1a, c). In terms of P removed, Site 2 removed 50% more P per tonne of fresh product than Site 1 (Fig. 1b).

每个研究生产地点的三种大小类别的太平洋牡蛎的形态分析结果见附表 3。所研究的每个地点和大小的养分(即 %N 和 %P)和碳含量(即 %C)分析结果显示,不同地点和大小之间的 %N 和 %C 值没有显着差异(补充表 4)。%P 值遵循与 %C 和 %N 类似的趋势,位点和大小之间的值是均匀的。根据新鲜的整个产品对养殖规模的结果进行推断,以比较整个爱尔兰太平洋牡蛎养殖部门的结果。由于给定地点的大小类别之间没有观察到营养物质和碳百分比的显着差异(补充表 4),因此对每个地点的营养物质和碳含量值进行平均,以表示每个地点每吨新鲜产品从海洋中去除的氮、磷和碳的公斤数(图 1999999 年)。 结果显示,与 1 号站点相比,2 号站点的养分去除量增加 77.3%(每吨去除的氮增加 13.4%)和碳(每吨去除的碳增加 13.4%)增加[图 1a,c]。就去除的磷而言,站点 2 每吨新鲜产品去除的磷比站点 1 多 50%(图 1)。1b)。

图1:研究地点生产的每吨太平洋牡蛎从海洋中去除的营养物质和碳。

a Nitrogen removed per tonne of fresh Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas) product harvested per site investigated. Values are mean ± standard deviation, n = 3. b Phosphorous removed per tonne of fresh Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas) product harvested per site investigated. Values are mean ± standard deviation, n = 3. c Carbon removed per tonne of fresh Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas) product harvested per site investigated. Values are mean ± standard deviation, n = 3.

a 每个调查地点每收获一吨新鲜太平洋牡蛎 (Magallana gigas) 产品去除的氮。值为标准差±平均值,n = 3。b 每个调查地点每收获一吨新鲜太平洋牡蛎(Magallana gigas)产品去除磷。值为标准差±平均值,n = 3。c 每个调查地点每收获一吨新鲜太平洋牡蛎(Magallana gigas)产品所去除的碳。值为标准差±平均值,n = 3。

Extrapolating the oyster data at the national scale (i.e., Irish production), the results showed that 834.3 tonnes of C, 33.9 tonnes of N and 3.9 tonnes of P could potentially be removed from the Irish coastal waters per annum (Table 1). From the economic perspective, this would be equivalent to a nutrient removal value of €1.9 million year−1, of which N removal accounts for the most significant proportion (i.e., 97.67%). In terms of population equivalent, the amounts of N removed annually from the investigated sites are comparable to the N emitted by populations of 51 (Site 1) and 230 (Site 2). Based on the national extrapolation, the Irish Pacific oyster sector could potentially remove the nitrogen content equivalent to the wastewater generated by 10,285 people.

推断全国尺度的牡蛎数据(即爱尔兰产量),结果表明,每年可能从爱尔兰沿海水域去除 834.3 吨 C、33.9 吨 N 和 3.9 吨 P(表 1)。从经济角度来看,这相当于每年−1 的养分去除值为 190 万欧元,其中氮去除量占最大比例(即 97.67%)。就种群当量而言,每年从调查地点去除的氮量与 51 个种群(地点 1)和 230 个种群(地点 2)排放的氮量相当。根据国家推断,爱尔兰太平洋牡蛎部门可能会去除相当于 10,285 人产生的废水的氮含量。

表1 根据年均产量和估计养分去除值推断每个地点每年去除的碳、氮和磷量的结果

Life cycle assessment 生命周期评估

The LCA results for 1 tonne of Pacific oysters produced in 2019 (Supplementary Table 7; Fig. 2a) showed an estimated GWP of 373.86 kg CO2 eq. The single most significant contributor to GWP was grading and packing at 38%. This was driven by the use of electricity to operate the various grading machines, hoppers and shaking tables for processing and grading the oysters. The second largest contributor to GWP was diesel production and combustion at 20% of GWP. Electricity data was provided as an annual figure for the whole farming site but was not measured for individual equipment. Therefore, it was not possible to differentiate between activities such as grading, processing, or stock deployment. Trestles accounted for 17% of GWP, followed by depuration at 16% of GWP. The remaining inputs (i.e., bags and seed production) contributed 10% to GWP.

2019 年生产的 1 吨太平洋牡蛎的生命周期评估结果(补充表 7;无花果。2a)的估计 GWP 为 373.86 kg CO2 eq。全球升温潜能值最重要的贡献者是分级和包装,占 38%。这是由使用电力来作各种分级机、料斗和振动台来处理和分级牡蛎所推动的。全球升温潜能值的第二大贡献者是柴油生产和燃烧,占全球升温潜能值的 20%。电力数据以整个农场的年度数据形式提供,但未针对单个设备进行测量。因此,无法区分分级、加工或库存部署等活动。栈桥占 GWP 的 17%,其次是净化,占 GWP 的 16%。其余投入(即袋子和种子生产)对全球升温潜能值的贡献率为 10%。

图2:2019年生产的1吨太平洋牡蛎的生命周期评估结果。

a The contribution of the environmental burden from the farming processes to produce a tonne of fresh Pacific oysters (Magallana gigas) to market. b Impact assessment of the Cumulative Energy Demand for a tonne of fresh Pacific oysters.

a 养殖过程对生产一吨新鲜太平洋牡蛎(Magallana gigas)推向市场的环境负担的贡献。b 对一吨新鲜太平洋牡蛎的累计能源需求的影响评估。

The AP for 1 tonne of oysters were estimated to be 1.33 kg SO2 eq. Diesel combustion and production accounted for 41% of the AP. The steel that was used in the production of the trestles contributed to 18% of AP. The remaining contributors were those relying on the use of energy. Grading, packing, and depuration combined accounted for 31% of AP. The remaining 10% of AP arose from oyster bag production (6%) and seed production (4%). The EP for a tonne of oysters was estimated to be 0.4 kg PO4 eq. Trestle production accounted for 33% of the EP. The combustion of diesel was the second largest contributor at 27%, followed by depuration at 13%. CED was 4,757.5 MJ tonne−1 of oysters. The contribution of each process followed a similar pattern to the other impact categories, except for diesel production, which accounted for 22% of energy demand. In contrast with other impact categories, the contribution from oyster bag production was higher, accounting for 16% of CED. When assessed across the different energy categories, the primary energy source for oyster production comes from non-renewable fossil fuels (Fig. 2b).

1 吨牡蛎的 AP 估计为 1.33 公斤 SO2 eq。柴油燃烧和生产占 AP 的 41%。用于生产栈桥的钢材占 AP 的 18%。其余的贡献者是那些依赖能源使用的人。分级、包装和净化合计占 AP 的 31%。其余 10% 的 AP 来自牡蛎袋生产 (6%) 和种子生产 (4%)。一吨牡蛎的 EP 估计为 0.4 kg PO4 eq。栈桥产量占 EP 的 33%。柴油燃烧是第二大贡献者,占 27%,其次是净化,占 13%。CED 为 4,757.5 MJ 吨 -1 牡蛎。每个过程的贡献与其他影响类别相似,但柴油生产占能源需求的 22% 除外。与其他影响类别相比,牡蛎袋生产的贡献更高,占 CED 的 16%。在对不同能源类别进行评估时,牡蛎生产的主要能源来自不可再生的化石燃料(图 1999 年)。2b)。

Life cycle assessment and ecosystem services

生命周期评估和生态系统服务

The quantification of oyster ES (i.e., nutrient remediation and carbon sequestration) resulted in improved EP and GWP emissions. When characterised to PO4 eq., oyster shells were able to sequester 2.36 kg PO4 eq. tonne−1 (combining N and P values) and 1.28 kg PO4 eq. tonne−1 (only N values) (Fig. 3a). When compared to the EP of oyster production at this site (0.39 kg PO4 eq. tonne−1, Supplementary Table 7), the results indicate that Pacific oyster production has a high nutrient remediation potential. Considering only the N remediation potential, Pacific oysters sequestered 228.2% more kg PO4 eq. tonne−1 than emitted, resulting in a negative eutrophication potential (i.e., −0.89 kg PO4 eq. tonne−1). When C was characterised as CO2 eq., results show that 273.54 kg CO2 eq. tonne−1 was bound in the shell (Fig. 3b). When compared to the estimated GWP for Pacific oyster production to farmgate (373.86 kg CO2 eq. tonne−1, Supplementary Table 7), carbon emissions from Pacific oyster farming are reduced by 73.17%, resulting in a balanced emission of 100.32 kg CO2 eq. tonne−1.

牡蛎 ES 的量化(即养分修复和固碳)改善了 EP 和 GWP 排放。当以 PO4 当量表征时,牡蛎壳能够封存 2.36 kg PO4 当量吨 -1(结合 N 和 P 值)和 1.28 kg PO4 当量吨 -1(仅 N 值)(图。3a). 与该地点牡蛎生产的 EP(0.39 kg PO4 等吨 -1,补充表 7)相比,结果表明太平洋牡蛎生产具有很高的养分修复潜力。仅考虑氮修复潜力,太平洋牡蛎的封存量 kg PO 4 当量吨 -1 比排放量多 228.2%,导致负富营养化潜力(即 -0.89 kg PO4 当量吨 -1)。当 C 被表征为 CO2 eq.时,结果表明,273.54 kg CO2 eq. tonne−1 结合在壳中(图 13b). 与太平洋牡蛎生产到养殖场的全球升温潜能值估计值(373.86 kg CO2 当量吨-1,补充表 7)相比,太平洋牡蛎养殖的碳排放量减少了 73.17%,从而平衡排放了 100.32 kg CO2 当量吨-1。

图3:太平洋牡蛎生态系统服务量化。

a kg of PO4 eq. sequestered (i.e., nutrient remediation), emitted (i.e., Life Cycle Assessment emissions from oyster farming) and balanced [i.e., Kg of PO4 eq. emitted (LCA)- Kg of PO4 eq. sequestered (N)] per tonne of Pacific oyster harvested. b kg CO2 eq. sequestered (i.e., carbon sequestration), emitted (i.e., Life Cycle Assessment emissions from oyster farming) and balanced [i.e., Kg of CO2 eq. emitted (LCA)- Kg of CO2 eq. sequestered] per tonne of Pacific oyster harvested. N nitrogen, P phosphorous, LCA life cycle assessment.

每吨收获的太平洋牡蛎封存(即养分修复)、排放(即牡蛎养殖的生命周期评估排放量)和平衡[即每吨太平洋牡蛎排放的 PO4 当量 (LCA)-封存的 PO4 当量 (N) 公斤)。b kgCO2 当量封存(即碳封存)、排放量(即牡蛎养殖的生命周期评估排放量)和平衡 [即二氧化碳排放量 (LCA)-封存的 CO2 当量公斤] 每吨太平洋牡蛎。 氮氮、磷、LCA 生命周期评估。

Discussion 讨论

The present study appraised Ireland’s Pacific oyster production system, its contribution to ES, and its environmental impact through LCA. The designed experimental protocol produced data on the nutrients and C sequestration potential of one of the most farmed shellfish species in the country and globally36. The results obtained in the present study showed similar %C, %N, and %P in Pacific oyster shells and tissues compared to other shellfish species17. In terms of C sequestration and nutrient removal ES, the current Irish oyster sector may have a C sequestration potential of 834.3 tonnes year−1 and N and P removal potential of 33.9 and 3.9 tonnes year−1, respectively. Comparison with other ES studies in shellfish species is difficult due to differences in the metrics used. Compared to the present results for Pacific oyster farming (i.e., 3.05 kg N tonne oyster−1, 0.35 kg P tonne oyster−1 and 70.52 kg C tonne oyster−1), a study conducted on blue mussels showed higher nutrient removal and carbon sequestration potential (i.e., 5.0–8.5 kg N tonne mussel−1, 0.43–0.95 kg P tonne mussel−1 and 74.7-77.5 kg C tonne mussel−1)37. Due to resource limitations, only nutrient removal and C sequestration processes associated with oyster farming were investigated in this study. Hence, the net nutrient removal and C sequestration potential of oyster farming could change if nutrient and C emissions from shellfish were assessed within the experimental boundaries. The accumulation of faeces and pseudo-faeces under the oyster trestles results in bio-deposition, a process where seabed sediments are enriched with organic matter, N and P bio-deposits. Studies on the effects of oyster reefs on microbial diversity and ecosystem processes38,39 reported increased CO2 fluxes in habitats covered by Pacific oysters, possibly related to increased microbial activity from the decomposition of organic matter supplied in oyster biodeposits. Therefore, enriched sediments could be used as a potential energy and food source for invertebrate consumers, thus stimulating primary productivity and creating geological modifications of the underlying sediment40. On the other hand, several studies41,42 have pointed out that the calcification process of bivalve shells releases CO2 into the environment, thus altering the CO2 fluxes of oyster cultivation. However43,44, discussed that because shell production can be considered a by-product of the main ecosystem value of bivalve aquaculture, partitioning of the CO2 respired between the soft tissue and shell could be justified when including bivalve shells in the carbon trading system. In addition, a recent study introduced a new potential negative emission technology concept, namely, Carbon Sequestration via bivalve Shellfish Farming (CSSF) from the ecosystem perspective, with a net carbon sequestration ratio of 13.64% for oysters when compared to a natural ecosystem (i.e., ~1%)45.

本研究评估了爱尔兰的太平洋牡蛎生产系统、其对 ES 的贡献以及通过 LCA 对环境的影响。设计的实验方案产生了有关该国乃至全球养殖最多的贝类物种之一的营养物质和碳封存潜力的数据 36。本研究获得的结果表明,与其他贝类物种相比,太平洋牡蛎壳和组织中的%C、%N 和%P 相似 17。在碳封存和养分去除 ES 方面,目前爱尔兰牡蛎部门的碳封存潜力可能为 834.3 吨年 -1,氮和磷去除潜力分别为 33.9 吨和 3.9 吨。 由于所用指标的差异,很难与其他贝类 ES 研究进行比较。与目前太平洋牡蛎养殖的结果(即 3.05 kg N 吨牡蛎 −1、0.35 kg P 吨牡蛎 −1 和 70.52 kg C 吨牡蛎 −1)相比,一项针对蓝贻贝的研究表明,蓝贻贝具有更高的养分去除和固碳潜力(即 5.0–8.5 kg N 吨贻贝 −1、0.43–0.95 kg P 吨贻贝 −1 和 74.7-77.5 kg C 吨贻贝 −1)37.由于资源限制,本研究仅研究了与牡蛎养殖相关的养分去除和碳封存过程。因此,如果在实验范围内评估贝类的养分和碳排放量,牡蛎养殖的净养分去除和碳封存潜力可能会发生变化。粪便和假粪便在牡蛎栈桥下的积累导致生物沉积,即海底沉积物富含有机质、氮和磷生物沉积物的过程。 关于牡蛎礁对微生物多样性和生态系统过程影响的研究 38,39 报告说,太平洋牡蛎覆盖的栖息地的 CO2 通量增加,这可能与牡蛎生物沉积物中供应的有机物分解导致微生物活动增加有关。因此,富集沉积物可以作为无脊椎动物消费者的潜在能量和食物来源,从而刺激初级生产力并对底层沉积物产生地质变化 40。另一方面,多项研究 41,42 指出,双壳类贝壳的钙化过程将 CO2 释放到环境中,从而改变牡蛎养殖的 CO2 通量。然而,43,44 讨论了由于贝壳生产可以被认为是双壳类水产养殖主要生态系统价值的副产品,因此当将双壳类贝壳纳入碳交易系统时,软组织和贝壳之间呼吸的 CO2 的分配是合理的。此外,最近的一项研究引入了一种新的潜在负排放技术概念,即从生态系统角度出发,即通过双壳类贝类养殖(CSSF)进行碳封存,与自然生态系统相比,牡蛎的净碳封存率为 13.64%(即~1%)45。

Regarding the nitrogen flux, bivalves can also contribute to N removal through denitrification mechanisms. Denitrification is the microbial conversion of reactive N to inert nitrogen gas (N2). Oyster production can stimulate denitrification in three ways: (1) by enhancing denitrification through increased deposition of organic matter in sediments; (2) through denitrifying bacteria present in their bodies; and/or (3) by providing habitat for other filter-feeding macrofaunal communities46. A meta-analysis on oysters’ impact on coastal biogeochemistry compared the effect of an oyster ecosystems on N fluxes and denitrification potential using data from 45 studies. The meta-analysis highlighted the potential for denitrification as an N removal mechanism in oyster habitats and aquaculture sites47. Despite the positive evidence of denitrification effects from oyster habitats, its consideration as a nutrient remediation process must be done cautiously, as it may vary according to the site characteristics, species studied, water quality, benthic habitat, nutrient fluxes and the methodology used to measure denitrification47,48. Therefore, in order to include shellfish aquaculture in carbon trading schemes and footprint calculations, a deeper understanding of the regional impact and interaction of oysters to the nutrient and carbon fluxes is needed. This would include the frequent analysis of the nutrients and carbon removal in the water column and the oysters, as well as a mass balance approach under laboratory conditions to gauge the impact and interactive effects.

关于氮通量,双壳类动物也可以通过反硝化机制促进氮的去除。反硝化是微生物将反应性氮转化为惰性氮气 (N2)。牡蛎生产可以通过三种方式刺激反硝化:(1)通过增加沉积物中有机物的沉积来增强反硝化;(2)通过体内存在的反硝化细菌;和/或 (3) 为其他滤食性大型动物群落提供栖息地 46.一项关于牡蛎对沿海生物地球化学影响的荟萃分析使用来自 45 项研究的数据比较了牡蛎生态系统对氮通量和反硝化潜力的影响。荟萃分析强调了反硝化作为牡蛎栖息地和水产养殖场氮去除机制的潜力 47。尽管有积极证据表明牡蛎栖息地具有反硝化作用,但必须谨慎考虑将其作为养分修复过程,因为它可能会根据地点特征、研究的物种、水质、底栖栖息地、养分通量和用于测量反硝化的方法而有所不同 47,48.因此,为了将贝类水产养殖纳入碳交易计划和足迹计算,需要更深入地了解牡蛎对营养物质和碳通量的区域影响和相互作用。这包括经常分析水柱和牡蛎中的营养物质和碳去除量,以及在实验室条件下采用质量平衡方法来衡量影响和相互作用。

Due to limited data, several assumptions were made for the extrapolation of results. To extrapolate the shellfish individual results to farm level, it was assumed that shellfish from across the farm uptake carbon and nutrients the same way as the average performance obtained from the sampled individuals. This assumption is justified since the most affecting parameters (i.e., shellfish species, cultivating condition and water quality) on nutrients and C sequestration potential were considered constant at the farm level49,50. In the national extrapolation, it was assumed that shellfish from all farming sites across Ireland would perform at the same level as the ones investigated. The farms investigated in this study were located on the west coast of Ireland, where water quality, environmental conditions, and cultivation practices differ from those on the southern and eastern Irish coasts. Therefore, future research should investigate other shellfish-producing areas to confirm the present results and expand the number of oyster samples assessed to increase the resolution of N, P, and C bioaccumulation datasets.

由于数据有限,对结果的推断做出了一些假设。为了将贝类个体结果外推到农场层面,假设整个农场的贝类吸收碳和养分的方式与从采样个体获得的平均性能相同。这一假设是合理的,因为对养分和碳封存潜力影响最大的参数(即贝类物种、养殖条件和水质)在养殖场层面被认为是恒定的 49,50。在全国推断中,假设来自爱尔兰所有养殖场的贝类将与所调查的贝类处于相同的水平。本研究调查的农场位于爱尔兰西海岸,那里的水质、环境条件和种植方式与爱尔兰南部和东部海岸不同。因此,未来的研究应该调查其他贝类产区以证实目前的结果,并扩大评估的牡蛎样本数量,以提高 N、P 和 C 生物累积数据集的分辨率。

In terms of value, in 2022, the Irish oyster farming industry recorded an income of ~ €64.45 million, with production costs of ~ €41.19 million13. Although oyster farming is the second largest industry in the Irish aquaculture sector, several constraints exist to promote its growth. It has been shown that farmers experience a lack of capital for investment, mainly related to the problems of Ireland’s licensing system. Market expansion is limited by these licensing problems, as they can hinder the implementation of innovative farming techniques to make the industry more efficient and sustainable51. Therefore, if a nutrient credit programme were implemented at the national and international level, nutrient removal from oyster production would represent a potential benefit of €1.9 million annually to the Irish shellfish sector. This benefit could be used to reduce production costs, as capital for investment, and to support marketing efforts to expand the sector and make it more profitable.

就价值而言,2022 年,爱尔兰牡蛎养殖业的收入为 ~ 6445 万欧元,生产成本为 ~ 4119 万欧元 13.尽管牡蛎养殖是爱尔兰水产养殖业的第二大产业,但促进其增长存在一些限制。研究表明,农民缺乏投资资本,这主要与爱尔兰的许可制度问题有关。市场扩张受到这些许可问题的限制,因为它们可能会阻碍创新农业技术的实施,从而使该行业更加高效和可持续 51。因此,如果在国家和国际层面实施营养信贷计划,从牡蛎生产中去除营养物质将每年为爱尔兰贝类部门带来 190 万欧元的潜在利益。这一好处可用于降低生产成本,作为投资资本,并支持营销工作以扩大该行业并使其更有利可图。

Due to the lack of European-derived data sets, the monetary benefit of the present study was estimated based on the nutrient removal valuation methodology of a previous U.S. based study29. Therefore, to accurately reflect the current European and Irish oyster farming status, more studies are needed on the valuation of ecosystem services in Europe. It is now recognised that bivalve production provides not only ecosystem services but also cultural and economic services. The high amounts of C, N and P in oyster shells give them great potential for use in various applications. A study conducted in Korea found that oyster shell meal used as a liming agent for agricultural fields significantly increased soil pH and improved soil nutritional status, i.e., available phosphate and organic matter mass52. Shellfish shells could also be used as calcium supplements for livestock. The addition of venus shells (Venus gallina) to a limestone supplement significantly improved the egg production performance of laying hens53. Oyster shells could also be a sustainable alternative to traditional building materials (e.g., mortar sand). A study conducted in South Korea showed that small oyster shell particles (2-0.074 mm) were a potential substitute for conventional mortar sands in terms of compressive strength54. Additionally, waste oyster shells are a potential hard substrate for preparing artificial reefs for coral and oyster reef restoration55,56,57,58. Hence, the reuse of oyster shells and their variety of applications could represent a new income stream for the oyster industry, while allowing its transition towards a blue circular economy.

由于缺乏源自欧洲的数据集,本研究的金钱效益是根据之前美国研究的养分去除评估方法估算的 29。因此,为了准确反映欧洲和爱尔兰的牡蛎养殖现状,需要对欧洲生态系统服务的估值进行更多的研究。现在人们认识到,双壳类生产不仅提供生态系统服务,还提供文化和经济服务。牡蛎壳中大量的 C、N 和 P 使其具有用于各种应用的巨大潜力。在韩国进行的一项研究发现,用作农田石灰剂的牡蛎壳粉可显着提高土壤 pH 值并改善土壤营养状况,即有效磷酸盐和有机质质量 52。贝壳也可用作牲畜的钙补充剂。在石灰石补充剂中添加金星壳(Venus gallina)显着提高了蛋鸡的产蛋性能 53.牡蛎壳也可以成为传统建筑材料(例如砂浆砂)的可持续替代品。在韩国进行的一项研究表明,就抗压强度而言,小牡蛎壳颗粒(2-0.074 毫米)是传统砂浆砂的潜在替代品 54。此外,废牡蛎壳是为珊瑚和牡蛎礁恢复准备人工鱼礁的潜在硬基质 55,56,57,58。因此,牡蛎壳的再利用及其各种应用可以为牡蛎产业带来新的收入来源,同时使其向蓝色循环经济过渡。

In the Irish Pacific oyster farming sector, fuel use (i.e., use of tractors for oyster harvesting) and energy use (i.e., grading and packaging) were the main drivers of the environmental burden. Infrastructure and equipment played a secondary role in environmental impact. The low service life of the oyster bags and trestles influenced all impact categories. Recent LCA studies on shellfish aquaculture have also reported similar findings, with 39% of GWP for mussels farmed in Italy arising from equipment and infrastructure19. To reduce the operation-associated impacts, operators could apply alternative approaches to lower fuel and energy use, such as using renewable energy sources (e.g., biofuels and green hydrogen) or investing in more efficient engines. According to the Renewable Energy Directive, by 2030, EU countries must ensure that the share of renewables in final energy consumption in transport is at least 14%, including a minimum share of 3.5% of advanced biofuels59. On the other hand, extending the service life of the farming equipment could reduce infrastructure-associated impacts in oyster farming.

在爱尔兰太平洋牡蛎养殖部门,燃料使用(即使用拖拉机捕捞牡蛎)和能源使用(即分级和包装)是环境负担的主要驱动因素。基础设施和设备在环境影响中发挥了次要作用。蚝袋和栈桥的低使用寿命影响了所有冲击类别。最近关于贝类水产养殖的生命周期评估研究也报告了类似的发现,意大利养殖的贻贝 39% 的 GWP 来自设备和基础设施 19。为了减少与运营相关的影响,运营商可以采用替代方法来降低燃料和能源使用,例如使用可再生能源(例如生物燃料和绿色氢气)或投资更高效的发动机。根据《可再生能源指令》,到 2030 年,欧盟国家必须确保可再生能源在交通运输最终能源消耗中的份额至少为 14%,其中先进生物燃料的份额至少为 3.5%59。另一方面,延长养殖设备的使用寿命可以减少牡蛎养殖中与基础设施相关的影响。

In food LCAs, there have been increasing calls for studies to present the results as a function of the system60,61. For food production systems, that is its contribution to human nutrition and food security and thus the results of this study were also considered in terms of protein production, their relative impacts, and ecosystem services. To produce 1 kg of protein from oyster production, there is a need for 28.9 kg of shelled oysters (based on an edible yield of 32% and a protein content of 10.8%). This would result in GWP of 10.8 kg CO2 eq./kg of oyster protein, AP of 0.04 kg SO2 eq., 0.01 kg PO4 eq., and CED of 137.7 MJ. The resultant shell material from 28.9 kg of oysters would result in 19.68 kg of oyster shell, which would have bound 5.11 kg CO2 eq. Subtracting this sequestered CO2 from the emitted CO2 would result in 5.71 kg CO2 eq./kg of oyster protein. This would also result in an edible protein energy return (ep-EROI) on investment of 8.2% (based on the assumption that 1 kg of protein is equal to 16.73 MJ) which is within the ranges of previously published values62.

在食品生命周期评估中,越来越多的人呼吁研究将结果呈现为系统的函数 60,61。对于粮食生产系统来说,这是它对人类营养和粮食安全的贡献,因此本研究的结果也从蛋白质生产、其相对影响和生态系统服务的角度考虑。要从牡蛎生产中生产 1 公斤蛋白质,需要 28.9 公斤带壳牡蛎(基于 32% 的食用产量和 10.8% 的蛋白质含量)。这将导致 GWP 为 10.8 kg CO2 当量/kg 牡蛎蛋白,AP 为 0.04 kg SO2 当量,0.01 kg PO4 当量,CED 为 137.7 MJ。由 28.9 公斤牡蛎产生的壳材料将产生 19.68 公斤牡蛎壳,这将结合 5.11 公斤 CO2 eq。从排放的 CO2 中减去这种封存的 CO2 将得到 5.71 kg CO2 当量/kg 牡蛎蛋白。这也将导致投资的食用蛋白质能量回报 (ep-EROI) 为 8.2%(基于 1 公斤蛋白质等于 16.73 MJ 的假设),这在先前公布的值 62 的范围内。

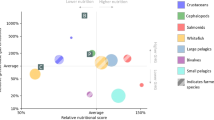

Overall, oyster farming has shown relatively low global impacts on the environment compared to other seafood production sectors (e.g., wild catch fisheries and aquaculture) or livestock farming (Supplementary Table 2). However, within LCAs, it is difficult to compare the results of one study with those of another confidently due to differences in scope, system boundaries, data availability, assumptions, and methodology. The main environmental drivers in producing animal proteins from aquaculture, fisheries, and terrestrial farming are feed production, energy use, and fuel use. Furthermore, these food production systems are more complex in their life cycle stages, requiring sophisticated infrastructure, more labour, complex technologies (e.g., recirculating aquaculture systems, flow-through aquaculture systems), and additional processing steps (e.g., feed production, slaughtering, meat processing). In contrast, oyster farming has a less complex lifecycle than other farmed animal species and is typically undertaken using traditional techniques (i.e., non-fed rack-and-bag culture on intertidal areas) that do not require feed input and sophisticated infrastructures. There may be opportunities in the bivalve sector for value-added or novel food products targeted at environmentally conscious consumers. These strategic prospects may exist in high-growth food sectors, such as sports nutrition and snacks, for marketing it as a proteinous and nutritious food. Additional opportunities exist in pairing bivalves’ nutritional density and environmental performance to inform consumers better how they can meet their nutritional requirements while limiting their environmental impact63. While the present study demonstrates a low ecological impact, future LCAs should aim to increase the sample size of farms to obtain more solid results. In addition, there is a need to expand the scope of the study higher up the value chain and look at value-added products and the valorisation of circular economy opportunities for bivalve waste and shells in particular.

总体而言,与其他海产品生产部门(例如野生渔获渔业和水产养殖)或畜牧业相比,牡蛎养殖业对全球环境的影响相对较小(补充表 2)。然而,在 LCA 中,由于范围、系统边界、数据可用性、假设和方法的差异,很难自信地将一项研究的结果与另一项研究的结果进行比较。通过水产养殖、渔业和陆地养殖生产动物蛋白的主要环境驱动因素是饲料生产、能源使用和燃料使用。此外,这些粮食生产系统在其生命周期阶段更加复杂,需要复杂的基础设施、更多的劳动力、复杂的技术(例如循环水产养殖系统、流通式水产养殖系统)和额外的加工步骤(例如饲料生产、屠宰、肉类加工)。相比之下,牡蛎养殖的生命周期不如其他养殖动物物种复杂,并且通常使用不需要饲料输入和复杂基础设施的传统技术(即潮间带的非饲料桶袋养殖)进行。双壳类行业可能有机会针对具有环保意识的消费者提供增值或新型食品。这些战略前景可能存在于高增长的食品领域,例如运动营养品和零食,将其作为蛋白质和营养食品进行营销。将双壳类动物的营养密度和环境绩效相结合还存在更多机会,以更好地告知消费者如何满足其营养需求,同时限制其对环境的影响 63。 虽然本研究显示对生态的影响很小,但未来的生命周期评估应旨在增加农场的样本量,以获得更可靠的结果。此外,有必要将研究范围扩大到价值链的上游,并着眼于增值产品,特别是双壳类废物和贝壳的循环经济机会的价值化。

Given the potential of oyster farming in nutrient uptake, there are opportunities to use or include oyster aquaculture in integrated catchment management. With many Irish rivers failing to meet the requirements of the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC)64 and the national herd increasing, the pairing or co-location of these food production systems as complementary activities can mitigate the excess of nutrients in coastal and transitional waters, while producing a low carbon food product. This integrated approach may be limited regarding suitable sites, but novel and emerging oyster culture systems may address this.

鉴于牡蛎养殖在养分吸收方面的潜力,有机会使用牡蛎水产养殖或将牡蛎养殖纳入集水区综合管理。由于许多爱尔兰河流未能满足《水框架指令》(2000/60/EC)64 的要求,并且全国河流数量不断增加,将这些粮食生产系统作为补充活动进行配对或共置,可以减轻沿海和过渡水域营养物质的过剩,同时生产低碳食品。这种综合方法在合适的地点可能受到限制,但新兴的牡蛎养殖系统可以解决这个问题。

In addition, uncertainty exists regarding the balanced EP results presented in this study.

此外,本研究中提出的平衡 EP 结果存在不确定性。

Determining the balanced EP of oyster farming by combining EP-emitted values by LCA approaches with the results of nutrient extraction is challenging. To date, the researchers of the present study are not aware of an approved methodology for estimating the net EP from bivalve production systems. Consequently, the authors used a first-principles approach similar to the estimation of net GWP, where the GHG contribution is considered as CO2 equivalents to an atmospheric pool, whereas EP does not necessarily consider a common pool estimate. In addition, the life cycle impact assessment methodology used was the CML method65. This is one of the oldest LCIA methodologies, but it is still one of the most widely used in fisheries and aquaculture LCAs66,67. The methodology is limited as it does not include fate and exposure, time horizon and geographical scale65. Furthermore, it presents EP as a worst-case scenario, assuming that 100% of emissions contribute to impacts68. On the other hand, results may also vary if more recent EP characterisation factors are used to convert N and P content in shells to PO4 eq. As can be seen, there is a distinct gap in the tools available to model the nutrient removal potential of bivalves under an LCA framework. However, there have been recent advances in the field of understanding the biogeochemical processes of shellfish denitrification and their potential in nutrient management and removal46,47,48,69. Therefore, considering these limitations, future work should focus on developing an LCA methodology that can accurately model and include the nutrient remediation processes more completely as part of LCAs to estimate the net EP of bivalve production systems.

通过将 LCA 方法的 EP 排放值与养分提取结果相结合,确定牡蛎养殖的平衡 EP 具有挑战性。迄今为止,本研究的研究人员还不知道估计双壳类生产系统净 EP 的批准方法。因此,作者使用了类似于净全球升温潜能值估计的第一性原理方法,其中温室气体贡献被视为相当于大气池的二氧化碳 , 而 EP 不一定考虑共同池估计。此外,使用的生命周期影响评估方法是 CML 方法 65。这是最古老的 LCIA 方法之一,但它仍然是渔业和水产养殖 LCA 中使用最广泛的方法之一 66,67。该方法有限,因为它不包括命运和暴露、时间范围和地理尺度 65。此外,它还将 EP 作为最坏情况,假设 100% 的排放量会导致影响 68。另一方面,如果使用较新的 EP 表征因子将壳中的氮和磷含量转换为 PO4 当量,则结果也可能有所不同。可以看出,在 LCA 框架下,可用于模拟双壳类动物营养去除潜力的工具存在明显差距。然而,在了解贝类反硝化的生物地球化学过程及其在养分管理和去除方面的潜力方面,近年来取得了进展 46,47,48,69。 因此,考虑到这些局限性,未来的工作应侧重于开发一种 LCA 方法,该方法可以准确地建模并更完整地将养分修复过程作为 LCA 的一部分,以估计双壳类生产系统的净 EP。

The present study also shows the carbon sequestration potential of oyster production (274 kg CO2 eq. tonne harvested oysters−1), which is higher compared to clams (254 kg CO2 eq. tonne harvested clams−1) and mussel (146 kg CO2 eq. tonne harvested mussels−1) farming19. With carbon farming being included in the EU’s new Common Agriculture Policy Strategic Plan 2023-2027, there is also an opportunity for bivalve aquaculture to aid and play an active role in this form of environmental management70. Although acidification potential was calculated for the LCA process, this impact category wasn’t considered in the ecosystem services due to the resource limitation of this study. However, if included, the sulfur cycle should also be considered in the calculations, as oysters may promote hydrogen sulfide production in anaerobic conditions that can occur beneath the oyster trestles71.

本研究还显示了牡蛎生产(274 kg CO2 当量吨收获牡蛎-1)的固碳潜力,与蛤蜊(254 kg CO2 当量吨收获的蛤蜊 -1)和贻贝(146 kg CO2 当量吨收获的贻贝 -1)养殖相比更高 19。随着碳农业被纳入欧盟新的《2023-2027 年共同农业政策战略计划》,双壳类水产养殖也有机会在这种形式的环境管理中提供帮助并发挥积极作用 70。尽管计算了 LCA 过程的酸化潜力,但由于本研究的资源限制,生态系统服务中并未考虑这一影响类别。然而,如果包括硫循环,则在计算中还应考虑硫循环,因为牡蛎可能会在牡蛎栈桥下方可能发生的厌氧条件下促进硫化氢的产生 71。

Ecosystem influences such as changes to the benthos community, introduction of invasive species, pests and diseases, creation of novel habitats from the farming structures, alteration of nutrient cycling, effect on higher trophic level animals, etc, should be considered under sustainability assessments. The scope of this study didn’t allow for measurement of these ecosystem influences; however, previous research has highlighted their importance and consideration to improve the sustainability of oyster aquaculture72,73,74. In addition, point-of-harvest impacts such as mechanical stress (i.e., benthos compaction by workers and tractor pathway) could also affect the benthos macrofauna in oyster farming sites74. Another study conducted in a salmon hatchery also showed the importance of supplementing (where relevant) life cycle assessments with broader ecosystem assessments75. Therefore, to have a comprehensive understanding of the environmental impacts and benefits of oyster farming, future research should measure ecosystem and points-of harvest impacts, ideally with comparison to a similar virgin site over a suitable time frame.

可持续性评估应考虑生态系统的影响,例如底栖生物群落的变化、入侵物种、病虫害的引入、从农业结构中创造新的栖息地、养分循环的改变、对高营养级动物的影响等。这项研究的范围不允许测量这些生态系统的影响;然而,先前的研究强调了它们对于提高牡蛎水产养殖可持续性的重要性和考虑 72,73,74。此外,收获点的影响,如机械应力(即工人的底栖压实和拖拉机路径)也可能影响牡蛎养殖场的底栖大型动物群 74。在鲑鱼孵化场进行的另一项研究也表明,用更广泛的生态系统评估来补充(在相关情况下)生命周期评估的重要性 75。因此,为了全面了解牡蛎养殖对环境的影响和效益,未来的研究应该测量生态系统和收获点的影响,最好是在合适的时间范围内与类似的处女地进行比较。

The seafood sector, including aquaculture producers, processors, wholesalers, retailers and food certification bodies, is facing a growing demand for information on the environmental footprint of their products from customers, investors and government agencies76. The present study provides a scientific basis to meet these informational demands and contribute to the imminent introduction of a science-based metric such as the Product Environmental Footprint77. This study brings an innovative and valuable approach with positive results, thus serving as a reference point for future research on the sustainable potential of the shellfish sector.

包括水产养殖生产商、加工商、批发商、零售商和食品认证机构在内的海产品部门正面临着客户、投资者和政府机构对其产品环境足迹信息的需求日益增长 76。本研究为满足这些信息需求提供了科学依据,并有助于即将引入基于科学的指标,例如产品环境足迹 77。这项研究带来了一种创新且有价值的方法,并取得了积极成果,从而为未来研究贝类部门的可持续潜力提供了参考点。

Methods 方法

Site selection 选址

The oyster production sites (i.e., oyster producers or buyers for further processing) used in this study were located on a sheltered bay northwest of the Republic of Ireland. Samples from two Pacific oyster-producing sites (i.e., Site 1 and Site 2) were collected for morphological and elemental analysis, while the LCAs were modelled using operational data from three Pacific oyster farms located along the West coast, i.e., Site 1, Site 3 and Site 4, (Fig. 4).

本研究中使用的牡蛎生产基地(即牡蛎生产商或进一步加工的买家)位于爱尔兰共和国西北部的一个避风海湾。收集了来自两个太平洋牡蛎生产地(即站点 1 和站点 2)的样本进行形态学和元素分析,同时使用位于西海岸的三个太平洋牡蛎养殖场(即站点 1、站点 3 和站点 4)的运营数据对 LCA 进行建模(图 1)。4)。

图4:生命周期评估和生态系统模型数据收集的研究概述。

Solid boxes represent procedures. Dashed boxes represent outcomes. L large size, M medium size, S small size, N nitrogen, P phosphorus, C carbon, LCA life cycle assessment, GWP global warming potential, EP eutrophication potential, AP acidification potential, CED cumulative energy demand. Created in BioRender. Wan, A. (2024) BioRender.com/a57b755

实心框表示程序。虚线框表示结果。L 大尺寸、M 中尺寸、S 小尺寸、N 氮、磷、碳碳、LCA 生命周期评估、GWP 全球变暖潜能值、EP 富营养化潜能值、AP 酸化潜能值、CED 累计能源需求。在 BioRender 中创建。万 A. (2024) BioRender.com/a57b755

Ecosystem services methodology

生态系统服务方法

Morphological and elemental analyis

形态学和元素分析

For morphological and elemental analysis, farmers at each production site randomly harvested 15 individuals per market size category (i.e., small, 67.4–112.5 mm length; medium, 89.4–119.3 mm length; and large, 94.8–120.7 mm length) during different times of the winter season (i.e., February and March). Thus, there were a total of 45 samples per site. The following morphometric measurements were undertaken per oyster:

为了进行形态学和元素分析,每个生产地点的农民在冬季的不同时间(即 2 月和 3 月)随机收获每个市场规模类别(即小型,长度 67.4-112.5 毫米;中型,长度 89.4-119.3 毫米;大型,长度 94.8-120.7 毫米)15 只。因此,每个站点共有 45 个样本。对每只牡蛎进行了以下形态测量 :

-

a. 一个。

Total shell length, width, and depth; mm oyster−1;

壳的总长度、宽度和深度;毫米牡蛎 −1; -

b.

Total wet weight; g oyster−1;

总湿重;g 牡蛎 −1; -

c.

Shell wet weight and tissue wet weight; g oyster−1,

壳湿重和组织湿重;g 牡蛎 −1, -

d.

Dry tissue and shell weights; g oyster−1.

干纸巾和贝壳重量;g 牡蛎 −1。

Among the 15 individuals morphologically assessed per site and size category, sets of 6 individuals were randomly selected and pooled for the elemental analysis37. Thus, for each site, 18 individuals were selected for elemental analysis. Tissue and shells from pooled individuals were dried in a fan-assisted oven at 80 °C until a constant weight was achieved. Dried tissue and shells from pooled individuals were crushed using a mortar and pestle for dried tissue and a mill for dried shells. The pooled tissue and shell samples were then analysed for N and C content through an elemental CHN analyser (Flash smart elemental analyser, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States). P content was measured through Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (700 series ICP-OES, Agilent, Santa Clara, California, United States). The results obtained as %C, %N, and %P in the dried tissue and shell samples were used to calculate: (i) the average %C, %N and %P per individual oyster (and separately the tissue and shell for each oyster), size category and site investigated; (ii) the average mass of C, N, and P removed per fresh individual oyster; and (iii) the average mass of C, N, and P removed per tonne of oysters harvested. Differences in the elemental analysis (i.e., %C, %N, %P) of Pacific oyster between the three size classes and the sites investigated were analysed using two-way ANOVA tests. A post-hoc Tukey’s test was conducted on each dataset to discern significant differences between sizes and sites. Statistical significance was assigned when P < 0.05.

在按部位和大小类别进行形态学评估的 15 个个体中,随机选择 6 个个体并汇总进行元素分析 37。因此,对于每个地点,选择 18 个个体进行元素分析。将来自混合个体的组织和贝壳在 80 °C 的风扇辅助烘箱中干燥,直到达到恒定重量。使用研钵和杵将来自混合个体的干燥组织和贝壳压碎,用于干燥组织,并使用磨机将干燥的贝壳压碎。然后通过元素 CHN 分析仪(Flash 智能元素分析仪,Thermo Fisher,Waltham,Massachusetts,United States)分析混合的组织和贝壳样品的 N 和 C 含量。通过电感耦合等离子体发射光谱法(700 系列 ICP-OES,安捷伦,圣克拉拉,加利福尼亚州,美国)测量 P 含量。使用干燥组织和壳样品中获得的%C、%N 和%P 结果来计算:(i)每个牡蛎的平均%C、%N 和%P(以及每个牡蛎的组织和壳)、大小类别和地点;(ii)每只新鲜牡蛎去除的 C、N 和 P 的平均质量;(iii) 每吨牡蛎去除的 C、N 和 P 的平均质量。使用双向方差分析检验分析了三个大小等级和研究地点之间太平洋牡蛎元素分析(即%C、%N、%P)的差异。对每个数据集进行了事后 Tukey 检验,以辨别大小和站点之间的显着差异。当 P < 0.05 时分配统计学意义。

National ecological impact

国家生态影响

The morphological and elemental analysis results were then extrapolated to farm and national scale to obtain: (a) the quantities of nutrients and carbon removed annually on each production site using the average annual production for the period 2015–2020, i.e., average annual production (tonne year−1) × N, P or C removed per tonne of fresh product (kg tonne−1); and (b) national extrapolation of nutrients and carbon removed using the most recent estimated total annual production of Irish Pacific oysters13, i.e., N, P or C removed per tonne of fresh product (kg tonne−1) × national production of Pacific oysters (tonne year−1).

然后将形态和元素分析结果外推到农场和国家规模,得到:(a)使用 2015-2020 年期间的平均年产量,即每吨新鲜产品(公斤吨 -1)去除的氮、磷或碳×年平均年产量(吨年 −1));(b) 使用爱尔兰太平洋牡蛎 13 的最新估计年总产量(即每吨新鲜产品 (kg tonne-1) ×去除的氮、磷或碳 (N、P 或 C) 的全国外推 13 太平洋牡蛎的全国产量(吨年 -1)。

An ecosystem services analysis of Pacific oyster farming was undertaken to associate a monetary value with the nutrient remediation potential. This valuation of nutrient removal ES was calculated using the following median values for the removal of N (€18.9 kg−1) and P (€33.9 kg−1)29. These monetary values represent the theoretical cost of upgrading a wastewater treatment plant to remove one kg of N and P. Such values can vary between treatment plants depending on existing load, plant technology, discharge limits, plant size, etc. Nutrient valuation was also extrapolated nationally by applying the national production of Pacific oysters for 202213. Results were also equated to wastewater treatment plant performance in terms of population equivalent for N removal. A wastewater treatment plant, with secondary treatment, was estimated to remove, on average, 3.3 kg N person−1 year−1 25. This figure was applied to calculate the population equivalent where a wastewater treatment plant would remove the amount of N remediated (extrapolated as per the above) by Pacific oyster farming in Ireland.

对太平洋牡蛎养殖进行了生态系统服务分析,以将货币价值与养分修复潜力联系起来。养分去除量 ES 的估值是使用以下去除氮(18.9 欧元 kg−1)和磷(33.9 欧元 kg−1)29 的中值计算的。这些货币价值代表了升级污水处理厂以去除一公斤氮和磷的理论成本。这些值可能会因处理厂而异,具体取决于现有负荷、工厂技术、排放限值、工厂规模等。通过应用 2022 年太平洋牡蛎的全国产量,还在全国范围内推断了营养价值 13.结果也等同于废水处理厂的性能,以去除氮的人口当量计算。据估计,经过二级处理的废水处理厂平均可减少 3.3 公斤氮人 −1 年 −125。该数字用于计算废水处理厂去除爱尔兰太平洋牡蛎养殖修复的氮量(根据上述推断)的种群当量。

Life cycle assessment methodology

生命周期评估方法

Goal and scope 目标和范围

LCA studies were undertaken on three Pacific oyster sites along Ireland’s West coast. A cradle-to-gate system boundary was used for each site’s farming and on-site processing activities. The systems boundaries included aquaculture infrastructure, seed procurement, consumable materials, energy production (electric and diesel), culture and harvesting, processing, and packaging. Waste management and treatment of waste materials and packaging are also included within the system boundaries. The functional units applied were one tonne of live oyster product (meat and shell). Each studied site produced, on average, 111 tonnes of oysters for the market annually. All sites used bags and trestles to grow their oysters, and oyster seed was purchased domestically (Fig. 5).

LCA 研究在爱尔兰西海岸的三个太平洋牡蛎场进行了。每个地点的农业和现场加工活动都使用了从摇篮到大门的系统边界。系统边界包括水产养殖基础设施、种子采购、消耗品、能源生产(电力和柴油)、养殖和收获、加工和包装。废物管理以及废料和包装的处理也包括在系统范围内。应用的功能单位是一吨活牡蛎产品(肉和壳)。每个研究地点平均每年为市场生产 111 吨牡蛎。所有地点都使用袋子和栈桥来种植牡蛎,牡蛎种子是在国内购买的(图 1)。5)。

图5:爱尔兰西北部太平洋牡蛎生产所用养殖材料的摇篮到大门系统边界和示意图

a System boundaries used in the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Pacific oyster production in the north-west of Ireland. The solid boxes represent processes (foreground and background). The dot-dashed box indicates the system boundaries. Solid arrows depict direct mass flows, and dashed arrows indicate indirect mass flows. b Plan and longitudinal overview of the layout and dimensions of oyster trestles. c Typical trestle setup and oyster bags used on the farming sites.

a 爱尔兰西北部太平洋牡蛎生产生命周期评估中使用的系统边界。实心框表示进程(前景和背景)。点虚线框表示系统边界。实线箭头表示直接质量流量,虚线箭头表示间接质量流量。b 牡蛎栈桥布局和尺寸的平面图和纵向概览。c 养殖场地使用的典型栈桥装置和牡蛎袋。

Life cycle inventory 生命周期清单

The life cycle inventory used primary data from the partner farms. Primary data was collected through questionnaires, interviews, and site visits. Energy, fuel, and consumables values were validated against bills and invoices where possible. Secondary data was collected from established life cycle databases such as Ecoinvent v3.10, and Agribalyse 3.0.1 to populate the life cycle inventories. The life cycle inventory of the present study covers all farm-based activities, infrastructures, and use of resources (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). The main transport vehicles used for daily farming activities at each site were a fleet of tractors and trailers. The trestles at each site were manufactured from 25 mm reinforced steel bars and weighed 18 kg per segment. The service life of the trestles was estimated to be 15 years. Oyster bags were made of high-density polyethene and weighed approximately 800 g per bag, with an average service life of 8 years.

生命周期清单使用来自合作伙伴场的主要数据。主要数据是通过问卷调查、访谈和实地考察收集的。在可能的情况下,根据账单和发票验证能源、燃料和消耗品价值。从已建立的生命周期数据库(例如 Ecoinvent v3.10 和 Agribalyse 3.0.1)收集二手数据,以填充生命周期清单。本研究的生命周期清单涵盖了所有基于农场的活动、基础设施和资源使用(补充表 5 和 6)。每个地点用于日常农业活动的主要运输车辆是拖拉机和拖车车队。每个地点的栈桥均由 25 毫米钢筋制成,每段重 18 公斤。栈桥的使用寿命估计为 15 年。牡蛎袋由高密度聚乙烯制成,每袋重约 800 克,平均使用寿命为 8 年。

Life cycle assessment

The life cycle impact assessment methodology was undertaken through the CML method65. The following impact assessment categories were included: 100-year global warming potential (GWP, kg CO2 eq.), Acidification potential (AP, kg SO2 eq.), Eutrophication potential (EP, kg PO4 eq.), and Cumulative energy demand (CED, MJ), which assesses the degree of energy consumption associated with a production system78. As previously reported, these impact categories are the most concerning for aquaculture and shellfish production systems66,79,80.

Life cycle assessment and ecosystem services

In this study, the elemental analysis results (i.e., N, P, and C content in Pacific oyster shells) were adapted to LCA impact categories to estimate the eutrophication potential and global warming potential equivalents of nutrient uptake provided by Pacific oyster aquaculture in Ireland. N and P content in the shell were converted to PO4 eq., a compatible form under the EP impact category. Characterisation factors of 0.42 and 3.07 were applied to convert N and P to PO4 eq., respectively81. To determine the balanced PO4 eq. emissions, only the N content in shells converted to PO4 eq. was considered, as N is typically the limiting nutrient in the marine environments68. In addition, it should be noted that the CML methodology used for this life cycle impact assessment doesn’t distinguish between freshwater and marine eutrophication. Therefore, the balanced PO4 eq emissions were calculated as follows: balanced PO4 eq = emitted PO4 eq (LCA)—sequestered PO4 eq (N), where emitted PO4 eq (LCA) are the PO4 eq emissions from the LCA results and sequestered PO4 eq (N) are the PO4 eq. converted values from N content in oyster shells. To determine the net GWP of Pacific oyster farming, C content in oyster shells (i.e., the amount of CO2 sequestered in the shell during biocalcification) was converted to CO2 eq32. The same calculation was applied to determine the net CO2 eq emissions: balanced CO2 eq = emitted CO2 eq (LCA)—sequestered CO2 eq., where emitted CO2 eq (LCA) is the CO2 eq emissions from the LCA results and sequestered CO2 eq are the CO2 eq. converted values from C content in oyster shells. The N, C, and P contained in the soft tissue were not included within the ES calculations as they are considered a short stage of the biogenic carbon cycle. On the contrary, shells can sequester nutrients for extended periods19,21.

本研究将元素分析结果(即太平洋牡蛎壳中的氮、磷和碳含量)适应 LCA 影响类别,以估计爱尔兰太平洋牡蛎养殖提供的富营养化潜能值和全球变暖潜能值。壳中的 N 和 P 含量转化为 PO4 当量,这是 EP 冲击类别下的兼容形式。采用 0.42 和 3.07 的表征因子分别将 N 和 P 转换为 PO4 等式,81。为了确定平衡的 PO4 当量排放,仅考虑了转换为 PO4 当量的贝壳中的氮含量,因为氮通常是海洋环境中的限制性营养物质 68。此外,应该注意的是,用于该生命周期影响评估的 CML 方法没有区分淡水和海洋富营养化。因此,平衡的 PO4 当量排放量计算如下:平衡 PO4 当量=排放的 PO4 当量(LCA)—封存的 PO4 当量(N),其中排放的 PO4 当量(LCA)是 LCA 结果的 PO4 当量排放量,封存的 PO4 当量(N)是牡蛎壳中氮含量的 PO4 当量换算值。为了确定太平洋牡蛎养殖的净 GWP,将牡蛎壳中的 C 含量(即生物钙化过程中壳中封存的 CO2 量)转换为 CO2 eq32。 采用相同的计算来确定净 CO2 当量排放量:平衡的 CO2 当量 = 排放的 CO2 当量 (LCA)—封存的 CO2 当量,其中排放的 CO2 当量 (LCA) 是 LCA 结果中的 CO2 当量排放量,封存的 CO2 当量是牡蛎壳中 C 含量的 CO2 当量换算值。软组织中所含的 N、C 和 P 不包括在 ES 计算中,因为它们被认为是生物碳循环的短阶段。相反,贝壳可以长时间封存营养物质 19,21。

Data availability 数据可用性

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access data storage at University of Galway.

由于敏感性的原因,支持本研究结果的数据无法公开提供,可根据合理要求从通讯作者处获得。数据位于戈尔韦大学的受控访问数据存储中。

References 引用

Ilea, R. C. Intensive livestock farming: Global trends, increased environmental concerns, and ethical solutions. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 22, 153–167 (2009).

Ilea, RC 集约化畜牧业:全球趋势、日益严重的环境问题和道德解决方案。J. 农业环境。伦理学 22, 153–167 (2009)。Maúre, E. D. R., Terauchi, G., Ishizaka, J., Clinton, N. & DeWitt, M. Globally consistent assessment of coastal eutrophication. Nat. Commun. 12, 6142 (2021).

Maúre, E. D. R., Terauchi, G., Ishizaka, J., Clinton, N. & DeWitt, M. 沿海富营养化的全球一致评估。 国家公社。12, 6142 (2021)。EPA, Environmental Protection Agency. Water Quality in 2020: An indicators Report. Prepared by W. Trodd and S. O’Boyle. ISBN: 978-1-84095-965-9 (2020). https://www.epa.ie/pubs/reports/water/waterqua/Water%20Quality%20in%202019%20-%20an%20indicators%20report.pdf (Accessed 15 November 2023).

EPA,环境保护署。2020 年水质:指标报告 。 由 W. 特罗德和 S. 奥博伊 e. ISBN:978-1-84095-965-9 (2020)。https://www.epa.ie/pubs/reports/water/waterqua/Water%20Quality%20in%202019%20-%20an%20indicators%20report.pdf(2023 年 11 月 15 日访问)。Wan, A. H. et al. Assessment and characterisation of Ireland’s green tides (Ulva species). PLoS ONE 12 (2017).

Wan, AH 等人。爱尔兰绿潮(石莼物种)的评估和表征。 公共科学图书馆一号 12 (2017)。Jiang, Q., Bhattarai, N., Pahlow, M. & Xu, Z. Environmental sustainability and footprints of global aquaculture. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 180, 106183 (2022).

江 Q.、巴塔莱 N.、帕洛 M. 和徐 Z. 全球水产养殖的环境可持续性和足迹。 资源。保护。回收。180, 106183 (2022)。European Commission. The European Green Deal. COM (2019) 640 final (2019). https://www.eea.europa.eu/policy-documents/com-2019-640-final (Accessed 15 November 2023).

欧盟委员会。 欧洲绿色协议。COM (2019) 640 决赛 (2019)。https://www.eea.europa.eu/policy-documents/com-2019-640-final(2023 年 11 月 15 日访问)。European Commission. Farm to fork strategy. DG SANTE/Unit ‘Food information and composition, Food Waste’(DG SANTE/Unit ‘Food Inf. Compos. food waste’):23 (2020). https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en (Accessed 15 November 2023).

欧盟委员会。 从农场到餐桌的策略 。DG SANTE/ 单位“食品信息和组成,食物浪费”(DG SANTE/单位“食物信息成分”):23 (2020)。https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en(2023 年 11 月 15 日访问)。Krause, G. et al. Prospects of low trophic marine aquaculture contributing to food security in a net zero-carbon world. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6 https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.875509 (2022)

克劳斯,G. 等人。低营养海洋养殖在净零碳世界中促进粮食安全的前景。 前面。维持。食品系统 6https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.875509 (2022)Nielsen, P., Cranford, P. J., Maar, M. & Petersen, J. K. Magnitude, spatial scale and optimisation of ecosystem services from a nutrient extraction mussel farm in the eutrophic Skive Fjord, Denmark. Aquacult Environ. Interact. 8, 311–329 (2016).

Nielsen, P.、Cranford, PJ、Maar, M. 和 Petersen, JK 丹麦富营养化斯基夫峡湾营养提取贻贝养殖场的规模、空间尺度和生态系统服务优化。 水族养殖环境。互动。8, 311–329 (2016)。Zhu, Y., Qi Li, H. Y. & Lingfeng, K. Biochemical composition and nutritional value of different shell color strains of Pacific oyster Crassostrea Gigas. J. Ocean Univ. China 17, 897–904 (2018).

Zhu, Y., Qi Li, H. Y. & Lingfeng, K. 太平洋牡蛎 Crassostrea Gigas 不同壳色菌株的生化成分和营养价值。 海洋大学学报 17, 897–904 (2018).Linehan, L. G., O’Connor, T. P. & Burnell, G. Seasonal variation in the chemical composition and fatty acid profile of Pacific oysters (Crassostrea Gigas). Food Chem. 64, 211–214 (1999).

Linehan, L. G., O'Connor, TP 和 Burnell, G. 太平洋牡蛎 (Crassostrea Gigas) 化学成分和脂肪酸谱的季节性变化。 食品化学。64, 211–214 (1999)。Minhaz, T. M. et al. Data on growth performance, proximate composition, and fatty acid content of edible oyster (Crassostrea Spp.), farmed on shellstring along Cox’s Bazar Coast. Data Brief. 33, 106450 (2020).

Minhaz, TM 等人。关于科克斯巴扎尔海岸贝带养殖的食用牡蛎 (Crassostrea Spp.) 的生长性能、近似成分和脂肪酸含量的数据。 数据简介。33, 106450 (2020)。Dennis, J., Jackson, E., Perry, S., Burmanje, J. & Rihan, D. BIM Annual Aquaculture Report. https://afloat.ie/port-news/fishing/bim/item/61036-bim-publishes-its-annual-aquaculture-report-for-2022 (2023).

Dennis, J.、Jackson, E.、Perry, S.、Burmanje, J. 和 Rihan, D. BIM 年度水产养殖报告 。https://afloat.ie/port-news/fishing/bim/item/61036-bim-publishes-its-annual-aquaculture-report-for-2022 (2023)。Venugopal, V. & Gopakumar, K. Shellfish: nutritive value, health benefits, and consumer safety. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 16, 1219–1242 (2017).

Venugopal, V. 和 Gopakumar, K. 贝类:营养价值、健康益处和消费者安全。Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf.16, 1219–1242 (2017)。BIM. THE BUSINESS OF SEAFOOD. A snapshot of Ireland’s seafood sector (2022). https://bim.ie/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/BIM-The-Business-of-Seafood-2022.pdf.

比姆。海鲜业务。爱尔兰海鲜行业概况(2022 年)。https://bim.ie/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/BIM-The-Business-of-Seafood-2022.pdf。Higgins, C. B., Stephenson, K. & Brown, B. L. Nutrient bioassimilation capacity of aquacultured oysters: quantification of an ecosystem service. J. Environ. Qual. 40, 271–277 (2011).

Higgins, C. B., Stephenson, K. &; Brown, B. L. 水产养殖牡蛎的营养生物同化能力:生态系统服务的量化。J. 环境。质量。40, 271–277 (2011)。Van der Schatte Olivier, A. et al. A global review of the ecosystem services provided by bivalve aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 12, 3–25 (2020).

范德夏特·奥利维尔,A. 等人。双壳类水产养殖提供的生态系统服务的全球审查。 阿夸克牧师。12, 3–25 (2020)。Petersen, J. K. et al. Mussels as a tool for mitigation of nutrients in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 82, 137–143 (2014).

Tamburini, E., Turolla, E., Lanzoni, M., Moore, D. & Castaldelli, G. Manila clam and Mediterranean mussel aquaculture is sustainable and a net carbon sink. Sci. Tot. Environ. 848, 157508 (2022).

Rose, J. M., Bricker, S. B. & Ferreira, J. G. Comparative analysis of modelled nitrogen removal by shellfish farms. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 91, 185–190 (2015).

Ray, N. E., Maguire, T. J., Al-Haj, A. N., Henning, M. C. & Fulweiler, R. W. Low greenhouse gas emissions from oyster aquaculture. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 9118–9127 (2019).

Bricker, S. B. et al. Bioextractive removal of nitrogen by oysters in Great Bay Piscataqua River Estuary, New Hampshire, USA. Estuaries Coasts 43, 23–38 (2020).

Dvarskas, A. et al. Quantification and valuation of nitrogen removal services provided by commercial shellfish aquaculture at the sub watershed scale. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 16156–16165 (2020).

Parker, M. & Bricker, S. Sustainable oyster aquaculture, water quality improvement, and ecosystem service value potential in Maryland Chesapeake Bay. J. Shellfish Res. 39, 269–281 (2020).

Bricker, S. B. et al. Role of shellfish aquaculture in the reduction of eutrophication in an urban Estuary. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 173–183 (2018).

Galimany, E. et al. Cultivation of the ribbed mussel (Geukensia demissa) for nutrient bioextraction in an urban estuary. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 13311–13318 (2017).

Grizzle, R. E. et al. Growth, morphometrics, and nutrient content of farmed eastern oysters, Crassostrea virginica (Gmelin), in New Hampshire, USA. Aquac. Res. 48, 1525–1537 (2017).

Reitsma, J., Murphy, D. C., Archer, A. F. & York, R. H. Nitrogen extraction potential of wild and cultured bivalves harvested from nearshore waters of Cape Cod, USA. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 116, 175–181 (2017).

Carss, D. N. et al. Ecosystem services provided by a non-cultured shellfish species: The common cockle Cerastoderma edule. Mar. Environ. Res. 158, 104931 (2020).

Petersen, J. K., Saurel, C., Nielsen, P. & Timmermall, K. The use of shellfish for eutrophication control. Aquac. Int 24, 857–878 (2015).

Ferreira, J. G. et al. Analysis of coastal and offshore aquaculture: Application of the FARM model to multiple systems and shellfish species. Aquaculture 289, 32–41 (2009).

Martini, A. et al. Environmental performance and shell formation-related carbon flows for mussel farming systems. Sci. Total Environ. 831, 154891 (2022).

Turolla, E., Castaldelli, G., Fano, E. A. & Tamburini, E. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) proves that Manila clam farming (Ruditapes philippinarum) is a fully sustainable aquaculture practice and a carbon sink. Sustainability 12, 5252 (2020).

Botta, R., Asche, F., Borsum, S. J. & Camp, E. V. A review of global oyster aquaculture production and consumption. Mar. Policy 117, 103952 (2020).

Avdelas, L. et al. The decline of mussel aquaculture in the European union: causes, economic impacts and opportunities. Rev. Aquac. 13, 91–118 (2021).

FAO. Magallana gigas. Cultured aquatic species information programme. Text by Helm, M. M. Fisheries and Aquaculture Division [online]. Rome. Updated 2006-06-08 (2023). https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/culturedspecies/crassostrea_gigas (Accessed 08 December 2023).

van der Schatte Olivier, A. et al. Geographical variation in the carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus content of blue mussels, Mytilus edulis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 167, 112291 (2021).

Green, D. S., Boots, B. & Crowe, T. P. Effects of non-indigenous oysters on microbial diversity and ecosystem functioning. PLoS ONE 7, 1–10 (2012).

Green, D. S., Rocha, C. & Crowe, T. P. Effects of non-indigenous oysters on ecosystem processes vary with abundance and context. Ecosystems 16, 881–893 (2013).

Ahmed, OO. & Solomon, OO. Ecological consequences of oysters culture. J. Fish Lives Product. 04 https://doi.org/10.4172/2332-2608.1000198 (2016).

Morris, J. P. & Humphreys, M. P. Modelling seawater carbonate chemistry in shellfish aquaculture regions: Insights into CO2 release associated with shell formation and growth. Aquaculture 501, 338–344 (2019).

Ray, N. E., O’Meara, T., Wiliamson, T., Izursa, J. L. & Kangas, P. C. Consideration of carbon dioxide release during shell production in LCA of bivalves. Int J. Life Cycle Assess. 23, 1042–1048 (2018).

Filgueira, R. et al. An integrated ecosystem approach for assessing the potential role of cultivated bivalve shells as part of the carbon trading system. Mar. Eco Prog. Ser. 518, 281–287 (2015).

Filgueira, R., Strohmeier, T. & Strand, Ø. in Goods and Services of Marine Bivalves (eds Smaal, A. et al.) (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96776-9_12.

Feng, J. C., Sun, L. & Yan, J.Carbon sequestration via shellfish farming: A potential negative emissions technology. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.113018 (2023).

Ayvazian, S. et al. Beyond bioextraction: the role of oyster-mediated denitrification in nutrient management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 14457–14465 (2021).

Ray, N. E. & Fulweiler, R. W. Meta-analysis of oyster impacts on coastal biogeochemistry. Nat. Sustain. 4, 261–269 (2021).

Ray, N. E. et al. A review of how we assess denitrification in oyster habitats and proposed guidelines for future studies. LO Methods 19, 714–731 (2021).

Buer, A.-L., Taylor, D., Bergström, P., Ritzenhofen, L. & Klemmstein, A. Nitrogen and phosphorous content in blue mussels (Mytilus spp.) across the Baltic Sea. Front Mar. Sci. 7, 705 (2020).

Holbach, A., Maar, M., Timmermann, K. & Taylor, D. A spatial model for nutrient mitigation potential of blue mussel farms in the western Baltic Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 736, 139624 (2020).

Renwick, A. Regulatory challenges to economic growth in aquaculture: The case of licensing in the Irish oyster industry. Mar. Policy 88, 151–157 (2018).

Lee, C., Lee, D., Ali, M. A. & Kim, P. J. Effects of oyster shell on soil chemical and biological properties and cabbage productivity as a liming material. Waste Manag. 28, 2702–2708 (2008).

Cath, A. et al. Performance and egg quality of aged laying hens fed diets supplemented with meat and bone meal or oyster shell meal. S Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 42, 74–82 (2012).

Yoon, H., Park, S., Lee, K. & Park, J. Oyster shell as substitute for aggregate in mortar. Waste Manag. Res. 22, 158–170 (2004).

Kong, J. et al. Recycling of waste oyster shell and recycled aggregate in the porous ecological concrete used for artificial reefs. Constr. Build Mater. 323, 126447 (2022).

Levine, E., Gosnell, J., Goetz, E. & Malinowski, C. Natural clutch type influences habitat preference and predation, but not survival, in reef-associated species. Restor. Ecol. 25, 101–111 (2017).

Waldbusser, G., Steenson, R. & Green, M. Oyster shell dissolution rates in estuarine waters: effects of pH and shell legacy. J. Shellfish Res. 30, 659–669 (2011).

Mann, R. & Powell, E. N. Why oyster restoration goals in the Chesapeake Bay are not and probably cannot be achieved. J. Shellfish Res. 26, 905–917 (2007).

European Commission, Biofuels (2023). Available from https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/renewable-energy/bioenergy/biofuels_en#documents (Accessed 14 March 2024).

Fernández-Ríos, A. et al. Towards a water-energy-food (WEF) nexus index: a review of nutrient profile models as a fundamental pillar of food and nutrition security. Sci. Total Environ. 789, 147936 (2021).

McAuliffe, G. A., Takahashi, T. & Lee, M. R. F. Applications of nutritional functional units in commodity-level life cycle assessment (LCA) of agri-food systems. Int J. Life Cycle Assess. 25, 208–221 (2020).

Vázquez-Rowe, I., Villanueva-Rey, P., Moreira, M. T. & Feijoo, G. Edible protein energy return on investment ratio (ep-EROI) for Spanish seafood products. AMBIO 43, 381–394 (2014).

Hallström, E. et al. Combined climate and nutritional performance of seafoods. J. Clean. Prod. 230, 402–411 (2019).

European Commission. DIRECTIVE 2000/60/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 23 October 2000 Establishing a framework for community action in the field of water policy, 327 1–73 (2000). Available from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32000L0060 (Accessed on 15/11/2023).

Guinée, J. B. Handbook on life cycle assessment: operational guide to the ISO standards. Int J. LCA 7, 311–313 (2002).

Bohnes, F. A. & Laurent, A. LCA of aquaculture systems: methodological issues and potential improvements. Int J. LCA 24, 324–337 (2019).

Ruiz-Salmón, I. et al. Life cycle assessment of fish and seafood processed products—a review of methodologies and new challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 761, 144094 (2021).

Payen, S., Cosme, N. & Elliott, A. H. Freshwater eutrophication: spatially explicit fate factors for nitrogen and phosphorus emissions at the global scale. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 26, 388–401 (2021).

Humphries, A. T. et al. Directly measured denitrification reveals oyster aquaculture and restored oyster reefs remove nitrogen at comparable high rates. Front. Mar Sci, 3 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2016.00074 (2016).

European Commission. Approved 28 CAP Strategic Plans (2023-2027) Facts and figures (2023). Available from https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/cap-my-country/cap-strategic-plans_en (Accessed 15 November 2023).

Yamamoto, T., Kim, K. H. & Shirono, K. A pilot study on remediation of sediments enriched by oyster farming wastes using granulated coal ash. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 90, 54–59 (2015).

Forrest, B. M., Keeley, N. B., Hopkins, G. A., Webb, S. C. & Clement, D. M. Bivalve aquaculture in estuaries: Review and synthesis of oyster cultivation effects. Aquaculture 298, 1–15 (2009).

Solomon, O. O. & Ahmed, O. O. Ecological consequences of oysters culture: a review. Int J. Fish. Aquat. 4, 01–06 (2016).

Pezy, J.-P., Delecrin, C., Baffreau, A., Basuyaux, O. & Dauvin, J.-C. Anthropogenic impact of oyster farming on macrofauna biodiversity in an eelgrass (Zostera marina) ecosystem of the English Channel. Ecol. Indic. 106, 105480 (2019).

Cooney, R., Tahar, A., Kennedy, A. & Clifford, E. Impact and recovery of water quality in a river with salmon aquaculture. Aquac. Fish. 4, e142 (2023).

Ziegler, F. et al. The carbon footprint of Norwegian seafood products on the global seafood market. J. Indus Eco. 17, 103–116 (2013).

European Commission. Commission recommendation of 16.12.2021 on the use of the Environmental Footprint Methods to Measure and Communicate the Life Cycle Environmental Performance of Products and Organisations (2021). Available from https://environment.ec.europa.eu/publications/recommendation-use-environmental-footprint-methods_en (Accessed 15 November 2023).

Frischknecht, R., Büsser Knöpfel, F. W. S., Lützkendorf, T. & Balouktsi, M. Cumulative energy demand in LCA: the energy harvested approach. Int J. Life Cycle Assess. 20, 957–969 (2015).

Aubin, J. Life cycle assessment as applied to environmental choices regarding farmed or wild-caught fish. CAB Rev. 8 https://doi.org/10.1079/PAVSNNR20138011 (2013).

Vélez-Henao, J. A., Weinland, F. & Reintjes, N. Life cycle assessment of aquaculture bivalve shellfish production—a critical review of methodological trends. Int J. Life Cycle Assess. 26, 1943–1958 (2021).

European Commission. A Study to examine the costs and benefits of the ELV Directive- Annex 5: Environmental Impacts and Characterisation Factors.” A study to examine the benefits of the End of Life Vehicles Directive (ELV) and the costs and benefits of a revision of the 2015 targets for recycling, re-Use and recovery under the ELV Directive—final report to the DG Environment. 6 (2006). Available from https://ec.europa.eu/environment/pdf/waste/study/annex5.pdf (Accessed 15 November 2023).

Acknowledgements

The present study was part of the ShellAqua project (BIM-21/KGS/001) funded under the Bord Iascaigh Mhara’s Knowledge Gateway Scheme, which is co-financed by the national exchequer: Ireland’s EU structure funds programme (ESIF) 2014-2020 & the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF). The authors would also like to acknowledge funding from InterReg Atlantic Areas ERDF (NEPTUNUS-EAPA_576/2018). The Networking initiative and open access is funded by the Marine Institute under the Marine Research Programme with the support of the Government of Ireland. The authors would like to thank the commercial Irish oyster farms contributing to the data collection for this study.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Domech, P.C., Cooney, R., Tahar, A. et al. Oysters, a sustainable bluefood?. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 24 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00065-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00065-1