Abstract 抽象

Peroxisomes are involved in multiple metabolic processes, including fatty acid oxidation, ether lipid synthesis and ROS metabolism. Recent studies suggest that peroxisomes are critical mediators of cellular responses to various forms of stress, including oxidative stress, hypoxia, starvation, cold exposure, and noise. As dynamic organelles, peroxisomes can modulate their proliferation, morphology, and movement within cells, and engage in crosstalk with other organelles in response to external cues. Although peroxisome-derived hydrogen peroxide plays a key role in cellular signaling related to stress, emerging studies suggest that other products of peroxisomal metabolism, such as acetyl-CoA and ether lipids, are also important for metabolic adaptation to stress. Here, we review molecular mechanisms through which peroxisomes regulate metabolic and environmental stress.

过氧化物酶体参与多种代谢过程,包括脂肪酸氧化、醚脂合成和 ROS 代谢。最近的研究表明,过氧化物酶体是细胞对各种形式压力(包括氧化应激、缺氧、饥饿、寒冷暴露和噪音)反应的关键介质。作为动态细胞器,过氧化物酶体可以调节它们在细胞内的增殖、形态和运动,并响应外部线索与其他细胞器进行串扰。尽管过氧化物酶体衍生的过氧化氢在与压力相关的细胞信号传导中起着关键作用,但新兴研究表明,过氧化物酶体代谢的其他产物,例如乙酰辅酶 A 和醚脂,对于代谢适应压力也很重要。在这里,我们回顾了过氧化物酶体调节代谢和环境应激的分子机制。

Keywords: Ether lipid, lipid metabolism, peroxisome, stress, plasmalogen, reactive oxygen species

关键字: 醚脂、脂质代谢、过氧化物酶体、应激、缩醛磷、活性氧

A snapshot of the peroxisomal compartment

过氧化物酶体隔室的快照

Peroxisomes are single membrane-enclosed organelles that exist in almost all eukaryotic cells. As a highly dynamic organelle, peroxisomes can adapt their shape, size, location and abundance in response to the nutritional or environmental cues [1]. Peroxisomal homeostasis is regulated by a delicate balance between formation of new peroxisomes and autophagic degradation of existing peroxisomes, or pexophagy (see Glossary)[2]. The removal of superfluous or dysfunctional peroxisomes is thought to help maintain proper peroxisome function and prevent accumulation of damage during cellular aging [3]. New peroxisomes can be derived from division of existing peroxisome or via de novo biogenesis (Box 1). Peroxisomes carry out various metabolic functions, including catabolism of very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA), branched chain fatty acids, D-amino acids, and polyamines, production and catabolism of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and biosynthesis of ether lipids and bile acids [1]. Some of these functions require cooperation with other organelles (Figure 1). For example, peroxisomal β-oxidation of VLCFA is thought to be a chain-shortening process, with the completion taking place in mitochondria (Box 2). Synthesis of ether lipids, including plasmalogens, initiates in peroxisomes and is completed in the ER (Box 3). Peroxisomes have also been shown to interact with lysosomes for transport of free cholesterol [4].

过氧化物酶体是几乎存在于所有真核细胞中的单膜封闭细胞器。作为一种高度动态的细胞器,过氧化物酶体可以根据营养或环境线索调整其形状、大小、位置和丰度 [ 1 ]。过氧化物酶体稳态受新过氧化物酶体的形成与现有过氧化物酶体的自噬降解或异食之间的微妙平衡的调节(见 Glossary )[ 2 ]。去除多余或功能失调的过氧化物酶体被认为有助于维持适当的过氧化物酶体功能并防止细胞衰老过程中损伤的积累[ 3 ]。新的过氧化物酶体可以来自现有过氧化物酶体的分裂或通过从头生物发生 ( Box 1 )。过氧化物酶体具有多种代谢功能,包括极长链脂肪酸(VLCFA)、支链脂肪酸、D-氨基酸和多胺的分解代谢、 活性氧(ROS) 的产生和分解代谢,以及醚脂和胆汁酸的生物合成[ 1 ]。其中一些功能需要与其他细胞器合作 ( Figure 1 )。例如,VLCFA 的过氧化物酶体 β 氧化被认为是一个链缩短过程,完成发生在线粒体中 ( Box 2 )。醚脂(包括缩醛磷脂 )的合成在过氧化物酶体中开始并在内质网中完成 ( Box 3 )。过氧化物酶体也被证明与溶酶体相互作用以转运游离胆固醇 [ 4 ]。

Box 1. Peroxisomal biogenesis.

方框 1.过氧化物酶体生物发生。

Peroxisomal biogenesis, the de novo formation of peroxisomes, requires multiple proteins called peroxins or Pex proteins. Approximately 30 such proteins have been identified and many of which are conserved from yeast to mammals and control different aspects of peroxisomal biogenesis [2]. Peroxisomal matrix proteins are translated on free ribosomes in the cytoplasm and have to be imported into peroxisomes. These proteins possess either a carboxyl terminal peroxisomal targeting sequence (PTS1) consisting of the SKL tripeptide (or a conserved variant) or an internal targeting sequence (PTS2) with the consensus sequence of (R/K)(L/V/I)X5(Q/H)(L/A). Pex5 is the import receptor for PTS1-containing peroxisomal matrix proteins [14], while Pex7 is required for transport of PTS2-containing matrix proteins [68]. A longer isoform of Pex5 (Pex5L) also serves as a co-receptor for Pex7 and targets the PTS2—Pex7 complex to peroxisomes [69]. Docking of the cytosolic PTS receptor/cargo complex at the peroxisomal membrane and release of the cargo into the peroxisomal lumen requires Pex13 and Pex14 [70]. Following the import of matrix proteins, Pex5 and Pex7 are recycled back to the cytosol in a process dependent on an exporter complex consisting of Pex1 and Pex6, which are recruited to the peroxisomal membrane by Pex26 [71, 72]. Cysteine mono-ubiquitination in Pex5 mediated by the RING-type ubiquitin ligases Pex2, Pex10 and Pex12 is required for recycling of the PTS1 receptor [73, 74]. The assembly of peroxisomal membrane and import of peroxisomal membrane proteins (PMPs) necessary for the formation of functional peroxisomes capable of importing matrix proteins involves fusion of a pre-peroxisomal vesicle derived from the ER with a vesicle derived from mitochondria. In mammalian cells, Pex16 buds from the ER in a pre-peroxisomal vesicle and fuses with a Pex3-containing precursor vesicle derived from mitochondria [75, 76]. Import of newly synthesized PMPs requires Pex19, a cytosolic chaperone and import receptor [77]. Loss of functions mutations in Pex3, Pex16 or Pex19 result in a complete absence of peroxisomes and cause peroxisomal biogenesis disorders in the Zellweger spectrum, which are devastating diseases characterized by severe liver dysfunction, developmental delay, neurological abnormalities and early death (generally before 2 years of age) [78, 79].

过氧化物酶体生物发生,即过氧化物酶体的从头形成,需要多种称为过氧化物酶或 Pex 蛋白的蛋白质。已经鉴定出大约 30 种此类蛋白质,其中许多从酵母到哺乳动物都是保守的,并控制过氧化物酶体生物发生的不同方面 [ 2 ]。过氧化物酶体基质蛋白在细胞质中的游离核糖体上翻译,必须导入过氧化物酶体。这些蛋白质具有由 SKL 三肽(或保守变体)组成的羧基末端过氧化物酶体靶向序列 (PTS1) 或具有共有序列 (R/K)(L/V/I)X5(Q/H)(L/A)。Pex5 是含 PTS1 的过氧化物酶体基质蛋白的输入受体 [ 14 ],而 Pex7 是转运含 PTS2 基质蛋白所必需的 [ 68 ]。Pex5 的较长亚型 (Pex5L) 也可作为 Pex7 的共受体,并将 PTS2—Pex7 复合物靶向过氧化物酶体 [ 69 ]。胞质 PTS 受体/货物复合物在过氧化物酶体膜上对接并将货物释放到过氧化物酶体管腔中需要 Pex13 和 Pex14[ 70 ]。在输入基质蛋白后,Pex5 和 Pex7 在依赖于由 Pex1 和 Pex6 组成的输出复合物的过程中被回收回细胞质,这些复合物被 Pex26 募集到过氧化物酶体膜上 [ 71 , 72 ]。PTS1 受体的回收需要由 RING 型泛素连接酶 Pex2,Pex10 和 Pex12 介导的 Pex5 中的半胱氨酸单泛素化[ 73 , 74 ]。 过氧化物酶体膜的组装和过氧化物酶体膜蛋白(PMP)的导入是形成能够输入基质蛋白的功能性过氧化物酶体所必需的,涉及源自内质网的前过氧化物酶体囊泡与源自线粒体的囊泡的融合。在哺乳动物细胞中,Pex16 从过氧化物酶体前囊泡中的 ER 萌芽,并与源自线粒体的含有 Pex3 的前体囊泡融合 [ 75 , 76 ]。新合成的 PMP 的导入需要 Pex19,一种胞质伴侣和导入受体[ 77 ]。Pex3、Pex16 或 Pex19 的功能丧失突变导致过氧化物酶体完全缺失,并导致齐薇格谱中的过氧化物酶体生物发生障碍,这是一种破坏性疾病,其特征是严重的肝功能障碍、发育迟缓、神经系统异常和过早死亡(通常在 2 岁之前)[ 78 , 79 ]。

Box 1, Figure I. Peroxisomal biogenesis pathway.

方框 1,图 I. 过氧化物酶体生物发生途径。

De novo formation of peroxisomes requires fusion of a pre-peroxisomal vesicle derived from the ER with a vesicle derived from the mitochondria, followed by import of peroxisomal matrix and membrane proteins. Abbreviations: PMP, peroxisomal membrane protein; PTS1, peroxisomal targeting sequence 1-containing matrix protein; PTS2, peroxisomal targeting sequence 2-containing matrix protein; Ub, ubiquitination.

过氧化物酶体的从头形成需要将源自内质网的前过氧化物酶体囊泡与源自线粒体的囊泡融合,然后导入过氧化物酶体基质和膜蛋白。缩写:PMP,过氧化物酶体膜蛋白;PTS1,过氧化物酶体靶向序列 1 含基质蛋白;PTS2,过氧化物酶体靶向序列 2 的基质蛋白;Ub,泛素化。

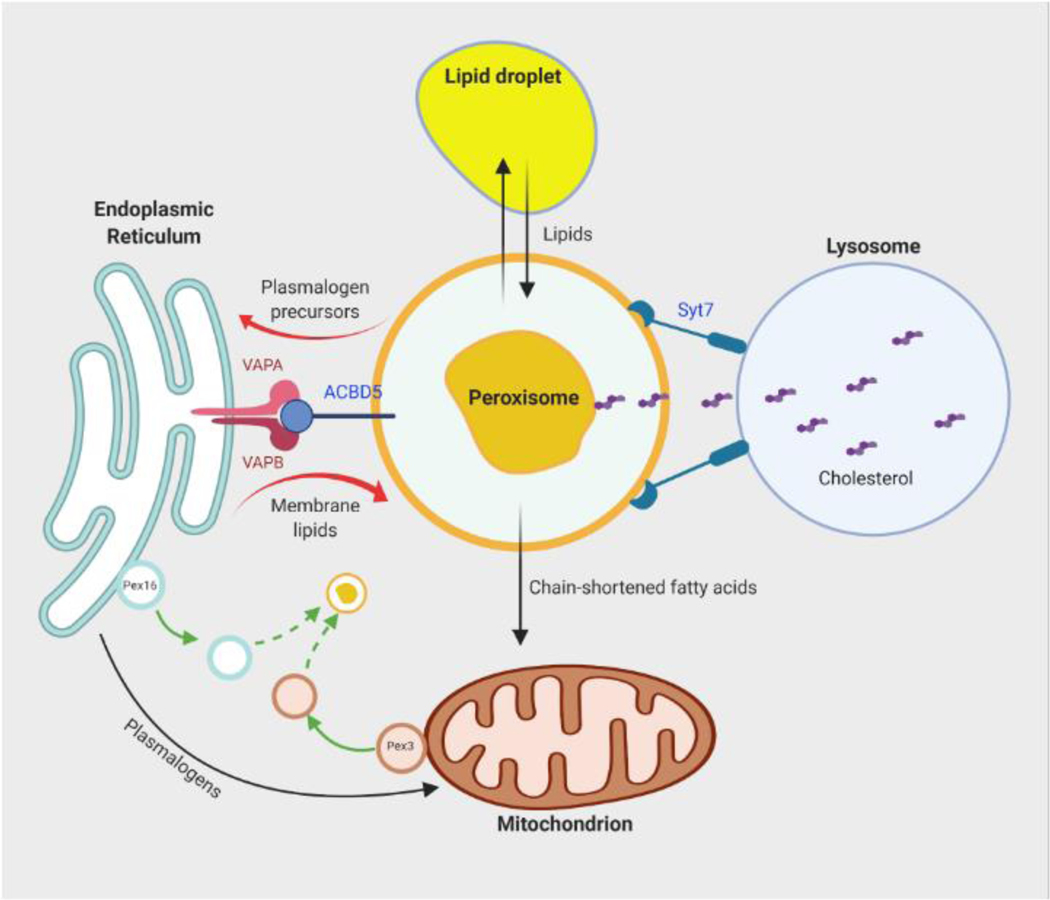

Figure 1. Crosstalk between peroxisomes and other organelles.

图 1.过氧化物酶体和其他细胞器之间的串扰。

Peroxisomal biogenesis and functions involves inter-organelle communication. De novo formation of peroxisomes involves fusion of precursor vesicles derived from the ER and mitochondria. Peroxisomes closely interact and exchange lipids with lipid droplets. Synthesis of ether lipids, such as plasmalogens, initiates in peroxisomes but is completed in the ER. The ER-peroxisome metabolite exchange may be assisted by the bridge formed by the membrane proteins VAPA, VAPB and ACBD5. Peroxisomes are also closely associated with mitochondria. Peroxisome-derived plasmalogens are found in mitochondrial membranes and may be involved in mitochondrial dynamics. Mitochondria help to further oxidize chain-shortened fatty acids produced by peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation. Peroxisomes also interact with lysosomes through the membrane protein Syt7, which promotes transfer of free cholesterol from lysosomes to peroxisomes. Abbreviations: ER, endoplasmic reticulum; VAPA and VAPB, VAMP-associated proteins A and B; ACBD5, acyl-CoA binding domain containing protein 5; Syt7, synaptotagmin 7.

过氧化物酶体的生物发生和功能涉及细胞器间通讯。过氧化物酶体的从头形成涉及源自内质网和线粒体的前体囊泡的融合。过氧化物酶体与脂滴密切相互作用并交换脂质。醚脂(例如缩醛磷脂)的合成始于过氧化物酶体,但在内质网中完成。ER-过氧化物酶体代谢物交换可能由膜蛋白 VAPA、VAPB 和 ACBD5 形成的桥梁辅助。过氧化物酶体也与线粒体密切相关。过氧化物酶体衍生的缩醛磷脂存在于线粒体膜中,可能参与线粒体动力学。线粒体有助于进一步氧化过氧化物酶体脂肪酸氧化产生的链缩短脂肪酸。过氧化物酶体还通过膜蛋白 Syt7 与溶酶体相互作用,从而促进游离胆固醇从溶酶体转移到过氧化物酶体。缩写:ER,内质网;VAPA 和 VAPB,VAMP 相关蛋白 A 和 B;ACBD5,酰基辅酶 A 结合结构域,含有蛋白 5;Syt7,突触蛋白 7。

Box 2. Peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway.

方框 2.过氧化物酶体β氧化途径。

In mammalian cells, fatty acids can be catabolized via β-oxidation in mitochondria and peroxisomes. Very long chain fatty acids (C≥22) are exclusively oxidized in peroxisomes [80]. This process requires the fatty acid to be first activated to an acyl-CoA by acyl-CoA synthetase (ACSL) in the presence of ATP. Acyl-CoA, transported into the peroxisomal matrix via ATP binding cassette transporter D subfamily of proteins (ABCD1–3), is oxidized to trans-2-enoyl-CoA by Acox1, an FAD-dependent oxidase that generates H2O2 as a byproduct. Related enzymes Acox2 and Acox3 are involved in oxidation of branched chain fatty acids and intermediates involved in bile acid synthesis. Trans-2-enoyl-CoA is further reacted to chiral 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA and 3-ketoacyl-CoA sequentially by the peroxisomal multifunctional enzyme 1 or 2 (MFE1/2), which possesses enoyl-CoA hydratase and 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase activities. In the final step, 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase promotes cleavage of the terminal acetyl-CoA group, forming a new acyl-CoA molecule that has been shortened by two carbon atoms. After several rounds of peroxisomal β-oxidation, the chain-shortened fatty acid is shuttled into mitochondria by either carnitine-dependent or -independent routes to undergo further rounds of β-oxidation [81].

在哺乳动物细胞中,脂肪酸可以通过线粒体和过氧化物酶体中的β氧化分解代谢。极长链脂肪酸 (C≥22) 仅在过氧化物酶体中氧化 [ 80 ]。该过程要求脂肪酸首先在 ATP 存在下通过酰基辅酶 A 合成酶 (ACSL) 激活为酰基辅酶 A。酰基辅酶 A 通过 ATP 结合盒转运蛋白 D 亚家族(ABCD1-3)转运到过氧化物酶体基质中,被 Acox1 氧化成反式-2-烯酰辅酶 A,Acox1 是一种 FAD 依赖性氧化酶,可产生 H2O2 作为副产物。相关酶 Acox2 和 Acox3 参与支链脂肪酸的氧化和参与胆汁酸合成的中间体。反式-2-烯酰辅酶 A 通过具有烯酰辅酶 A 水合酶和 3-羟酰辅酶 A 脱氢酶活性的过氧化物酶体多功能酶 1 或 2(MFE1/2)依次与手性 3-羟酰辅酶 A 和 3-酮酰辅酶 A 反应。在最后一步中,3-酮酰基辅酶 A 硫醇酶促进末端乙酰辅酶 A 基团的裂解,形成一个新的酰基辅酶 A 分子,该分子已被两个碳原子缩短。经过几轮过氧化物酶体β氧化后,链缩短的脂肪酸通过肉碱依赖性或非依赖性途径穿梭在线粒体中,进行进一步的β氧化[ 81 ]。

Box 2, Figure I. Peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway.

方框 2,图 I. 过氧化物酶体β氧化途径。

Very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA) are activated to acyl-CoA and imported by peroxisomes for β-oxidation. Each cycle of fatty acid oxidation shortens the acyl chain by 2 carbons with the thiolytic cleavage of the terminal acetyl-CoA.

极长链脂肪酸 (VLCFA) 被激活为酰基辅酶 A,并被过氧化物酶体导入进行β氧化。脂肪酸氧化的每个循环都会随着末端乙酰辅酶 A 的硫解裂解使酰基链缩短 2 个碳。

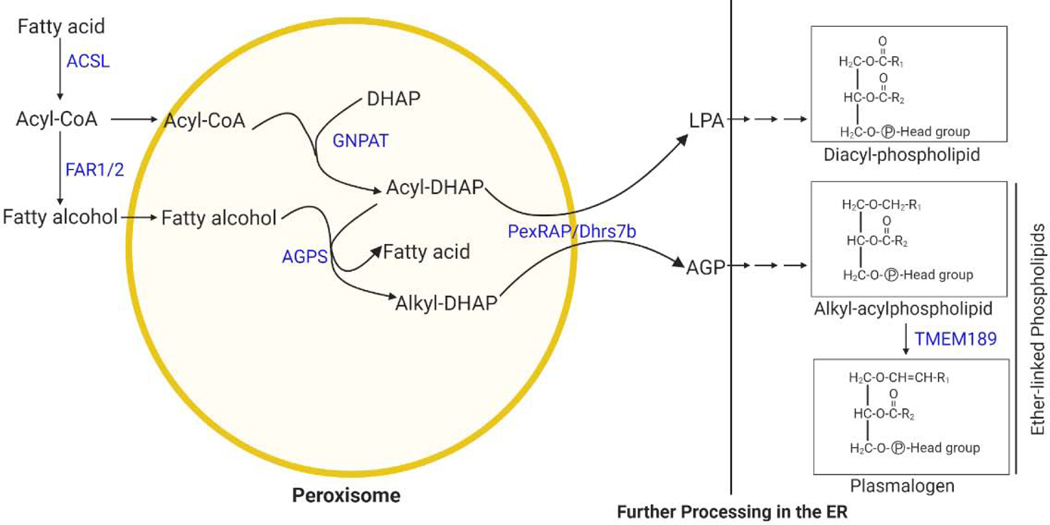

Box 3. Plasmalogen synthetic pathway.

方框 3.疟原蛋白合成途径。

Plasmalogens are the most common form of a subclass of glycerophospholipids called ether lipids that have an alkyl chain attached to the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone by an ether bond as opposed to an acyl chain attached by an ester bond in conventional glycerophospholipids, such as phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine [82]. Plasmalogens are characterized by a cis double bond adjacent to the ether linkage. Plasmalogen synthesis begins in peroxisomes, involving the acyl-dihydroxyacetone (DHAP) pathway, since the glycolysis intermediate DHAP is used as a precursor for ether lipid synthesis [83]. The process begins when glyceronephosphate O-acyltransferase (GNPAT), a peroxisomal matrix protein, esterifies DHAP with a long chain acyl-CoA at the sn-1 position. The next step is catalyzed by alkylglycerone phosphate synthase (AGPS), another peroxisomal protein, and results in the formation of the hallmark ether bond at the sn-1 position by exchanging an acyl chain for an alkyl group. The alkyl component used by AGPS is generated by a peroxisomal membrane-associated fatty acyl-CoA reductase (FAR1/FAR2), which reduces an acyl-CoA to a fatty alcohol. The final peroxisomal step is carried out by the acyl/alkyl-DHAP reductase PexRAP/DHRS7b, which reduces alkyl- or acyl-DHAP into the ether lipid precursor 1-O-alkyl glycerol-3-phosphate (AGP) or lysophophatidic acid (LPA), a precursor of conventional diacylphospholipids [84, 85]. Further steps to process AGP or LPA into their corresponding ether-linked or diacyl glycerolipids take place in the ER [83, 86]. Several potential modes have been proposed for how AGP is transported to ER for completion of plasmalogen synthesis, including involving use of a lipid-binding protein, specific shuttle vesicle, or direct membrane contact [87, 88]. In support the last mode, disruption of the VAP-ACBD5 tether between peroxisome and ER leads to decreased plasmalogen synthesis [89]. The ER steps involved in plasmalogen synthesis are less understood, but enzymes which modify the sn2 and sn3 positions during plasmalogen biosynthesis may be shared between ether- and ester-linked glycerolipids. Recently, TMEM189 was identified as the gene encoding a plasmanylethanolamine desaturase (PEDS), which is required for ethanolamine plasmalogen biosynthesis through insertion of the alk-1′-enyl ether or “vinyl-ether” double bond that is characteristic of plasmalogens [90, 91].

疟原蛋白是甘油磷脂亚类(称为醚脂)的最常见形式,其烷基链通过醚键连接到甘油主链的 sn-1 位置,而不是传统甘油磷脂(如磷脂酰胆碱和磷脂酰乙醇胺)中通过酯键连接的酰基链 [ 82 ].缩醛磷脂的特征是与醚键相邻的顺式双键。缩醛磷脂的合成始于过氧化物酶体,涉及酰基-二羟基丙酮(DHAP)途径,因为糖酵解中间体 DHAP 被用作醚脂合成的前体[ 83 ]。当甘油磷酸 O-酰基转移酶 (GNPAT)(一种过氧化物酶体基质蛋白)在 sn-1 位置用长链酰基辅酶 A 酯化 DHAP 时,该过程就开始了。下一步由烷基甘油磷酸合酶(另一种过氧化物酶体蛋白)催化,并通过将酰基链交换为烷基,在 sn-1 位置形成标志性的醚键。AGPS 使用的烷基组分是由过氧化物酶体膜相关脂肪酰基辅酶 A 还原酶 (FAR1/FAR2) 产生的,该酶将酰基辅酶 A 还原为脂肪醇。最后的过氧化物酶体步骤由酰基/烷基-DHAP 还原酶 PexRAP/DHRS7b 进行,该酶将烷基或酰基-DHAP 还原为醚脂前体 1-O-烷基甘油-3-磷酸(AGP)或溶血磷酸(LPA),这是传统二氧基磷脂的前体[ 84 , 85 ]。将 AGP 或 LPA 加工成其相应的醚连接或二酰甘油脂的进一步步骤发生在内质网[ 83 , 86 ]。 对于如何将 AGP 转运到 ER 以完成缩醛磷脂合成,已经提出了几种潜在的模式,包括涉及使用脂质结合蛋白、特异性穿梭囊泡或直接膜接触 [ 87 , 88 ]。在支持最后一种模式下,过氧化物酶体和内质网之间的 VAP-ACBD5 拴绳的破坏导致缩醛磷脂合成减少[ 89 ]。胶质磷脂合成中涉及的内质网步骤知之甚少,但在缩醛磷脂生物合成过程中改变 sn2 和 sn3 位置的酶可能在醚和酯连接的甘油脂之间共享。最近,TMEM189 被鉴定为编码纤溶酶乙醇胺去饱和酶 (PEDS) 的基因,该基因是乙醇胺缩醛磷脂生物合成所必需的,通过插入 alk-1'-烯基醚或“乙烯基醚”双键,这是缩醛磷脂的特征 [ 90 , 91 ]。

Box 3, Figure I. Ether lipid synthetic pathway.

方框 3,图 I. 醚脂合成途径。

The initial steps of ether lipid synthesis take place in peroxisomes, generating 1-O-alkyl glycerol-3-phosphate (AGP), a precursor of ether lipids. The subsequent steps take place in the ER. Peroxisomes can also generate lysophophatidic acid (LPA), a precursor of conventional diacylphospholipids.

醚脂合成的初始步骤发生在过氧化物酶体中,生成 1-O-烷基甘油-3-磷酸 (AGP),这是醚脂的前体。后续步骤在内质网中进行。过氧化物酶体还可以产生溶血磷脂酸 (LPA),这是传统二氧基磷脂的前体。

In addition to these metabolic functions, emerging studies have uncovered a role for peroxisomes in metabolic adaptation to stress. In light of these recent findings, here we review molecular mechanisms through which peroxisomes regulate cellular stress response. The role of peroxisomes as sensors of stress is first briefly introduced, along with a discussion of key peroxisome-derived signaling molecules. Next, the review highlights recent important papers describing molecular mechanisms through which peroxisomes are involved in various forms of metabolic and environmental stress. The article concludes with a discussion of pertinent directions for future research and the translational potential of targeting peroxisomal regulation of stress response.

除了这些代谢功能外,新兴研究还揭示了过氧化物酶体在代谢适应压力中的作用。鉴于这些最近的发现,我们在这里回顾了过氧化物酶体调节细胞应激反应的分子机制。首先简要介绍了过氧化物酶体作为压力传感器的作用,并讨论了关键的过氧化物酶体衍生的信号分子。接下来,该综述重点介绍了最近描述过氧化物酶体参与各种形式的代谢和环境应激的分子机制的重要论文。文章最后讨论了未来研究的相关方向以及靶向过氧化物酶体调节应激反应的转化潜力。

Peroxisomes as mediators of cellular stress response

过氧化物酶体作为细胞应激反应的介质

All organisms have evolved a capacity to maintain homeostasis, which can be disturbed by adverse forces called stressors [5]. Stress can be caused by environmental factors or metabolic disturbances. Environmental stressors include extreme temperature, noise, toxins and pathogens. Metabolic stress is driven by metabolic disturbances and can be influenced by environmental fluctuations and include nutrient stress (excess or deficiency), oxidative stress, and hypoxia. Increasing evidence suggests that peroxisomes are critical sensors of stress. The highly plastic nature of peroxisomes, their capacity to perform a diverse variety of functions, and their ability to communicate with other organelles either via direct physical interactions or through exchange of metabolites make these organelles well-suited to serve as a signaling node that controls cellular responses to stress. Although peroxisome-derived hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) plays a key role in cellular signaling related to stress, emerging studies suggest that others products of peroxisomal metabolism, such as acetyl-CoA and ether lipids, are also important for metabolic adaptation to stress. In the next two sections, we review molecular mechanisms through which peroxisomes regulate different forms of metabolic and environmental stress.

所有生物体都进化出维持体内平衡的能力,这种能力可能会受到称为压力源的不利力量的干扰 [ 5 ]。压力可能是由环境因素或代谢紊乱引起的。环境压力源包括极端温度、噪音、毒素和病原体。代谢应激是由代谢紊乱驱动的,并可能受到环境波动的影响,包括营养应激(过量或缺乏)、氧化应激和缺氧。越来越多的证据表明,过氧化物酶体是压力的关键传感器。过氧化物酶体的高度可塑性、执行多种功能的能力以及通过直接物理相互作用或代谢物交换与其他细胞器进行交流的能力,使这些细胞器非常适合作为控制细胞对压力反应的信号节点。尽管过氧化物酶体衍生的过氧化氢 (H2O2) 在与压力相关的细胞信号传导中起着关键作用,但新兴研究表明,过氧化物酶体代谢的其他产物,如乙酰辅酶 A 和醚脂,对于代谢适应压力也很重要。在接下来的两节中,我们将回顾过氧化物酶体调节不同形式的代谢和环境应激的分子机制。

Peroxisomal response to metabolic stress

过氧化物酶体对代谢应激的反应

Recent findings suggest peroxisomes are not only passive performers of various metabolic reactions, but also a signaling hub that integrates signals derived from these metabolic reactions to respond to metabolic stressors. In this section, we discuss the mechanisms through which peroxisomes act as a source or a regulator of oxidative stress, how they affect cellular fitness during hypoxic stress, and how they control lipid hydrolysis during nutrient deprivation.

最近的研究结果表明,过氧化物酶体不仅是各种代谢反应的被动执行者,而且还是一个信号中心,整合了来自这些代谢反应的信号以响应代谢应激源。在本节中,我们讨论过氧化物酶体作为氧化应激来源或调节剂的机制,它们如何在缺氧应激期间影响细胞健康,以及它们如何在营养剥夺期间控制脂质水解。

Regulation of oxidative stress by peroxisomes

过氧化物酶体对氧化应激的调节

Peroxisomes derive their name from their role in H2O2 metabolism. Peroxisomal respiration accounts for up to 20% of total cellular oxygen consumption and produces as much as 35% of total H2O2 in certain mammalian tissues [6] through the actions of multiple FAD-dependent oxidoreductases present in these organelles. To counteract the damaging effects of ROS, peroxisomes contain several antioxidant enzymes, including catalase, which reduces H2O2 to water. Disruption of the balance between peroxisomal ROS production and removal leads to oxidative stress and is associated with a variety of age-related human diseases, including diabetes, cancer, and neurological disorders [7–9]. For example, humans with a gain of function mutation (N237S) in Acox1 (acyl CoA oxidase 1), a peroxisomal enzyme that oxidizes VLCFA and produces H2O2 as a byproduct, exhibit loss of glia and neurodegeneration. Mimicking the human disease, a Drosophila model of this mutation, which promotes dimerization of the enzyme, leads to increased ROS production in glia, resulting in glial and axonal loss and increased lethality, which could be rescued by treatment with the antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine amide [10]. Increased ROS production by the active Acox1 dimer has also been implicated in DNA damage and cancer in a process dependent on sirtuin 5 (SIRT5) [11]. SIRT5 was shown to be localized in peroxisomes, where it interacts with Acox1 and promotes its desuccinylation and inhibits its activity through suppression of dimer formation. SIRT5 protein level is downregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma tumor compared to peritumor tissues, while Acox1 activity is upregulated due to increased succinylation of the β-oxidation enzyme. Knockdown of SIRT5 in human cancer cell lines increases H2O2 production and oxidative DNA damage in an Acox1-dependent manner [11]. It remains to be determined whether the peroxisomal localization of SIRT5, a predominantly mitochondrial and cytosolic enzyme [12], is regulated by oxidative stress.

过氧化物酶体因其在 H2O2 代谢中的作用而得名。过氧化物酶体呼吸占细胞总耗氧量的 20%,并通过这些细胞器中存在的多种 FAD 依赖性氧化还原酶的作用,在某些哺乳动物组织中产生多达 35% 的总 H2O2 [ 6 ]。为了抵消 ROS 的破坏作用,过氧化物酶体含有多种抗氧化酶,包括过氧化氢酶,可将 H2O2 还原为水。过氧化物酶体 ROS 产生和去除之间平衡的破坏会导致氧化应激,并与多种与年龄相关的人类疾病有关,包括糖尿病、癌症和神经系统疾病 [ 7 – 9 ]。例如,Acox1(酰基辅酶 A 氧化酶 1)功能获得突变(N237S)的人类,Acox1(一种氧化 VLCFA 并产生 H2O2 作为副产物的过氧化物酶)表现出神经胶质细胞丧失和神经变性。模拟人类疾病,这种突变的果蝇模型促进酶的二聚化,导致神经胶质细胞中 ROS 的产生增加,导致神经胶质细胞和轴突丢失以及致死率增加,这可以通过用抗氧化剂 N-乙酰半胱氨酸酰胺处理来挽救[ 10 ]。活性 Acox1 二聚体增加 ROS 的产生也与 DNA 损伤和癌症有关,这一过程依赖于去乙醯化酶 5(SIRT5)[ 11 ]。SIRT5 被证明定位于过氧化物酶体中,它与 Acox1 相互作用并促进其去琥珀酰化并通过抑制二聚体形成来抑制其活性。 与肿瘤周围组织相比,肝细胞癌肿瘤中的 SIRT5 蛋白水平下调,而 Acox1 活性由于β氧化酶的琥珀酰化增加而上调。敲低人癌细胞系中 SIRT5 会以 Acox1 依赖性方式增加 H2O2 的产生和氧化 DNA 损伤[ 11 ]。SIRT5(一种主要在线粒体和胞质 12 酶)的过氧化物酶体定位是否受氧化应激调节仍有待确定。

Genome-wide shRNA and CRISPR-Cas9 screens to discover regulators of oxidative stress identified known regulators of cellular redox balance, such as various antioxidant enzymes, but also led to the identification of several proteins involved in the peroxisomal import pathway, including Pex5, Pex13 and Pex14, as modifiers of cellular sensitivity to oxidative stress [13]. Of note, Pex5 is the import receptor of peroxisomal matrix proteins, including catalase, which contain a carboxyl terminal peroxisomal targeting sequence (PTS1) [14]. Paradoxically, inactivation of Pex5, which results in redistribution of catalase to the cytoplasm, increased resistance to oxidative stress caused by exogenous H2O2 treatment. Furthermore, ROS-induced phosphorylation of Pex14 at Ser232 impairs the interaction between the Pex5-Pex14 complex and catalase, confining catalase in the cytosol to counteract oxidative stress [15]. Indeed, a mutant of catalase localized to the cytoplasm was more protective against cell death caused by ROS as compared to the peroxisome-localized antioxidant enzyme [13]. This suggests that cytoplasmic catalase might be important for protection against acute oxidative stress, while peroxisomal catalase could be more involved in controlling basal oxidative stress resulting from peroxisome-generated ROS. This is consistent with previous studies suggesting that Pex5 itself is a redox-sensitive protein that exhibits reduced ability to import catalase under acute oxidative stress [16] and that the proapoptotic BCL-2 effector protein BAK promotes peroxisomal membrane permeabilization and localization of catalase in the cytosol during oxidative stress [17]. These studies support the notion that peroxisomes can function as a source or a sink of ROS, depending on physiological context [9]. The balance between ROS generation and elimination requires peroxisomal homeostasis, which in turn is maintained through a delicate balance between biogenesis and turnover of peroxisomes.

全基因组 shRNA 和 CRISPR-Cas9 筛选以发现氧化应激调节因子,鉴定了细胞氧化还原平衡的已知调节因子,例如各种抗氧化酶,但也鉴定了参与过氧化物酶体输入途径的几种蛋白质,包括 Pex5、Pex13 和 Pex14,作为细胞对氧化应激敏感性的修饰因子 [ 13 ].值得注意的是,Pex5 是过氧化物酶体基质蛋白(包括过氧化氢酶)的输入受体,过氧化氢酶含有羧基末端过氧化物酶体靶向序列(terboxyl terminal peroxisomal targeting sequence, PTS1)[ 14 ]。矛盾的是,Pex5 的失活导致过氧化氢酶重新分布到细胞质,增加了对外源性 H2O2 处理引起的氧化应激的抵抗力。此外,ROS 诱导的 Pex14 在 Ser232 处的磷酸化损害了 Pex5-Pex14 复合物与过氧化氢酶之间的相互作用,将过氧化氢酶限制在细胞质中以抵消氧化应激[ 15 ]。事实上,与过氧化物酶体定位的抗氧化酶相比,定位于细胞质的过氧化氢酶突变体对 ROS 引起的细胞死亡具有更强的保护作用[ 13 ]。这表明细胞质过氧化氢酶可能对防止急性氧化应激很重要,而过氧化物酶体过氧化氢酶可能更多地参与控制过氧化物酶体产生的 ROS 引起的基础氧化应激。这与先前的研究表明,Pex5 本身是一种氧化还原敏感蛋白,在急性氧化应激下输入过氧化氢酶的能力降低[ 16 ],并且促凋亡 BCL-2 效应蛋白 BAK 在氧化应激期间促进过氧化物酶体膜透化和过氧化氢酶在细胞质中的定位[ 17 ]。 这些研究支持过氧化物酶体可以作为 ROS 的来源或汇的观点,具体取决于生理背景[ 9 ]。ROS 生成和消除之间的平衡需要过氧化物酶体稳态,而过氧化物酶体稳态又通过过氧化物酶体的生物发生和周转之间的微妙平衡来维持。

Turnover of old or dysfunctional peroxisomes has also been linked to increased peroxisomal ROS production. In this regard, ATM (Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated) kinase, a redox sensitive regulator of nuclear DNA damage response [18, 19], was recently shown to interact with Pex5 and translocate to peroxisomes to regulate pexophagy in response to ROS [20]. Activated ATM phosphorylates Pex5 at Ser 141, which in turn promotes Pex5 ubiquitination at Lys 209. Peroxisomes containing ubiquitinated Pex5 are recognized by the autophagy adaptor p62 and targeted for degradation [20]. It remains unclear whether ATM is activated by ROS endogenously produced by peroxisomes. However, supporting the possibility that endogenous ROS promotes autophagic degradation of peroxisomes, activation of pexophagy caused by knockout of the heat shock protein HSPA9 has been linked to elevated accumulation of peroxisomal ROS detected using peroxisome-localized HyPer, a redox-sensitive fluorescent protein that can detect H2O2 [21]. One potential beneficial effect of ROS-induced pexophagy mediated by ATM could be the restoration of cellular redox balance to prevent ROS-induced DNA damage. In line with this notion, knockdown of catalase leads to the impairment of peroxisomal ROS removal and causes ROS-induced pexophagy, which can be rescued by the addition of the antioxidant agent N-acetyl-L-cysteine [22].

旧的或功能失调的过氧化物酶体的周转也与过氧化物酶体 ROS 产生增加有关。在这方面,ATM(共济失调-毛细血管扩张突变)激酶是核 DNA 损伤反应的氧化还原敏感调节因子 [ 18 , 19 ],最近被证明与 Pex5 相互作用并易位到过氧化物酶体以调节响应 ROS 的 pexophagagy [ 20 ]。激活的 ATM 在 Ser 141 处磷酸化 Pex5,进而促进 Lys 209 处的 Pex5 泛素化。含有泛素化 Pex5 的过氧化物酶体被自噬接头 p62 识别并靶向降解[ 20 ]。目前尚不清楚 ATM 是否由过氧化物酶体内源性产生的 ROS 激活。然而,支持内源性 ROS 促进过氧化物酶体自噬降解的可能性,由热休克蛋白 HSPA9 敲除引起的 pexophagage 激活与使用过氧化物酶体定位的 HyPer 检测到的过氧化物酶体 ROS 积累升高有关,HyPer 是一种氧化还原敏感荧光蛋白,可以检测 H2O2 [ 21 ].ATM 介导的 ROS 诱导的 pexophagy 的一个潜在有益作用可能是恢复细胞氧化还原平衡,以防止 ROS 诱导的 DNA 损伤。根据这一观点,过氧化氢酶的敲低会导致过氧化物酶体 ROS 去除受损,并引起 ROS 诱导的 pexophagage,这可以通过添加抗氧化剂 N-乙酰基-L-半胱氨酸来挽救[ 22 ]。

Role of peroxisomes in metabolic adaptation to hypoxic stress

过氧化物酶体在代谢适应缺氧应激中的作用

Oxygen is a critical substrate in cellular metabolism and bioenergetics. Inadequate availability of oxygen to tissues, or hypoxia, is experienced in various physiological and pathological states. For instance, tissue hypoxia is a prominent feature of most solid tumors that promotes tumor aggressiveness and metastasis [23, 24]. A genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 growth screen by Jain et al. [25] to discover regulators of cell fitness in high and low oxygen conditions led to the identification of an essential role for peroxisomes in metabolic adaptation to hypoxic stress. Notably, the authors observed that peroxisomal biogenesis genes Pex2, Pex5, Pex7, Pex10, Pex12, and Pex13 and plasmalogen synthesis genes GNPAT, AGPS, FAR1/2 and TMEM189 were selectively essential for growth in 1% O2 versus 21% O2. Plasmalogens are peroxisome-derived phospholipids which have a vinyl ether bond at the sn-1 position as opposed to an ester bond in the conventional phospholipids (Box 3). The cell growth defect under hypoxic stress was rescued with the addition of the unsaturated fattyacid oleate, but worsened with the saturated fatty acid palmitate [25]. This is notable since previous studies suggest that stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD), an enzyme that introduces a single double bond in the Δ9 position of saturated fatty acids, is an oxygen-sensitive protein inhibited by hypoxia. The resulting increased ratio of saturated to unsaturated fatty acids leads to impaired cell growth, presumably due to increased membrane rigidity [26, 27]. This led Jain et al. to propose that plasmalogens, which have been implicated in membrane fluidity [28], are beneficial in hypoxia to reduce membrane rigidity. Their lipidomics analysis indicated that biosynthesis of these peroxisome-derived lipids is increased in hypoxia [25]. It remains to be determined whether plasmalogens directly influence cellular fitness in the context of hypoxic stress via control of membrane fluidity. It is possible that other mechanisms might also be at play. For example, plasmalogens are thought to function as endogenous antioxidants [29, 30], which could affect hypoxia-related lipid peroxidation [31]. In line with this possibility, a genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screen coupled with lipidomic profiling to discover factors that impact susceptibility to ferroptosis led to the identification of polyunsaturated ether lipids, including plasmalogens, as substrates for lipid peroxidation that promote induction of ferroptosis, which carcinoma cells can evade through downregulation of these lipids [32].

氧气是细胞代谢和生物能量学中的关键底物。在各种生理和病理状态下,组织氧气供应不足或缺氧。例如,组织缺氧是大多数实体瘤的一个突出特征,可促进肿瘤的侵袭性和转移 [ 23 , 24 ]。Jain 等人 [ 25 ] 通过全基因组 CRISPR-Cas9 生长筛选,以发现高氧和低氧条件下细胞适应性的调节因子,从而确定了过氧化物酶体在代谢适应缺氧应激中的重要作用。值得注意的是,作者观察到过氧化物酶体生物发生基因 Pex2、Pex5、Pex7、Pex10、Pex12 和 Pex13 以及缩醛磷脂合成基因 GNPAT、AGPS、FAR1/2 和 TMEM189 对于 1% O2 与 21% O2 的生长具有选择性必要性。疟原蛋白是过氧化物酶体衍生的磷脂,在 sn-1 位具有乙烯基醚键,而不是传统磷脂中的酯键 ( Box 3 )。添加不饱和脂肪酸油酸酯可挽救缺氧胁迫下的细胞生长缺陷,但加入饱和脂肪酸棕榈酸酯可加重[ 25 ]。这一点值得注意,因为先前的研究表明,硬脂酰辅酶 A 去饱和酶 (SCD) 是一种在饱和脂肪酸的 Δ9 位引入单双键的酶,是一种因缺氧而抑制的氧敏感蛋白质。由此产生的饱和脂肪酸与不饱和脂肪酸比例增加导致细胞生长受损,可能是由于膜刚度增加 [ 26 , 27 ]。这导致 Jain 等人提出,与膜流动性有关的缩醛磷脂[ 28 ]有利于缺氧,从而降低膜刚度。 他们的脂质组学分析表明,这些过氧化物酶体衍生脂质的生物合成在缺氧时增加 [ 25 ]。在缺氧应激背景下,疟原是否通过控制膜流动性直接影响细胞适应性仍有待确定。其他机制也可能在起作用。例如,缩醛磷脂被认为具有内源性抗氧化剂的作用 [ 29 , 30 ],这可能会影响缺氧相关的脂质过氧化 [ 31 ]。与这种可能性一致,全基因组 CRISPR-Cas9 筛选与脂质组学分析相结合,以发现影响铁死亡易感性的因素,从而鉴定出多不饱和醚脂质,包括缩醛磷脂,作为脂质过氧化的底物,促进诱导铁死亡,癌细胞可以通过下调这些脂质来逃避铁死亡[ 32 ]。

It is remarkable that while acute exposure of cells to low oxygen conditions does not decrease peroxisome abundance [25], sustained activation of hypoxia via genetic inactivation of a critical regulatory factor dramatically decreases the number of peroxisomes [33]. Hypoxia is regulated by the hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) family of transcription factors, which are active under hypoxia but targeted for degradation by the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein under oxygen replete conditions. Activated HIF transcriptionally reprogram cells to adapt to the low oxygen tension environment [34]. Interestingly, the stabilization of HIF2α resulting from VHL knockout promotes pexophagy, leading to a dramatic reduction of peroxisome abundance [33]. The precise reason for the conflicting effects on peroxisome abundance remains unclear. However, chronic hypoxia has been shown to protect against the effects of acute hypoxia [35, 36]. Thus, it is possible that induction of pexophagy as a result of sustained hypoxic stress might reflect a feedback mechanism to maintain peroxisome homeostasis.

值得注意的是,虽然细胞急性暴露于低氧条件下不会降低过氧化物酶体丰度[ 25 ],但通过关键调节因子的遗传失活来持续激活缺氧会显着减少过氧化物酶体的数量[ 33 ]。缺氧受缺氧诱导因子 (HIF) 家族转录因子的调节,这些转录因子在缺氧条件下具有活性,但在富氧条件下被 Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) 蛋白降解。激活的 HIF 转录重编程细胞以适应低氧张压环境[ 34 ]。有趣的是,VHL 敲除导致的 HIF2α的稳定促进了 pexophagage,导致过氧化物酶体丰度急剧降低[ 33 ]。对过氧化物酶体丰度相互影响的确切原因尚不清楚。然而,慢性缺氧已被证明可以防止急性缺氧的影响 [ 35 , 36 ]。因此,由于持续的缺氧应激而诱导 pexophagy 可能反映了维持过氧化物酶体稳态的反馈机制。

Peroxisomal regulation of lipid homeostasis during nutrient stress

营养胁迫期间脂质稳态的过氧化物酶体调节

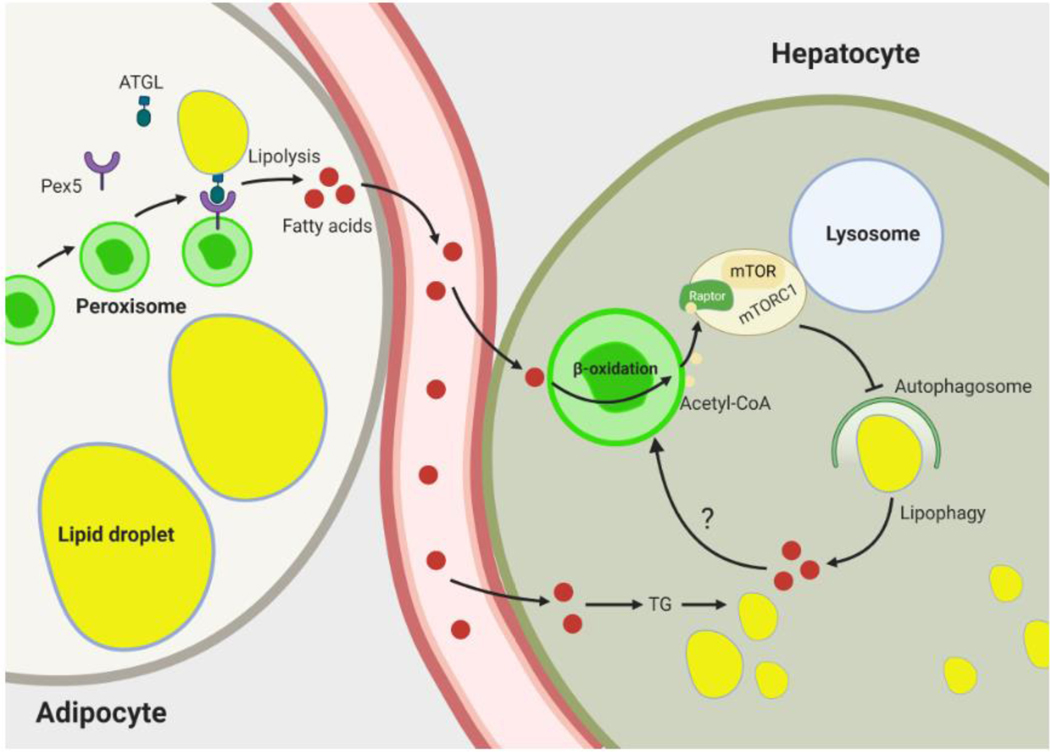

Adipose tissue stores excess energy as triglycerides within lipid droplets. This pool of intracellular lipid stores can be mobilized during nutrient deprivation through a process called lipolysis, which involves induction of β-adrenergic receptor signaling, resulting in the activation of a cAMP and protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent pathway [37]. Lipolysis is mediated by a series of lipases, including adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), an enzyme that catalyzes the first and rate-limiting step in the process, hydrolyzing triglycerides to diglycerides. Activities of lipolytic enzymes are regulated by nutritional status [37], but the mechanism through which these enzymes translocate onto lipid droplet and catalyze lipolysis remains ill-defined.

脂肪组织将多余的能量作为甘油三酯储存在脂滴中。在营养剥夺期间,这种细胞内脂质储存可以通过称为脂肪分解的过程进行调动,该过程涉及诱导β肾上腺素能受体信号传导,从而激活 cAMP 和蛋白激酶 A(PKA)依赖性途径[ 37 ]。脂肪分解由一系列脂肪酶介导,包括脂肪甘油三酯脂肪酶 (ATGL),这是一种催化过程中的第一步和限速步骤的酶,将甘油三酯水解为甘油二酯。脂肪分解酶的活性受营养状况的调节[ 37 ],但这些酶易位到脂滴上并催化脂肪分解的机制仍然不明确。

A recent study by Kong et al. [38] identified a role for peroxisomes in fasting-induced lipolysis in adipose tissue.Peroxisomes have long been known to associate with lipid droplets [39], but the physiological significance of this interaction has remained unclear. Kong et al. discovered that fasting stimulates physical interaction between peroxisomes and lipid droplets and induces fatty acid liberation via lipolysis in white adipose tissue (WAT) [38]. Similar results were observed in 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with isoproterenol, a β-adrenergic receptor agonist, to mimic the fasting response. Mechanistically, the authors demonstrated that fasting promotes interaction between peroxisomes and lipid droplets by increasing kinesin-like protein KIFC3-dependent movement of peroxisomes toward lipid droplets. Moreover, they reported that the peroxisomal biogenesis factor Pex5 interacts with ATGL and recruits it to peroxisome-lipid droplet contact sites in a manner dependent on PKA activation [38]. However, it is unclear how Pex5 interacts with ATGL since the lipolytic enzyme lacks a PTS1. It is also unclear what the fate is of the fatty acids liberated by peroxisome-mediated lipolysis.

Kong 等[ 38 ]最近的一项研究确定了过氧化物酶体在空腹诱导的脂肪组织脂肪分解中的作用。长期以来,人们一直知道过氧化物酶体与脂滴结合[ 39 ],但这种相互作用的生理意义仍不清楚。Kong 等发现,禁食会刺激过氧化物酶体和脂滴之间的物理相互作用,并通过脂肪分解在白色脂肪组织(white adiposition organization, WAT)中诱导脂肪酸释放[ 38 ]。在用异丙肾上腺素(一种β-肾上腺素能受体激动剂)处理的 3T3-L1 脂肪细胞中观察到类似的结果,以模拟禁食反应。从机制上讲,作者证明,禁食通过增加过氧化物酶体向脂滴的驱动蛋白样蛋白 KIFC3 依赖性运动来促进过氧化物酶体和脂滴之间的相互作用。此外,他们报告说,过氧化物酶体生物发生因子 Pex5 与 ATGL 相互作用,并以依赖于 PKA 激活的方式将其募集到过氧化物酶体-脂滴接触位点 [ 38 ]。然而,尚不清楚 Pex5 如何与 ATGL 相互作用,因为脂肪分解酶缺乏 PTS1。目前还不清楚过氧化物酶体介导的脂肪分解释放的脂肪酸的命运是什么。

Besides lipolysis, fatty acids could be liberated from triglycerides by lipophagy, a subtype of autophagy that involves encapsulation of lipid droplets within a double-membrane autophagosome, which fuses with a lysosome, followed by hydrolysis of triglycerides by lysosomal acid lipase A (LAL) [40]. Starvation activates the autophagy pathway, but paradoxically autophagic degradation of lipid droplets is normally not sufficient to prevent hepatic steatosis that results from prolonged nutrient deprivation. Acetyl-CoA is a key metabolic regulator of autophagy whose depletion is sufficient to promote autophagy activation, albeit through a previously undefined mechanism [41].

除脂肪分解外,脂肪酸还可以通过自噬从甘油三酯中释放出来, 脂肪自噬是自噬的一种亚型,涉及将脂滴包裹在双膜自噬体内,与溶酶体融合,然后通过溶酶体酸性脂肪酶 A(LAL) 40 水解甘油三酯[ ]。饥饿会激活自噬途径,但矛盾的是,脂滴的自噬降解通常不足以防止因长期营养剥夺而导致的肝脂肪变性。乙酰辅酶 A 是自噬的关键代谢调节剂,其消耗足以促进自噬激活,尽管是通过先前未定义的机制[ 41 ]。

Recent studies suggest that peroxisomal β-oxidation is a major source of cytosolic acetyl CoA that limits lipophagy activation in the liver under nutrient deprivation [42]. Hepatocyte-specific genetic inactivation of the peroxisomal β-oxidation enzyme Acox1 prevents against starvation-induced fatty liver in mice. Mechanistically, acetyl-CoA derived from Acox1-mediated fatty acid oxidation promotes acetylation of Raptor [42], a component of the mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase) complex 1 (mTORC1) [43]. This growth and metabolism regulatory complex senses nutrients and inhibits autophagy under nutrient sufficiency by phosphorylating various autophagy-related proteins, including ULK1 (Unc-51-like autophagy-activating kinase 1) [44], which promotes autophagy initiation and autophagosome formation. Raptor regulates subcellular localization of mTOR and promotes recruitment of its substrates [45]. As a consequence of hepatic Acox1 deficiency, lysosomal localization and activation of mTOR is impaired, resulting in decreased autophagy-inhibitory Ser757 phosphorylation of ULK1 and subsequent activation of lipophagy and protection against fatty liver [42]. The activation of mTORC1 was recently shown to also be impaired in peroxisome-deficient Chinese hamster ovary cells [46]. With regard to peroxisomal β-oxidation-mediated inhibition of mTORC1, these studies suggest a peroxisome-lysosome metabolic link restricts autophagic degradation of lipid droplets in the fasted state and controls hepatic lipid homeostasis. It is noteworthy that this is in contrast to the fasting-induced peroxisome-lipid droplet interaction discussed above, which enhances fatty acid liberation via the promotion of lipolysis in adipose tissue [38] (Figure 2). These opposing effects of peroxisomes on lipid hydrolysis suggest that peroxisomal processes are calibrated in a tissue-specific manner based on nutritional status. For example, fasting increases Acox1 gene expression in the liver but not in WAT [47].

最近的研究表明,过氧化物酶体β氧化是胞质乙酰辅酶 A 的主要来源,在营养剥夺下限制肝脏的噬脂激活[ 42 ]。过氧化物酶体β氧化酶 Acox1 的肝细胞特异性遗传失活可预防饥饿诱导的小鼠脂肪肝。从机制上讲,源自 Acox1 介导的脂肪酸氧化的乙酰辅酶 A 促进 Raptor[ 42 ]的乙酰化,Raptor 是 mTOR(雷帕霉素激酶机制靶标)复合物 1(mTORC1)的组分[ 43 ]。这种生长和代谢调节复合物通过磷酸化各种自噬相关蛋白(包括 ULK1(Unc-51 样自噬激活激酶 1)[ 44 ]来感知营养物质并在营养充足的情况下抑制自噬,从而促进自噬启动和自噬体形成。Raptor 调节 mTOR 的亚细胞定位并促进其底物的募集 [ 45 ]。由于肝脏 Acox1 缺乏,溶酶体定位和 mTOR 的激活受损,导致 ULK1 的自噬抑制性 Ser757 磷酸化减少,随后激活噬脂作用并预防脂肪肝 [ 42 ]。最近显示,过氧化物酶体缺陷的中国仓鼠卵巢细胞中 mTORC1 的激活也受损[ 46 ]。关于过氧化物酶体β氧化介导的 mTORC1 抑制,这些研究表明过氧化物酶体-溶酶体代谢联系限制了禁食状态下脂滴的自噬降解并控制肝脂稳态。 值得注意的是,这与上面讨论的空腹诱导的过氧化物酶体-脂滴相互作用形成鲜明对比,后者通过促进脂肪组织中的脂肪分解来增强脂肪酸游离 [ 38 ] ( Figure 2 )。过氧化物酶体对脂质水解的这些相反作用表明,过氧化物酶体过程是根据营养状况以组织特异性方式校准的。例如,禁食会增加肝脏中 Acox1 基因的表达,但不会增加 WAT 中的 Acox1 基因表达[ 47 ]。

Figure 2. Role of peroxisomes in nutrient deprivation-induced lipid hydrolysis.

图 2.过氧化物酶体在营养剥夺诱导的脂质水解中的作用。

In adipocytes, fasting stimulates interaction between peroxisomes and lipid droplets (LD) by increasing kinesin-like protein KIFC3-dependent movement of peroxisomes toward LDs. The peroxisomal biogenesis factor Pex5 interacts with ATGL and recruits it to peroxisome-LD contact sites to induce lipolysis. The fatty acids liberated from hydrolysis of LDs are mobilized and taken up by peripheral tissues, such as the liver. In hepatocytes, these fatty acids are reesterified to triglyceride and stored in lipid droplets. Peroxisomes inhibit hydrolysis of these lipids by blocking lipophagy. This involves peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation-mediated production of acetyl-CoA, which promotes acetylation of Raptor, a component of mTORC1. Activated mTORC1 inhibits lipophagy. Fatty acids released by lipophagic hydrolysis of triglycerides may also be oxidized in peroxisomes to generate acetyl-CoA, potentially reflecting a negative feedback mechanism to limit hydrolysis of intracellular lipid stores. Abbreviations: ATGL, adipose triglyceride lipase; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; mTORC1, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1; TG, triglyceride.

在脂肪细胞中,禁食通过增加过氧化物酶体向 LD 的驱动蛋白样蛋白 KIFC3 依赖性运动来刺激过氧化物酶体和脂滴 (LD) 之间的相互作用。过氧化物酶体生物发生因子 Pex5 与 ATGL 相互作用,并将其募集到过氧化物酶体-LD 接触位点以诱导脂肪分解。从 LD 水解中释放出来的脂肪酸被外周组织(例如肝脏)动员并吸收。在肝细胞中,这些脂肪酸被再酯化为甘油三酯并储存在脂滴中。过氧化物酶体通过阻断噬脂作用来抑制这些脂质的水解。这涉及过氧化物酶体脂肪酸氧化介导的乙酰辅酶 A 的产生,乙酰辅酶 A 促进猛禽(mTORC1 的一种成分)的乙酰化。激活的 mTORC1 抑制噬脂作用。甘油三酯的食脂水解释放的脂肪酸也可能在过氧化物酶体中被氧化生成乙酰辅酶 A,这可能反映了限制细胞内脂质储存水解的负反馈机制。缩写:ATGL,脂肪甘油三酯脂肪酶;mTOR,雷帕霉素的机制靶点;mTORC1,雷帕霉素复合物 1 的机制靶标;TG,甘油三酯。

Role of peroxisomes in environmental stress

过氧化物酶体在环境胁迫中的作用

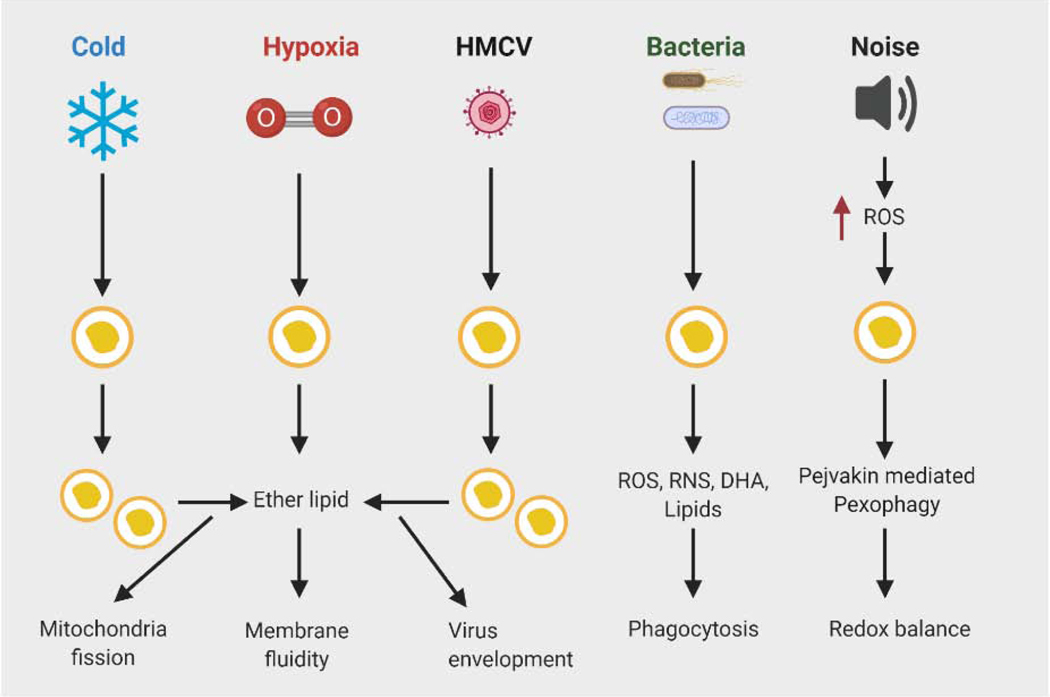

In addition to metabolic stress, peroxisomes play a critical role in adaptation to environmental stress. In this section, we discuss the role of peroxisomes in brown fat-mediated thermogenesis in response to cold, how these organelles are involved in protection against noise-induced hearing loss caused by oxidative stress, and how they regulate innate immune response to infectious agents (Figure 3).

除了代谢应激外,过氧化物酶体在适应环境应激方面也起着至关重要的作用。在本节中,我们讨论过氧化物酶体在棕色脂肪介导的产热反应中的作用,这些细胞器如何参与防止氧化应激引起的噪声引起的听力损失,以及它们如何调节对传染源的先天免疫反应 ( Figure 3 )。

Figure 3. Role of peroxisomes in response to various stressors.

图 3.过氧化物酶体在应对各种压力源中的作用。

Cold induces peroxisomal biogenesis in brown fat results in increased production of plasmalogens, a form of ether lipids that are a component of mitochondrial membranes. Plasmalogens promote cold-induced mitochondrial fission to support thermogenesis. Hypoxic stress also promotes synthesis of ether lipids, which help to reduce membrane rigidity associated with low oxygen tension and improve cellular fitness. Peroxisomes are involved in innate immune response to viral infections, but some viruses have evolved a strategy to escape the antiviral effect mediated by peroxisomes. Viruses, such as HMCV promote peroxisomal production of ether lipids to support secondary envelopment of infectious particles. Peroxisomes play a protective role in bacterial infections through requirement of peroxisomal ROS and lipid metabolism in phagocytosis. Noise promotes ROS production and oxidative damage, leading to auditory hair cell damage and hearing loss. Pejvakin mediated-pexophagy is activated by noise-induced ROS in auditory hair cells to clear damaged peroxisomes, paving the way for peroxisome biogenesis. Pejvakin deficiency leads to noise-induced hearing loss. Abbreviations: DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; HMCV, human cytomegalovirus; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

寒冷诱导棕色脂肪中的过氧化物酶体生物发生导致缩醛磷脂的产生增加,缩醛磷脂是线粒体膜的一种组成部分。疟原蛋白促进冷诱导的线粒体裂变以支持产热。缺氧应激还促进乙醚脂质的合成,有助于降低与低氧压相关的膜刚性并改善细胞健康。过氧化物酶体参与对病毒感染的先天免疫反应,但一些病毒已经进化出一种策略来逃避过氧化物酶体介导的抗病毒作用。HMCV 等病毒促进醚脂的过氧化物酶体产生,以支持感染性颗粒的二次包膜。过氧化物酶体通过吞噬作用中过氧化物酶体 ROS 和脂质代谢的需求,在细菌感染中发挥保护作用。噪音会促进 ROS 的产生和氧化损伤,导致听觉毛细胞损伤和听力损失。Pejvakin 介导的 pexophagy 被听觉毛细胞中噪声诱导的 ROS 激活,以清除受损的过氧化物酶体,为过氧化物酶体的生物发生铺平道路。Pejvakin 缺乏会导致噪声引起的听力损失。缩写:DHA,二十二碳六烯酸;HMCV,人巨细胞病毒;RNS,活性氮种类;ROS,活性氧。

Peroxisome-derived lipids and the regulation of thermogenesis in response to cold exposure

过氧化物酶体衍生的脂质和响应冷暴露的产热调节

One of the challenges for euthermic animals is to maintain their body temperature in a cold environment. Cold-induced heat production in mammals occurs through skeletal muscle shivering [48] or by non-shivering thermogenesis, which is mediated primarily by brown adipose tissue (BAT) and the related beige adipocytes that appear within subcutaneous WAT in response to prolonged cold exposure or β-adrenergic stimulation [49]. Brown and beige fat cells are enriched in mitochondria and specialize in oxidizing fatty acids and glucose to generate heat via mitochondrial uncoupling. In addition to promoting thermogenesis through uncoupled respiration, mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles that regulate the thermogenic capacity of adipocytes through their ability to undergo fission in response to β-adrenergic stimulation. Fragmented and circular mitochondria are thought to exhibit increased uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation by directing nutrient oxidation toward heat production instead of ATP synthesis [50].

真热动物面临的挑战之一是在寒冷的环境中保持体温。哺乳动物的冷诱发热量产生是通过骨骼肌颤抖[ 48 ]或非颤抖产热发生的,这主要由棕色脂肪组织(brown adiposition organization, BAT)和皮下 WAT 内出现的相关米色脂肪细胞介导,以响应长时间的寒冷暴露或β肾上腺素能刺激 49 [ ]。棕色和米色脂肪细胞富含线粒体,专门氧化脂肪酸和葡萄糖,通过线粒体解偶联产生热量。除了通过非偶联呼吸促进产热外,线粒体还是高度动态的细胞器,通过脂肪细胞响应β肾上腺素能刺激而发生裂变的能力来调节脂肪细胞的产热能力。碎片化和环状线粒体被认为通过将营养物质氧化引导至热量产生而不是 ATP 合成,表现出氧化磷酸化解偶联的增加 [ 50 ]。

Peroxisomes are also a dynamic organelle whose abundance in brown adipocytes increases with cold exposure [51, 52]. Recent studies indicate that cold-induced peroxisomal biogenesis is mediated by the thermogenic transcriptional co-regulator PRDM16 [53], suggesting that the transcriptional regulation of thermogenesis and de novo peroxisome formation is linked. Consistent with a role for peroxisomes in thermogenesis, disruption of peroxisomal biogenesis through adipose-specific knockout of the critical peroxisomal biogenesis factor Pex16 results in cold intolerance in mice due to inhibition of cold-induced mitochondrial fission. Mechanistically, the loss of peroxisomes decreases the mitochondrial membrane content of plasmalogens. Treatment of mice with alkyl glycerol, a plasmalogen precursor, restores cold-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and thermogenesis in Pex16 knockout mice, suggesting that peroxisomes channel lipids to mitochondria in brown and beige adipocytes to regulate mitochondrial dynamics and thermogenesis [53]. Future research will be required to understand the precise mechanism through which plasmalogens affect mitochondrial fission. One potential explanation is that these peroxisome-derived lipids are required to maintain mitochondrial membrane fluidity necessary for cold-induced mitochondrial fission. It is also possible that plasmalogens assist in the recruitment of factors involved in mitochondrial dynamics.

过氧化物酶体也是一种动态细胞器,其棕色脂肪细胞中的丰度随着寒冷暴露而增加 [ 51 , 52 ]。最近的研究表明,冷诱导的过氧化物酶体生物发生是由产热转录共调节因子 PRDM16 介导的[ 53 ],这表明产热的转录调节与从头过氧化物酶体形成有关。与过氧化物酶体在产热中的作用一致,通过脂肪特异性敲除关键的过氧化物酶体生物发生因子 Pex16 破坏过氧化物酶体生物发生,由于抑制冷诱导的线粒体裂变,导致小鼠不耐寒。从机制上讲,过氧化物酶体的丢失会降低缩醛磷脂的线粒体膜含量。用烷基甘油(一种缩醛磷前体)处理小鼠可恢复 Pex16 基因敲除小鼠中冷诱导的线粒体片段化和产热,这表明过氧化物酶体将脂质引导到棕色和米色脂肪细胞中的线粒体以调节线粒体动力学和产热 [ 53 ]。未来的研究将需要了解等离子体影响线粒体裂变的精确机制。一种可能的解释是,这些过氧化物酶体衍生的脂质是维持冷诱导线粒体裂变所必需的线粒体膜流动性所必需的。缩醛磷脂也有可能有助于招募参与线粒体动力学的因子。

Peroxisomal regulation of noise-induced hearing loss

过氧化物酶体调节噪声性听力损失

In the modern industrial society, noise is another major environmental stressor. Overexposure to noise promotes ROS production and oxidative damage, leading to auditory hair cell damage and hearing loss [54, 55], while antioxidant therapy has been shown to prevent hearing loss in mice [56]. Consistent with the important role of peroxisomes in ROS metabolism, polymorphisms in the peroxisomal antioxidant enzyme catalase are associated with noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) in humans [57]. The initial evidence for a direct role of peroxisomes in NIHL was provided by the discovery that Pejvakin (also called DFNB59), a poorly characterized protein genetically linked to sensorineural hearing loss, is associated with peroxisomes, particularly with peroxisomal protrusions and “string-of-beads” structures indicative of peroxisome growth and fission [55]. Like humans with mutations in the gene encoding Pejvakin (PVJK), Pejvakin-deficient mice are hypervulnerable to noise. Embryonic fibroblasts from Pjvk+/+ mice stressed with H2O2 show a significant increase in peroxisome number, but those from Pjvk−/− mice remain unchanged. Furthermore, Pjvk−/− mice only display structural peroxisome abnormalities in hair cells after hearing loss onset due to the oxidative stress caused by noise exposure [55].

在现代工业社会中,噪音是另一个主要的环境压力源。过度暴露于噪音会促进 ROS 的产生和氧化损伤,导致听觉毛细胞损伤和听力损失 [ 54 , 55 ],而抗氧化疗法已被证明可以预防小鼠听力损失 [ 56 ]。与过氧化物酶体在 ROS 代谢中的重要作用一致,过氧化物酶体抗氧化酶过氧化氢酶的多态性与人类噪声性听力损失(noise-induced hearing loss, NIHL)有关[ 57 ]。过氧化物酶体在 NIHL 中直接作用的初步证据是发现 Pejvakin(也称为 DFNB59)是一种与感音神经性听力损失有遗传联系的特征不佳的蛋白质,与过氧化物酶体有关,特别是与过氧化物酶体突起和指示过氧化物酶体生长和裂变的“串珠”结构有关 [ 55 ].与编码 Pejvakin (PVJK) 基因突变的人类一样,Pejvakin 缺陷小鼠对噪音非常敏感。用 H2O2 胁迫的 Pjvk + / + 小鼠的胚胎成纤维细胞显示出过氧化物酶体数量的显着增加,但来自 Pjvk−/- 小鼠的胚胎成纤维细胞保持不变。此外,由于噪声暴露引起的氧化应激,Pjvk−/− 小鼠在听力损失发作后仅在毛细胞中表现出结构性过氧化物酶体异常[ 55 ]。

Additional mechanistic studies suggest that following sound-induced oxidative stress, auditory cells undergo autophagic degradation of damaged peroxisomes through pexophagy prior to peroxisome proliferation. Pejvakin contains a functional LC3-interacting region (LIR) and directly recruits the autophagosomal marker LC3B to peroxisomes in response to H2O2 treatment in HepG2 cells to facilitate pexophagy and pave the way for peroxisome proliferation [58]. Taken together, these studies establish a key pathway in which pejvakin-mediated peroxisome degradation and proliferation protect auditory hair cells against noise-induced oxidative stress and reveal that the DFNB59 form of deafness is a pexophagy disorder. As discussed above, activation of pexophagy involves Pex5-dependent peroxisomal recruitment of the ATM kinase [20]. It is unclear whether inactivation of PVJK disrupts the Pex5/ATM axis. Nevertheless, this work opens up new therapeutic avenues as antioxidant supplementation and AAV-mediated gene therapy appear to be effective treatments for the disease [55].

其他机制研究表明,在声音诱导的氧化应激之后,听觉细胞在过氧化物酶体增殖之前通过异食对受损的过氧化物酶体进行自噬降解。Pejvakin 含有功能性 LC3 相互作用区(LIR),并直接将自噬体标志物 LC3B 募集到过氧化物酶体中,以响应 HepG2 细胞中的 H2O2 处理,以促进 pexophagage 并为过氧化物酶体增殖铺平道路[ 58 ]。总之,这些研究建立了一条关键途径,其中 pejvakin 介导的过氧化物酶体降解和增殖保护听觉毛细胞免受噪音诱导的氧化应激,并揭示 DFNB59 形式的耳聋是一种吞噬障碍。如上所述,pexophagage 的激活涉及 ATM 激酶的 Pex5 依赖性过氧化物酶体募集 [ 20 ]。目前尚不清楚 PVJK 的失活是否会破坏 Pex5/ATM 轴。然而,这项工作开辟了新的治疗途径,因为抗氧化剂补充剂和 AAV 介导的基因疗法似乎是治疗该疾病的有效方法 [ 55 ]。

Role of peroxisomes in innate immune response to viral and bacterial infections

过氧化物酶体在病毒和细菌感染的先天免疫反应中的作用

Besides extreme physical environment, pathogens, such as viruses and bacteria also contribute to environmental stress in animals. Innate immune system is the first line of defense against infections. For viral infections, the innate immune response involves recognition of viral nucleic acids by pathogen recognition receptors, including cytosolic receptors such as RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) that activate mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) to destroy viruses [59]. Although originally identified as a mitochondrial membrane protein that activates NF-kB and interferon regulatory factors, resulting in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and type I interferons (IFN), MAVS is also located at the peroxisomal membrane and triggers expression of type III IFN and IFN-stimulated genes upon viral infections [60]. The products of IFN-stimulated genes have antiviral effects, which destroy the virus or inhibit viral replication [61]. However, some viruses have evolved a strategy to escape the antiviral effect mediated by peroxisomes. For instance, the flavivirus capsid protein promotes sequestration and degradation of Pex19, a cytoplasmic chaperone of peroxisomal membrane proteins, leading to reduction of peroxisome number and impairment of early antiviral signaling [62]. Recent studies suggest that enveloped viruses, such as human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) do not inhibit peroxisomal biogenesis, but rather increase it to support their replication [63]. The authors suggest that this leads to increased production of plasmalogens necessary for secondary envelopment and the assembly of infectious particles. However, since peroxisomal lipid synthesis also contributes to the production of conventional diacyl phospholipids [64], additional work is required to determine if plasmalogens are directly necessary for envelopment.

除了极端的物理环境外,病毒和细菌等病原体也会导致动物的环境压力。先天免疫系统是抵御感染的第一道防线。对于病毒感染,先天免疫应答涉及病原体识别受体对病毒核酸的识别,包括细胞质受体,如 RIG-I 样受体(RLR),可激活线粒体抗病毒信号蛋白(mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein, MAVS)以破坏病毒[ 59 ]。虽然 MAVS 最初被鉴定为一种线粒体膜蛋白,可激活 NF-kB 和干扰素调节因子,从而产生促炎细胞因子和 I 型干扰素(IFN),但 MAVS 也位于过氧化物酶体膜上,并在病毒感染时触发 III 型干扰素和 IFN 刺激基因的表达[ 60 ]。IFN 刺激基因的产物具有抗病毒作用,可破坏病毒或抑制病毒复制[ 61 ]。然而,一些病毒已经进化出一种策略来逃避过氧化物酶体介导的抗病毒作用。例如,黄病毒衣壳蛋白促进过氧化物酶体膜蛋白的细胞质伴侣 Pex19 的螯合和降解,导致过氧化物酶体数量减少和早期抗病毒信号传导受损[ 62 ]。最近的研究表明,包膜病毒,如人类巨细胞病毒(human cytomegalovirus, HCMV)和单纯疱疹病毒 1 型(herpes simplex virus type 1, HSV-1)不会抑制过氧化物酶体生物发生,而是会增加过氧化物酶体的生物发生以支持其复制[ 63 ]。作者认为,这导致二次包膜和传染性颗粒组装所必需的缩醛磷脂的产生增加。 然而,由于过氧化物酶体脂质的合成也有助于产生常规的二酰磷脂[ 64 ],因此需要额外的工作来确定缩醛磷脂是否直接需要包膜。

The peroxisomal role in innate immune response is not limited to only viral infections, but extends to bacterial infections as well. Microbial invaders are destroyed through phagocytosis, in which specialized cells use plasma membrane to engulf pathogens, giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. The phagosome fuses with lysosome, forming a phagolysosome, which degrades pathogens [65]. A study by Di Cara et al. has identified a role for peroxisomes in phagocytosis [66]. Peroxisomes are localized to the sites of phagosome formation in Drosophila S2 cells and knockdown of Pex5 or Pex7 results in reduced bacterial uptake via phagocytosis. Peroxisome deficiency leads to disorganization of the actin network and a defect in phagocytic cup formation, coupled with impaired ROS metabolism. Overexpression of catalase in peroxisome deficient cells or treatment with phosphatidylinositols and DHA, lipids thought to be produced in peroxisomes, rescues phagocytosis [66]. These studies suggest that peroxisomal function in ROS and lipid metabolism is important for phagocytosis, but the detailed molecular mechanism remains to be discovered. Peroxisomal lipid metabolism has also been implicated in bactericidal activity through a different mechanism involving FAMIN, a laccase domain-containing protein that partially localizes to the cytosolic surface of peroxisomes through its interaction with fatty acid synthase. FAMIN regulates β-oxidation of de novo synthesized fatty acids. FAMIN-deficient macrophages have impaired mitochondrial ROS production, a defect in inflammasome activation and reduced bacterial clearance [67].

过氧化物酶体在先天免疫反应中的作用不仅限于病毒感染,还延伸到细菌感染。微生物入侵者通过吞噬作用被消灭,其中特化细胞利用质膜吞噬病原体,产生一个称为吞噬体的内部隔室。吞噬体与溶酶体融合,形成吞噬溶酶体,降解病原体 [ 65 ]。Di Cara 等人的一项研究已经确定了过氧化物酶体在吞噬作用中的作用[ 66 ]。过氧化物酶体定位于果蝇 S2 细胞中吞噬体形成的位点,敲低 Pex5 或 Pex7 导致通过吞噬作用减少细菌摄取。过氧化物酶体缺乏会导致肌动蛋白网络紊乱和吞噬杯形成缺陷,以及 ROS 代谢受损。过氧化物酶体缺陷细胞中过氧化氢酶的过度表达或用磷脂酰肌醇和 DHA(被认为是在过氧化物酶体中产生的脂质)处理,可以挽救吞噬作用 [ 66 ]。这些研究表明,ROS 和脂质代谢中的过氧化物酶体功能对吞噬作用很重要,但详细的分子机制仍有待发现。过氧化物酶体脂质代谢也通过涉及 FAMIN 的不同机制与杀菌活性有关,FAMIN 是一种含有漆酶结构域的蛋白质,通过与脂肪酸合酶的相互作用部分定位到过氧化物酶体的胞质表面。FAMIN 调节从头合成脂肪酸的β氧化。FAMIN 缺陷巨噬细胞会损害线粒体 ROS 的产生,这是炎症小体激活的缺陷和细菌清除率降低[ 67 ]。

Concluding Remarks 结束语

Peroxisomes participate in a variety of metabolic functions. The physiological significance of these processes is only now beginning to be understood. It is becoming increasingly clear that peroxisomes are a critical signaling node that communicates with other organelles and responds to various types of cellular stress. While the role of peroxisomes in mediating and regulating redox-driven signaling events is well-appreciated, emerging evidence suggests that other products of peroxisomal metabolism, including acetyl-CoA and ether lipids, also affect cellular signaling related to stress. In the context of nutrient stress, peroxisomal β-oxidation is a major source of cytosolic acetyl CoA that controls hepatic lipid hydrolysis. Although peroxisomal β-oxidation is required for catabolism of VLCFAs, the dramatic decrease in the liver acetyl-CoA content due to hepatic Acox1 deficiency [42] suggests that the peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway might possess a broader fatty acid substrate specificity. It is also possible that fatty acids released by hepatic lipophagy are oxidized in peroxisomes to generate acetyl-CoA, potentially reflecting a negative feedback mechanism. Additional work is required to explore these possibilities (see Outstanding Questions). Future research will also be necessary to understand the molecular mechanisms through which peroxisomal lipids promote cellular fitness during hypoxic stress, control mitochondrial dynamics during cold to promote thermogenesis, and regulate innate immune responses to infectious agents, and to determine whether these peroxisomal functions could be targeted to treat human diseases. For example, it would be of great interest to determine if the immunometabolism-regulatory function of peroxisomes could be leveraged to treat obesity-associated inflammation. Regulation of cellular stress by peroxisomes is a fertile area of research. A better understanding of how these versatile organelles control stress responses could reveal new strategies to treat disease.

过氧化物酶体参与多种代谢功能。这些过程的生理意义现在才开始被理解。越来越明显的是,过氧化物酶体是与其他细胞器通信并对各种类型的细胞应激做出反应的关键信号节点。虽然过氧化物酶体在介导和调节氧化还原驱动的信号事件中的作用已得到广泛认可,但新出现的证据表明,过氧化物酶体代谢的其他产物,包括乙酰辅酶 A 和醚脂,也会影响与压力相关的细胞信号传导。在营养胁迫的背景下,过氧化物酶体β氧化是控制肝脂水解的胞质乙酰辅酶 A 的主要来源。尽管过氧化物酶体β氧化是 VLCFAs 分解代谢所必需的,但由于肝脏 Acox1 缺乏导致肝脏乙酰辅酶 A 含量急剧下降[ 42 ]表明过氧化物酶体β氧化途径可能具有更广泛的脂肪酸底物特异性。肝噬脂释放的脂肪酸也有可能在过氧化物酶体中被氧化生成乙酰辅酶 A,这可能反映了负反馈机制。探索这些可能性需要额外的工作(参见 Outstanding Questions )。未来的研究还需要了解过氧化物酶体脂质在缺氧应激期间促进细胞适应性、在寒冷期间控制线粒体动力学以促进产热以及调节对传染源的先天免疫反应的分子机制,并确定这些过氧化物酶体功能是否可以靶向治疗人类疾病。 例如,确定过氧化物酶体的免疫代谢调节功能是否可以用于治疗肥胖相关炎症将非常有趣。过氧化物酶体调节细胞应激是一个肥沃的研究领域。更好地了解这些多功能细胞器如何控制应激反应可能会揭示治疗疾病的新策略。

Outstanding Questions. 未决问题。

Could the role of peroxisomes in stress response be leveraged for treatment of human diseases, such as obesity, diabetes and cancer?

过氧化物酶体在应激反应中的作用是否可以用于治疗肥胖、糖尿病和癌症等人类疾病?

How is peroxisome-derived acetyl-CoA channeled toward Raptor acetylation? Are peroxisome-lysosome membrane contacts involved in this process? What other proteins are acetylated by this pool of acetyl-CoA?

过氧化物酶体衍生的乙酰辅酶 A 如何引导到 Raptor 乙酰化?过氧化物酶体-溶酶体膜接触是否参与了这个过程?还有哪些其他蛋白质被乙酰辅酶 A 池乙酰化?

As a redox-sensitive protein, does Pex5 directly regulate ROS-activated pexophagy independently of ATM?

作为一种氧化还原敏感蛋白,Pex5 是否独立于 ATM 直接调节 ROS 激活的 pexophagage?

What is the molecular basis of peroxisome-mediated regulation of mitochondrial fission?

过氧化物酶体介导的线粒体裂变调节的分子基础是什么?

What is the molecular mechanism of Pejvakin mediated pexophagy? Is Pejvakin an adaptor protein selectively involved in pexophagy? Is the role of Pejvakin in pexophagy specific to auditory hair cells?

Pejvakin 介导的 pexophagage 的分子机制是什么?Pejvakin 是一种选择性参与 pexophagage 的衔接蛋白吗?Pejvakin 在吞噬中的作用是否特定于听觉毛细胞?

Highlights. 突出。

Peroxisomes are not only passive performers of various metabolic reactions, but also a critical signaling hub that integrates signals originating from these reactions and communicates with other organelles to respond to various stressors, including oxidative stress, hypoxia, starvation, cold, noise and pathogens.

过氧化物酶体不仅是各种代谢反应的被动执行者,而且是一个关键的信号枢纽,它整合了来自这些反应的信号,并与其他细胞器通信以应对各种压力源,包括氧化应激、缺氧、饥饿、寒冷、噪音和病原体。Although peroxisome-derived ROS play a key role in cellular signaling related to stress, recent studies suggest that other products of peroxisomal metabolism, such as acetyl-CoA and ether lipids, are also important for metabolic adaptation to stress.

尽管过氧化物酶体衍生的 ROS 在与压力相关的细胞信号传导中起着关键作用,但最近的研究表明,过氧化物酶体代谢的其他产物,如乙酰辅酶酶 A 和醚脂,对于代谢适应压力也很重要。Peroxisomes control lipid hydrolysis and mobilization during nutrient deprivation through their ability to engage in crosstalk with other organelles and generate signaling metabolites, such as acetyl-CoA.

过氧化物酶体通过与其他细胞器发生串扰并产生信号代谢物(例如乙酰辅酶 A)的能力来控制营养剥夺期间的脂质水解和动员。Peroxisome-derived lipids promote cellular fitness during hypoxic stress, regulate mitochondrial dynamics to support cold-induced thermogenesis, and control innate immune responses to infectious pathogens.

过氧化物酶体衍生的脂质在缺氧应激期间促进细胞健康,调节线粒体动力学以支持冷诱导的产热,并控制对传染性病原体的先天免疫反应。

Acknowledgements 确认

This work was supported by NIH grants DK115867, DK118333, and DK020579.

这项工作得到了 NIH 拨款 DK115867、DK118333 和 DK020579 的支持。

Glossary 词汇表

- β-oxidation β氧化

process of fatty acid catabolism, in which two carbons are sequentially removed from the carboxyl terminus of a fatty acyl CoA molecule. The process is named as such because the beta carbon of the fatty acid undergoes oxidation

脂肪酸分解代谢过程,其中两个碳从脂肪酰基辅酶 A 分子的羧基末端依次去除。该过程之所以如此命名,是因为脂肪酸的β碳发生氧化- Ether lipid 醚脂

peroxisome-derived glycerophospholipids in which the hydrocarbon chain at the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone is attached by an ether bond, as opposed to an ester bond in the more common diacyl phospholipids

过氧化物酶体衍生的甘油磷脂,其中甘油主链 sn-1 位置的碳氢化合物链通过醚键连接,而不是更常见的二酰磷脂中的酯键- Ferroptosis 铁死亡

an iron-dependent cell death process that is distinct from apoptosis

不同于细胞凋亡的铁依赖性细胞死亡过程- HepG2 cells HepG2 细胞

a cell line derived from a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma

源自肝细胞癌患者的细胞系- Lipolysis 脂解

a cytosolic process through which triglycerides stored in lipid droplets are hydrolyzed, generating free fatty acids and glycerol

储存在脂滴中的甘油三酯被水解,产生游离脂肪酸和甘油的胞质过程- Pexophagy

selective autophagy of peroxisomes, which involves degradation of peroxisomes through formation of a double membrane structure called autophagosome around the peroxisomal cargo, which then fuses with lysosomes

过氧化物酶体的选择性自噬,涉及通过在过氧化物酶体货物周围形成称为自噬体的双膜结构来降解过氧化物酶体,然后与溶酶体融合- Plasmalogen 等离子磷脂

ether lipid characterized by a vinyl ether linkage at the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone

醚脂的特征是甘油主链的 SN-1 位置的乙烯基醚键- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

活性氧 (ROS) molecules containing a partially reduced form of oxygen that are unstable and chemically reactive

含有部分还原形式的氧的分子,不稳定且具有化学反应性- Saturated fatty acid 饱和脂肪酸

lipid molecule consisting of a long chain of hydrocarbons to which a terminal carboxyl group is attached. They are named as such because they are saturated with hydrogens since neighboring carbons in the hydrocarbon chain are only linked by single bonds, which increases the number of hydrogens on each carbon

脂质分子由长链碳氢化合物组成,末端羧基连接到其上。它们之所以如此命名,是因为它们富含氢,因为碳氢化合物链中的相邻碳仅通过单键连接,这增加了每个碳上的氢数量- Unsaturated fatty acid 不饱和脂肪酸

fatty acid that has one or more carbon-carbon double bonds

具有一个或多个碳-碳双键的脂肪酸

Footnotes 脚注

Declaration of Interests

利益声明

The authors declare no competing interests.

作者声明没有利益冲突。

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

出版商免责声明: 这是一份未经编辑的手稿的 PDF 文件,已被接受出版。作为对客户的服务,我们提供了手稿的早期版本。手稿在以最终形式发表之前将对最终校样进行文案编辑、排版和审查。请注意,在制作过程中可能会发现可能影响内容的错误,并且适用于期刊的所有法律免责声明都与此相关。

References 引用

-

1.Lodhi IJ and Semenkovich CF (2014) Peroxisomes: a nexus for lipid metabolism and cellular signaling. Cell Metab

19 (3), 380–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1.Lodhi IJ 和 Semenkovich CF (2014) 过氧化物酶体:脂质代谢和细胞信号传导的联系。细胞代谢 19 (3), 380–92。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

2.Mahalingam SS

et al. (2020) Balancing the Opposing Principles That Govern Peroxisome Homeostasis. Trends Biochem Sci. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2.Mahalingam SS 等人(2020 年)平衡控制过氧化物酶体稳态的对立原则。趋势 生化科学 doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2020.09.006.[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

3.Huybrechts SJ

et al. (2009) Peroxisome dynamics in cultured mammalian cells. Traffic

10 (11), 1722–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3.Huybrechts SJ 等人 (2009) 培养哺乳动物细胞中的过氧化物酶体动力学。交通 10 (11), 1722–33。[ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

4.Chu BB

et al. (2015) Cholesterol transport through lysosome-peroxisome membrane contacts. Cell

161 (2), 291–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4.Chu BB 等人 (2015) 通过溶酶体-过氧化物酶体膜接触转运胆固醇。细胞 161 (2), 291–306。[ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

5.Chrousos GP (2009) Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat Rev Endocrinol

5 (7), 374–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5.Chrousos GP (2009) 压力和压力系统的障碍。国家内分泌牧师 5 (7), 374–81。[ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

6.Boveris A. et al. (1972) The cellular production of hydrogen peroxide. Biochem J

128 (3), 617–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6.Boveris, A. et al. (1972) 过氧化氢的细胞产生。生物化学杂志 128 (3), 617–30。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

7.Cipolla CM and Lodhi IJ (2017) Peroxisomal Dysfunction in Age-Related Diseases. Trends Endocrinol Metab

28 (4), 297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7.Cipolla CM 和 Lodhi IJ (2017) 与年龄相关的疾病中的过氧化物酶体功能障碍。趋势内分泌代谢 28 (4), 297–308。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

8.Finkel T. (2011) Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species. J Cell Biol

194 (1), 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8.Finkel T. (2011) 活性氧的信号转导。细胞生物学杂志 194 (1), 7–15。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

9.Fransen M. and Lismont C. (2019) Redox Signaling from and to Peroxisomes: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. Antioxid Redox Signal

30 (1), 95–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9.Fransen M. 和 Lismont C. (2019) 来自过氧化物酶体和过氧化物酶体的氧化还原信号传导:进展、挑战和前景。抗氧化氧化还原信号 30 (1), 95–112。[ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

10.Chung HL

et al. (2020) Loss- or Gain-of-Function Mutations in ACOX1 Cause Axonal Loss via Different Mechanisms. Neuron

106 (4), 589–606

e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10.Chung HL 等人 (2020) ACOX1 中的功能丧失或获得突变通过不同的机制导致轴突丢失。神经元 106 (4), 589–606 e6。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

11.Chen XF

et al. (2018) SIRT5 inhibits peroxisomal ACOX1 to prevent oxidative damage and is downregulated in liver cancer. EMBO Rep

19 (5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11.Chen XF 等人 (2018) SIRT5 抑制过氧化物酶体 ACOX1 以防止氧化损伤,并在肝癌中下调。EMBO 代表 19 (5)。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

12.Matsushita N. et al. (2011) Distinct regulation of mitochondrial localization and stability of two human Sirt5 isoforms. Genes Cells

16 (2), 190–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12.Matsushita N. et al. (2011) 两种人 Sirt5 亚型线粒体定位和稳定性的不同调节。基因细胞 16 (2), 190–202。[ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

13.Dubreuil MM

et al. (2020) Systematic Identification of Regulators of Oxidative Stress Reveals Non-canonical Roles for Peroxisomal Import and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway. Cell Rep

30 (5), 1417–1433

e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13.Dubreuil MM 等人(2020 年)氧化应激调节因子的系统鉴定揭示了过氧化物酶体输入和磷酸戊糖途径的非典型作用。细胞代表 30 (5), 1417–1433 e7。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

14.Gould SG

et al. (1987) Identification of a peroxisomal targeting signal at the carboxy terminus of firefly luciferase. J Cell Biol

105 (6 Pt 2), 2923–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14.Gould SG 等人(1987)在萤火虫荧光素酶羧基末端的过氧化物酶体靶向信号的鉴定。细胞生物学杂志 105(6 第 2 部分),2923-31。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

15.Okumoto K. et al. (2020) The peroxisome counteracts oxidative stresses by suppressing catalase import via Pex14 phosphorylation. Elife

9. doi: 10.7554/eLife.55896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15.Okumoto K. et al. (2020) 过氧化物酶体通过 Pex14 磷酸化抑制过氧化氢酶输入来抵消氧化应激。生活 9.doi:10.7554/eLife.55896。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

16.Apanasets O. et al. (2014) PEX5, the shuttling import receptor for peroxisomal matrix proteins, is a redox-sensitive protein. Traffic

15 (1), 94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16.Apanasets O. et al. (2014) PEX5 是过氧化物酶体基质蛋白的穿梭输入受体,是一种氧化还原敏感蛋白。交通 15 (1), 94–103。[ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

17.Hosoi KI

et al. (2017) The VDAC2-BAK axis regulates peroxisomal membrane permeability. J Cell Biol

216 (3), 709–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17.Hosoi KI 等人 (2017) VDAC2-BAK 轴调节过氧化物酶体膜通透性。细胞生物学杂志 216 (3), 709–722。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

18.Bakkenist CJ and Kastan MB (2003) DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature

421 (6922), 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18.Bakkenist CJ 和 Kastan MB (2003) DNA 损伤通过分子间自磷酸化和二聚体解离激活 ATM。自然 421 (6922), 499–506。[ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

19.Paull TT (2015) Mechanisms of ATM Activation. Annu Rev Biochem

84, 711–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19.Paull TT (2015) ATM 激活机制。Annu Rev Biochem 84, 711–38。[ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

20.Zhang J. et al. (2015) ATM functions at the peroxisome to induce pexophagy in response to ROS. Nat Cell Biol

17 (10), 1259–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20.Zhang J. et al. (2015) ATM 在过氧化物酶体起作用,诱导 pexophagage 以响应 ROS。国家细胞生物学 17 (10), 1259–1269。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

21.Jo DS

et al. (2020) Loss of HSPA9 induces peroxisomal degradation by increasing pexophagy. Autophagy

16 (11), 1989–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21.Jo DS 等人 (2020) HSPA9 的缺失通过增加 pexophagagy 诱导过氧化物酶体降解。自噬 16 (11), 1989–2003。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

22.Lee JN

et al. (2018) Catalase inhibition induces pexophagy through ROS accumulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun

501 (3), 696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22.Lee JN 等人(2018)过氧化氢酶抑制通过 ROS 积累诱导 pexophagy。生化生物物理学研究公报 501 (3), 696–702。[ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

23.Chouaib S. et al. (2017) Hypoxic stress: obstacles and opportunities for innovative immunotherapy of cancer. Oncogene

36 (4), 439–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23.Chouaib S. 等人(2017 年)缺氧应激:癌症创新免疫疗法的障碍和机会。癌基因 36 (4), 439–445。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

24.Majmundar AJ

et al. (2010) Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell

40 (2), 294–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24.Majmundar AJ 等人 (2010) 缺氧诱导因素和对缺氧应激的反应。分子细胞 40 (2), 294–309。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

25.Jain IH

et al. (2020) Genetic Screen for Cell Fitness in High or Low Oxygen Highlights Mitochondrial and Lipid Metabolism. Cell

181 (3), 716–727

e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25.Jain IH 等人(2020 年)高氧或低氧细胞适应性的遗传筛选突出了线粒体和脂质代谢。细胞 181 (3), 716–727 e11。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

26.Ackerman D. et al. (2018) Triglycerides Promote Lipid Homeostasis during Hypoxic Stress by Balancing Fatty Acid Saturation. Cell Rep

24 (10), 2596–2605

e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26.Ackerman, D. 等人(2018)甘油三酯通过平衡脂肪酸饱和度促进缺氧应激期间的脂质稳态。细胞代表 24 (10), 2596–2605 e5。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

27.Kamphorst JJ

et al. (2013) Hypoxic and Ras-transformed cells support growth by scavenging unsaturated fatty acids from lysophospholipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

110 (22), 8882–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27.Kamphorst JJ 等人(2013 年)缺氧和 Ras 转化的细胞通过从溶血磷脂中清除不饱和脂肪酸来支持生长。Proc Natl Acad Sci US A 110 (22), 8882–7。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] -

28.Nagura M. et al. (2004) Alterations of fatty acid metabolism and membrane fluidity in peroxisome-defective mutant ZP102 cells. Lipids

39 (1), 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28.Nagura M. et al. (2004) 过氧化物酶体缺陷突变体 ZP102 细胞中脂肪酸代谢和膜流动性的改变。脂质 39 (1), 43–50。[ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

29.Zoeller RA

et al. (2002) Increasing plasmalogen levels protects human endothelial cells during hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol

283 (2), H671–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29.Zoeller RA 等人 (2002) 增加缩醛磷脂水平可在缺氧期间保护人内皮细胞。美国生理学杂志心脏环形生理学 283 (2),H671–9。[ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

30.Zoeller RA

et al. (1999) Plasmalogens as endogenous antioxidants: somatic cell mutants reveal the importance of the vinyl ether. Biochem J

338 ( Pt 3), 769–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30.Zoeller RA 等人(1999)疟原蛋白作为内源性抗氧化剂:体细胞突变体揭示了乙烯基醚的重要性。生物化学杂志 338(第 3 部分),769-76。[ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

31.Li J. et al. (2007) Hyperlipidemia and lipid peroxidation are dependent on the severity of chronic intermittent hypoxia. J Appl Physiol (1985)

102 (2), 557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31.Li, J. et al. (2007) 高脂血症和脂质过氧化取决于慢性间歇性缺氧的严重程度。应用生理学杂志 (1985) 102 (2), 557–63。[ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] -

32.Zou Y. et al. (2020) Plasticity of ether lipids promotes ferroptosis susceptibility and evasion. Nature

585 (7826), 603–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32.Zou Y. et al. (2020) 醚脂的可塑性促进铁死亡的易感性和逃避。自然 585 (7826), 603–608。[ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] [ ] - 33.Walter KM et al. (2014) Hif-2alpha promotes degradation of mammalian peroxisomes by selective autophagy. Cell Metab 20 (5), 882–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pugh CW and Ratcliffe PJ (2003) Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia: role of the HIF system. Nat Med 9 (6), 677–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kapitsinou PP et al. (2014) Endothelial HIF-2 mediates protection and recovery from ischemic kidney injury. J Clin Invest 124 (6), 2396–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reiterer M. et al. (2019) Acute and chronic hypoxia differentially predispose lungs for metastases. Sci Rep 9 (1), 10246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zechner R. (2015) FAT FLUX: enzymes, regulators, and pathophysiology of intracellular lipolysis. EMBO Mol Med 7 (4), 359–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kong J. et al. (2020) Spatiotemporal contact between peroxisomes and lipid droplets regulates fasting-induced lipolysis via PEX5. Nat Commun 11 (1), 578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Binns D. et al. (2006) An intimate collaboration between peroxisomes and lipid bodies. J Cell Biol 173 (5), 719–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zechner R. et al. (2017) Cytosolic lipolysis and lipophagy: two sides of the same coin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18 (11), 671–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marino G. et al. (2014) Regulation of autophagy by cytosolic acetyl-coenzyme A. Mol Cell 53 (5), 710–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He A. et al. (2020) Acetyl-CoA Derived from Hepatic Peroxisomal beta-Oxidation Inhibits Autophagy and Promotes Steatosis via mTORC1 Activation. Mol Cell 79 (1), 30–42 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saxton RA and Sabatini DM (2017) mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 168 (6), 960–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim J. et al. (2011) AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol 13 (2), 132–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Son SM et al. (2019) Leucine Signals to mTORC1 via Its Metabolite Acetyl-Coenzyme A. Cell Metab 29 (1), 192–201 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Charles KN et al. (2020) Functional Peroxisomes Are Essential for Efficient Cholesterol Sensing and Synthesis. Front Cell Dev Biol 8, 560266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palou M. et al. (2008) Sequential changes in the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism in adipose tissue and liver in response to fasting. Pflugers Arch 456 (5), 825–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haman F. and Blondin DP (2017) Shivering thermogenesis in humans: Origin, contribution and metabolic requirement. Temperature (Austin) 4 (3), 217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikeda K. et al. (2018) The Common and Distinct Features of Brown and Beige Adipocytes. Trends Endocrinol Metab 29 (3), 191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wikstrom JD et al. (2014) Hormone-induced mitochondrial fission is utilized by brown adipocytes as an amplification pathway for energy expenditure. EMBO J 33 (5), 418–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahlabo I. and Barnard T. (1971) Observations on peroxisomes in brown adipose tissue of the rat. J Histochem Cytochem 19 (11), 670–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bagattin A. et al. (2010) Transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha promotes peroxisomal remodeling and biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 (47), 20376–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park H. et al. (2019) Peroxisome-derived lipids regulate adipose thermogenesis by mediating cold-induced mitochondrial fission. J Clin Invest 129 (2), 694–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohlemiller KK et al. (1999) Early elevation of cochlear reactive oxygen species following noise exposure. Audiol Neurootol 4 (5), 229–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Delmaghani S. et al. (2015) Hypervulnerability to Sound Exposure through Impaired Adaptive Proliferation of Peroxisomes. Cell 163 (4), 894–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heman-Ackah SE et al. (2010) A combination antioxidant therapy prevents age-related hearing loss in C57BL/6 mice. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 143 (3), 429–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Konings A. et al. (2007) Association between variations in CAT and noise-induced hearing loss in two independent noise-exposed populations. Hum Mol Genet 16 (15), 1872–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Defourny J. et al. (2019) Pejvakin-mediated pexophagy protects auditory hair cells against noise-induced damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116 (16), 8010–8017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Onomoto K. et al. (2014) Antiviral innate immunity and stress granule responses. Trends Immunol 35 (9), 420–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dixit E. et al. (2010) Peroxisomes are signaling platforms for antiviral innate immunity. Cell 141 (4), 668–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schoggins JW and Rice CM (2011) Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Curr Opin Virol 1 (6), 519–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.You J. et al. (2015) Flavivirus Infection Impairs Peroxisome Biogenesis and Early Antiviral Signaling. J Virol 89 (24), 12349–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jean Beltran PM et al. (2018) Infection-Induced Peroxisome Biogenesis Is a Metabolic Strategy for Herpesvirus Replication. Cell Host Microbe 24 (4), 526–541 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu XG et al. (2019) CHP1 Regulates Compartmentalized Glycerolipid Synthesis by Activating GPAT4. Mol Cell 74 (1), 45–58 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gordon S. (2016) Phagocytosis: An Immunobiologic Process. Immunity 44 (3), 463–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Di Cara F. et al. (2017) Peroxisome-Mediated Metabolism Is Required for Immune Response to Microbial Infection. Immunity 47 (1), 93–106 e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cader MZ et al. (2016) C13orf31 (FAMIN) is a central regulator of immunometabolic function. Nat Immunol 17 (9), 1046–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Braverman N. et al. (1997) Human PEX7 encodes the peroxisomal PTS2 receptor and is responsible for rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata. Nat Genet 15 (4), 369–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Otera H. et al. (2000) The mammalian peroxin Pex5pL, the longer isoform of the mobile peroxisome targeting signal (PTS) type 1 transporter, translocates the Pex7p.PTS2 protein complex into peroxisomes via its initial docking site, Pex14p. J Biol Chem 275 (28), 21703–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meinecke M. et al. (2010) The peroxisomal importomer constitutes a large and highly dynamic pore. Nat Cell Biol 12 (3), 273–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matsumoto N. et al. (2003) The pathogenic peroxin Pex26p recruits the Pex1p-Pex6p AAA ATPase complexes to peroxisomes. Nat Cell Biol 5 (5), 454–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]