SUMMARY 总结

Deconvolution of regulatory mechanisms that drive transcriptional programs in cancer cells is key to understanding tumor biology. Herein, we present matched transcriptome (scRNA-seq) and chromatin accessibility profiles (scATAC-seq) at single-cell resolution from human ovarian and endometrial tumors processed immediately following surgical resection. This dataset reveals the complex cellular heterogeneity of these tumors and enabled us to quantitatively link variation in chromatin accessibility to gene expression. We show that malignant cells acquire previously unannotated regulatory elements to drive hallmark cancer pathways. Moreover, malignant cells from within the same patients show substantial variation in chromatin accessibility linked to transcriptional output, highlighting the importance of intratumoral heterogeneity. Finally, we infer the malignant cell type-specific activity of transcription factors. By defining the regulatory logic of cancer cells, this work reveals an important reliance on oncogenic regulatory elements and highlights the ability of matched scRNAseq/scATACseq to uncover clinically relevant mechanisms of tumorigenesis in gynecologic cancers.

对驱动癌细胞转录程序的调控机制进行反卷积是理解肿瘤生物学的关键。在此,我们展示了手术切除后立即处理的人卵巢和子宫内膜肿瘤的单细胞分辨率的匹配转录组 (scRNA-seq) 和染色质可及性谱 (scATAC-seq)。该数据集揭示了这些肿瘤复杂的细胞异质性,并使我们能够定量地将染色质可及性的变化与基因表达联系起来。我们表明,恶性细胞获得以前未注释的调节元件来驱动标志性的癌症通路。此外,来自同一患者体内的恶性细胞显示出与转录输出相关的染色质可及性的巨大差异,突出了肿瘤内异质性的重要性。最后,我们推断转录因子的恶性细胞类型特异性活性。通过定义癌细胞的调节逻辑,这项工作揭示了对致癌调节元件的重要依赖,并强调了匹配的 scRNAseq/scATACseq 揭示妇科癌症肿瘤发生的临床相关机制的能力。

Keywords: Single-Cell Genomics, scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, Endometrial Cancer, Ovarian Cancer, Gastro-Intestinal Stromal Tumors, Intratumoral Heterogeneity, Enhancer Elements

关键字: 单细胞基因组学, scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, 子宫内膜癌, 卵巢癌, 胃肠道间质瘤, 瘤内异质性, 增强子元件

eTOC blurb eTOC 简介

Regner & Wisniewska et al. present an integrated analysis of single-cell transcriptomics and chromatin accessibility data to define the regulatory logic of malignant cell states in human gynecologic cancers. They identify thousands of salient cancer-specific distal regulatory elements and uncover differential transcription factor activity that drives intratumor heterogeneity.

Regner & Wisniewska 等人提出了对单细胞转录组学和染色质可及性数据的综合分析,以定义人类妇科癌症中恶性细胞状态的调节逻辑。他们确定了数千个突出的癌症特异性远端调节元件,并揭示了驱动肿瘤内异质性的差异转录因子活性。

Graphical Abstract 图形摘要

INTRODUCTION 介绍

Dynamic interactions between various types of malignant and non-malignant cells in solid tumors contributeto a range of biological phenomena, from cancer progression to therapeutic response. Single-cell genomic technologies refined our ability to interrogate the underlying cellular heterogeneity of tumors, but most efforts to date have been limited to transcriptomics via single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) (Patel et al., 2014, Lambrechts et al., 2018, Slyper et al., 2020, Davidson et al., 2020, Kim et al., 2020, Cochrane et al., 2020). While initial reports have been transformative, it is evident that non-coding regions of the genome, containing regulatory elements (e.g. cis-acting distal enhancer elements), contribute profoundly to tumor biology (Corces et al., 2018). These regulatory elements are often rewired and repurposed by cancer cells to drive oncogenic transcription (Roadmap Epigenomics et al., 2015, Mansour et al., 2014, Zhang et al., 2016, Roe et al., 2017, Corces et al., 2018). Thus, a deeper understanding of the regulatory logic of cancer cells will provide novel insights into the molecular underpinnings of tumor biology and heterogeneity.

实体瘤中各种类型的恶性和非恶性细胞之间的动态相互作用促成了从癌症进展到治疗反应的一系列生物现象。单细胞基因组技术提高了我们询问肿瘤潜在细胞异质性的能力,但迄今为止的大多数工作都仅限于通过单细胞 RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) 的转录组学 ( Patel et al., 2014 , Lambrechts et al., 2018 , Slyper et al., 2020 , Davidson et al., 2020 Cochrane et al., 2020 , Kim et al., 2020 , )。虽然最初的报告具有变革性,但很明显,基因组的非编码区包含调节元件(例如 顺式作用远端增强子元件),对肿瘤生物学做出了深远的贡献 ( Corces et al., 2018 )。这些调节元件通常被癌细胞重新连接和重新利用,以驱动致癌转录 ( Roadmap Epigenomics et al., 2015 , Mansour et al., 2014 , Zhang et al., 2016 Roe et al., 2017 Corces et al., 2018 )。因此,对癌细胞调控逻辑的更深入理解将为肿瘤生物学和异质性的分子基础提供新的见解。

Advancements in the assay for transposase-accessible chromatin at the single cell level (scATAC-seq) enable robust profiling of the chromatin accessibility landscape, unveiling layers of gene regulation including cis-regulatory elements (Buenrostro et al., 2015, Cusanovich et al., 2015). Together, scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq offer unprecedented resolution to reveal complex epigenetic events underlying tumor biology and give potential for the discovery of pathways governing tumorigenesis going beyond the standard taxonomic identification of cell types.

单细胞水平转座酶可及染色质检测 (scATAC-seq) 的进步能够对染色质可及性景观进行稳健分析,揭示基因调控层,包括顺式调节元件 ( Buenrostro et al., 2015 , Cusanovich et al., 2015 )。scRNA-seq 和 scATAC-seq 共同提供了前所未有的分辨率,以揭示肿瘤生物学背后的复杂表观遗传事件,并为发现控制肿瘤发生的途径提供了超越细胞类型标准分类学鉴定的潜力。

Few cancer datasets with matched scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq exist and none have been reported for human gynecologic tumors (Granja et al., 2019). Ovarian cancer (OC) and Endometrial cancer (EC) represent two of the deadliest cancers among women (Siegel et al., 2018). This is partly due to the aggressive nature of these cancers, lack of targeted therapies, and often late-stage of diagnosis. Of note, OC portends a poor prognosis and, although less common than breast cancer, it is three times more lethal (Siegel et al., 2018). EC is the 6th most frequently diagnosed cancer in women globally and is one of few cancers that is rising in mortality (Lortet-Tieulent et al., 2018, Society, 2016, Henley et al., 2018). The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) consortium has proposed molecular subtypes for these cancers, but these stratification systems fail to account for cell type composition and malignant cell heterogeneity within tumors (Cancer Genome Atlas Research, 2011, Cancer Genome Atlas Research et al., 2013). We posit that cell populations within and between patient tumors are delineated by noncoding regulatory elements that drive oncogene expression conferring enhanced proliferation, drug resistance, and/or survival.

很少有具有匹配 scRNA-seq 和 scATAC-seq 的癌症数据集,也没有关于人类妇科肿瘤的报道 ( Granja et al., 2019 )。卵巢癌 (OC) 和子宫内膜癌 (EC) 是女性中最致命的两种癌症 ( Siegel et al., 2018 )。这部分是由于这些癌症的侵袭性、缺乏靶向治疗以及通常处于诊断晚期。值得注意的是,OC 预示着预后不良,虽然不如乳腺癌常见,但它的致命性是乳腺癌的三倍 ( Siegel et al., 2018 )。EC 是全球女性中第 6 大最常被诊断出的癌症,也是死亡率上升的少数癌症之一 ( Lortet-Tieulent et al., 2018 , Society, 2016 Henley et al., 2018 , )。癌症基因组图谱 (TCGA) 联盟提出了这些癌症的分子亚型,但这些分层系统未能解释肿瘤内的细胞类型组成和恶性细胞异质性 ( Cancer Genome Atlas Research, 2011 , Cancer Genome Atlas Research et al., 2013 )。我们假设患者肿瘤内部和之间的细胞群由驱动癌基因表达的非编码调节元件描绘,从而增强增殖、耐药性和/或存活率。

Herein, we present a catalog of matched scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data for 11 human gynecologic tumors (Table 1, Table S1). This dataset, encompassing over 170,000 single cells, is of broad utility to the fields of single-cell genomics and cancer biology. By analyzing these tumors with matched scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq, we uncover clinically relevant non-coding mechanisms for intratumoral heterogeneity and pathogenesis of EC and OC. We also infer the activity of transcription factors (TFs) that interact with malignant cell type-specific regulatory elements and prioritize TFs based on predicted druggability (Tym et al., 2016, Mitsopoulos et al., 2020, Malladi et al., 2020).

在此,我们提出了 11 种人类妇科肿瘤的匹配 scRNA-seq 和 scATAC-seq 数据目录 ( Table 1 , Table S1 )。该数据集包含超过 170,000 个单细胞,在单细胞基因组学和癌症生物学领域具有广泛的用途。通过使用匹配的 scRNA-seq 和 scATAC-seq 分析这些肿瘤,我们揭示了 EC 和 OC 的瘤内异质性和发病机制的临床相关非编码机制。我们还推断了与恶性细胞类型特异性调节元件相互作用的转录因子 (TFs) 的活性,并根据预测的成药性 ( Tym et al., 2016 , Mitsopoulos et al., 2020 , Malladi et al., 2020 ) 确定 TFs 的优先级。

Table 1. Abbreviated clinical data and single-cell metadata for each patient tumor.

表 1.每个患者肿瘤的简化临床数据和单细胞元数据。

The last two columns reflect the number of cells obtained post QC and in parentheses the total number of cells estimated by Cell Ranger. Asterisks in the Tumor site column denote a metastatic event. Race column abbreviations: African American (AA), Caucasian (CAU), Asian (AS). Extended clinical data for each patient (de-identified) can be found in Table S1.

最后两列反映 QC 后获得的细胞数,括号中为 Cell Ranger 估计的细胞总数。Tumor site (肿瘤部位 ) 列中的星号表示转移事件。 种族列缩写:非裔美国人 (AA)、高加索人 (CAU)、亚洲人 (AS)。每位患者(去标识化)的扩展临床数据可在 中找到 Table S1 。

| Patient 病人 | Cancer type 癌症类型 | Tumor site 肿瘤部位 | Histology 组织学 | Stage 阶段 | Age 年龄 | Race 比赛 | BMI | scATAC-seq cells scATAC-seq 细胞 | scRNA-seq cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 患者 1 | Endometrial 子宫内膜的 | Endometrium 子宫内膜 | Endometrioid 子宫内膜样 | IA | 70 | AA | 39.89 | 6,348 (6,649) | 5,279 (5,697) |

| Patient 2 患者 2 | Endometrial 子宫内膜的 | Endometrium 子宫内膜 | Endometrioid 子宫内膜样 | IA | 70 | CAU | 30.50 | 7,248 (6,658) | 7,277 (7,963) |

| Patient 3 患者 3 | Endometrial 子宫内膜的 | Endometrium 子宫内膜 | Endometrioid 子宫内膜样 | IA | 70 | CAU | 38.55 | 4,165 (7,241) | 4,974 (6,054) |

| Patient 4 患者 4 | Endometrial 子宫内膜的 | Endometrium 子宫内膜 | Endometrioid 子宫内膜样 | IA | 49 | CAU | 55.29 | 7,597 (7,917) | 7,413 (8,110) |

| Patient 5 患者 5 | Endometrial 子宫内膜的 | Endometrium 子宫内膜 | Endometrioid 子宫内膜样 | IA | 62 | CAU | 49.44 | 6,797 (7,881) | 7,291 (8,403) |

| Patient 6 病人 6 | Endometrial 子宫内膜的 | Ovary*** 卵巢*** | Serous 浆膜 | IIIA | 74 | CAU | 29.94 | 6,643 (2,351) | 6,866 (8,009) |

| Patient 7 病人 7 | Ovarian 卵巢 | Ovary 卵巢 | Endometrioid 子宫内膜样 | IA | 76 | CAU | 34.80 | 5,924 (7,107) | 6,454 (8,295) |

| Patient 8 病人 8 | Ovarian 卵巢 | Ovary 卵巢 | HGSOC | IIB | 61 | CAU | 22.13 | 8,014 (7,898) | 7,454 (8,181) |

| Patient 9 病人 9 | Ovarian 卵巢 | Ovary 卵巢 | HGSOC | IIIC | 59 | AS | 22.37 | 9,670 (9,942) | 6,192 (6,939) |

| Patient 10 患者 10 | Ovarian 卵巢 | Ovary 卵巢 | Carcinosarcoma 肉瘤 | IVB | 69 | CAU | 23.72 | 4,439 (8,977) | 7,663 (8,984) |

| Patient 11 病人 11 | Gastric 胃的 | Ovary*** 卵巢*** | GIST | IV | 59 | CAU | 33.96 | 7,776 (11,066) | 8,660 (10,094) |

RESULTS 结果

Matched scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq of human gynecologic tumors

匹配的人妇科肿瘤的 scRNA-seq 和 scATAC-seq

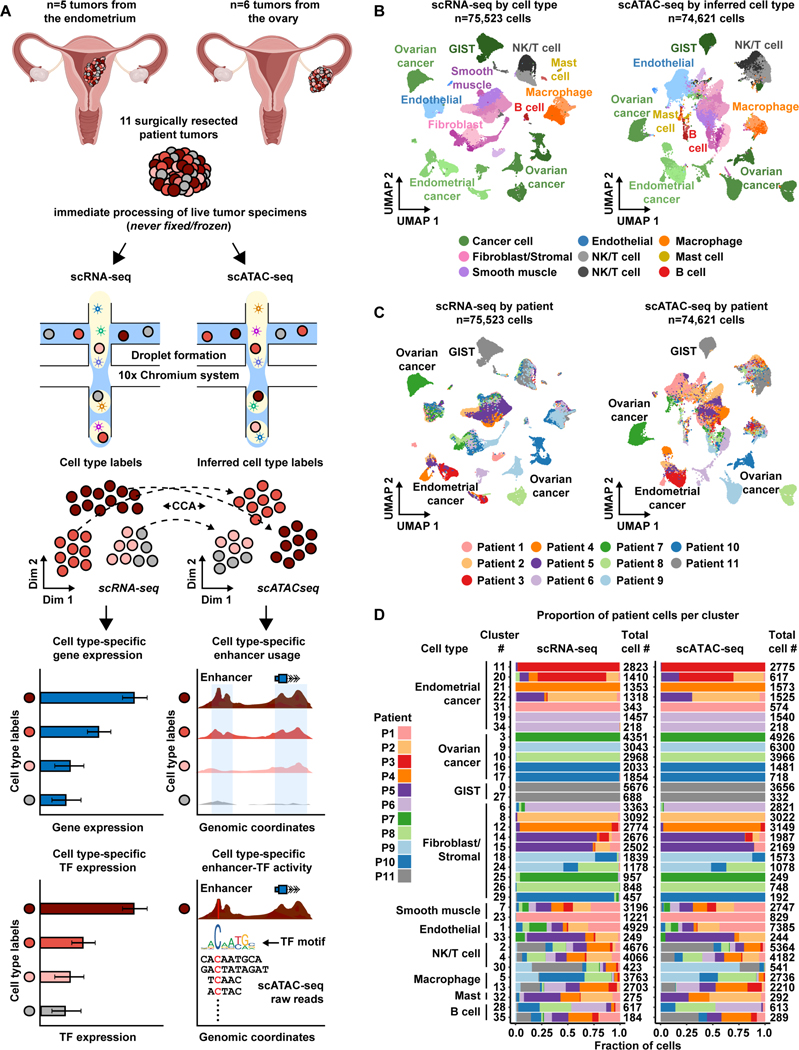

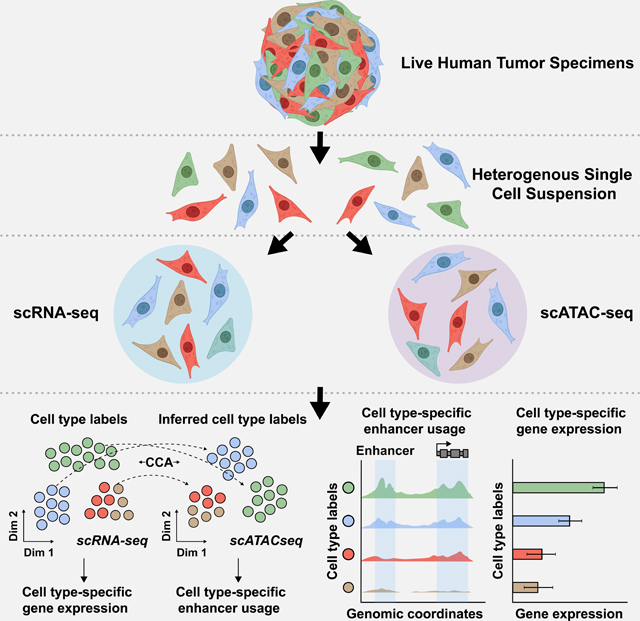

Eleven, treatment naïve, patients underwent debulking surgery with curative intent to remove tumors found either in the endometrium or ovary (Table 1, Table S1). Following surgical resection, each tumor was dissociated into a suspension of live cells and prepped for lipid droplet-based scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq (Figure 1A and STAR Methods). Tumor specimens where never frozen or fixed in any way, enabling high levels of cell viability and robust sequencing coverage in single cells. All tumors were primary tumors except for Patient 6, diagnosed as an EC that metastasized to the ovary, and Patient 11, diagnosed as a gastro-intestinal stromal tumor (GIST) that metastasized to the ovary. After quality control and doublet removal for each patient dataset (STAR Methods), we obtained 75,523 cells profiled by scRNA-seq and 74,621 cells profiled by scATAC-seq.

11 名初治患者接受了减瘤手术,目的是切除在子宫内膜或卵巢中发现的肿瘤 ( Table 1 , Table S1 )。手术切除后,将每个肿瘤解离成活细胞悬液,并准备用于基于脂滴的 scRNA-seq 和 scATAC-seq ( Figure 1A 和 STAR Methods )。肿瘤标本从未以任何方式冷冻或固定,从而在单细胞中实现高水平的细胞活力和强大的测序覆盖度。除患者 6 诊断为转移至卵巢的 EC 和患者 11 诊断为转移至卵巢的胃肠道间质瘤 (GIST) 外,所有肿瘤均为原发性肿瘤。在对每个患者数据集进行质量控制和双峰去除后 ( STAR Methods ),我们获得了 scRNA-seq 分析的 75,523 个细胞和 scATAC-seq 分析的 74,621 个细胞。

Figure 1. Overview of matched scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq workflow for patient tumors.

图 1.患者肿瘤的匹配 scRNA-seq 和 scATAC-seq 工作流程概述。

A) Cartoon showing patient tumor workflow. The female reproductive system cartoons, top, were created with BioRender.com.

A) 显示患者肿瘤工作流程的卡通片。女性生殖系统卡通片( 上图 )是用 BioRender.com 创作的。

B) UMAP plot all scRNA-seq cells color-coded by cell type across 11 patient tumors (left). UMAP plot of all scATAC-seq cells color-coded by inferred cell type across 11 patient tumors (right).Color shades denote subclusters within each cell type.

B) UMAP 绘制 11 个患者肿瘤中按细胞类型进行颜色编码的所有 scRNA-seq 细胞( 左 )。11 例患者肿瘤中按推断细胞类型进行颜色编码的所有 scATAC-seq 细胞的 UMAP 图( 右 )。颜色阴影表示每种细胞类型中的子聚类。

C) UMAP plot of scRNA-seq cells (left) and scATAC-seq cells (right) as shown in panel B but color-coded by patient of origin.

C) scRNA-seq 细胞( 左 )和 scATAC-seq 细胞( 右 )的 UMAP 图,如图 B 所示,但按原籍患者进行颜色编码。

D) Stacked bar charts showing contribution of each patient to each subcluster in scRNA-seq (left) and to each inferred cell type subcluster in scATAC-seq (right).

D) 堆叠条形图,显示每位患者对 scRNA-seq 中每个子簇( 左 )和 scATAC-seq 中每个推断细胞类型子簇( 右 )的贡献。

To analyze scRNA-seq cells from the entire cohort, we performed principal component analysis (PCA) using the top 2,000 most variably expressed genes across all 75,523 cells. Cells were classified into transcriptionally-distinct clusters with graph-based clustering using the top 50 principal components (PCs) and visualized using a Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plot. This revealed that clusters could be annotated to known cell types (Aran et al., 2019) (Figure 1B [left],

Figure S1A, Table S2, and STAR Methods) and batch effects were not a major confounder (Figure 1C, left). To identify malignant clusters across the entire cohort, we used clinical biomarker gene expression and inferred copy number amplification/deletion events (Figures S2-S4). We used expression of FDA approved biomarkers, MUC16/CA125 and WFDC2/HE4, to identify EC and OC cancer clusters (Duffy et al., 2005, Sturgeon et al., 2008, Hellström et al., 2003, Li et al., 2009, Dong et al., 2017). Expression of KIT/CD117 was used to identify GIST cancer clusters (Sarlomo-Rikala et al., 1998). Inferred copy number variation was used to help identify OC and GIST, but not EC since the disease rarely exhibits copy number variation (Berger et al., 2018).

为了分析来自整个队列的 scRNA-seq 细胞,我们使用所有 75,523 个细胞中表达最多的 2,000 个基因进行了主成分分析 (PCA)。使用前 50 个主成分 (PC) 通过基于图形的聚类将细胞分类为转录不同的簇,并使用统一流形近似和投影 (UMAP) 图进行可视化。这表明簇可以注释到已知的细胞类型 ( Aran et al., 2019 ) ( Figure 1B [ 左], Figure S1A , Table S2 和 STAR Methods ),并且批次效应不是主要的混杂因素 ( Figure 1C , 左 )。为了识别整个队列中的恶性集群,我们使用了临床生物标志物基因表达和推断的拷贝数扩增/缺失事件 ( Figures S2 - S4 )。我们使用 FDA 批准的生物标志物 MUC16/CA125 和 WFDC2/HE4 的表达来识别 EC 和 OC 癌症集群 ( Duffy et al., 2005 , Sturgeon et al., 2008 , Hellström et al., 2003 , Li et al., 2009 Dong et al., 2017 , )。KIT/CD117 的表达用于识别 GIST 癌簇 ( Sarlomo-Rikala et al., 1998 )。推断的拷贝数变异用于帮助识别 OC 和 GIST,但不是 EC,因为该疾病很少表现出拷贝数变异 ( Berger et al., 2018 )。

To analyze scATAC-seq cells from the entire cohort, we created a matrix of contiguous genomic tiles, across the genome, in which we quantified fragment counts. We performed iterative latent semantic indexing on the top 25,000 most variable genomic tiles (Cusanovich et al., 2015, Satpathy et al., 2019, Granja et al., 2021). To assign cell type cluster labels from matching scRNA-seq data to scATAC-seq cells, we used the Seurat v3 cross-modality integration approach (constrained to cells of the same patient tumor) (Figure 1B [right],

Figure S1, Table S3, and STAR Methods) (Stuart et al., 2019). This revealed scATAC-seq cells that clustered mainly by cell type and not by patient, highlighting the quality of the dataset (Figure 1C, right).

为了分析来自整个队列的 scATAC-seq 细胞,我们创建了一个跨基因组的连续基因组切片矩阵,其中我们量化了片段计数。我们对前 25,000 个最可变的基因组切片 ( Cusanovich et al., 2015 , Satpathy et al., 2019 , Granja et al., 2021 ) 进行了迭代潜在语义索引。为了将来自匹配 scRNA-seq 数据的细胞类型簇标签分配给 scATAC-seq 细胞,我们使用了 Seurat v3 跨模态整合方法(仅限于同一患者肿瘤的细胞)( Figure 1B [ 右 ] Figure S1 、 Table S3 和 STAR Methods )( Stuart et al., 2019 )。这揭示了主要按细胞类型而不是患者聚集的 scATAC-seq 细胞,突出了数据集的质量( Figure 1C , 右 )。

Overall, we found ten general cell types in the entire cohort with 36 subclusters present in both modalities. Although these subclusters vary in size, immune subclusters contain roughly equal proportions of cells across all patients, while malignant and fibroblast subclusters remain highly patient-specific (Figure 1D, Figures S5-S6). This is partly reflected by the uniqueness of each inferred CNV profile from each tumor (Figures S2-S3). Our observations are consistent with previous scRNA-seq reports in OC (Izar et al., 2020), lung cancer (Lambrechts et al., 2018), and nasopharyngeal cancer (Chen et al., 2020). These patterns likely reflect biological overlap of non-malignant cells across all patients and highlight the unique, and possibly tractable, biological features of malignant cells within each tumor.

总体而言,我们在整个队列中发现了 10 种一般细胞类型,两种模式都存在 36 个亚簇。尽管这些亚簇的大小各不相同,但免疫亚簇在所有患者中包含大致相等比例的细胞,而恶性和成纤维细胞亚簇仍然具有高度的患者特异性 ( Figure 1D , Figures S5 - S6 )。这部分反映在从每个肿瘤推断的每个 CNV 谱 ( Figures S2 - S3 ) 的唯一性上。我们的观察结果与之前在 OC ( Izar et al., 2020 )、肺癌 ( Lambrechts et al., 2018 ) 和鼻咽癌 ( ) 中的 scRNA-seq 报告一致 Chen et al., 2020 。这些模式可能反映了所有患者非恶性细胞的生物学重叠,并突出了每个肿瘤内恶性细胞的独特且可能易于处理的生物学特征。

Systematic discovery of cancer-specific distal regulatory elements (dREs) in human gynecologic cancers

在人类妇科癌症中系统发现癌症特异性远端调节元件 (dRE)

We next explored the chromatin landscape to identify distal regulatory elements that could help explain distinct biological states of these malignant cells. To identify putative regulatory elements across all scATAC-seq cells, we first carried out peak calling within each cell type subcluster and used an iterative overlap peak merging procedure to generate a peak-by-cell matrix (Zhang et al., 2008, Granja et al., 2021, Liu, 2014, Corces et al., 2018). In order to link variation in chromatin accessibility to differences in gene expression, we executed a large-scale peak-to-gene linkage analysis and developed a robust empirical false discovery rate (eFDR) procedure for determining statistically significant peak-to-gene associations in single-cell data (STAR Methods) (Granja et al., 2021, Storey and Tibshirani, 2003).

接下来,我们探索了染色质景观,以确定有助于解释这些恶性细胞的不同生物状态的远端调节元件。为了确定所有 scATAC-seq 细胞中推定的调节元件,我们首先在每个细胞类型子簇内进行峰调用,并使用迭代重叠峰合并程序生成逐个细胞的峰矩阵 ( Zhang et al., 2008 , Granja et al., 2021 , Liu, 2014 Corces et al., 2018 , )。为了将染色质可及性的变化与基因表达的差异联系起来,我们进行了大规模的峰到基因连锁分析,并开发了一种稳健的经验错误发现率 (eFDR) 程序,用于确定单细胞数据中具有统计学意义的峰与基因关联 ( STAR Methods ) ( Granja et al., 2021 , Storey and Tibshirani, 2003 )。

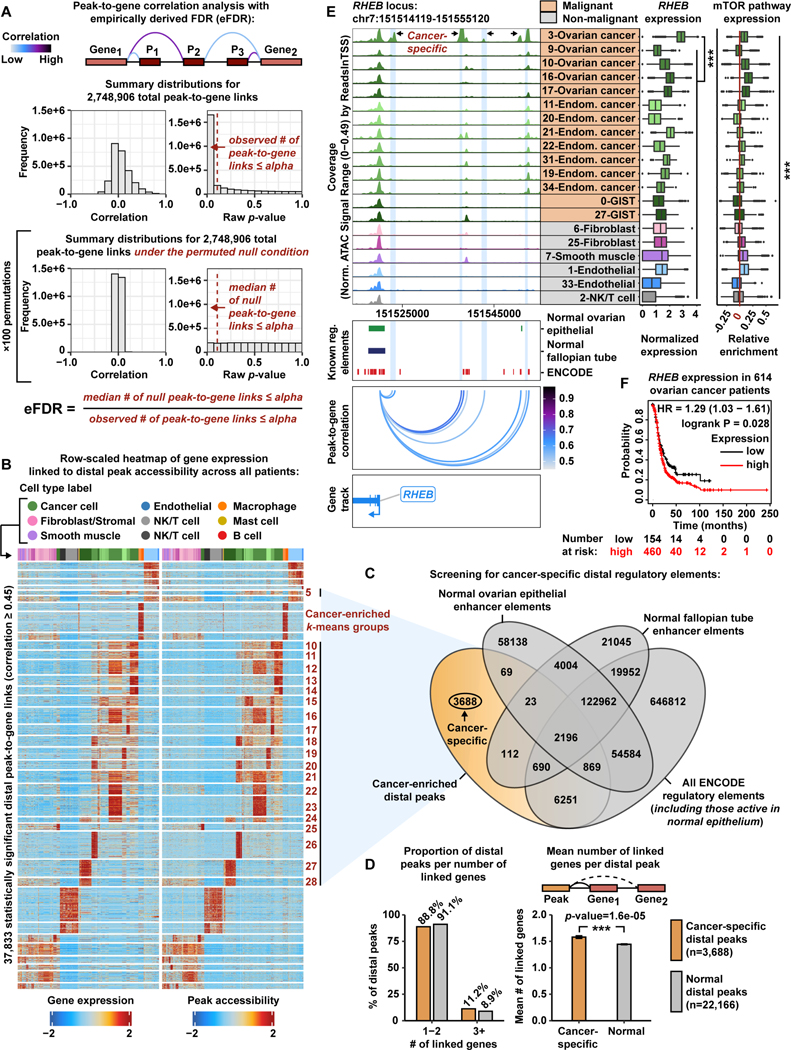

Briefly, we aggregated the sparse peak counts within groups of similar scATAC-seq cells, identified via k-nearest neighbors, to generate more informative metacell observations for our peak-to-gene correlation analysis. We then used the scATAC-seq metacells (i.e. aggregates of similar cells) to compute the correlation between accessibility of every peak and expression of every gene in cis, imputed for each scATAC-seq cell (STAR Methods). This peak-to-gene correlation analysis resulted in 2,748,906 peak-to-gene combinations in cis (Figure 2A [top], Figure S7A [top]). To estimate the eFDR, we selected a raw p-value threshold of 1e-12 and recorded the number of observed peak-to-gene associations with a raw p-value ≤ 1e-12 (see STAR Methods). The peak-to-gene correlation analysis was repeated 100 times under the permuted null condition where, for each permutation, we shuffled scATAC-seq metacell labels to break the link between peak accessibility and gene expression (Figure 2A [bottom], Figure S7A [bottom]). For every permutation, there was less correlation between peak-to-gene pairs compared to observed data and the raw p-value distribution was near uniform. The eFDR was then calculated by dividing the median number of null peak-to-gene associations with a raw pvalue ≤ 1e-12 by the number of observed associations with a raw p-value ≤ 1e-12. These data highlight the genuine biological relationships between peak accessibility and gene expression in the observed data (Figure 2A, Figure S7, and STAR Methods).

简而言之,我们汇总了通过 k 最近邻鉴定的相似 scATAC-seq 细胞组内的稀疏峰值计数,以便为我们的峰与基因相关性分析生成更多信息丰富的元细胞观察结果。然后,我们使用 scATAC-seq 元细胞(即相似细胞的聚集体)来计算每个峰的可及性与顺式中每个基因的表达之间的相关性,为每个 scATAC-seq 细胞估算 ( STAR Methods )。该峰-基因相关性分析得出 2,748,906 个顺式峰-基因组合 ( Figure 2A [top], Figure S7A [top])。为了估计 eFDR,我们选择了 1e-12 的原始 p 值阈值,并记录了观察到的与原始 p 值≤ 1e-12 的峰与基因关联的数量(参见 STAR Methods )。在置换零条件下重复峰-基因相关性分析 100 次,其中,对于每个排列,我们洗牌 scATAC-seq 元细胞标签以打破峰可及性和基因表达之间的联系 ( Figure 2A [ 底部 ], Figure S7A [ 底部 ])。对于每种排列,与观察到的数据相比,峰-基因对之间的相关性较低,原始 p 值分布几乎均匀。然后通过将原始 p 值≤ 1e-12 的零峰-基因关联的中位数除以观察到的原始 p 值≤ 1e-12 的关联数来计算 eFDR。这些数据突出了观察到的数据中峰可及性和基因表达之间的真实生物学关系( Figure 2A 、 和 Figure S7 STAR Methods )。

Figure 2. Systematic in silico identification of cancer-specific distal regulatory elements.

图 2.系统地进行癌症特异性远端调节元件的计算机识别。

A) Cartoon showing peak-to-gene correlation analysis with an eFDR (top).Histograms of correlation values and raw p-values for n=2,748,906 peak-to-gene link tests (middle) and peak-to-gene link tests under the null condition (bottom). Dashed red lines represent the alpha threshold or raw p-value cutoff of 1e-12 for calling statistically significant peak-to-gene links.

A) 漫画显示了使用 eFDR( 上图 )进行峰-基因相关性分析。n=2,748,906 个峰-基因连接测试( 中间 )和零条件下的峰-基因连接测试( 底部 )的相关值和原始 p 值的直方图。红色虚线表示 1e-12 的 alpha 阈值或原始 p 值截止值,用于调用具有统计学意义的峰到基因连接。

B) Row-scaled heatmaps of statistically significant distal peak-to-gene links. Each row represents expression of a gene (left) correlated to accessibility of a distal peak (right). Cancer-enriched k-means clusters are marked in red. Distal peaks participating in cancer-enriched k-means groups are used in the overlap analysis presented in panel C.

B) 具有统计学意义的远端峰到基因链接的行刻度热图。每行代表一个基因的表达( 左图),与远端峰的可及性( 右图)相关。富含癌症的 k-means 簇标记为红色。参与癌症富集 k-means 组的远端峰用于图 C 中呈现的重叠分析。

C) Venn diagram showing the number of cancer-specific distal peaks (orange) after overlapping the genomic coordinates of cancer-enriched distal peaks with the genomic coordinates of normal ovarian surface epithelium enhancer elements, normal fallopian tube enhancer elements, and all ENCODE regulatory element annotations (gray).

C) 维恩图显示癌症富集远端峰的基因组坐标与正常卵巢表面上皮增强子元件、正常输卵管增强子元件和所有 ENCODE 调节元件注释( 灰色 )重叠后癌症特异性远端峰的数量( 橙色 )。

D) Bar charts comparing proportion of distal peaks per number of linked genes between cancer-specific (orange) and normal (gray) distal peak groups (left).Bar chart comparing mean number of linked genes per distal peak between cancer-specific (orange) and normal (gray) distal peak groups (right). Asterisks denote a statistically significant difference (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test). Error bars represent ±1 S.E.M.

D) 比较癌症特异性( 橙色 )和正常( 灰色 )远端峰组( 左 )之间每数连锁基因的远端峰比例的条形图。比较癌症特异性( 橙色 )和正常( 灰色 )远端峰组( 右) 之间每个远端峰的平均连锁基因数的条形图。星号表示统计上显著的差异(Wilcoxon Rank Sum 检验)。误差线表示 ±1 S.E.M.

E) Browser track showing the accessibility profile at the RHEB locus across all malignant subclusters (orange) and select non-malignant subclusters (gray) (left). Putative cancer-specific dREs for RHEB are highlighted by light blue shadows. Matching scRNA-seq expression of RHEB is shown for each subcluster (middle). Asterisks denote a statistically significant difference in gene expression between cells in the 3-Ovarian cancer subcluster and all remaining subclusters (average logFC > 1.0 & Bonferroni-corrected p-value <0.01, Wilcoxon Rank Sum test). Relative expression of mTOR pathway members is shown in the box plot (right). Asterisks denote statistically significant differences in mTOR pathway expression across all subclusters (Kruskal-Wallis test, p-value <0.01). Known regulatory element annotations, as used in panel C, are shown below the browser track. Peak-to-gene loops show the correlation value between peak accessibility and RHEB expression (bottom).

E) 浏览器轨迹显示所有恶性亚簇( 橙色 )和选择非恶性亚簇( 灰色 )( 左 )的 RHEB 基因座的可及性概况。RHEB 的推定癌症特异性 dRE 以浅蓝色阴影突出显示。显示了每个子簇 ( 中间 ) 的 RHEB 的匹配 scRNA-seq 表达。星号表示在 3-卵巢癌子集群和所有剩余子集群(平均 logFC > 1.0 & Bonferroni 校正的 p 值<0.01,Wilcoxon 秩和检验)中细胞表达的统计学显著差异。mTOR 通路成员的相对表达如箱线图( 右) 所示。星号表示所有亚簇中 mTOR 通路表达的统计学显着差异(Kruskal-Wallis 检验,p 值 <0.01)。面板 C 中使用的已知调节元件注释显示在浏览器轨道下方。峰到基因环显示了峰可及性与 RHEB 表达之间的相关性值( 底部 )。

F) Kaplan-Meier survival curve based on progression-free survival for 614 OC patients stratified by high and low RHEBexpression.

F) Kaplan-Meier 生存曲线基于 614 名 OC 患者的无进展生存期,按高 RHEB 表达和低表达分层。

The peak-to-gene correlation analysis revealed 345,791 statistically significant peak-togene links (p-value ≤ 1e-12 with eFDR=0.00014) (Data S1). To identify positive regulatory effects (i.e. positive correlation between peak accessibility and gene expression), we focused on peak-to-gene links with a correlation ≥ 0.45 (n=133,811). Most of these peak-to-gene links involved intronic peaks (50.2%) and distal peaks (28.3%). Promoter and exonic peak-to-gene links were lowest among this set (11.3% and 10.2%, respectively) (Figure S7D). To unveil distal regulatory mechanisms active within these gynecologic tumors, we proceeded with the 37,833 distal peak-to-gene links in our downstream analyses (Data S1). We further categorized peak-to-gene links into 36 k-means clusters and observed highly consistent patterns between inferred gene expression and linked peak accessibility (Figure 2B). We refer to these linked distal peaks as putative distal regulatory elements (dREs). The majority of identified dREs are annotated by the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements Consortium (ENCODE), providing support for our computational approach and suggesting they are bona fide regulatory elements (Consortium, 2012, Consortium et al., 2020).

峰-基因相关性分析显示 345,791 个具有统计学意义的峰-基因链接 (p 值≤ 1e-12,eFDR=0.00014) ( Data S1 )。为了确定正调节作用 (即峰可及性与基因表达之间的正相关),我们专注于相关性≥ 0.45 (n=133,811) 的峰与基因联系。这些峰到基因的联系大多涉及内含子峰 (50.2%) 和远端峰 (28.3%)。启动子和外显子峰-基因连接在这组中最低(分别为 11.3% 和 10.2%)( Figure S7D )。为了揭示在这些妇科肿瘤中活跃的远端调节机制,我们在下游分析中进行了 37,833 个远端峰到基因链接 ( Data S1 )。我们进一步将峰与基因的联系分类为 36 个 k-means 簇,并观察到推断的基因表达和连接的峰可及性之间高度一致的模式 ( Figure 2B )。我们将这些连接的远端峰称为推定的远端调节元件 (dRE)。大多数已鉴定的 dRE 都由 DNA 元素百科全书联盟 (ENCODE) 注释,为我们的计算方法提供支持,并表明它们是真正的调节元件 ( Consortium, 2012 , Consortium et al., 2020 )。

To identify dREs specific to cancer cells across all patients, we extracted distal peaks from cancer-enriched k-means groups and carried out a genomic interval overlap analysis with epigenomic profiles from non-cancer tissues (Figure 2C, Figure S8A-E). We overlapped the genomic coordinates of our 14,043 cancer-enriched distal peaks with putative enhancer elements (defined by H3K27ac) active in cell lines derived from normal ovarian surface epithelium and normal fallopian tube secretory epithelium tissue (Coetzee et al., 2015). We also screened against all existing ENCODE regulatory elements (Consortium et al., 2020). The overlap analysis revealed 3,688 distal peaks that are not present in normal ovarian surface epithelium, normal fallopian tube secretory epithelium, nor the ENCODE database. Thus, these 3,688 distal peaks, participating in 5,827 peak-to-gene links, represent cancer-specific dREs (Data S1). The remaining distal peaks (n=22,166) represent regulatory elements that are active in normal tissue.

为了确定所有患者对癌细胞具有特异性的 dRE,我们从富含癌症的 k-means 组中提取远端峰,并与来自非癌组织的表观基因组图谱进行了基因组间隔重叠分析 ( Figure 2C , Figure S8A - E )。我们将 14,043 个富含癌症的远端峰的基因组坐标与源自正常卵巢表面上皮和正常输卵管分泌上皮组织的细胞系中活跃的推定增强子元件(由 H3K27ac 定义)重叠 ( Coetzee et al., 2015 )。我们还筛选了所有现有的 ENCODE 监管元件 ( Consortium et al., 2020 )。重叠分析揭示了 3,688 个远端峰,这些峰不存在于正常卵巢表面上皮、正常输卵管分泌上皮和 ENCODE 数据库中。因此,这 3,688 个远端峰参与 5,827 个峰到基因的联系,代表癌症特异性 dRE ( Data S1 )。其余远端峰 (n=22,166) 代表在正常组织中活跃的调节元件。

To further characterize cancer-specific dREs, we quantified the linked target genes per distal peak in both cancer-specific and normal peak groups. Strikingly, the cancer-specific peaks link to more genes (mean=1.58) compared to the non-malignant peaks (mean=1.44) (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, p-value=1.6e-05) (Figure 2D, Figure S8F-I). Previous studies have proposed similar estimates of the number of putative target genes per dRE and we anticipate this difference to be magnified in a larger group of patients (Mills et al., 2020, Moore et al., 2020, Corces et al., 2018).

为了进一步表征癌症特异性 dREs,我们量化了癌症特异性峰组和正常峰组中每个远端峰的连锁靶基因。引人注目的是,与非恶性峰 (平均值 = 1.44) 相比,癌症特异性峰与更多的基因 (平均值 = 1.58) 相关联 ( Figure 2D , - ) ( , )。 I Figure S8F 以前的研究已经对每个 dRE 的推定靶基因数量提出了类似的估计,我们预计这种差异会在更大的患者群体中被放大 ( Mills et al., 2020 , Moore et al., 2020 , Corces et al., 2018 )。

We found many salient instances of cancer-specific dREs linked to upregulated genes in malignant cell populations measured by scRNA-seq (Data S1). For example, the hallmark mTOR pathway regulator RHEB is significantly upregulated in the subcluster labeled as 3-Ovarian cancer, that comes from Patient 7 diagnosed with endometrioid OC (Figure 2E, Table 1, Table S1) (Yang et al., 2017). This subcluster of malignant cells also shows positive enrichment for the mTOR pathway gene signature (Liberzon et al., 2015) (see STAR Methods) (Kruskal-Wallis test, p-value <0.01). We found strong chromatin accessibility signal at the RHEB promoter across all malignant populations, but we highlight the marked increases in accessibility of four cancer-specific dREs enriched in the 3-Ovarian cancer subcluster (Figure 2E). Together, this offers a possible mechanism for mTOR pathway dysregulation through oncogenic dREs enriched in malignant cells of endometrioid OC. Indeed, high RHEB expression is prognostic of worse outcome in OC patients (Figure 2F and Table S4) (Gyorffy et al., 2012).

我们发现了许多癌症特异性 dRE 的显着实例,这些 dRE 与通过 scRNA-seq 测量的恶性细胞群中的上调基因有关 ( Data S1 )。例如,标志性的 mTOR 通路调节因子 RHEB 在标记为 3-卵巢癌的亚簇中显著上调,该亚簇来自诊断为子宫内膜样 OC 的患者 7 ( Figure 2E , Table 1 , Table S1 ) ( Yang et al., 2017 )。该恶性细胞亚簇也显示 mTOR 通路基因特征 ( Liberzon et al., 2015 ) 的阳性富集 ( ) (参见 ) (Kruskal-Wallis STAR Methods 检验,p 值 <0.01)。我们在所有恶性人群的 RHEB 启动子处发现了强烈的染色质可及性信号,但我们强调了在 3-卵巢癌亚簇中富集的四种癌症特异性 dRE 的可及性显着增加 ( Figure 2E )。总之,这提供了一种可能的机制,通过子宫内膜样 OC 恶性细胞中富集的致癌 dRE 导致 mTOR 通路失调。事实上,高 RHEB 表达预示着 OC 患者预后较差 ( Figure 2F 和 Table S4 ) ( Gyorffy et al., 2012 )。

Our eFDR peak-to-gene linkage and genomic interval overlap analyses revealed additional putative cancer-specific dREs for clinical biomarkers CA125 andCD117 in EC/OC and GIST, respectively (Data S1). These genes are also predictive of poor survival in OC and gastric cancer, respectively (Table S4). Together with our findings for RHEB, this suggests that molecular rewiring of dREs play critical roles in the pathogenesis of gynecologic malignancies and have important clinical implications (Gyorffy et al., 2012, Szasz et al., 2016).

我们的 eFDR 峰-基因连锁和基因组间隔重叠分析揭示了 EC/OC 和 GIST 中临床生物标志物 CA125 和 CD117 的额外推定癌症特异性 dREs ( Data S1 )。这些基因也分别预测 OC 和胃癌的生存率差 ( Table S4 )。结合我们对 RHEB 的研究结果,这表明 dRE 的分子重新布线在妇科恶性肿瘤的发病机制中起关键作用,具有重要的临床意义 ( Gyorffy et al., 2012 , Szasz et al., 2016 )。

To transition from the full cohort analysis into cancer-type specific analyses, and identify even finer transcriptomic and epigenomic differences, we performed pseudo-bulk clustering analysis (Kimes et al., 2017) (STAR Methods). This analysis revealed two groups of patient tumors that were conserved across data types: Patients 1–5 (endometrioid endometrial cancer (EEC)) and Patients 8 & 9 (high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC)). These groupings reflect the original histological classifications in Table 1. Interestingly, tumors from Patient 6 and Patient 10 are more similar to the HGSOC tumors in terms of pseudo-bulk RNA-seq, but are more similar to EEC tumors in terms of pseudo-bulk ATAC-seq (Figure S9).

为了从完整的队列分析过渡到癌症类型特异性分析,并确定更精细的转录组学和表观基因组学差异,我们进行了伪批量聚类分析 ( Kimes et al., 2017 ) ( STAR Methods )。该分析揭示了两组跨数据类型保守的患者肿瘤:患者 1-5 (子宫内膜样子宫内膜癌 (EEC)) 和患者 8 & 9 (高级别浆液性卵巢癌 (HGSOC))。这些分组反映了 中的 Table 1 原始组织学分类。有趣的是,患者 6 和患者 10 的肿瘤在假大体 RNA-seq 方面与 HGSOC 肿瘤更相似,但在假大量 ATAC-seq 方面更类似于 EEC 肿瘤 ( Figure S9 )。

Cancer-specific regulatory mechanisms in Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer

子宫内膜样子宫内膜癌的癌症特异性调节机制

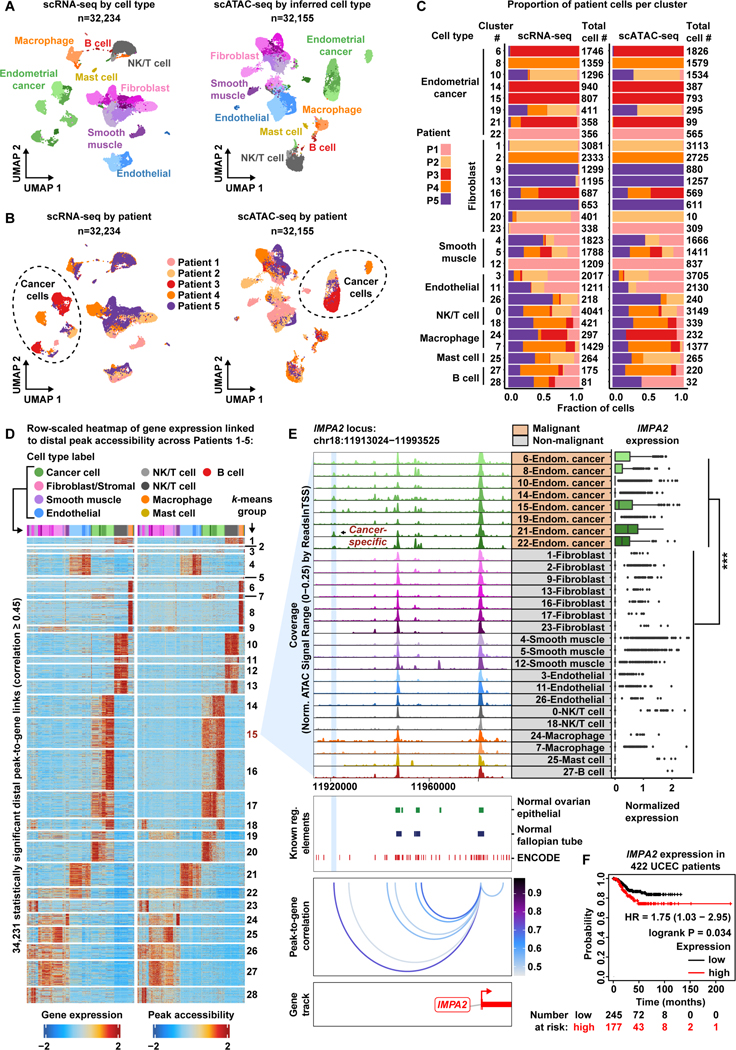

EC is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States and the endometrioid histologic type accounts for a majority of cases (Siegel et al., 2021, Ritterhouse and Howitt, 2016). To analyze the EEC patient cohort, we merged all cells from Patients 1–5, resulting in 32,234 cells profiled by scRNA-seq and 32,155 cells profiled by scATAC-seq (STAR Methods). We found that cells clustered mainly by cell type and not by patient, suggesting batch effects were not a major confounder (Figure 3A-B, Figure S10). Overall, we observed eight general cell types across Patients 1–5 with 29 subclusters in scRNA-seq and 28 subclusters in scATAC-seq. In scATAC-seq, the 20-Fibroblast subcluster had only 10 cells and was therefore removed from downstream analysis. We next screened for malignant subclusters using the EC biomarkers MUC16/CA125 and WFDC2/HE4 (Figure S11) (Dong et al., 2017, Li et al., 2009). Again, we observed that fibroblast/stromal and EC subclusters were highly patient-specific (Figure 3C, Figure S10). We also highlight that four subclusters are almost entirely formed by cells coming from Patient 3 (6-,14-,15- and 21-Endometrial cancer), suggesting a high degree of intratumoral heterogeneity within this tumor.

EC 是美国最常见的妇科恶性肿瘤,子宫内膜样组织学类型占大多数病例 ( Siegel et al., 2021 , Ritterhouse and Howitt, 2016 )。为了分析 EEC 患者队列,我们合并了患者 1-5 的所有细胞,得到 32,234 个细胞通过 scRNA-seq 分析,32,155 个细胞由 scATAC-seq 分析 ( STAR Methods )。我们发现细胞主要按细胞类型聚集,而不是按患者聚集,这表明批次效应不是主要的混杂因素 ( Figure 3A - B , Figure S10 )。总体而言,我们在患者 1-5 中观察到 8 种一般细胞类型,其中 scRNA-seq 中有 29 个子簇,scATAC-seq 中有 28 个子簇。在 scATAC-seq 中,20-成纤维细胞亚簇只有 10 个细胞,因此从下游分析中删除。接下来,我们使用 EC 生物标志物 MUC16/CA125 和 WFDC2/HE4 ( Figure S11 ) ( Dong et al., 2017 , Li et al., 2009 ) 筛选恶性亚群。同样,我们观察到成纤维细胞/基质和 EC 亚簇具有高度的患者特异性 ( Figure 3C , Figure S10 )。我们还强调,四个亚簇几乎完全由来自患者 3 (6-、14-、15- 和 21-子宫内膜癌)的细胞形成,这表明该肿瘤内存在高度的瘤内异质性。

Figure 3. A cancer-specific distal regulatory element helps drive IMPA2 expression within the Endometroid Endometrial Cancer patient cohort.

图 3.癌症特异性远端调节元件有助于驱动子宫内膜癌患者队列中的 IMPA2 表达。

A) UMAP plot of scRNA-seq cells color-coded by cell types found in Patients 1–5 (left). UMAP plot of scATAC-seq cells color-coded by inferred cell type across Patients 1–5 (right).

A) 按患者 1-5 中发现的细胞类型进行颜色编码的 scRNA-seq 细胞的 UMAP 图( 左)。 患者 1-5 中按推断细胞类型进行颜色编码的 scATAC-seq 细胞的 UMAP 图( 右 )。

B) UMAP plot of scRNA-seq cells as shown in panel A but color-coded by patient of origin (left). UMAP plot of scATAC-seq cells as shown in panel A but color-coded by patient of origin (right).

B) scRNA-seq 细胞的 UMAP 图,如图 A 所示,但按原始患者( 左 )进行颜色编码。scATAC-seq 细胞的 UMAP 图如图 A 所示,但按原始患者进行颜色编码( 右 )。

C) Stacked bar charts showing contribution of each patient to each subcluster.

C) 显示每个患者对每个子集群的贡献的堆叠条形图。

D) Row-scaled heatmaps of statistically significant distal peak-to-gene links where each row represents expression of a gene (left) correlated to accessibility of a distal peak (right). Select k-means clusters containing IMPA2 are marked in red text.

D) 具有统计学意义的远端峰到基因链接的行刻度热图,其中每行代表一个基因的表达( 左 )与远端峰的可及性( 右 )相关。包含 IMPA2 的选定 k 均值群集以红色文本标记。

E) Browser track showing the accessibility profile at the IMPA2 locus across all cell type subclusters (left). Subclusters are color-coded either malignant (orange) or non-malignant (gray). Putative cancer-specific dRE of IMPA2 is highlighted by the light blue shadow. Matching scRNA-seq expression of IMPA2 is shown for all subclusters (right). Asterisks denote a statistically significant difference in gene expression between cells in marked subclusters when aggregated (average logFC = 0.23 & Bonferroni-corrected p-value <0.01, Wilcoxon Rank Sum test). Known regulatory element annotations for normal ovarian surface epithelium, normal fallopian tube, and ENCODE, are shown below the browser track. Peak-to-gene loops show the correlation value between peak accessibility and IMPA2 expression (bottom).

E) 浏览器轨迹显示所有细胞类型子簇中 IMPA2 基因座的可及性概况( 左 )。子聚类以颜色编码为恶性 ( 橙色 ) 或非恶性 ( 灰色 )。IMPA2 的推定癌症特异性 dRE 由浅蓝色阴影突出显示。显示了所有子簇的 IMPA2 的匹配 scRNA-seq 表达( 右图 )。星号表示在聚合时标记的子集群中细胞间基因表达的统计学显著差异(平均 logFC = 0.23 & Bonferroni 校正的 p 值 <0.01,Wilcoxon 秩和检验)。正常卵巢表面上皮、正常输卵管和 ENCODE 的已知调节元件注释显示在浏览器轨道下方。峰到基因环显示了峰可及性与 IMPA2 表达之间的相关性值( 下图 )。

F) Kaplan–Meier survival curve based on recurrence-free survival for 422 Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma (UCEC) patients stratified by high and low IMPA2 expression.

F) 基于 422 名子宫体子宫内膜癌 (UCEC) 患者的无复发生存期的 Kaplan-Meier 生存曲线,按 IMPA2 高表达和低表达分层。

Next, we wanted to better understand transcriptional differences between these EEC subclusters and if any patterns could be explained by variation in chromatin accessibility. We performed the cancer-specific peak-to-gene linkage analysis in the EEC cohort and identified 324,626 peak-to-gene links (p-value ≤ 1e-12 with eFDR = 5.5e-5), of which 34,231 were distal with a correlation ≥ 0.45 (Data S1, Figure 3D). Comparison to normal reference epigenomic profiles identified 1,943 putative cancer-specific distal peaks forming 2,950 cancer-specific peak-to-gene links (Data S1) (Consortium et al., 2020, Coetzee et al., 2015). Interestingly, we observe the same increase in number of genes linked to cancer-specific peaks relative to normal peaks for the EEC patient cohort (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, p-value=4.23e-05).

接下来,我们想更好地了解这些 EEC 亚簇之间的转录差异,以及是否有任何模式可以用染色质可及性的变化来解释。我们在 EEC 队列中进行了癌症特异性峰-基因连锁分析,确定了 324,626 个峰-基因链接 (p 值≤ 1e-12,eFDR = 5.5e-5),其中 34,231 个是远端的,相关性≥ 0.45 ( Data S1 , Figure 3D )。与正常参考表观基因组图谱的比较确定了 1,943 个推定的癌症特异性远端峰,形成 2,950 个癌症特异性峰到基因连接 ( Data S1 ) ( Consortium et al., 2020 , Coetzee et al., 2015 )。有趣的是,我们观察到相对于 EEC 患者队列的正常峰,与癌症特异性峰相关的基因数量增加相同(Wilcoxon 秩和检验,p 值 = 4.23e-05)。

To evaluate if these dREs were shared across EEC patients, we repeated the peak-to-gene linkage analysis for each patient individually using the same set of peaks from the full EEC analysis (Figure S12A). We asked what proportion of the 34,231 dREs, or peak-gene pairs, were recoverable in each patient. The patient-specific analyses from Patients 1–5 recovered 49.68%, 52.03%, 40.91%, 62.17% and 52.32% of the original EEC dREs, respectively (Figure S12B). Moreover, we found that 17.23% of the original EEC dREs were recovered in every patient-specific analysis. Thus, multiple patients participate in these putative regulatory relationships.

为了评估这些 dRE 是否在 EEC 患者之间共享,我们使用完整 EEC 分析中的同一组峰对每位患者单独重复峰到基因连锁分析 ( Figure S12A )。我们询问了每位患者 34,231 个 dRE 或峰值基因对中可恢复的比例。来自患者 1-5 的患者特异性分析分别恢复了 49.68%、52.03%、40.91%、62.17% 和 52.32% 的原始 EEC dRE ( Figure S12B )。此外,我们发现在每次患者特异性分析中都回收了 17.23% 的原始 EEC dRE。因此,多个患者参与这些假定的调节关系。

Next, we wanted to investigate the extent to which cancer-specific dREs are rewired in malignant cell populations relative to normal cell populations of the EEC cohort. We repeated our peak-to-gene linkage analysis for malignant and non-malignant fractions of the EEC cohort independently and assessed how many cancer-specific dREs were recovered in each fraction (Figure 3C, Figure S13). We identified 27,738 dREs in the malignant-specific analysis and 34,172 dREs in the non-malignant analysis (Figure S13B

top). The malignant-specific analysis recovered more of the 2,950 cancer-specific dREs than the non-malignant analysis (47.5% versus 6.3%, respectively) (Figure S13B, bottom). These data suggest that the distal regulatory landscape is rewired in malignancy relative to normal cell states.

接下来,我们想研究相对于 EEC 队列的正常细胞群,癌症特异性 dRE 在恶性细胞群中重新连接的程度。我们独立地重复了 EEC 队列的恶性和非恶性部分的峰-基因连锁分析,并评估了每个部分中回收了多少癌症特异性 dRE ( Figure 3C , Figure S13 )。我们在恶性特异性分析中确定了 27,738 个 dREs,在非恶性分析中确定了 34,172 个 dREs ( Figure S13B 上图)。恶性特异性分析比非恶性分析回收了 2,950 例癌症特异性 dRE 中的更多 (分别为 47.5% 和 6.3%)( Figure S13B , 底部 )。这些数据表明,相对于正常细胞状态,恶性肿瘤中的远端调节景观被重新连接。

We then identified three clear examples of cancer-specific dREs that explain upregulated gene expression in malignant populations relative to normal cell populations in the EEC cohort. For example, there is increased IMPA2 expression in the malignant fraction of the EEC cohort and increased chromatin accessibility of a cancer-specific dRE within the IMAP2 locus (Figure 3E). IMPA2 encodes the inositol monophosphatase 2 protein involved in phosphatidylinositol signaling. While few works have reported a role for IMPA2 in cancer, high IMPA2 expression is predictive of poor survival in Uterine Corpus Endometrioid Carcinoma (UCEC) patients (Figure 3F, Table S4) (Zhang et al., 2020, Nagy et al., 2021, Ohnishi et al., 2007). We also found three clear cancer-specific dREs linked to increased SOX9 expression in the malignant fraction of the EEC cohort (Data S1). Since high SOX9 expression portends a worse outcome for UCEC patients and SOX9 has been implicated in formation of endometrial hyperplastic lesions in EC, these data may offer insights into non-coding mechanisms behind carcinogenesis of the endometrium (Table S4) (Saegusa et al., 2012, Gonzalez et al., 2016, Nagy et al., 2021). Finally, we note that CD24 is highly expressed in the malignant fraction of the EEC cohort, and we highlight three cancer-specific dREs linked to CD24 expression (Data S1). CD24 is reported to be an effective differentiator between endometrial hyperplastic lesions and EC (Nagy et al., 2021, Kim et al., 2009). Additionally, increased CD24 expression offers resistance to chemotherapeutic agents and facilitates immune escape from macrophage phagocytosis in endometrial carcinoma cells (Lin et al., 2021, Pandey et al., 2010). These clinically relevant oncogenic dREs are just a snapshot of the altered regulatory landscape in EEC. We have tabulated all significant cancer-specific dRE-gene interactions in Data S1.

然后,我们确定了癌症特异性 dRE 的三个明确示例,这些示例解释了相对于 EEC 队列中正常细胞群的恶性群体中基因表达上调。例如,EEC 队列恶性组分中 IMPA2 的表达增加,并且 IMAP2 基因座内癌症特异性 dRE 的染色质可及性增加 ( Figure 3E )。IMPA2 编码参与磷脂酰肌醇信号传导的肌醇单磷酸酶 2 蛋白。虽然很少有研究报道 IMPA2 在癌症中的作用,但 IMPA2 的高表达可预测子宫体子宫内膜样癌 (UCEC) 患者的生存率差 ( Figure 3F , Table S4 ) ( Zhang et al., 2020 , Nagy et al., 2021 , Ohnishi et al., 2007 )。我们还发现了 3 个明显的癌症特异性 dRE 与 EEC 队列恶性部分的 SOX9 表达增加有关 ( Data S1 )。由于 SOX9 高表达预示着 UCEC 患者预后更差,并且 SOX9 与 EC 中子宫内膜增生病变的形成有关,因此这些数据可能有助于了解子宫内膜致癌背后的非编码机制 ( Table S4 ) ( Saegusa et al., 2012 , Gonzalez et al., 2016 , Nagy et al., 2021 )。最后,我们注意到 CD24 在 EEC 队列的恶性部分中高度表达,我们强调了与 CD24 表达相关的三种癌症特异性 dRE ( Data S1 )。据报道,CD24 是子宫内膜增生病变和 EC 之间的有效鉴别因子 ( Nagy et al., 2021 , Kim et al., 2009 )。此外,CD24 表达增加提供了对化疗药物的耐药性,并促进了子宫内膜癌细胞中巨噬细胞吞噬作用的免疫逃逸 ( Lin et al., 2021 、 Pandey et al., 2010 )。 这些临床相关的致癌 dRE 只是 EEC 监管格局改变的一个快照。我们已经将所有重要的癌症特异性 dRE 基因相互作用制成表格。 Data S1

Cancer cell populations of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer acquire cancer-specific dREs for genes involved in drug resistance

高级别浆液性卵巢癌的癌细胞群获得参与耐药性基因的癌症特异性 dRE

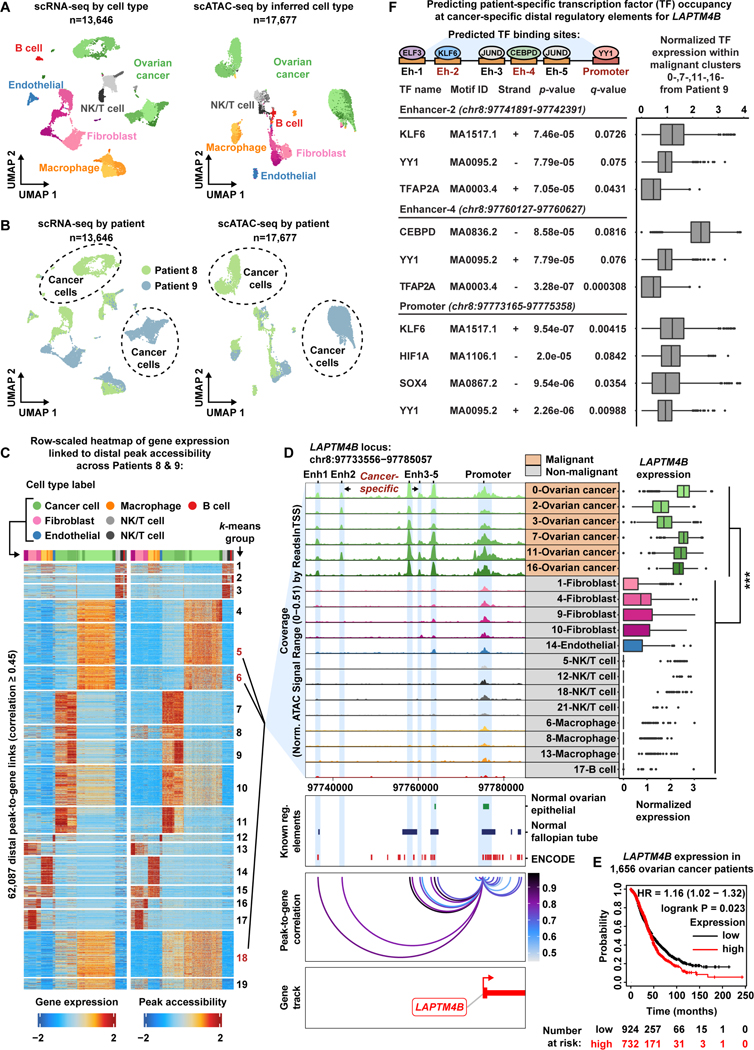

HGSOC is the most common histologic type of OC and is characterized by high copy number alterations and few driver mutations, which is thought to account for the clinical aggressiveness of this disease (Coward et al., 2015, Macintyre et al., 2018). To analyze the HGSOC patient cohort, we merged all cells from Patients 8 & 9, resulting in 13,646 cells profiled by scRNA-seq and 17,677 cells profiled by scATAC-seq (STAR Methods). Overall, we observed six general cell types across Patients 8 & 9 with 24 subclusters in scRNA-seq and 19 subclusters in scATAC-seq. In scATAC-seq, five cell type subclusters had less than 30 cells and were therefore removed from downstream analysis. (Figure 4A-B, Figure S14). We identified malignant subclusters using inferred CNV events and expression of the OC biomarkers MUC16/CA125 and WFDC2/HE4 (Figure S15) (Li et al., 2009, Duffy et al., 2005, Hellström et al., 2003, Sturgeon et al., 2008). Again, we observed that the fibroblast/stromal and OC subclusters are highly patient-specific, reflecting the biological uniqueness of malignant and fibroblast populations from each patient tumor as partly supported by their distinct inferred CNV profiles (Figure S3 and Figure S14). Of note, Patient 9 has four malignant subclusters suggesting a high degree of intratumoral heterogeneity within this tumor (Figure S14).

HGSOC 是 OC 最常见的组织学类型,其特征是高拷贝数改变和很少的驱动突变,这被认为是该疾病临床侵袭性的原因 ( Coward et al., 2015 , Macintyre et al., 2018 )。为了分析 HGSOC 患者队列,我们合并了患者 8 和 9 的所有细胞,得到 13,646 个细胞被 scRNA-seq 分析,17,677 个细胞被 scATAC-seq 分析 ( STAR Methods )。总体而言,我们在患者 8 和 9 中观察到了 6 种一般细胞类型,其中 scRNA-seq 中有 24 个子簇,scATAC-seq 中有 19 个子簇。在 scATAC-seq 中,5 个细胞类型亚簇的细胞数少于 30 个,因此从下游分析中删除。( Figure 4A - B , Figure S14 )。我们使用推断的 CNV 事件和 OC 生物标志物 MUC16/CA125 和 WFDC2/HE4 的表达 ( Figure S15 ) ( Li et al., 2009 ) ( , Duffy et al., 2005 , Hellström et al., 2003 , Sturgeon et al., 2008 ) 鉴定了恶性亚群。同样,我们观察到成纤维细胞/基质和 OC 亚簇具有高度的患者特异性,反映了来自每个患者肿瘤的恶性和成纤维细胞群的生物学独特性,部分由它们不同的推断 CNV 谱 ( Figure S3 和 Figure S14 )支持。值得注意的是,患者 9 有 4 个恶性亚簇,表明该肿瘤内部存在高度的瘤内异质性 ( Figure S14 )。

Figure 4. Malignant populations of the High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer patient cohort acquire novel enhancer-like elements that drive LAPTM4B expression.

图 4.高级别浆液性卵巢癌患者队列的恶性群体获得驱动 LAPTM4B 表达的新型增强子样元件。

A) UMAP plot of scRNA-seq cells color-coded by cell types found in Patients 8 and 9 (left). UMAP plot of scATAC-seq cells color-coded by inferred cell type across Patients 8 and 9 (right).

A) 在患者 8 和 9 中发现的按细胞类型进行颜色编码的 scRNA-seq 细胞的 UMAP 图( 左 )。患者 8 和 9 中按推断的细胞类型进行颜色编码的 scATAC-seq 细胞的 UMAP 图( 右 )。

B) UMAP plot of scRNA-seq cells as seen in panel A but color-coded by patient of origin (left). UMAP plot of scATAC-seq cells as seen in panel A but color-coded by patient of origin (right).

B) scRNA-seq 细胞的 UMAP 图,如图 A 所示,但按原籍患者( 左 )进行颜色编码。scATAC-seq 细胞的 UMAP 图如图 A 所示,但按原籍患者进行颜色编码( 右 )。

C) Row-scaled heatmaps of statistically significant distal peak-to-gene links where each row represents expression of a gene (left) correlated to accessibility of a distal peak (right). Select k-means clusters containing LAPTM4B are marked in red text.

C) 具有统计学意义的远端峰到基因链接的行缩放热图,其中每行代表一个基因的表达( 左 )与远端峰的可及性( 右 )相关。选择包含 LAPTM4B 的 k 均值群集,这些群集以红色文本标记。

D) Browser track showing the accessibility profile at the LAPTM4B locus across all subclusters (left). Subclusters are color-coded either malignant (orange) or non-malignant (gray). Putative dREs of LAPTM4B are highlighted by light blue shadows. Matching scRNA-seq expression of LAPTM4B is shown in the box plot (right) for all subclusters. Asterisks denote a statistically significant difference in gene expression between cells in marked subclusters when aggregated (average logFC = 1.77 & Bonferroni-corrected p-value <0.01, Wilcoxon Rank Sum test). Known regulatory element annotations for normal ovarian surface epithelium, normal fallopian tube, and ENCODE, are shown below the browser track. Peak-to-gene loops show the correlation value between peak accessibility and LAPTM4B expression (bottom).

D) 浏览器轨迹,显示所有子集群中 LAPTM4B 位点的可访问性概况( 左 )。子聚类以颜色编码为恶性 ( 橙色 ) 或非恶性 ( 灰色 )。推定的 LAPTM4B dRE 由浅蓝色阴影突出显示。所有子簇的匹配 scRNA-seq 表达 LAPTM4B 显示在箱形图( 右 )中。星号表示在标记的子集群中,当聚合时(平均 logFC = 1.77 & Bonferroni 校正的 p 值<0.01,Wilcoxon 秩和检验)在统计学上显著的差异。正常卵巢表面上皮、正常输卵管和 ENCODE 的已知调节元件注释显示在浏览器轨道下方。峰到基因环显示了峰可及性与 LAPTM4B 表达之间的相关性值( 下图 )。

E) Kaplan-Meier survival curve based on overall survival for 1,656 OC patients stratified by high and low LAPTM4B expression.

E) 基于 1,656 名 OC 患者的总生存期的 Kaplan-Meier 生存曲线,按高表达和低 LAPTM4B 表达分层。

F) Summary cartoon and table of Find Individual Motif Occurrences (FIMO) predictions within Enhancer 2, Enhancer 4 and LAPTM4B promoter (top, middle, bottom, respectively). Matching scRNA-seq TF expression in the malignant fraction of Patient 9 is shown in the box plots (right).

F) Enhancer 2、Enhancer 4 和 LAPTM4B 启动子( 分别为顶部、中间、底部 )中的查找单个基序出现 (FIMO) 预测摘要卡通和表格。患者 9 恶性组分中匹配的 scRNA-seq TF 表达如箱线图所示( 右 )。

To understand the regulatory landscape of these subclusters, we carried out the peak-to-gene linkage analysis to identify putative cancer-specific dREs driving the transcriptional profiles of malignant populations. This analysis identified 486,293 statistically significant (p-value ≤ 1e-12 with eFDR = 2.1e-06) peak-to-gene links, of which 62,087 were distal with a correlation ≥ 0.45 (Data S1, Figure 4C). The genomic interval overlap analysis identified 5,202 putative cancer-specific distal peaks forming 11,134 cancer-specific peak-to-gene links (Data S1) (Consortium et al., 2020, Coetzee et al., 2015). Overall, cancer-specific peaks linked to more genes on average relative to the normal peaks for the HGSOC cohort (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, p-value=6.6e-12). We again investigated the extent to which the cancer-specific dREs are rewired in malignant cell populations of the HGSOC cohort and found that a malignant-specific analysis recovered more of the 11,134 cancer-specific dREs than the non-malignant analysis (63.6% versus 3.9%, respectively) (Figure S16).

为了了解这些亚集群的调控格局,我们进行了峰-基因连锁分析,以确定驱动恶性群体转录谱的假定癌症特异性 dRE。该分析确定了 486,293 个具有统计学意义的 (p 值≤ 1e-12,eFDR = 2.1e-06) 峰到基因链接,其中 62,087 个是远端的,相关性≥ 0.45 ( Data S1 , Figure 4C )。基因组间隔重叠分析确定了 5,202 个推定的癌症特异性远端峰,形成 11,134 个癌症特异性峰到基因链接 ( Data S1 ) ( Consortium et al., 2020 , Coetzee et al., 2015 )。总体而言,相对于 HGSOC 队列的正常峰,癌症特异性峰平均与更多基因相关 (Wilcoxon 秩和检验,p 值 = 6.6e-12)。我们再次调查了癌症特异性 dRE 在 HGSOC 队列的恶性细胞群中重新连接的程度,发现恶性特异性分析比非恶性分析回收了 11,134 个癌症特异性 dRE 中的更多(分别为 63.6% 和 3.9%)( Figure S16 )。

Of the 11,134 cancer-specific dREs in the HGSOC cohort, we highlight two examples of cancer-specific gene regulation in the malignant fraction. PI3, encoding peptidase inhibitor 3 (Elafin protein), is highly expressed in the malignant fraction and its upregulation can be explained by four cancer-specific dREs (Data S1). Not only is PI3 predictive of poor survival in serous ovarian cancer patients, it is implicated in OC chemoresistance and confers OC cells a proliferative advantage through activation of MEK-ERK signaling (Table S4) (Gyorffy et al., 2012, Labidi-Galy et al., 2015, Clauss et al., 2010, Wei et al., 2012, Williams et al., 2005).

在 HGSOC 队列的 11,134 个癌症特异性 dRE 中,我们重点介绍了恶性部分中癌症特异性基因调控的两个例子。编码肽酶抑制剂 3(Elafin 蛋白)的 PI3 在恶性组分中高度表达,其上调可以用四种癌症特异性 dRE 来解释 ( Data S1 )。PI3 不仅预测浆液性卵巢癌患者的生存率差,还与 OC 化疗耐药有关,并通过激活 MEK-ERK 信号转导赋予 OC 细胞增殖优势 ( Table S4 ) ( Gyorffy et al., 2012 , Labidi-Galy et al., 2015 , Clauss et al., 2010 Wei et al., 2012 Williams et al., 2005 , )。

We also highlight two cancer-specific dREs that were strongly associated with increased LAPTM4B expression in the malignant fraction of the HGSOC patient cohort (Figure 4D). LAPTM4B is predictive of poor survival in OC patients and has been reported as a potent facilitator of chemotherapeutic drug efflux as well as PI3K/AKT signaling (Figure 4E, Table S4) (Li et al., 2010, Tan et al., 2015, Gyorffy et al., 2012). We labeled LAPTM4B cancer-specific dREs as Enhancer 2 (Enh2) and Enhancer 4 (Enh4), and we note that there are three additional dREs annotated within this locus (Enhancer 1, 3, and 5). To interrogate TF occupancy at these dREs, we performed Find Individual Motif Occurrences (FIMO) analysis for each putative enhancer region using the Patient 9 DNA sequence after accounting for single-nucleotide variants in the malignant fraction (subclusters 0-,7-,11-,16-Ovarian cancer) of Patient 9 (Figure 4F and STAR Methods) (Bailey et al., 2015, Grant et al., 2011, Bailey et al., 2009). Interestingly, cells from the Patient 9 malignant fraction harbor a SNP (rs10955131) within Enhancer 2, but we are unable to determine if this mutation is somatically acquired as we did not achieve sufficient read depth in normal immune cells at this particular genomic region to perform variant calling (Figure S17). We observed statistically significant TF motif matches within each putative enhancer region and further ranked them by scRNA-seq TF expression within the Patient 9 malignant fraction (Figure 4F and Table S5). Of note, we found YY1 motifs within Enhancer 2, Enhancer 4 and the LAPTM4B promoter region, suggesting these cancer-specific enhancers participate in active enhancer-promoter connections within malignant cells of Patient 9 (Weintraub et al., 2017).

我们还强调了两种癌症特异性 dREs,它们与 HGSOC 患者队列恶性部分的 LAPTM4B 表达增加密切相关 ( Figure 4D )。LAPTM4B 可预测 OC 患者生存率低,并已被报道为化疗药物外排以及 PI3K/AKT 信号转导的有效促进剂 ( Figure 4E , Table S4 ) ( Li et al., 2010 , Tan et al., 2015 , Gyorffy et al., 2012 )。我们将 LAPTM4B 癌症特异性 dRE 标记为增强子 2 (Enh2) 和增强子 4 (Enh4),我们注意到该基因座内还有三个额外的 dRE 注释 (增强子 1 、 3 和 5)。为了询问这些 dRE 的 TF 占有率,我们在考虑了患者 9 ( Figure 4F 和) Bailey et al., 2015 Grant et al., 2011 Bailey et al., 2009 ( , STAR Methods , ) 的恶性部分(亚簇 0-,7-,11-,16-卵巢癌)中的单核苷酸变异后,使用患者 9 DNA 序列对每个假定的增强子区域进行了查找单个基序出现 (FIMO) 分析).有趣的是,来自患者 9 恶性组分的细胞在增强子 2 中携带 SNP (rs10955131),但我们无法确定这种突变是否是体细胞获得性的,因为我们在这个特定基因组区域的正常免疫细胞中没有达到足够的读取深度来执行变体调用( Figure S17 )。我们在每个推定的增强子区域内观察到具有统计学意义的 TF 基序匹配,并根据患者 9 恶性组分内的 scRNA-seq TF 表达进一步对它们进行排名( Figure 4F 值得注意的是 Table S5). ,我们在增强子 2、增强子 4 和 LAPTM4B 启动子区域中发现了 YY1 基序,表明这些癌症特异性增强子参与患者 9 恶性细胞内的活性增强子-启动子连接 ( Weintraub et al., 2017 )。

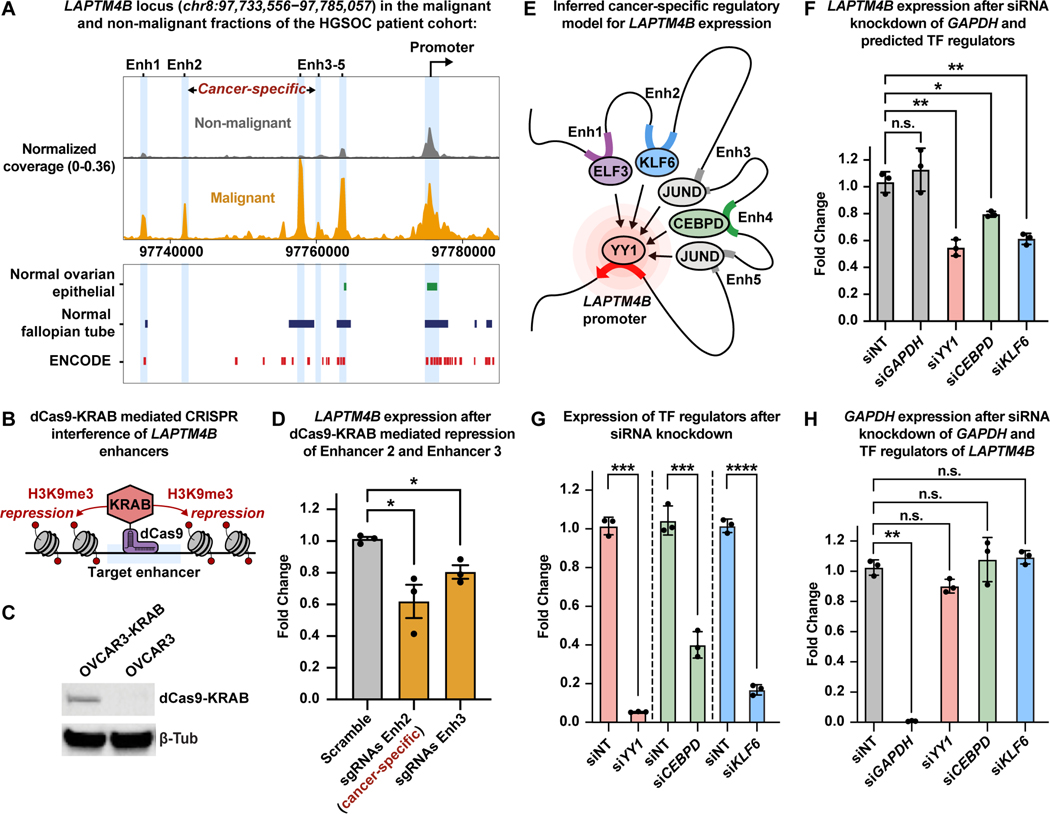

Functional validation of LAPTM4B enhancers and predicted TF regulators

LAPTM4B 增强子和预测的 TF 调节因子的功能验证

To further validate our dRE identification pipeline, we conducted experiments to confirm these dREs and TFs as bona fide enhancers of LAPTM4B expression. First, we used dCas9-KRAB-mediated CRISPR interference assays, in the HGSOC cell line OVCAR3, to inhibit the most highly active cancer-specific dRE (Enhancer 2) and lineage-specific dRE (Enhancer 3) in the LAPTM4B locus (Figure 5A-C and STAR Methods) (Fulco et al., 2016, Larson et al., 2013, Gilbert et al., 2013, Qi et al., 2013). OVCAR3 cells stably expressing dCas9-KRAB were transfected with single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting Enhancer 2 and Enhancer 3 to induce local chromatin repression (Figure 5B and STAR Methods). We then measured the consequences on gene expression and found that LAPTM4B was significantly reduced when targeting Enhancer 2 and Enhancer 3 (Figure 5D). Thus, we conclude that Enhancer 2 and Enhancer 3 are bona-fide enhancers of LAPTM4B, providing support for the remaining dREs identified throughout this study.

为了进一步验证我们的 dRE 鉴定管道,我们进行了实验以确认这些 dREs 和 TFs 是 LAPTM4B 表达的真正增强子。首先,我们在 HGSOC 细胞系 OVCAR3 中使用 dCas9-KRAB 介导的 CRISPR 干扰测定,以抑制 LAPTM4B 位点( Figure 5A - 和 STAR Methods ) ( Fulco et al., 2016 、 C 、 Larson et al., 2013 Gilbert et al., 2013 、 ) Qi et al., 2013 中最活跃的癌症特异性 dRE (Enhancer 2) 和谱系特异性 dRE (Enhancer 3)。用靶向增强子 2 和增强子 3 的单向导 RNA (sgRNA) 转染稳定表达 dCas9-KRAB 的 OVCAR3 细胞,以诱导局部染色质抑制 ( Figure 5B 和 STAR Methods )。然后,我们测量了对基因表达的影响,发现当靶向增强子 2 和增强子 3 时 ,LAPTM4B 显著降低 ( Figure 5D )。因此,我们得出结论,Enhancer 2 和 Enhancer 3 是真正的 LAPTM4B 增强子 , 为本研究中确定的其余 dRE 提供支持。

Figure 5. Functional validation of cancer-specific LAPTM4B regulatory model in high-grade serous ovarian cancer cells.

图 5.高级别浆液性卵巢癌细胞中癌症特异性 LAPTM4B 调节模型的功能验证。

A) Browser track showing the accessibility profile at the LAPTM4B locus, as in Fig. 4D, but between malignant (orange) and non-malignant (gray) fractions of the HGSOC patient cohort. Coverage is normalized by sequencing depth as well as reads in TSS regions. Known regulatory element annotations for normal ovarian surface epithelium, normal fallopian tube, and ENCODE, are shown below the browser track.

A) 浏览器轨迹显示 LAPTM4B 位点的可访问性概况,如 Fig. 4D ,但在 HGSOC 患者队列的恶性( 橙色 )和非恶性( 灰色 )部分之间。通过测序深度以及 TSS 区域的读数对覆盖度进行归一化。正常卵巢表面上皮、正常输卵管和 ENCODE 的已知调节元件注释显示在浏览器轨道下方。

B) Cartoon of dCas9-KRAB mediated CRISPR interference.

B) dCas9-KRAB 介导的 CRISPR 干扰的漫画。

C) Western blot of OVCAR3 cells stably expressing dCas9-KRAB.

C) 稳定表达 dCas9-KRAB 的 OVCAR3 细胞的 Western blot。

D) RT-qPCR results showing expression of LAPTM4B after dCas9-KRAB mediated repression of Enhancer 2 and Enhancer 3. Expression is shown as fold change relative to ACTB expression.

D) RT-qPCR 结果显示 dCas9-KRAB 介导的增强子 2 和增强子 3 抑制后 LAPTM4B 表达。表达表现为相对于 ACTB 表达的倍数变化。

E) Cartoon depicting inferred TF-mediated enhancer-promoter connections.

E) 描绘推断的 TF 介导的增强子-启动子连接的卡通。

F) RT-qPCR results of LAPTM4B expression after siRNA-mediated knockdown of GAPDH and predicted TF regulators: YY1, CEBPD, and KLF6. Expression is shown as fold change relative to ACTB expression.

F) siRNA 介导的 GAPDH 敲低后 LAPTM4B 表达的 RT-qPCR 结果和预测的 TF 调节因子:YY1、CEBPD 和 KLF6。表达表现为相对于 ACTB 表达的倍数变化。

G) RT-qPCR results of expression of TF regulators after siRNA knockdown. Expression is shown as fold change relative to ACTB expression.

G) siRNA 敲低后 TF 调节因子表达的 RT-qPCR 结果。表达表现为相对于 ACTB 表达的倍数变化。

H) RT-qPCR results of expression of GAPDH after siRNA-mediated knockdown of GAPDH and TF regulators. Expression is shown as fold change relative to ACTB expression. Data in D, F, G, and H shown as mean ± S.E.M.; *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001, one-tailed Welch’s t-test.

H) siRNA 介导的 GAPDH 和 TF 调节因子敲低后 GAPDH 表达的 RT-qPCR 结果。表达表现为相对于 ACTB 表达的倍数变化。D、F、G 和 H 中的数据显示为 S.E.M. ±平均值;*p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001, 单尾韦尔奇 t 检验。

We next validated predicted TF regulators of LAPTM4B via RNAi-mediated knockdown in OVCAR3 cells (Figure 5E). We measured the expression of LAPTM4B after knockdown of each predicted TF regulator: YY1, CEBPD, and KLF6. Indeed, we observed a statistically significant decrease in LAPTM4B expression when targeting YY1, CEBPD, and KLF6, but not when targeting the negative control, GAPDH (Figure 5E-H). Thus, YY1, CEBPD, and KLF6 are bona-fide TF regulators of LAPTM4B and provide confidence for our TF predictions (Figure 5E).

接下来,我们通过在 OVCAR3 细胞中通过 RNAi 介导的敲低验证了 LAPTM4B 的预测 TF 调节因子 ( Figure 5E )。我们测量了每种预测的 TF 调节因子 YY1 、 CEBPD 和 KLF6 敲低后 LAPTM4B 的表达。事实上,我们观察到当靶向 YY1、CEBPD 和 KLF6 时,LAPTM4B 表达在统计学上显着降低,但在靶向阴性对照 GAPDH ( Figure 5E - H ) 时没有。因此,YY1、CEBPD 和 KLF6 是真正的 TF 调节因子 LAPTM4B 并为我们的 TF 预测提供了信心 ( Figure 5E )。

Linking dREs to transcription factor activity in human gynecologic malignancies

将 dRE 与人类妇科恶性肿瘤的转录因子活性联系起来

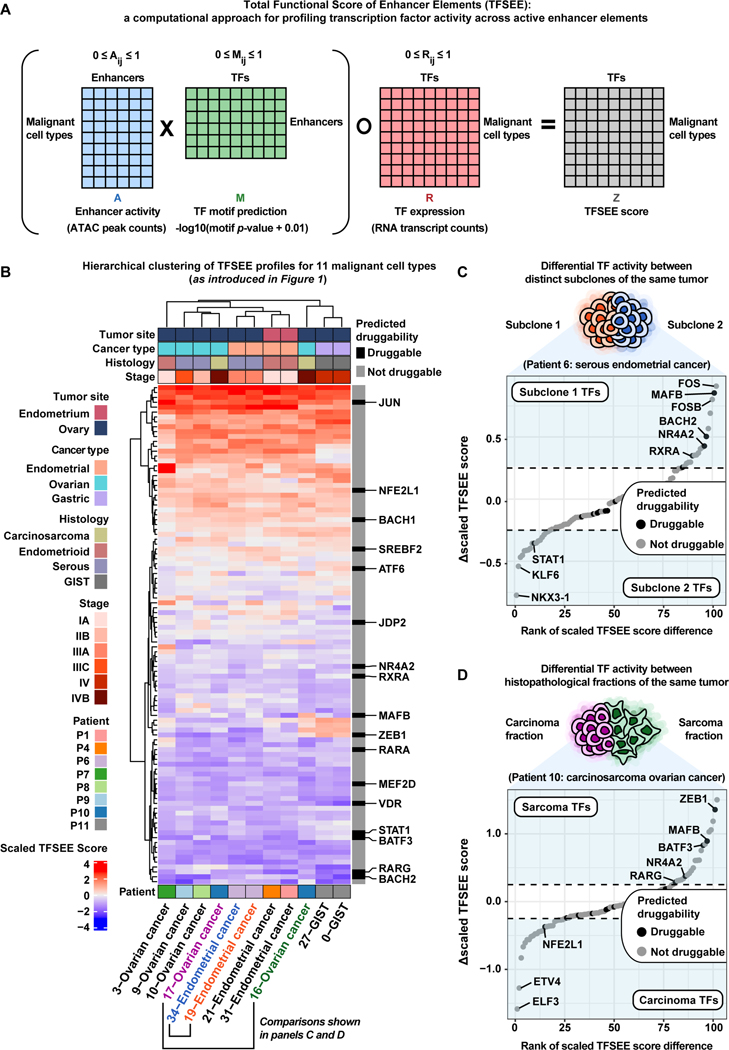

After identifying dREs that may play critical roles in cancer progression, we interrogated trans-acting factors present at these dREs across the entire dataset to better understand the regulatory logic of these tumors. We adapted our published method called Total Functional Score of Enhancer Elements (TFSEE) to predict which TFs are enriched at active dREs (enhancer-like elements) within malignant cell types (Figure 6A, STAR Methods) (Malladi et al., 2020, Franco et al., 2018). By adapting this method to matched scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq, TFSEE allows for concurrent assessment of TF expression, enhancer activity, enhancer location, and TFs present at enhancers. Across the full patient cohort, there were 11 malignant cell type subclusters chosen for TFSEE analysis based on patient specificity, inferred CNV events, and/or cancer biomarker expression patterns (Figure S18). We conducted the TFSEE analysis and observed that the malignant cell types tend to cluster by patient and by cancer type (Figure 6B). To further prioritize enriched TFs across active enhancer elements, we highlighted each TF by its predicted druggability status (binary) as determined by the canSAR database through structure-based and ligand-based assessments (Tym et al., 2016, Mitsopoulos et al., 2020).

在确定了可能在癌症进展中起关键作用的 dRE 后,我们询问了整个数据集中这些 dRE 中存在的反式作用因子,以更好地了解这些肿瘤的调节逻辑。我们采用了我们已发表的称为增强子元件总功能评分 (TFSEE) 的方法,以预测哪些 TF 在恶性细胞类型 ( Figure 6A , STAR Methods ) ( Malladi et al., 2020 , Franco et al., 2018 ) 中的活性 dREs(增强子样元件)处富集。通过将该方法应用于匹配的 scRNA-seq 和 scATAC-seq,TFSEE 允许同时评估 TF 表达、增强子活性、增强子位置和增强子处存在的 TF。在整个患者队列中,根据患者特异性、推断的 CNV 事件和/或癌症生物标志物表达模式选择了 11 个恶性细胞类型亚集群进行 TFSEE 分析 ( Figure S18 )。我们进行了 TFSEE 分析并观察到恶性细胞类型倾向于按患者和癌症类型 ( Figure 6B ) 聚集。为了进一步优先考虑活性增强子元件中富集的 TF,我们通过其预测的成药性状态(二进制)突出显示每个 TF,该状态由 canSAR 数据库通过基于结构和基于配体的评估确定 ( Tym et al., 2016 , Mitsopoulos et al., 2020 )。

Figure 6. Functional scoring of cell type-specific enhancer activity and their cognate transcription factors helps prioritize potential therapeutic targets across gynecologic malignancies.

图 6.细胞类型特异性增强子活性及其同源转录因子的功能评分有助于优先考虑妇科恶性肿瘤的潜在治疗靶点。

A) Cartoon of matrix operations performed in the Total Functional Score of Enhancer Elements (TFSEE) method. Only malignant cell type clusters with 100% patient specificity were chosen for TFSEE analysis.

A) 在增强子元件总功能评分 (TFSEE) 方法中执行的矩阵运算的漫画。仅选择具有 100% 患者特异性的恶性细胞类型簇进行 TFSEE 分析。

B) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering heatmap of cell type normalized TFSEE scores (n=102 TFs across active enhancers). Each row of the heatmap represents TF activity across cell type-specific enhancers enriched in each column. Predicted druggability status for each TF is marked with druggable/not druggable according to the canSAR database.

B) 细胞类型归一化 TFSEE 分数的无监督分层聚类热图(活性增强子中的 n=102 个 TF)。热图的每一行都表示每列中富集的细胞类型特异性增强子的 TF 活性。根据 canSAR 数据库,每个 TF 的预测成药性状态标记为 Druggable/Not Druggable。

C) Rank-ordered plot showing the difference in scaled TFSEE score for each TF between subclone 1 (orange) and subclone 2 (blue) of the Patient 6 tumor representing serous EC. Each point represents a TF and is colored by predicted druggability status. Notable TFs enriched in either condition (subclone 1/subclone 2) are labeled in light blue regions of the plot.

C) 排序图显示了代表浆液性 EC 的患者 6 肿瘤的亚克隆 1( 橙色 )和亚克隆 2( 蓝色 )之间每个 TF 的缩放 TFSEE 评分的差异。每个点代表一个 TF,并按预测的成药性状态着色。在任一条件(亚克隆 1/亚克隆 2)中富集的显着 TF 都标记在图的浅蓝色区域中。

D) Rank-ordered plot showing the difference in scaled TFSEE score for each TF between carcinoma (pink) and sarcoma (green) fractions of the Patient 10 tumor representing carcinosarcoma OC. Each point represents a TF and is colored by predicted druggability status. Notable TFs enriched in either condition (sarcoma/carcinoma) are labeled in light blue regions of the plot.

D) 排序图显示了代表癌肉瘤 OC 的患者 10 肿瘤的癌( 粉红色 )和肉瘤( 绿色 )部分之间每个 TF 的缩放 TFSEE 评分的差异。每个点代表一个 TF,并按预测的成药性状态着色。在任一情况 (肉瘤/癌) 中富集的显着 TF 都标记在图的浅蓝色区域。

To exemplify the utility of TFSEE with single-cell data, we investigated intratumoral heterogeneity of two patients with rare histological subtypes. For Patient 6, diagnosed as EC of serous histology that metastasized to the ovary, there were two distinct tumor subclones (19- and 34-Endometrial cancer) highlighted by their distinct CNV profiles (Figure 6C, Figure S2, Table 1, Table S1). We visualized the differences in TF activity between these two subclones and observed several notable TFs enriched in each subclone (Figure 6C). Of note, we found MAFB to be enriched in the 19-Endometrial cancer subclone of the Patient 6 tumor relative to the 34-Endometrial cancer subclone. Moreover, MAFB is predicted to be druggable by ligand-based assessment according to the canSAR database (Mitsopoulos et al., 2020, Tym et al., 2016). We also observed STAT1 is enriched in the 34-Endometrial cancer subclone of the Patient 6 tumor (Mitsopoulos et al., 2020, Tym et al., 2016). These differences in TF activity may provide valuable insight into intratumoral heterogeneity of serous EC.

为了用单细胞数据举例说明 TFSEE 的效用,我们调查了两名罕见组织学亚型患者的瘤内异质性。对于患者 6,诊断为转移至卵巢的浆液性组织学 EC,有两个不同的肿瘤亚克隆(19 和 34 子宫内膜癌),由其不同的 CNV 谱 ( Figure 6C 、 Figure S2 、 Table 1 、 Table S1 )突出显示。我们可视化了这两个亚克隆之间 TF 活性的差异,并观察到每个亚克隆中富集的几个显着 TF ( Figure 6C )。值得注意的是,我们发现 MAFB 相对于 34 个子宫内膜癌亚克隆,在患者 6 肿瘤的 19 个子宫内膜癌亚克隆中富集。此外,根据 canSAR 数据库 ( Mitsopoulos et al., 2020 , Tym et al., 2016 ),通过基于配体的评估预测 MAFB 是可成药的。我们还观察到 STAT1 在患者 6 肿瘤的 34 个子宫内膜癌亚克隆中富集 ( Mitsopoulos et al., 2020 , Tym et al., 2016 )。TF 活性的这些差异可能为浆液性 EC 的瘤内异质性提供有价值的见解。

We also chose to investigate the two histopathological fractions (16- and 17-Ovarian cancer) of the Patient 10 tumor diagnosed as an ovarian carcinosarcoma (Table 1, Table S1). While these two histopathological fractions have similar inferred CNV profiles, a pseudo-bulk gene-set variation analysis (GSVA) across all malignant cell types revealed a higher enrichment of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and Invasion gene signatures within the 16-Ovarian cancer subcluster (Figures S3 and S18). This suggests the 16-Ovarian cancer subcluster represents the sarcoma fraction while the 17-Ovarian cancer subcluster represents the carcinoma fraction. These fraction identity assignments are also supported by clustering of 16-Ovarian cancer with the GIST subclusters, 0-/27-GIST, and clustering of 17-Ovarian cancer with the HGSOC subclusters, 9-/10-Ovarian cancer (Figure 6B). To uncover differences in TF activity between the carcinoma fraction (17-Ovarian cancer) and sarcoma fraction (16-Ovarian cancer) of the Patient 10 tumor, we visualized the differences in scaled TFSEE score and identified a number of TFs enriched in each fraction. ZEB1 was enriched in the sarcoma fraction relative to carcinoma fraction (Figure 6D) (Mitsopoulos et al., 2020, Tym et al., 2016). This result is in line with ZEB1’s role in EMT and repression of epithelial-specific genes (Sánchez-Tilló et al., 2011, Watanabe et al., 2019). We also observed the epithelial-specific transcription factor ELF3 enriched in the carcinoma fraction relative to the sarcoma fraction (Figure 6D) (Sengez et al., 2019, Brembeck et al., 2000). These distinct TF activity profiles, along with the shared inferred CNV events between the histopathological fractions of the ovarian carcinosarcoma, may help researchers and clinicians better understand the etiologyof gynecologic carcinosarcomas (Barker and Scott, 2020, Kostov et al., 2020).

我们还选择调查诊断为卵巢癌肉瘤 ( Table 1 , Table S1 ) 的患者 10 肿瘤的两个组织病理学部分(16 和 17 卵巢癌)。虽然这两个组织病理学部分具有相似的推断 CNV 谱,但所有恶性细胞类型的伪大量基因集变异分析 (GSVA) 显示,在 16 个卵巢癌亚簇内, 上皮-间质转化 (EMT) 和侵袭基因特征的富集程度更高( Figures S3 和 S18 ).这表明 16 个卵巢癌子簇代表肉瘤分数,而 17 个卵巢癌子簇代表癌分数。16 卵巢癌与 GIST 子簇 0-/27-GIST 的聚类以及 17 卵巢癌与 HGSOC 亚簇 9-/10-卵巢癌的聚类也支持这些分数同一性分配 ( Figure 6B )。为了揭示患者 10 肿瘤的癌分数 (17-卵巢癌) 和肉瘤分数 (16-卵巢癌) 之间 TF 活性的差异,我们可视化了缩放 TFSEE 评分的差异,并确定了每个分数中富集的许多 TF。ZEB1 在肉瘤组分中富集,相对于癌组分 ( Figure 6D ) ( Mitsopoulos et al., 2020 , Tym et al., 2016 )。该结果与 ZEB1 在 EMT 和抑制上皮特异性基因中的作用一致 ( Sánchez-Tilló et al., 2011 , Watanabe et al., 2019 )。我们还观察到相对于肉瘤分数 ( Figure 6D ) ( Sengez et al., 2019 , Brembeck et al., 2000 ) 的癌症分数中富集的上皮特异性转录因子 ELF3 。 这些不同的 TF 活动概况,以及卵巢癌肉瘤组织病理学部分之间共享的推断 CNV 事件,可能有助于研究人员和临床医生更好地了解妇科癌肉瘤的病因 ( Barker and Scott, 2020 , Kostov et al., 2020 )。

Our TFSEE analysis allowed us to make additional comparisons of serous versus endometrioid OC, serous versus endometrioid EC, and GIST versus serous OC (Figure S19). In each case, we identify important TF regulators enriched in either histologic type. Of note, we observed RARG enriched in serous OC relative to endometrioid OC, MAFB enriched in serous EC relative to endometrioid EC, and ZEB1 enriched in GIST relative to serous OC (Figure S19B-D). Overall, our TFSEE analysis is a novel framework in single-cell genomics that reveals robust inferences of TF activity coupled to TF expression. This strategy attempts to lower the false positive rate of motif-based TF predictions by enriching for TFs with non-zero expression and giving lower weight to TFs with zero or negligible expression. In some instances, some TFs can still be functional without being actively transcribed. Therefore, we chose to explore an alternate version of the TFSEE analysis that is agnostic to TF expression by omitting the last element-wise multiplication with the TF expression matrix and found similar results (Figure S20).

我们的 TFSEE 分析使我们能够对浆液性与子宫内膜样 OC、浆液性与子宫内膜样 EC 以及 GIST 与浆液性 OC 进行额外的比较 ( Figure S19 )。在每种情况下,我们都会确定在任一组织学类型中富集的重要 TF 调节因子。值得注意的是,我们观察到相对于子宫内膜样 OC 富含浆液性 OC 的 RARG,相对于子宫内膜样 EC 富含浆液性 EC 的 MAFB,以及相对于浆液性 OC 富含 GIST 的 ZEB1 ( Figure S19B - D )。总体而言,我们的 TFSEE 分析是单细胞基因组学中的一个新框架,它揭示了 TF 活性与 TF 表达偶联的稳健推断。该策略试图通过富集非零表达的 TF 并降低表达为零或可忽略不计的 TF 的权重来降低基于基序的 TF 预测的假阳性率。在某些情况下,某些 TF 仍然可以正常工作,而无需主动转录。因此,我们选择通过省略与 TF 表达式矩阵的最后一个元素乘法来探索与 TF 表达式无关的 TFSEE 分析的替代版本,并发现了类似的结果 ( Figure S20 )。

DISCUSSION 讨论

To date, the standard of care for OC and EC is a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. Despite these aggressive treatments, most women with advanced stage EC and OC will succumb to their disease, highlighting the need to develop better targeted therapies. Our work represents a valuable multi-omic resource that charts the transcriptional and regulatory landscape of gynecologic tumors at single-cell resolution. Deconvolution of this dataset identified novel mechanisms that facilitate tumorigenesis and prioritized potential avenues for therapeutic intervention that were hidden using bulk genomic approaches. We also shed light on non-coding regulatory mechanisms for a number of clinically relevant biomarkers and major playersinvolved in cancer pathogenesis (Yang et al., 2017, Duffy et al., 2005, Dong et al., 2017, Sturgeon et al., 2008, Sarlomo-Rikala et al., 1998). Moreover, we anticipate that this dataset will help inspire novel therapeutic treatment strategies in EC and/or OC by serving as a reference for 1) clinicians in understanding intratumoral heterogeneity, 2) hypothesis generation in cancer biology, 3) cell type annotation in future single-cell datasets, and 4) the development of novel bioinformatic methods.

迄今为止,OC 和 EC 的标准护理是手术、化疗和放疗相结合。尽管接受了这些积极的治疗,但大多数患有晚期 EC 和 OC 的女性会死于疾病,这凸显了开发更好的靶向疗法的必要性。我们的工作代表了一种有价值的多组学资源,它以单细胞分辨率绘制了妇科肿瘤的转录和调节景观。该数据集的反卷积确定了促进肿瘤发生的新机制,并优先考虑了使用批量基因组方法隐藏的治疗干预的潜在途径。我们还阐明了许多临床相关生物标志物和参与癌症发病机制的主要参与者的非编码调节机制 ( Yang et al., 2017 、 、 Duffy et al., 2005 Dong et al., 2017 、 Sturgeon et al., 2008 Sarlomo-Rikala et al., 1998 、 )。此外,我们预计该数据集将作为 1) 临床医生了解肿瘤内异质性的参考,2) 癌症生物学中的假设生成,3) 未来单细胞数据集中的细胞类型注释,以及 4) 新型生物信息学方法的开发。

We reiterate four important findings from analyzing this single-cell dataset. First, we demonstrated that cancer cells acquire de novo non-coding dREs that modulate hallmark cancer pathways, including mTOR signaling, in a cancer-specific manner (Figures 2–5, Data S1). This is consistent with recent clinical trials testing mTOR inhibitors in combination therapy for ovarian cancer patients (Das et al., 2017, Westin, 2014, Banerji, 2014). From this, we speculate that the mTOR-enriched Patient 7 may benefit from an mTOR inhibitor treatment, although further investigation is needed. Nonetheless, these data demonstrate important non-coding mechanisms for how cancer cells may acquire aggressive phenotypes due to changes in chromatin accessibility and TF occupancy.

我们重申了分析该单细胞数据集的四个重要发现。首先,我们证明癌细胞以癌症特异性方式获得从头非编码 dRE,这些 dRE 调节标志性癌症通路,包括 mTOR 信号传导 ( Figures 2 – 5 , Data S1 )。这与最近在卵巢癌患者联合治疗中测试 mTOR 抑制剂的临床试验一致 ( Das et al., 2017 , Westin, 2014 , Banerji, 2014 )。由此,我们推测富含 mTOR 的患者 7 可能受益于 mTOR 抑制剂治疗,尽管需要进一步研究。尽管如此,这些数据证明了癌细胞如何由于染色质可及性和 TF 占有率的变化而获得侵袭性表型的重要非编码机制。

Moreover, cancer-specific dREs identified in each analysis cohort linked to more target genes on average compared to the lineage-specific dREs (Figure 2D). Based on our data, we anticipate this trend to be even greater across a larger group of patient tumors and posit that salient cancer-specific dREs carry a higher ‘regulatory load’ relative to dREs active in normal tissues. This could be explained by alterations in topologically associating domain boundaries and higher order chromatin structure, but this warrants further investigation (Akdemir et al., 2020).

此外,与谱系特异性 dRE 相比,每个分析队列中鉴定的癌症特异性 dRE 平均与更多的靶基因相关 ( Figure 2D )。根据我们的数据,我们预计这种趋势在更大的患者肿瘤群体中会更大,并假设相对于在正常组织中活跃的 dRE,显着的癌症特异性 dRE 具有更高的“调节负荷”。这可以通过拓扑关联结构域边界和高阶染色质结构的改变来解释,但这值得进一步研究 ( Akdemir et al., 2020 )。

Next, malignant populations within and between patient tumors show substantial heterogeneity in chromatin accessibility linked to transcriptional output (Figures 1–6). This poses a challenging obstacle in EC and OC treatment, and highlights the importance of intratumoral heterogeneity and the growing need for more single-cell datasets of solid tumors, especially in response to chemotherapy. The extent to which malignant cell populations can be described as distinct ‘cell types’ or ‘cell states’ remains elusive and inspires further study into temporally regulated oncogenic regulatory elements and lineage tracing of malignant cell populations (Clevers et al., 2017).

接下来,患者肿瘤内和患者肿瘤之间的恶性群体在与转录输出相关的染色质可及性方面显示出很大的异质性 ( Figures 1 – 6 )。这给 EC 和 OC 治疗带来了具有挑战性的障碍,并凸显了瘤内异质性的重要性以及对更多实体瘤单细胞数据集的需求不断增长,尤其是在对化疗的反应方面。恶性细胞群在多大程度上可以被描述为不同的“细胞类型”或“细胞状态”仍然难以捉摸,并激发了对时间调节的致癌调节元件和恶性细胞群的谱系追踪的进一步研究 ( Clevers et al., 2017 )。

Lastly, our methodology to infer differential TF activity between populations of malignant cells reveals another complex layer of gene regulation that is repurposed in cancer cells (Figure 6 and Figures S19-S20). Our TFSEE analysis is a powerful tool that facilitates integration of scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq datasets to interrogate complex mechanisms of gene regulation. This helps prioritize TFs for follow up investigation and could help inspire novel therapeutic avenues in gynecologic malignancies. As a whole, this resource showcases important principles of gene regulation and tumor biology determined through single-cell multi-omic data.

最后,我们推断恶性细胞群之间差异 TF 活性的方法揭示了另一个复杂的基因调控层,该层在癌细胞中被重新利用 ( Figure 6 和 Figures S19 - S20 )。我们的 TFSEE 分析是一个强大的工具,可促进 scRNA-seq 和 scATAC-seq 数据集的集成,以询问基因调控的复杂机制。这有助于确定 TF 的优先级以进行后续调查,并可能有助于激发妇科恶性肿瘤的新治疗途径。总体而言,该资源展示了通过单细胞多组学数据确定的基因调控和肿瘤生物学的重要原理。

Limitations of study 研究的局限性

We recognize the true richness of the dataset cannot be exemplified here in full, and that there are some limitations associated with our approach. First, scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq libraries were prepared for each tumor by independent sampling of the cell suspension generated for each tumor. While Seurat v3 allows for robust alignment of cell types across datasets, there are methods for profiling the transcriptome and chromatin landscape within the same cell (Cao et al., 2018, Chen et al., 2019, Ma et al., 2020). However, these methods have yet to become widely accessible and come with their own set of technical nuances. Secondly, the number of cell type subclusters identified in the scRNA-seq data is dependent on user-defined parameters such as number of PCs and clustering resolution (Xu and Su, 2015, Stuart et al., 2019). While we did not explore all possible parameter sets, we note that characterizing cell type composition of each tumor was not the main focus of our study. Therefore, there may be even more complexity in these single-cell data. Thirdly, we realize that our Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were derived from bulk measurements in contrast to our single-cell data. Finally, we acknowledge that our study was limited by a small number of patients with a mix of histotypes which could affect the generalizability of our resource. However, we note that our requirement for treatment-naïve tumors prevented us from being more selective in regard to tumor histology. All patient specimens presented are treatment-naïve tumors, which are difficult to procure since the standard of care for HGSOC is shifting towards neo-adjuvant treatment. Nonetheless, these data and the analyses described herein represent a true baseline for these cancers, serving as a foundation for defining the regulatory logic of malignant cells at single-cell resolution.

我们认识到数据集的真正丰富性无法在这里完整地举例说明,而且我们的方法存在一些局限性。首先,通过对每个肿瘤生成的细胞悬液进行独立采样,为每个肿瘤制备 scRNA-seq 和 scATAC-seq 文库。虽然 Seurat v3 允许跨数据集的细胞类型稳健对齐,但有一些方法可以分析同一细胞内的转录组和染色质景观 ( Cao et al., 2018 , Chen et al., 2019 Ma et al., 2020 , )。然而,这些方法尚未得到广泛使用,并且具有自己的一系列技术细微差别。其次,在 scRNA-seq 数据中鉴定的细胞类型子簇的数量取决于用户定义的参数,例如 PC 数量和聚类分辨率 ( Xu and Su, 2015 , Stuart et al., 2019 )。虽然我们没有探索所有可能的参数集,但我们注意到表征每种肿瘤的细胞类型组成并不是我们研究的主要重点。因此,这些单单元数据可能会更加复杂。第三,我们意识到我们的 Kaplan-Meier 生存分析是从批量测量中得出的,与我们的单细胞数据相比。最后,我们承认我们的研究受到少数具有混合组织型的患者的限制,这可能会影响我们资源的普遍性。然而,我们注意到,我们对初治肿瘤的要求使我们在肿瘤组织学方面更具选择性。提供的所有患者标本都是未接受过治疗的肿瘤,由于 HGSOC 的护理标准正在转向新辅助治疗,因此很难获得。 尽管如此,这些数据和本文描述的分析代表了这些癌症的真实基线,是定义单细胞分辨率下恶性细胞的调节逻辑的基础。

STAR METHODS STAR 方法

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY 资源可用性

Lead Contact 牵头联系人

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Hector L. Franco (hfranco@med.unc.edu).

更多信息以及资源和试剂请求应直接发送至牵头联系人 Hector L. Franco (hfranco@med.unc.edu) 并由其完成。

Materials availability 材料可用性

Plasmids generated in this study are available upon request.

本研究中生成的质粒可应要求提供。

Data and code availability

数据和代码可用性

Processed single-cell RNA-seq data and single-cell ATAC-seq have been deposited at GEO(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the accession number GSE173682 and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Raw data (10x FASTQs) will be available with controlled access via dbGAP under the accession number phs002340.v1.p1 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap/).

处理后的单细胞 RNA-seq 数据和单细胞 ATAC-seq 已存放在 GEO( https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ ) 的登录号 GSE173682 下,并在发布之日公开可用。原始数据 (10x FASTQ) 将通过 dbGAP 在登录号 phs002340.v1.p1 ( ) 下通过受控访问提供 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap/ 。All original code has been deposited on the Zenodo platform (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5546110) and is publicly available at the Github repository scENDO_scOVAR_2020 (https://github.com/RegnerM2015/scENDO_scOVAR_2020).

所有原始代码均已存放在 Zenodo 平台上 (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5546110),并在 Github 存储库 scENDO_scOVAR_2020 ( https://github.com/RegnerM2015/scENDO_scOVAR_2020 ) 中公开提供。Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact (hfranco@med.unc.edu).

重新分析本文中报告的数据所需的任何其他信息均可从潜在客户联系人 (hfranco@med.unc.edu) 处获得。

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

实验模型和主题详细信息

Human Patient Samples and Tumor Dissociation

人类患者样本和肿瘤解离