Abstract 摘要

Neuroinflammation plays a crucial role in traumatic brain injury (TBI), contributing to both damage and recovery, yet no effective therapy exists to mitigate central nervous system (CNS) injury and promote recovery after TBI. In the present study, we found that nasal administration of an anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody ameliorated CNS damage and behavioral deficits in a mouse model of contusional TBI. Nasal anti-CD3 induced a population of interleukin (IL)-10-producing regulatory T cells (Treg cells) that migrated to the brain and closely contacted microglia. Treg cells directly reduced chronic microglia inflammation and regulated their phagocytic function in an IL-10-dependent manner. Blocking the IL-10 receptor globally or specifically on microglia in vivo abrogated the beneficial effects of nasal anti-CD3. However, the adoptive transfer of IL-10-producing Treg cells to TBI-injured mice restored these beneficial effects by enhancing microglial phagocytic capacity and reducing microglia-induced neuroinflammation. These findings suggest that nasal anti-CD3 represents a promising new therapeutic approach for treating TBI and potentially other forms of acute brain injury.

神经炎症在创伤性脑损伤(TBI)中起关键作用,既参与损伤过程也影响恢复进程,但目前尚无有效疗法能减轻中枢神经系统(CNS)损伤并促进 TBI 后恢复。本研究发现,在脑挫伤 TBI 小鼠模型中,鼻腔给予抗 CD3 单克隆抗体可改善 CNS 损伤和行为缺陷。鼻腔抗 CD3 治疗诱导产生了一群分泌白细胞介素(IL)-10 的调节性 T 细胞(T reg 细胞),这些细胞迁移至脑部并与小胶质细胞密切接触。T reg 细胞通过 IL-10 依赖性方式直接减轻慢性小胶质细胞炎症并调节其吞噬功能。在体内全局性或特异性阻断小胶质细胞的 IL-10 受体后,鼻腔抗 CD3 的治疗效果被消除。而将分泌 IL-10 的 T reg 细胞过继转移至 TBI 损伤小鼠体内,则通过增强小胶质细胞吞噬能力和减轻小胶质细胞介导的神经炎症,恢复了这些有益效应。这些发现表明鼻腔抗 CD3 疗法为治疗 TBI 及其他急性脑损伤提供了潜在的新型治疗策略。

Subject terms: Neuroimmunology, Inflammation, Microglia

主题词:神经免疫学、炎症、小胶质细胞

Nasal anti-CD3 therapy shows promise for treating traumatic brain injury by reducing neuroinflammation and aiding recovery in mice. It induces interleukin-10-producing regulatory T cells that enhance microglial phagocytic activity and reduce chronic inflammation, potentially aiding brain repair.

鼻腔抗 CD3 疗法通过减轻神经炎症和促进小鼠恢复,显示出治疗创伤性脑损伤的潜力。该疗法能诱导产生白细胞介素-10 的调节性 T 细胞,从而增强小胶质细胞的吞噬活性并减少慢性炎症,可能有助于脑部修复。

Main 主要

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of death and disability, with both direct and indirect costs1–3. TBI is implicated in long-term morbidity, including motor deficits, cognitive decline and long-term medical comorbidities and neurodegeneration4–6. Current treatments primarily focus on early surgical intervention to limit hematoma expansion and supportive therapy; however, there are few pharmacological interventions to reduce long-term cognitive sequelae post-injury7–10. TBI induces a primary mechanical injury followed by a secondary biochemical and cellular response which contributes to neurological impairment11. Critically, neuroinflammation is one of the key mechanisms implicated in both the acute and the chronic phases of TBI12 and, as such, has been identified as an important and potentially modifiable driver of secondary injury in both animal and human studies13–19. TBI drives secondary injury via the activation of resident microglia, induction of cytokine release and recruitment of circulating monocytes or lymphocytes to the CNS, which further amplifies pathological inflammation11,20. Despite the clear clinical implications, no treatment specifically targets this neuroinflammatory process, partly as the result of the largely unknown molecular and cellular mechanisms that lead to neurological deficits after TBI20,21. Therefore, identifying new therapies to address chronic CNS inflammation after TBI represents an important unmet need.

创伤性脑损伤(TBI)是导致死亡和残疾的主要原因,会产生直接和间接成本 1–3 。TBI 与长期发病率相关,包括运动功能障碍、认知能力下降以及长期医学共病和神经退行性变 4–6 。当前的治疗主要侧重于通过早期手术干预限制血肿扩大和支持性治疗;然而,能减少损伤后长期认知后遗症的药物治疗手段十分有限 7–10 。TBI 首先引发原发性机械损伤,继而产生继发性生化和细胞反应,从而导致神经功能缺损 11 。关键的是,神经炎症是 TBI 急性和慢性阶段的关键机制之一 12 ,因此动物和人类研究均将其确定为继发性损伤的重要且具有潜在可调控性的驱动因素 13–19 。TBI 通过激活驻留小胶质细胞、诱导细胞因子释放以及招募循环单核细胞或淋巴细胞进入中枢神经系统,从而加剧病理性炎症反应,驱动继发性损伤 11,20 。 尽管其临床意义明确,但目前尚无专门针对这一神经炎症过程的治疗方法,部分原因是导致 TBI 后神经功能缺损的分子和细胞机制在很大程度上仍属未知 20,21 。因此,开发针对 TBI 后慢性中枢神经系统炎症的新疗法,是一项亟待满足的重要临床需求。

FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Treg cells) represent a crucial subset of CD4+ T cells that modulate and limit adherent inflammatory responses22. There is a growing body of evidence showing that FoxP3+ Treg cells play a critical role in maintaining immune homeostasis and suppressing immune responses in several acute23,24 and chronic neurological diseases25,26. Experimentally, the depletion of FoxP3+ Treg cells in mice with controlled cortical impact (CCI) injuries leads to increased T cell infiltration, enhanced reactive astrogliosis and exacerbated motor deficits27. Conversely, expanding CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells through IL-2 treatment has been shown to improve outcomes in animal models of TBI28. In humans with TBI, the level of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells positively correlates with clinical outcomes29. Together, these studies suggest that inducing Treg cells is a promising approach for the treatment of TBI.

FoxP3+调节性 T 细胞(Treg 细胞)是 CD4+ T 细胞中至关重要的亚群,能够调节和限制持续性炎症反应。越来越多的证据表明,FoxP3+ Treg 细胞在维持免疫稳态和抑制多种急性及慢性神经系统疾病的免疫反应中发挥关键作用。实验研究表明,在控制性皮质撞击(CCI)损伤小鼠中清除 FoxP3+ Treg 细胞会导致 T 细胞浸润增加、反应性星形胶质细胞增生加剧以及运动功能障碍恶化。相反,通过 IL-2 治疗扩增 CD4+FoxP3+ Treg 细胞可改善 TBI 动物模型的预后。在人类 TBI 患者中,CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg 细胞水平与临床预后呈正相关。这些研究共同表明,诱导 Treg 细胞是治疗 TBI 的一种有前景的方法。

The mucosal immune system is a unique tolerogenic organ that provides a physiological method for inducing Treg cells and is clinically appealing as a result of its apparent lack of toxicity. Our laboratory has investigated the induction of Treg cells by the nasal administration of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (aCD3 mAb) and has shown the ameliorating effects of nasal aCD3 in both autoimmune30 and CNS models of disease, including models of progressive multiple sclerosis (MS)31 and Alzheimer’s disease32. Based on this, we investigated whether nasal aCD3 could influence outcomes in relevant TBI models by modulating both systemic and local CNS immune responses.

黏膜免疫系统是一种独特的免疫耐受器官,可通过生理性方式诱导调节性 T 细胞(Treg),且因其明显无毒性而在临床上备受关注。我们实验室通过鼻腔给予抗 CD3 单克隆抗体(aCD3 mAb)诱导 Treg 细胞,并证实鼻腔给予 aCD3 在自身免疫性疾病和中枢神经系统疾病模型(包括进展型多发性硬化症(MS)和阿尔茨海默病模型)中均具有改善作用。基于此,我们研究了鼻腔给予 aCD3 是否可通过调节全身及局部中枢神经系统免疫反应来影响创伤性脑损伤(TBI)模型的预后。

Accordingly, we demonstrated that nasal aCD3 induces FoxP3+ Treg cells, which ameliorate TBI by modulating CNS innate immunity, enhancing microglia phagocytosis and improving neuropathological and behavioral outcomes post-injury in an IL-10-dependent manner. These findings highlight a new immune-based approach for treating TBI and potentially other types of acute brain injury.

因此,我们证实鼻内给予 aCD3 抗体可诱导 FoxP3 + T reg 细胞,这些细胞通过调节中枢神经系统先天免疫、增强小胶质细胞吞噬功能并以 IL-10 依赖性方式改善损伤后的神经病理学和行为学结局,从而缓解创伤性脑损伤。该研究结果揭示了一种治疗 TBI 及潜在其他类型急性脑损伤的新型免疫疗法。

Results 结果

Nasal aCD3 mAb improves cognitive and motor outcomes after TBI

鼻腔抗 CD3 单克隆抗体可改善创伤性脑损伤后的认知和运动功能

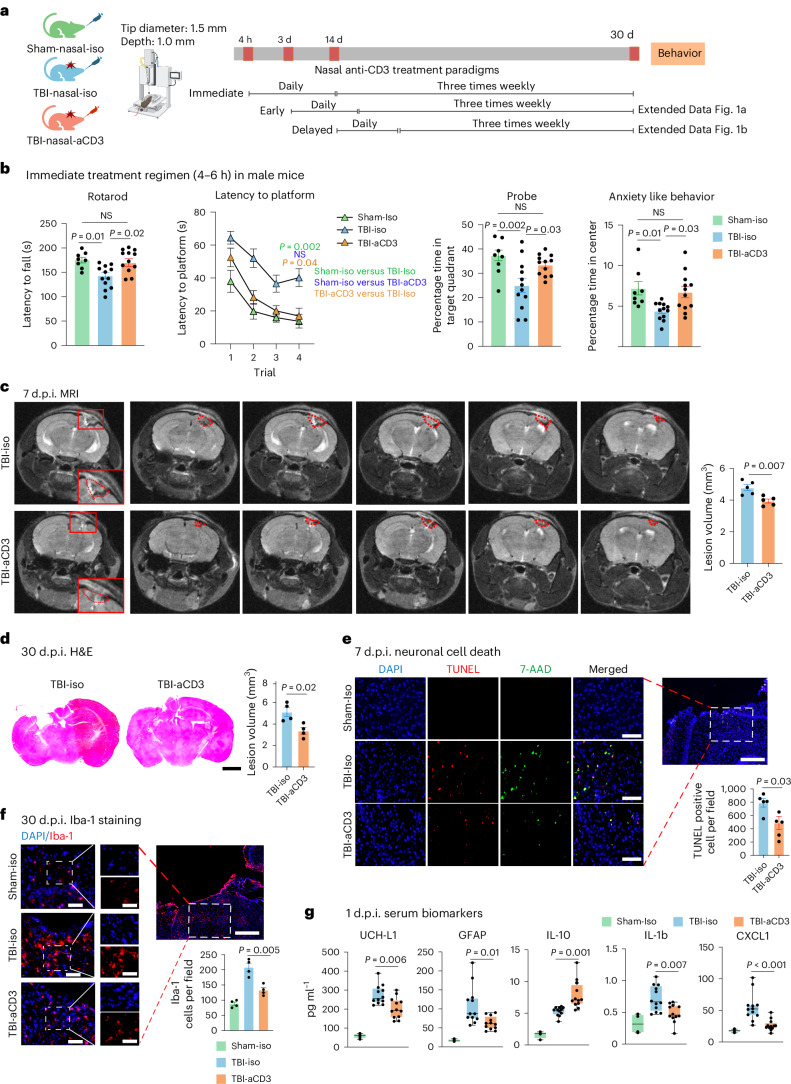

To investigate the therapeutic effect of nasal aCD3 in TBI, we employed the CCI model of TBI, which is known for its accuracy and reproducibility33, to recapitulate features of moderate-to-severe TBI features, including cerebral contusion, neuroinflammation, blood–brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction and long-term behavioral outcomes. We investigated the therapeutic effects of nasal aCD3 on motor and behavioral outcomes in male mice treated at different times after injury: immediate (4-6 h post-injury), early (3 d post-injury) and delayed (14 d post-injury) (Fig. 1a). Treatment was continued once daily for 7 d, then 3× weekly for up to 1 month after injury (Fig. 1a). In the immediate treatment group, we found improvement in motor function and coordination assessed by the rotarod test (Fig. 1b). Using the Morris water maze (MWM) test, TBI mice treated with aCD3 exhibited near-complete restoration of spatial memory and increased time spent in the target quadrant during the probe trial (Fig. 1b) compared with isotype-treated TBI mice. In addition, we found that male mice treated with immediate nasal aCD3 exhibited less anxious behavior, using the open field test. We found a similar beneficial effect with early treatment (3 d post-injury), except for anxiety (Extended Data Fig. 1a).

为探究鼻腔给予 aCD3 对创伤性脑损伤(TBI)的治疗效果,我们采用具有高度准确性和可重复性的 CCI 模型 33 来模拟中重度 TBI 特征,包括脑挫伤、神经炎症、血脑屏障(BBB)功能障碍及长期行为学改变。我们研究了不同时间窗(伤后立即[4-6 小时]、早期[3 天]和延迟期[14 天])给予鼻腔 aCD3 对雄性小鼠运动及行为学结局的影响(图 1a )。治疗方案为每日 1 次连续 7 天,之后每周 3 次持续至伤后 1 个月(图 1a )。在立即治疗组中,通过转棒测试发现运动功能和协调性改善(图 1b )。Morris 水迷宫(MWM)测试显示,与同型对照处理的 TBI 小鼠相比,aCD3 治疗组小鼠的空间记忆能力接近完全恢复,且在探测试验中目标象限停留时间显著延长(图 1b )。此外,通过旷场实验发现,立即鼻腔给予 aCD3 的雄性小鼠表现出更少的焦虑行为。 我们发现早期治疗(伤后 3 天)具有类似的有益效果,但焦虑症状除外(扩展数据图 1a )。

Fig. 1. Nasal aCD3 improves behavioral outcomes and ameliorates neuropathological outcomes in the CCI model of TBI.

图 1. 鼻腔给予 aCD3 改善 CCI 创伤性脑损伤模型的行为学结果并减轻神经病理学损伤

a, Experimental timeline schematic for treatment regimens (created with BioRender.com). b, Behavioral testing (rotarod, MWM test, probe trial, open field for anxiety-like behavior) in the immediate treatment group (sham-iso n = 8, TBI-iso n = 12, TBI-aCD3 n = 12). The MWM test was analyzed by two-factor, repeated-measure, two-way ANOVA (group × time) and others by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. c, MRI lesion volume 7 d post-TBI (TBI-iso n = 5, TBI-aCD3 n = 5), analyzed by two-sided, unpaired Student’s t-test. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. The red dashes indicate the lesion area. d, Lesion volume from H&E-stained brain sections 30 d post-TBI measured with ImageJ (TBI-iso n = 4, TBI-aCD3 n = 4), analyzed by two-sided, unpaired Student’s t-test. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. Scale bars, 1,000 µm. e, Immunofluorescence of neuronal death 7 d post-TBI at pericontusional cortex (DAPI, blue; TUNEL, red; 7-AAD, green). Scale bars, 200 µm (500 µm for zoomed out). TUNEL-positive cells were quantified using ImageJ (TBI-iso n = 5, TBI-aCD3 n = 5) and analyzed using two-sided, unpaired Student’s t-test. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. f, Immunofluorescence of Iba-1 at 30 d post-TBI in pericontusional cortex (DAPI, blue; Iba-1, red). Scale bars, 200 µm (500 µm for zoomed out). Iba-1+ cells quantified using ImageJ (sham-iso n = 4, TBI-iso n = 4, TBI-aCD3 n = 4), analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. g, Serum biomarkers 1 d post-TBI measured by Quanterix SiMoA and V-Plex proinflammatory assays (sham-iso n = 4, TBI-iso n = 12, TBI-aCD3 n = 12), analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Data are shown as box plots (min., max., interquartile range (IQR), median). d.p.i., d post-injury; NS, non-significant. All data represent biological replicates from two independent experiments.

a、治疗方案实验时间轴示意图(使用 BioRender.com 创建)。b、即时治疗组行为学测试(转棒试验、莫里斯水迷宫测试、探针测试、旷场焦虑样行为检测)(假手术组同型对照 n=8,TBI 组同型对照 n=12,TBI-aCD3 组 n=12)。莫里斯水迷宫采用双因素重复测量双因素方差分析(组别×时间),其余采用单因素方差分析结合 Tukey 多重比较。数据以均值±标准误表示。c、TBI 后 7 天 MRI 病灶体积(TBI 同型对照 n=5,TBI-aCD3 组 n=5),采用双侧非配对 t 检验分析。数据以均值±标准误表示。红色虚线标示病灶区域。d、TBI 后 30 天 H&E 染色脑切片病灶体积(使用 ImageJ 测量,TBI 同型对照 n=4,TBI-aCD3 组 n=4),采用双侧非配对 t 检验分析。数据以均值±标准误表示。比例尺:1,000 微米。e、TBI 后 7 天挫伤周边皮层神经元死亡免疫荧光检测(DAPI 蓝色,TUNEL 红色,7-AAD 绿色)。比例尺:200 微米(全景图 500 微米)。TUNEL 阳性细胞通过 ImageJ 定量(TBI 同型对照 n=5,TBI-aCD3 组 n=5)并采用双侧非配对 t 检验分析。 数据以均值±标准误表示。f 组:创伤性脑损伤后 30 天挫伤周围皮层 Iba-1 免疫荧光染色(DAPI 显蓝色,Iba-1 显红色)。比例尺:200 微米(缩略图 500 微米)。使用 ImageJ 软件定量 Iba-1 阳性细胞(假手术组同型对照 n=4,TBI 组同型对照 n=4,TBI-aCD3 组 n=4),采用单因素方差分析及 Tukey 多重比较法。数据以均值±标准误表示。g 组:采用 Quanterix SiMoA 和 V-Plex 促炎因子检测法测定创伤后 1 天血清生物标志物(假手术组同型对照 n=4,TBI 组同型对照 n=12,TBI-aCD3 组 n=12),采用单因素方差分析及 Tukey 多重比较法。数据以箱线图展示(最小值、最大值、四分位距、中位数)。d.p.i.:损伤后天数;NS:无统计学意义。所有数据均来自两次独立实验的生物学重复样本。

Extended Data Fig. 1. Nasal anti-CD3 improves behavioral outcomes at different treatment regimens and TBI severities.

扩展数据图 1. 鼻内抗 CD3 单抗通过不同治疗方案及 TBI 严重程度改善行为学结果

(a) Behavioral testing in the early treatment regimen for males of rotarod, Morris water maze, probe trial, and anxiety like behavior that is measured by the open field was assessed between (Sham-Iso n = 8, TBI-Iso n = 12, and TBI-aCD3 n = 12) groups in the early and (b) delayed treatment regimen for males and (c) immediate for females. Morris water maze analyzed by two-factor repeated measures two-way ANOVA (group x time); others by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Data shown as mean ± SEM. (d) Behavioral testing in the immediate treatment regimen for males in severe TBI (Depth: 1.5 mm, Diameter: 3.0 mm of the impact tip) of rotarod, Morris water maze, probe trial, and anxiety like behavior that is measured by the open field was assessed between (Sham-Iso n = 8, TBI-Iso n = 12, and TBI-aCD3 n = 12) groups in males and (e) females. Morris water maze analyzed by two-factor repeated measures two-way ANOVA (group x time); others by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Data shown as mean ± SEM. All data are biological replicates and are representative from two independent experiments. n.s. = non-significant.

(a) 早期治疗方案中雄性小鼠的行为学测试(转棒实验、Morris 水迷宫、探测试验及通过旷场实验测量的焦虑样行为)在(假手术组-Iso n=8、TBI-Iso n=12、TBI-aCD3 n=12)组间进行评估;(b) 延迟治疗方案中雄性小鼠及(c)雌性小鼠即刻治疗的行为学测试。Morris 水迷宫采用双因素重复测量双向方差分析(组别×时间),其余采用单因素方差分析结合 Tukey 多重比较。数据以均值±标准误表示。(d) 严重 TBI 雄性小鼠(撞击头深度 1.5mm/直径 3.0mm)即刻治疗方案中的转棒实验、Morris 水迷宫、探测试验及旷场焦虑样行为测试在(假手术组-Iso n=8、TBI-Iso n=12、TBI-aCD3 n=12)组间进行;(e) 雌性小鼠相应测试。Morris 水迷宫采用双因素重复测量双向方差分析(组别×时间),其余采用单因素方差分析结合 Tukey 多重比较。数据以均值±标准误表示。所有数据均为生物学重复样本,结果来自两次独立实验。n.s.表示无统计学显著性。

We then investigated the effect of delayed (14 d post-injury) nasal aCD3 treatment on behavioral outcomes in male mice and found no improvement in the treated the group compared with the TBI-iso control (Extended Data Fig. 1b). In addition to male mice, we investigated the effects of immediate nasal aCD3 treatment on TBI in female mice. We did not find notable differences in motor or spatial memory testing between the groups after moderate CCI. As reported in the literature, female rodents may outperform males in behavioral tasks after brain injury34–36. Thus, we were unable to demonstrate the beneficial effect of nasal aCD3 treatment in female mice at this injury level (Extended Data Fig. 1c).

随后,我们研究了延迟(伤后 14 天)鼻腔给予 aCD3 治疗对雄性小鼠行为学结果的影响,发现与 TBI-iso 对照组相比,治疗组未见改善(扩展数据图 1b )。除雄性小鼠外,我们还考察了即刻鼻腔 aCD3 治疗对雌性小鼠 TBI 的影响。在中度 CCI 后,我们未发现各组间在运动或空间记忆测试中存在显著差异。文献报道显示,脑损伤后雌性啮齿类动物在行为学任务中可能优于雄性 34–36 。因此,我们未能在此损伤程度下证明鼻腔 aCD3 治疗对雌性小鼠的获益效应(扩展数据图 1c )。

We then investigated the effect of nasal aCD3 treatment on behavioral outcomes in a more severe form of TBI (3 mm tip diameter and 1.5 mm depth) in both male and female mice. We found improvement in motor function and coordination in the TBI-aCD3 group when compared with TBI-iso control in both sexes (Extended Data Fig. 1d,e). There was partial restoration in spatial memory and increased time spent in the target quadrant during the probe trial in the nasal aCD3-treated mice compared with TBI-iso control in both sexes. Male mice treated with nasal aCD3 exhibited less anxiety-like behavior after severe TBI, but we were unable to assess the beneficial effects of nasal aCD3 in female mice because they did not develop an anxiety phenotype after severe TBI (Extended Data Fig. 1d,e). These data clearly demonstrate that nasal aCD3 improves behavioral outcomes in moderate and severe CCI-induced TBI, with a greater effect being observed in male mice.

随后,我们研究了鼻腔给予 aCD3 抗体治疗对雌雄两性小鼠更严重型 TBI(撞击头端直径 3 毫米、深度 1.5 毫米)行为学结局的影响。与 TBI-iso 对照组相比,两性 TBI-aCD3 治疗组均表现出运动功能和协调能力的改善(扩展数据图 1d,e )。鼻腔 aCD3 治疗组小鼠的空间记忆得到部分恢复,在探测试验中停留在目标象限的时间较 TBI-iso 对照组延长。在严重 TBI 后,鼻腔 aCD3 治疗的雄性小鼠表现出更少的焦虑样行为,但由于雌性小鼠在严重 TBI 后未出现焦虑表型,我们无法评估鼻腔 aCD3 对雌鼠的改善作用(扩展数据图 1d,e )。这些数据明确表明,鼻腔 aCD3 能改善中重度 CCI 诱导型 TBI 的行为学结局,且在雄性小鼠中观察到的疗效更为显著。

Nasal aCD3 mAb ameliorates TBI neuropathology

鼻腔给予 aCD3 单抗改善创伤性脑损伤神经病理学改变

TBI induces BBB disruption, edema, neuronal death and tissue loss, in addition to the increased production of inflammatory mediators and gliosis20. Therefore, we assessed the effects of nasal aCD3 on these neuropathological outcomes (Fig. 1a). We first measured the parenchymal lesion volume in sham-iso, TBI-aCD3 and TBI-iso groups at 7 d post-injury, using 3-tesla magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We found a reduction in lesion volume in the nasal aCD3-treated group compared with TBI-iso controls (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 2a). We also measured lesion volume at 1 month post-CCI using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and, consistent with the MRI, we found a reduction in lesion volume in TBI-aCD3 mice compared with the TBI-iso control (Fig. 1d). Nasal aCD3 also improved BBB integrity at 3 d post-injury compared with the TBI-iso control (Extended Data Fig. 2b). The percentage of brain edema in the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres at 3 d post-CCI was reduced in the ipsilateral hemisphere for the TBI-aCD3 group compared with the TBI-iso control (Extended Data Fig. 2c). CCI increased cell death, as measured by TUNEL staining at 7 d after brain injury (Fig. 1e), which was reduced in nasal aCD3 treatment compared with TBI-iso controls. Consistent with previous reports, we found that CCI was associated with an increase in microglia or macrophage activation (Iba-1 staining) at 30 d post-injury compared with sham-iso controls (Fig. 1f)20,37. We found that there was a reduction in microgliosis at 30 d post-injury in male mice in both the immediate and the early nasal aCD3 groups (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 2d). Of note, TBI has also been associated with changes in serum biomarkers38 and we found a reduction in several TBI serum biomarkers in the immediate nasal aCD3 group, including glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), UCH-L1 and the inflammatory cytokines IL-1b and CXCL1 versus controls. It is interesting that we also found an increase in the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the immediate nasal aCD3 group versus control animals (Fig. 1g). These markers could be used to assess the efficacy of treatment in humans. As in male mice, we found that nasal aCD3 reduced lesion volume (Extended Data Fig. 2e) and microgliosis at the lesion site in female mice after severe TBI (Extended Data Fig. 2f). These data clearly demonstrate that the behavioral improvements observed in TBI mice treated with nasal aCD3 are associated with enhanced tissue integrity, as indicated by neuropathology and serum biomarkers.

创伤性脑损伤(TBI)除引发炎症介质增加和神经胶质增生外,还会导致血脑屏障破坏、水肿、神经元死亡及组织缺损 20 。为此,我们评估了鼻腔给予 aCD3 抗体对这些神经病理学结局的影响(图 1a )。首先采用 3 特斯拉磁共振成像(MRI)检测假手术组、TBI-aCD3 治疗组和 TBI 对照组在损伤后 7 天的脑实质病灶体积,发现鼻腔 aCD3 治疗组的病灶体积较 TBI 对照组显著减小(图 1c 及扩展数据图 2a )。通过苏木精-伊红(H&E)染色检测损伤后 1 个月的病灶体积,结果与 MRI 一致:TBI-aCD3 组小鼠的病灶体积小于 TBI 对照组(图 1d )。与 TBI 对照组相比,鼻腔 aCD3 在损伤后 3 天还能改善血脑屏障完整性(扩展数据图 2b )。在损伤后 3 天,TBI-aCD3 组小鼠损伤同侧大脑半球的脑水肿比例较 TBI 对照组降低,而对侧半球无显著差异(扩展数据图 2c )。通过 TUNEL 染色检测发现,控制性皮质撞击伤(CCI)在脑损伤后 7 天会加剧细胞死亡(图 1e ),与 TBI-iso 对照组相比,鼻内 aCD3 治疗组该指标降低。与既往报道一致,我们发现 CCI 损伤后 30 天小胶质细胞/巨噬细胞活化标志物(Iba-1 染色)较假手术组升高(图 1f ) 20,37 。值得注意的是,在雄性小鼠中,无论是即刻还是早期鼻内 aCD3 治疗组,损伤后 30 天的小胶质细胞增生均有所减少(图 1f 及扩展数据图 2d )。需特别指出的是,TBI 还与血清生物标志物改变相关 38 ,我们在即刻鼻内 aCD3 治疗组观察到多个 TBI 血清标志物水平降低,包括胶质纤维酸性蛋白(GFAP)、UCH-L1 以及炎症细胞因子 IL-1β和 CXCL1。有趣的是,与对照组相比,即刻鼻内 aCD3 治疗组抗炎细胞因子 IL-10 水平升高(图 1g ),这些标志物或可用于评估人类治疗效果。与雄性小鼠结果类似,我们发现鼻内 aCD3 能减少雌性小鼠严重 TBI 后的病灶体积(扩展数据图 2e )及病灶区小胶质细胞增生(扩展数据图 2f )。 这些数据清楚地表明,经鼻腔 aCD3 治疗的创伤性脑损伤小鼠所表现出的行为改善与组织完整性增强相关,神经病理学检查和血清生物标志物检测均证实了这一点。

Extended Data Fig. 2. Nasal anti-CD3 ameliorates pathological outcomes at different treatment regimens and TBI severities.

扩展数据图 2. 鼻腔给予抗 CD3 单抗通过不同治疗方案改善不同程度创伤性脑损伤的病理学结局

(a) Unedited 3-Tesla serial images Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) taken 7 days post-TBI of (Fig. 1c). (b) Dextran 70-kDa (Green) for measurement of blood-brain barrier permeability between the groups (3days post-TBI). Scale bars are 1000 um. Data is shown as mean ± SEM, (Sham-Iso n = 3, TBI-Iso n = 4, and TBI-aCD3 n = 4) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. (c) Brain edema was analyzed on day 3 post-TBI and % water content was measured between the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. Data shown as mean ± SEM and n = 3-4 mice/group were used. Data was analyzed by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. (d) Immunofluorescence staining of Iba-1 30-days post-TBI for early treatment in males at the peri-contusional cortex for DAPI (blue) and Iba-1 (red). Scale bars are 250 um. Five sections of each sample were prepared and the area around the contusion was captured and the number of Iba-1 positive cells around the contusion were quantified by Image J. Data shown as mean ± SEM and n = 5 mice/group were used. Data was analyzed by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. (e) Brain sections were stained with DAPI (blue) at 30 days post severe TBI in females and lesion volume was measured by image J software. Data shown as mean ± SEM and n = 4 mice/group were used. Data was analyzed by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. Scale bars are 1000 um. (f) Immunofluorescence staining of Iba-1 30 days post severe TBI in females in the at the peri-contusional cortex for DAPI (blue) and Iba-1 (red). Scale bars are 250 um. Five sections of each sample were prepared and the area around the contusion was captured and the number of Iba-1 positive cells around the contusion were quantified by Image J. Data shown as mean ± SEM and n = 4 mice/group were used. Data was analyzed by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. All data are biological replicates and are representative from two independent experiments. n.s. = non-significant. DPI indicates Days Post Injury.

(a) 创伤性脑损伤(TBI)后 7 天获取的 3 特斯拉磁共振成像(MRI)连续图像(图 1c )。(b) 采用 70-kDa 右旋糖酐(绿色)测量各组间血脑屏障通透性(TBI 后 3 天)。比例尺为 1000 微米。数据以均值±标准误表示(假手术组-Iso n=3,TBI-Iso 组 n=4,TBI-aCD3 组 n=4),采用单因素方差分析及 Tukey 多重比较法进行统计分析。(c) TBI 后第 3 天分析脑水肿情况,并测量损伤侧与对侧大脑半球的水含量百分比。数据以均值±标准误表示,每组使用 3-4 只小鼠。采用双尾非配对 Student t 检验进行数据分析。(d) 雄性小鼠早期治疗组在 TBI 后 30 天进行 Iba-1 免疫荧光染色(损伤周边皮层),DAPI(蓝色)和 Iba-1(红色)标记。比例尺为 250 微米。每组制备 5 个切片,捕获挫伤周边区域并通过 Image J 软件定量挫伤周边 Iba-1 阳性细胞数量。数据以均值±标准误表示,每组使用 5 只小鼠。采用双尾非配对 Student t 检验进行数据分析。 (e) 雌性小鼠严重 TBI 后 30 天,脑切片经 DAPI 染色(蓝色显示),采用 Image J 软件测量病灶体积。数据以均值±标准误表示,每组 n=4 只小鼠。采用双侧非配对 Student t 检验进行数据分析。比例尺为 1000 微米。(f) 雌性小鼠严重 TBI 后 30 天,在挫伤周围皮层进行 Iba-1 免疫荧光染色,显示 DAPI(蓝色)和 Iba-1(红色)。比例尺为 250 微米。每个样本制备 5 张切片,捕获挫伤周围区域并使用 Image J 定量挫伤周围 Iba-1 阳性细胞数量。数据以均值±标准误表示,每组 n=4 只小鼠。采用双侧非配对 Student t 检验进行数据分析。所有数据均为生物学重复,结果来自两次独立实验。n.s.表示无统计学意义。DPI 指损伤后天数。

Nasal aCD3 mAb expands central and peripheral Treg cells after TBI

鼻腔给予抗 CD3 单克隆抗体(aCD3 mAb)在创伤性脑损伤(TBI)后促进中枢及外周调节性 T 细胞(Treg)扩增

TBI is associated with major changes in the cellular kinetics of both resident and infiltrating cells, which contribute to brain injury. Therefore, to characterize the effect of nasal aCD3 on TBI, we investigated the temporal roles of specific immune cell populations post-injury20. We performed flow cytometry analysis on immune cells isolated from cervical lymph nodes (cLNs), meninges and the ipsilateral hemisphere at multiple time points post-TBI. We found that the immediate treatment of nasal aCD3 increased the percentage of total CD4+ T cells and CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells in cLNs at 1 d (Extended Data Fig. 3a) and increased the total number of those in the meninges at 2 d post-injury (Fig. 2a,b). Nasal aCD3 also expanded the total number of CD4+ T cells in the brain at 3 and 7 d post-injury and increased CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells in the first 30 d post-injury compared with TBI isotype controls (Fig. 2a,b and Extended Data Figs. 3a and 4a). Of note, we did not observe an increase in CD4+ T cells expressing latency-associated peptide (LAP), a membrane-bound transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) compared with the TBI-iso group (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Figs. 3b and 4a). Thus, nasal aCD3 expands Treg cells to control neuroinflammation after TBI.

创伤性脑损伤(TBI)会导致驻留细胞和浸润细胞的细胞动力学发生重大变化,这些变化加剧了脑损伤。因此,为明确鼻腔给予 aCD3 抗体对 TBI 的作用机制,我们研究了损伤后特定免疫细胞亚群的时序性变化。通过流式细胞术分析 TBI 后多个时间点从颈淋巴结(cLNs)、脑膜及损伤同侧大脑半球分离的免疫细胞,发现鼻腔 aCD3 即时治疗可使损伤后 1 天 cLNs 中总 CD4+T 细胞及 CD4+FoxP3+T 细胞比例增加(扩展数据图),并在损伤后 2 天增加脑膜中这些细胞的总数(图)。与 TBI 同型对照组相比,鼻腔 aCD3 还使损伤后 3 天和 7 天脑内 CD4+T 细胞总数扩增,并在损伤后 30 天内持续增加 CD4+FoxP3+T 细胞数量(图及扩展数据图)。值得注意的是,与 TBI-iso 组相比,我们未观察到表达潜伏相关肽(LAP,一种膜结合型转化生长因子β)的 CD4+T 细胞增加(图。 2c 及扩展数据图 3b 和 4a )。因此,鼻腔给予 aCD3 可通过扩增 T reg 细胞来调控创伤性脑损伤后的神经炎症反应。

Extended Data Fig. 3. Nasal anti-CD3 ameliorates adaptive immune response following TBI.

扩展数据图 3. 鼻腔抗 CD3 治疗改善创伤性脑损伤后的适应性免疫应答。

(a) Flow cytometry analysis and quantification of CD4 + T cells, CD4+FoxP3 + and (b) CD8 + T cells, CD4 + LAP + , Th1, and Th17 at 1,3,7,14, and 30 days post TBI and nasal anti-CD3 treatment in the cervical lymph nodes, meninges, and Ipsilateral brain hemisphere. (Sham-Iso n = 4, TBI-Iso n = 6, TBI-aCD3 n = 6). Data shown as mean ± SEM and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons for every individual timepoint (c) Flow cytometry analysis and quantification of neutrophils, monocytes, classical monocytes (7 days post-TBI), and NK cells at 1,3,7,14, and 30 days post TBI and nasal anti-CD3 treatment in Ipsilateral brain hemisphere. (Sham-Iso n = 4, TBI-Iso n = 6, TBI-aCD3 n = 6). Data shown as mean ± SEM and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons for every individual timepoint. All data are biological replicates and are representative from two independent experiments.

(a) 流式细胞术分析及定量检测创伤性脑损伤(TBI)和鼻腔抗 CD3 单抗治疗后 1、3、7、14 和 30 天时颈淋巴结、脑膜及损伤侧大脑半球中 CD4+T 细胞、CD4+FoxP3+细胞、(b) CD8+T 细胞、CD4+LAP+细胞、Th1 和 Th17 细胞。(假手术组-Iso n=4,TBI-Iso 组 n=6,TBI-aCD3 组 n=6)。数据以均值±标准误表示,采用单因素方差分析及 Tukey 多重比较法对各时间点进行统计分析。(c) 流式细胞术分析及定量检测 TBI 和鼻腔抗 CD3 单抗治疗后 1、3、7、14 和 30 天时损伤侧大脑半球中性粒细胞、单核细胞、经典单核细胞(TBI 后 7 天)及 NK 细胞。(假手术组-Iso n=4,TBI-Iso 组 n=6,TBI-aCD3 组 n=6)。数据以均值±标准误表示,采用单因素方差分析及 Tukey 多重比较法对各时间点进行统计分析。所有数据均为生物学重复样本,结果代表两次独立实验。

Fig. 2. Nasal aCD3 expands FoxP3 Treg cells and modulates the adaptive immune response.

图 2. 鼻腔给予 aCD3 可扩增 FoxP3 T reg 细胞并调节适应性免疫应答。

a,b, Flow cytometry analysis and quantification of CD4+ (a) and CD4+FoxP3+ (b) Treg cells in the meninges and ipsilateral hemisphere at 1, 3, 7, 14 and 30 d (D) after TBI and treatment. c, Quantification of CD4+ subsets at the same time points. d, Analysis of CD11b+-infiltrated cells across these intervals. Groups included sham-iso (n = 4), TBI-iso (n = 6) and TBI-aCD3 (n = 6). Data are analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons for every individual timepoint. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. representing biological replicates from two independent experiments per timepoint for a–d. e, Immunofluorescence of meninges (2 d post-TBI) and brain (7 d post-TBI) samples from FoxP3-GFP mice with DAPI (blue), CD3 (pink), FoxP3 (green). Scale bars, 100 µm. IHC, immunohistochemistry. f, PCA plot of brain and blood Treg cells 7 d post-TBI. Brain and blood samples are pools of 5 mice and sham-iso brain samples are pools of 20 mice. Due to the low number of FoxP3⁺ cells recruited to the brain and ethical considerations, we limited the study to two biological replicates, following practices from previous studies in the field23. Despite this limitation, the consistent and robust results observed support the validity of our findings. g,h, Heatmaps of DEGs from blood (g) and brain (h) Treg cells at 7 d post-TBI using DESeq2 (FDR-corrected P < 0.05, n = 2 pooled samples per group). i, GSEA of GOBP 7 d post-TBI for brain Treg cells. The asterisks indicate enriched terms (q < 0.05). NES, normalized enrichment score. j, IPA analysis of DEGs from brain Treg cells in TBI-aCD3 versus TBI-iso using DESeq2 analysis (two-sided Wald’s test, FDR-corrected P < 0.05). One-sided Fisher’s exact test was used: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Results with FDR-corrected P < 0.05 were selected. k, Predicted upstream regulators using IPA for TBI-aCD3 versus TBI-iso. l, Quantification of FoxP3+IL-10+ Treg cells in the ipsilateral hemisphere 7 d post-TBI. Groups included sham-iso (n = 4), TBI-iso (n = 6) and TBI-aCD3 (n = 6). Data are shown as box plots (min., max., IQR, median), analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Data are from biological replicates and represent two independent experiments.

a,b,流式细胞术分析及定量检测创伤性脑损伤(TBI)后 1、3、7、14 和 30 天(D)脑膜与损伤同侧大脑半球中 CD4 + (a)和 CD4 + FoxP3 + (b)T reg 细胞。c,相同时间点 CD4 + 亚群的定量分析。d,各时间点 CD11b + 阳性浸润细胞分析。实验分组包括假手术同型对照组(n=4)、TBI 同型对照组(n=6)和 TBI-aCD3 治疗组(n=6)。数据采用单因素方差分析(ANOVA)结合 Tukey 多重比较法对各时间点进行统计学处理。a-d 数据以均值±标准误表示,每个时间点包含两项独立实验的生物学重复。e,FoxP3-GFP 小鼠脑膜(TBI 后 2 天)和脑组织(TBI 后 7 天)样本的免疫荧光染色:DAPI(蓝)、CD3(粉)、FoxP3(绿)。比例尺 100µm。IHC:免疫组织化学。f,TBI 后 7 天脑组织与血液 T reg 细胞的主成分分析(PCA)图。脑组织和血液样本为 5 只小鼠混合样本,假手术组脑样本为 20 只小鼠混合样本。鉴于脑内募集的 FoxP3⁺细胞数量较少及伦理考量,本研究遵循该领域既往研究规范,仅进行两项生物学重复实验 23 。 尽管存在这一局限性,我们观察到的持续且稳健的结果支持研究发现的可靠性。图 g、h 分别显示 TBI 后 7 天通过 DESeq2 分析获得的血液(g)和脑组织(h)T reg 细胞差异表达基因热图(FDR 校正 P 值<0.05,每组 n=2 混合样本)。图 i 为 TBI 后 7 天脑组织 T reg 细胞的 GOBP 基因集富集分析,星号标注显著富集条目(q 值<0.05)。NES 表示标准化富集分数。图 j 通过 IPA 分析比较 TBI-aCD3 组与 TBI-iso 组脑组织 T reg 细胞差异基因(采用 DESeq2 双尾 Wald 检验,FDR 校正 P 值<0.05),单尾 Fisher 精确检验标注: * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001,筛选 FDR 校正 P 值<0.05 的结果。图 k 展示 IPA 预测的 TBI-aCD3 组与 TBI-iso 组上游调控因子。图 l 定量分析 TBI 后 7 天损伤同侧半球 FoxP3 + IL-10 + T reg 细胞数量,实验分组包括假手术-iso 组(n=4)、TBI-iso 组(n=6)和 TBI-aCD3 组(n=6)。数据以箱线图呈现(最小值、最大值、四分位距、中位数),采用单因素方差分析结合 Tukey 多重比较检验。所有数据均来自生物学重复样本并代表两次独立实验。

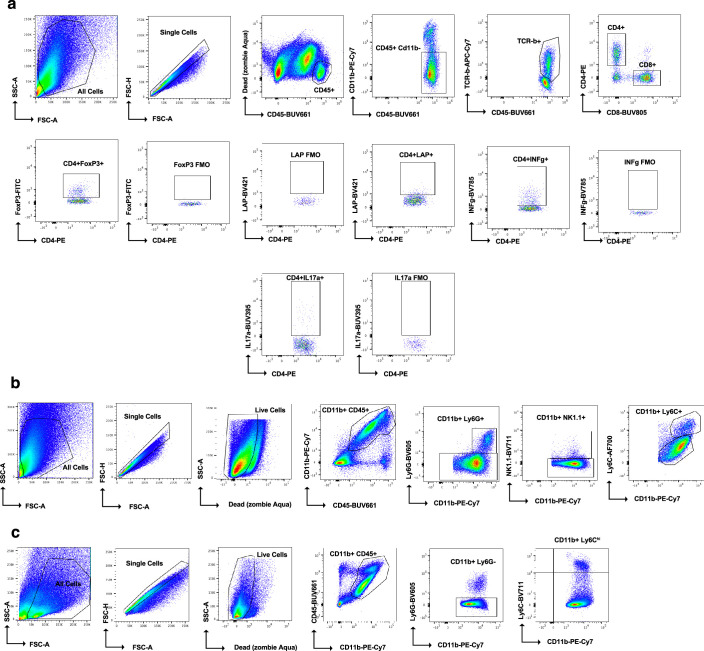

Extended Data Fig. 4. Gating strategy of different immune cells in TBI.

扩展数据图 4. TBI 中不同免疫细胞的门控策略。

(a) Gating strategy used to identify the different T-cell substypes. (b) Gating strategies used to identify different CD11b+ infiltrating cells and (c) CD11b+Ly6Chi monocytes.

(a) 用于识别不同 T 细胞亚群的设门策略。(b) 用于识别不同 CD11b+浸润细胞的设门策略及(c) CD11b+Ly6Chi 单核细胞的设门策略。

Nasal aCD3 mAb modulates the innate and adaptive immune response after TBI

鼻腔给予 aCD3 单抗可调节 TBI 后的先天性与适应性免疫应答

Nasal aCD3 also reduced the number of CD8+ cells at 14 and 30 d and helper T cells (TH1 and TH17 cells) at day 30 post-injury (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Figs. 3b and 4a). In addition, we found a significant reduction in neutrophil recruitment at day 1, monocytes at day 7 and natural killer cells at days 1 and 14 after CCI in the nasal aCD3 group compared with the TBI-iso controls (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Figs. 3c and 4b,c).

鼻腔给予 aCD3 还显著减少了伤后 14 天和 30 天的 CD8 + 细胞数量,以及伤后 30 天的辅助性 T 细胞(T H 1 和 T H 17 细胞)(图 2c 及扩展数据图 3b 和 4a )。此外,与 TBI 对照组相比,鼻腔 aCD3 治疗组在 CCI 后第 1 天中性粒细胞浸润、第 7 天单核细胞浸润以及第 1 天和第 14 天的自然杀伤细胞数量均出现显著减少(图 2d 及扩展数据图 3c 和 4b,c )。

Treg cells induced by nasal aCD3 have a unique immunomodulatory profile

鼻腔给予 aCD3 诱导产生的 T 细胞具有独特的免疫调节特性

As shown in Fig. 2b, nasal aCD3 increased CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells in the first 30 d post-injury compared with TBI isotype controls (Fig. 2b). To elucidate the mechanisms whereby aCD3-induced Treg cells may have contributed to post-TBI recovery, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis on CD4+FoxP3(GFP)+ Treg cells isolated from both the pericontusional brain tissue and blood of the sham and injured mice 7 d after CCI (Fig. 2f–k, Extended Data Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table 1). Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that the transcriptomic profile of brain FoxP3 Treg cells was markedly different from blood FoxP3 Treg cells after TBI (Fig. 2f). Consistent with recent reports23, we found increased expression of multiple immunomodulatory and trophic factor genes (Il10, Spp1, Gas6, Igf1, Dab2, Lif, Areg, Il1r2, Irf8, Osm, Tgfa, Ccl8, and Hmox1) in brain-infiltrating Treg cells from TBI mice compared with blood Treg cells from sham mice (Extended Data Fig. 5b).

如图 2b 所示,与 TBI 同型对照组相比,鼻腔给予 aCD3 在损伤后 30 天内增加了 CD4 + FoxP3 + T reg 细胞数量(图 2b )。为阐明 aCD3 诱导的 T reg 细胞促进 TBI 后恢复的机制,我们在 CCI 术后 7 天对假手术组和损伤组小鼠挫伤周边脑组织及血液中分离的 CD4 + FoxP3(GFP) + T reg 细胞进行了 RNA 测序分析(图 2f–k 、扩展数据图 5a 及补充表 1 )。主成分分析(PCA)显示,TBI 后脑部 FoxP3 T reg 细胞的转录组特征与血液 FoxP3 T reg 细胞存在显著差异(图 2f )。与近期研究报道一致 23 ,我们发现相较于假手术组小鼠血液 T reg 细胞,TBI 小鼠脑浸润 T reg 细胞中多种免疫调节及神经营养因子基因(Il10、Spp1、Gas6、Igf1、Dab2、Lif、Areg、Il1r2、Irf8、Osm、Tgfa、Ccl8 和 Hmox1)表达上调(扩展数据图 5b )。

Extended Data Fig. 5. Nasal anti-CD3 induces a unique immune modulatory signature in FoxP3 Tregs.

扩展数据图 5. 鼻腔给予抗 CD3 单抗可诱导 FoxP3 调节性 T 细胞产生独特的免疫调节特征

(a) Gating strategy used to identify and sort CD4+FoxP3(GFP)+ from the ipsilateral hemisphere of the brain and blood. (b) Overlap in differentially expressed genes in injured brain vs. sham blood Treg cells after injury with another study investigating the transcriptomic effects of stroke in brain vs. blood Treg cells23. (c) Selected top predicted regulators using IPA based on DEGs in TBI-aCD3 vs. TBI-Iso blood Treg cells at 7 days post-TBI identified using DESeq2 analysis (two-sided Wald test, FDR-corrected P < 0.05). One-sided Fisher’s exact test. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Results with FDR-corrected P < 0.05 were selected. (d) Predicted upstream regulator using IPA analysis based on DEGs of brain Tregs in TBI-aCD3 vs. TBI-Iso identified using DESeq2 analysis (two-sided Wald test, FDR-corrected P < 0.05). Due to the low number of FoxP3⁺ cells recruited to the brain, and ethical considerations, we limited the study to two biological replicates, following practices from previous studies in the field23. Despite this limitation, the consistent and robust results observed support the validity of our findings.

(a) 用于鉴定和分选脑损伤同侧半球及血液中 CD4 + FoxP3(GFP) + 细胞的设门策略。(b) 本研究中脑损伤组与假手术组血液 Treg 细胞的差异表达基因与另一项研究脑卒中后脑部 vs 血液 Treg 细胞转录组效应的重叠分析 23 。(c) 基于 DESeq2 分析(双侧 Wald 检验,FDR 校正 P<0.05)筛选的 TBI-aCD3 组与 TBI-Iso 组血液 Treg 细胞在损伤后 7 天的差异表达基因,通过 IPA 分析预测的顶级调控因子。单侧 Fisher 精确检验。*P<0.05,**P<0.01,***P<0.001。选择 FDR 校正 P<0.05 的结果。(d) 基于 DESeq2 分析(双侧 Wald 检验,FDR 校正 P<0.05)鉴定的 TBI-aCD3 组与 TBI-Iso 组脑部 Treg 细胞差异表达基因,通过 IPA 分析预测的上游调控因子。由于募集至脑部的 FoxP3⁺细胞数量较少及伦理考量,本研究遵循该领域既往研究惯例 23 仅采用两个生物学重复。尽管存在此局限,观察到的稳定可靠结果仍支持本研究发现的有效性。

We first examined the effects of TBI and nasal aCD3 treatment on blood FoxP3 Treg cells (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Table 1). We found that FoxP3 Treg cells isolated from nasally treated aCD3 TBI mice had a unique transcriptomic signature with upregulation of several genes involved in Treg cell proliferation and homeostasis (Cd47 (ref. 39), Ndfip1 (ref. 40), Cd2 (ref. 41)) and Treg cell function (Lef1 (ref. 42), Lgals1 (ref. 43) and Runx1 (ref. 44)). Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) revealed IL-10 as a top activated upstream regulator in blood aCD3-induced FoxP3 Treg cells compared with TBI-iso FoxP3 Treg cells along with other transcription factors relevant for Treg cell development and function (Foxo3 and Foxo4)45 (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Notably, both Foxo4 and Stat3 have been reported to regulate IL-10 transcription in CD4+ Treg cells46.

我们首先检测了创伤性脑损伤(TBI)和鼻腔 aCD3 治疗对血液 FoxP3 T 细胞的影响(图 1,补充表 2)。研究发现,从鼻腔给予 aCD3 治疗的 TBI 小鼠中分离的 FoxP3 T 细胞具有独特的转录组特征,表现为多个参与 T 细胞增殖与稳态(Cd47(参考文献 5)、Ndfip1(参考文献 6)、Cd2(参考文献 7))以及 T 细胞功能(Lef1(参考文献 9)、Lgals1(参考文献 10)和 Runx1(参考文献 11))的基因表达上调。Ingenuity 通路分析(IPA)显示,与 TBI-iso FoxP3 T 细胞相比,血液 aCD3 诱导的 FoxP3 T 细胞中 IL-10 是最活跃的上游调节因子,同时还包括其他与 T 细胞发育和功能相关的转录因子(Foxo3 和 Foxo4)(扩展数据图 16)。值得注意的是,已有报道表明 Foxo4 和 Stat3 均可调控 CD4 T 细胞中 IL-10 的转录。

We then examined the effects of TBI and nasal aCD3 treatment on brain-infiltrating Treg cells (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Table 1). We found both TBI groups (treated and untreated) had upregulated genes enriched in immune regulation (Spp1, Lgals3, Arg1, Ccl3, Ccl8, Hmox1, Ctsl, Lgals1, and Il1rn) (Fig. 2h). In addition, nasal aCD3-induced Treg cells had further increased expression of genes involved in immunomodulation (Lrp1, Tyrobp, Cxcl10, and Itgam), regulation of phagocytosis (Rab31 and Rab7), neurotrophic factors (Igf1 and Psap), lipid homeostasis (Abca1 and Lpl) and other genes required for Treg cell immunosuppressive function (Dab2 (ref. 47), Plau48 and Lgmn49). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and IPA revealed enrichment of biological pathways involved in migration, regulation of immune response, phagocytosis, neurogenesis, homeostasis and secretory functions in brain TBI-aCD3-FoxP3 Treg cells compared with brain sham-iso controls (Fig. 2i) and TBI-iso-FoxP3 Treg cells (Fig. 2j). Similar to blood FoxP3+ Treg cells, IPA identified IL-10 and Stat3 among the most activated upstream regulators of Treg cells in the brain of TBI mice treated with nasal aCD3 (Fig. 2k and Extended Data Fig. 5d). The IL-10–Stat3 axis has been reported as playing a role in the immune tolerance conferred by Treg cells50; consistent with this, flow cytometry analysis of brain Treg cells showed upregulation of IL-10 expression in aCD3-treated animals compared with TBI-iso controls (Fig. 2l). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that peripheral and central Treg cells possess unique immunomodulatory profiles associated with the amelioration of TBI via nasal aCD3 treatment.

随后我们检测了 TBI 和鼻腔 aCD3 治疗对脑浸润 T reg 细胞的影响(图 2h 和附表 1 )。发现两个 TBI 组(治疗组与未治疗组)均出现免疫调节相关基因(Spp1、Lgals3、Arg1、Ccl3、Ccl8、Hmox1、Ctsl、Lgals1 和 Il1rn)上调(图 2h )。此外,鼻腔 aCD3 诱导的 T reg 细胞还进一步增加了以下基因表达:免疫调节相关基因(Lrp1、Tyrobp、Cxcl10 和 Itgam)、吞噬作用调控基因(Rab31 和 Rab7)、神经营养因子(Igf1 和 Psap)、脂质稳态基因(Abca1 和 Lpl)以及 T reg 细胞免疫抑制功能所需的其他基因(Dab2(参考文献 47 )、Plau 48 和 Lgmn 49 )。基因集富集分析(GSEA)和 IPA 显示,与假手术对照组(图 2i )及 TBI-iso-FoxP3 T reg 细胞组(图 2j )相比,TBI-aCD3-FoxP3 T reg 细胞中涉及迁移、免疫应答调控、吞噬作用、神经发生、稳态和分泌功能的生物通路显著富集。 与血液中的 FoxP3 + T reg 细胞类似,IPA 分析发现 IL-10 和 Stat3 是鼻腔 aCD3 治疗的 TBI 小鼠脑内 T reg 细胞最活跃的上游调节因子(图 2k 及扩展数据图 5d )。已有报道表明 IL-10-Stat3 轴在 T reg 细胞介导的免疫耐受中发挥作用 50 ;与此一致,脑部 T reg 细胞的流式细胞分析显示,与 TBI-iso 对照组相比,aCD3 治疗组动物的 IL-10 表达上调(图 2l )。综上所述,这些发现表明外周和中枢 T reg 细胞具有独特的免疫调节特征,这些特征与鼻腔 aCD3 治疗改善 TBI 相关。

Nasal aCD3 mAb modulates the microglial inflammation after TBI

鼻腔给予 aCD3 单抗调控 TBI 后小胶质细胞炎症反应

Microglia play a critical role in TBI pathogenesis and their adherent activation contributes to long-term functional deficits after TBI20. Nasal aCD3 treatment increased the migration of FoxP3+ Treg cells to the meninges and CCI lesion site (Fig. 2e), where they were found to be in close contact with microglial dendrites after injury (Fig. 3a). Thus, to further elucidate the effects of TBI and immediate nasal aCD3 treatment on the microglial inflammatory profile post-injury, we performed RNA-seq analysis on sorted microglial single-cell suspensions from the ipsilateral hemisphere of the mouse brains, using the microglia-specific 4D4+ antibody51 (Extended Data Fig. 6a) at 7 and 30 d post-CCI (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 2). In analyzing the highest expressed genes in the sham-iso, TBI-iso and TBI-aCD3 microglial groups, we found that multiple microglial genes, including Cx3cr1,

Hexb and Tmem119, were among the highest expressed (Extended Data Fig. 6b). A heatmap of the microglial gene signature demonstrated that the TBI-iso and TBI-aCD3 groups had overall similar transcriptomic profiles at 7 d, yet with demonstration of early upregulation of anti-inflammatory genes such as Cx3cr1, CD33, Hspa1a, and Hspa1b, whereas there was a clear modulation of the microglial transcriptomic signature in TBI-aCD3 group toward the sham-iso phenotype at 30 d post-injury (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 2), including the downregulation of microglial proinflammatory genes (Il6, Il18, Cd36, Ifitm3, and Lgals1) and upregulation of key homeostatic genes (Tgfbr2, Adgrg1, Mertk, Rhob, Atp8a2, Abcc3, Fscn1, Pde3b, Inpp4b, and Cmklr1).

小胶质细胞在 TBI 发病机制中起关键作用,其持续性激活会导致 TBI 后长期功能缺损 20 。鼻腔 aCD3 治疗增加了 FoxP3 + T reg 细胞向脑膜和 CCI 损伤部位的迁移(图 2e ),这些细胞被发现与损伤后的小胶质细胞树突密切接触(图 3a )。为进一步阐明 TBI 及鼻腔 aCD3 即刻治疗对损伤后小胶质细胞炎症表型的影响,我们使用小胶质细胞特异性抗体 4D4 + 51 (扩展数据图 6a ),对 CCI 后 7 天和 30 天小鼠大脑同侧半球分选的小胶质细胞单细胞悬液进行 RNA-seq 分析(图 3b 及补充表 2 )。在分析假手术组、TBI 对照组和 TBI-aCD3 治疗组小胶质细胞中高表达基因时,发现包括 Cx3cr1、Hexb 和 Tmem119 在内的多个小胶质细胞基因表达量最高(扩展数据图 6b )。 小胶质细胞基因特征的热图分析显示,TBI-iso 组和 TBI-aCD3 组在损伤后 7 天具有总体相似的转录组特征,但已表现出抗炎基因(如 Cx3cr1、CD33、Hspa1a 和 Hspa1b)的早期上调。而到损伤后 30 天时,TBI-aCD3 组的小胶质细胞转录组特征明显向假手术组表型转变(图 3c 和补充表 2 ),表现为小胶质细胞促炎基因(Il6、Il18、Cd36、Ifitm3 和 Lgals1)的下调,以及关键稳态基因(Tgfbr2、Adgrg1、Mertk、Rhob、Atp8a2、Abcc3、Fscn1、Pde3b、Inpp4b 和 Cmklr1)的上调。

Fig. 3. Nasal aCD3 modulates the microglial inflammatory response after TBI.

图 3. 鼻腔给予 aCD3 调节 TBI 后小胶质细胞的炎症反应

a, Immunofluorescence of ipsilateral brain lesion (7 d post-TBI) from FoxP3-GFP mice for DAPI (blue), CD3 (pink), FoxP3 (green) and Iba-1 (red) showing FoxP3 Treg cells in close proximity to Iba-1. Scale bars, 100 μm and 50 μm for the enlarged image. b, Experimental timeline schematic for microglial bulk RNA-seq at 7 and 30 d after TBI and treatment (created with BioRender.com). c, Heatmap of DEGs from microglia at 7 and 30 d post-TBI identified using DESeq2 analysis (two-sided LRT, n = 4 mice per group, FDR-corrected P < 0.05). d, Microglial core sensome genes at 7 and 30 d in TBI-aCD3 versus TBI-iso. Genes are colored by their function53,107,108. Emboldened DEGs have an asterisk: FDR-corrected P < 0.05; *P < 0.05 (DESeq2 analysis, two-sided Wald’s test, n = 4 mice per group). e, GSEA of GOBP at 7 and 30 d post-TBI based on the following pairwise comparisons: TBI-iso versus sham-iso and TBI-aCD3 versus sham-iso; the asterisk indicates enriched terms (q-value < 0.05). NES, normalized enrichment score. f, Heatmap of genes involved in inflammatory response from microglia at 30 d post-TBI. Genes identified with an FDR-corrected P < 0.05 using DESeq2 analysis are indicated by an asterisk (two-sided LRT, n = 4 mice per group). Genes were identified from the GOBP term inflammatory response as well as microglial inflammatory genes89. g, Heatmap of DAM and MGnD genes at 30 d post-TBI. Genes identified with an FDR-corrected P < 0.05 using DESeq2 analysis are indicated by an asterisk (two-sided LRT, n = 4 mice per group). Genes were identified based on the previous work of our group and others51,61. h, RT–qPCR of microglia sorted from the ipsilateral hemisphere at 7 and 30 d post-TBI. Expression was normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and presented relative to that of sham-iso animals (sham-iso n = 4, TBI-iso n = 5, TBI-aCD3 n = 5), analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. All data are biological replicates and represent two independent experiments.

a,FoxP3-GFP 小鼠创伤性脑损伤后 7 天同侧脑损伤区域的免疫荧光染色:DAPI(蓝色)、CD3(粉红色)、FoxP3(绿色)和 Iba-1(红色)显示 FoxP3 T 细胞与 Iba-1 紧密相邻。比例尺:主图 100 微米,放大图 50 微米。b,创伤性脑损伤后 7 天和 30 天小胶质细胞批量 RNA 测序及治疗实验时间轴示意图(使用 BioRender.com 制作)。c,采用 DESeq2 分析鉴定的创伤性脑损伤后 7 天和 30 天小胶质细胞差异表达基因热图(双侧似然比检验,每组 n=4 只小鼠,FDR 校正 P<0.05)。d,TBI-aCD3 组与 TBI-iso 组在 7 天和 30 天时小胶质细胞核心感应组基因表达。基因按功能 53,107,108 着色。加粗的差异表达基因标有星号:FDR 校正 P<0.05; * P<0.05(DESeq2 分析,双侧 Wald 检验,每组 n=4 只小鼠)。e,基于以下组间比较的创伤性脑损伤后 7 天和 30 天 GOBP 基因集富集分析:TBI-iso 组对比假手术-iso 组、TBI-aCD3 组对比假手术-iso 组;星号标注富集条目(q 值<0.05)。NES,标准化富集分数。f,创伤性脑损伤后 30 天小胶质细胞炎症反应相关基因热图。 经 DESeq2 分析(双侧 LRT,每组 n=4 只小鼠)以 FDR 校正 P 值<0.05 筛选的基因用星号标注。这些基因来源于 GOBP 术语"炎症反应"条目及小胶质细胞炎症相关基因 89 。图 g 显示创伤性脑损伤(TBI)后 30 天的 DAM 与 MGnD 基因热图。经 DESeq2 分析(双侧 LRT,每组 n=4 只小鼠)以 FDR 校正 P 值<0.05 筛选的基因用星号标注,基因筛选基于本课题组及他人既往研究 51,61 。图 h 为 TBI 后 7 天和 30 天同侧半球分选小胶质细胞的 RT-qPCR 结果,表达量以甘油醛-3-磷酸脱氢酶(GAPDH)为内参,数据相对于假手术对照组(假手术组 n=4,TBI 对照组 n=5,TBI-aCD3 组 n=5)呈现,采用单因素方差分析结合 Tukey 多重比较。数据以均值±标准误表示,所有数据均为生物学重复,代表两次独立实验。

Extended Data Fig. 6. Nasal anti-CD3 modulates chronic microglial response after TBI for different treatment regimens and TBI severities.

扩展数据图 6. 鼻腔给予抗 CD3 单抗通过不同治疗方案调节 TBI 后小胶质细胞慢性反应(适用于不同创伤严重程度)

(a) Gating strategy for microglia. (b) Relative expression of cell types in Sham-Iso microglia (n = 3). (c) RT- qPCR of ipsilateral hemisphere 7 and 30 days post-TBI (immediate treatment males). Expression was normalized to GAPDH and presented relative to Sham-Iso. Data shown as mean ± SEM, (Sham-Iso n = 6, TBI-Iso n = 8, TBI-aCD3 n = 8) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. (d) Heatmap signature of DEGs 30 days post-TBI (early treatment males) identified using DESeq2 analysis (two-sided likelihood ratio test, n = 5 mice/group, FDR-corrected P < 0.05). (e) Heatmap of genes in inflammatory response and genes of disease-associated microglia (DAM) and neurodegenerative microglia (MGnD) 30 days post-TBI (early treatment males). Genes identified with an FDR-corrected p-value < 0.05 using DESeq2 analysis are bolded (two-sided likelihood ratio test, n = 5 mice/group). (f) GSEA analysis of GO Biological Processes (BP) comparing TBI-aCD3 vs. TBI-Iso groups 30 days post-TBI (early treatment male mice). NES, normalized enrichment score. (g) RT- qPCR of ipsilateral hemisphere 30 days post-TBI (early treatment males). Expression normalized to GAPDH and presented relative to Sham-Iso. Data shown as mean ± SEM, (Sham-Iso n = 5, TBI-Iso n = 6, TBI-aCD3 n = 6) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. (h) Venn diagram of DEGs in comparisons with Sham-Iso microglia group as baseline 30 days post-severe TBI (immediate treatment female mice): TBI-Iso, and TBI-aCD3. (i) Heatmap genes involved in inflammatory response and (DAM) and (MGnD) at 30 days following severe TBI (immediate treatment females). Genes identified with FDR-corrected p-value < 0.05 using DESeq2 analysis are bolded (two-sided likelihood ratio test, n = 5 mice/group). (j) RT- qPCR of ipsilateral hemisphere 30 days post-severe TBI (immediate treatment female). Expression was normalized to GAPDH and presented relative to Sham-Iso. Data shown as mean ± SEM, (Sham-Iso n = 5, TBI-Iso n = 6, TBI-aCD3 n = 6) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. All data are biological replicates and are representative from two independent experiments. n.s. = non-significant.

(a) 小胶质细胞的分选策略。(b) Sham-Iso 组小胶质细胞中各细胞类型的相对表达量(n = 3)。(c) TBI 后 7 天和 30 天损伤同侧大脑半球的 RT-qPCR 结果(即刻治疗雄性组)。表达量以 GAPDH 为内参,相对于 Sham-Iso 组标准化。数据显示为均值±SEM(Sham-Iso n = 6,TBI-Iso n = 8,TBI-aCD3 n = 8),采用单因素方差分析及 Tukey 多重比较检验。(d) TBI 后 30 天差异表达基因(DEGs)的热图特征(早期治疗雄性组),通过 DESeq2 分析鉴定(双侧似然比检验,n = 5 只/组,FDR 校正 P < 0.05)。(e) TBI 后 30 天炎症反应相关基因及疾病相关小胶质细胞(DAM)与神经退行性小胶质细胞(MGnD)基因热图(早期治疗雄性组)。通过 DESeq2 分析鉴定 FDR 校正 p 值<0.05 的基因以加粗显示(双侧似然比检验,n = 5 只/组)。(f) TBI 后 30 天 TBI-aCD3 组与 TBI-Iso 组的 GO 生物过程(BP)GSEA 分析(早期治疗雄性小鼠组)。NES,标准化富集分数。(g) TBI 后 30 天损伤同侧大脑半球的 RT-qPCR 结果(早期治疗雄性组)。 以 GAPDH 为内参进行标准化表达,数据表示为相对于 Sham-Iso 组的相对值(Sham-Iso 组 n=5,TBI-Iso 组 n=6,TBI-aCD3 组 n=6),采用单因素方差分析及 Tukey 多重比较。(h)以 Sham-Iso 小胶质细胞组为基线(严重 TBI 后 30 天,雌性小鼠即刻治疗组),通过维恩图展示 TBI-Iso 组与 TBI-aCD3 组的差异表达基因。(i)热图显示严重 TBI 后 30 天(雌性即刻治疗组)炎症反应相关基因及(DAM)与(MGnD)相关基因。经 DESeq2 分析(双侧似然比检验,每组 n=5),FDR 校正 p 值<0.05 的基因以加粗标示。(j)严重 TBI 后 30 天(雌性即刻治疗组)损伤同侧半球的 RT-qPCR 结果。以 GAPDH 为内参进行标准化表达,数据表示为相对于 Sham-Iso 组的相对值(Sham-Iso 组 n=5,TBI-Iso 组 n=6,TBI-aCD3 组 n=6),采用单因素方差分析及 Tukey 多重比较。所有数据均为生物学重复,结果来自两次独立实验。n.s.表示无统计学意义。

Microglia possess a unique transcriptomic signature that enables them to perform sensing, homeostatic and housekeeping functions, which vary according to the brain’s physiological or pathological state52. To determine the effects of TBI and nasal anti-CD3 on these essential microglial functions, we examined the microglial sensome dataset for genes and pathways involved in each of these functions53. At 7 d post-TBI, we found that microglia from the nasal aCD3-treated group, compared with TBI-iso, were associated with increased expression of homeostatic and sensing genes involved in pattern recognition receptors (Tlr1), Fc receptors (Cmtm7), Siglec receptors (Cd33), cell–cell interaction (Cd84 and Lag3) and chemokine receptors (Cx3cr1) (Fig. 3d). Cd33 and Lag3 were among the most significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the TBI aCD3-treated group compared with TBI-iso control at 7 d post-injury. CD33 activity has been implicated in processes including microglial endogenous ligand receptors and sensors, adhesion processing of immune cells and inhibition of cytokines release by monocytes54,55. Lymphocyte activation gene-3 (Lag3) regulates T cell expansion and limits the duration and intensity of the immune response56. Moreover, the TBI aCD3-treated group exhibited downregulation of Cd14, a key regulator of microglial proinflammatory responses to injury57. At 30 d post-injury, we found that nasal aCD3 treatment was associated with increased expression of several transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-signaling genes, including Smad3, Tgfbr1 and Tgfbr2 compared with TBI-iso control (Fig. 3c,d and Supplementary Table 2)58. TGF-β is required for maintaining the microglial homeostatic state59 and modulating microglia-mediated inflammation after acute brain injury60. Nasal aCD3 treatment was also associated with decreased expression of sensing genes involved in cytokine receptor (Tnfrsf17), FC receptor (Fcgr1, Fcgr4, Fcgr3, and Fcer1g) and pattern recognition receptors (Cd74, Tlr6, Upk1b, and Selplg) compared with TBI-iso control (Fig. 3d).

小胶质细胞具有独特的转录组特征,使其能够执行感知、稳态维持和管家功能,这些功能会随大脑生理或病理状态的变化而改变 52 。为探究创伤性脑损伤(TBI)和鼻腔抗 CD3 单抗对这些关键小胶质细胞功能的影响,我们检测了参与各项功能的微胶质感知组基因及通路 53 。在 TBI 后第 7 天,与 TBI-iso 组相比,鼻腔 aCD3 治疗组的小胶质细胞显示出参与模式识别受体(Tlr1)、Fc 受体(Cmtm7)、Siglec 受体(Cd33)、细胞间相互作用(Cd84 和 Lag3)以及趋化因子受体(Cx3cr1)的稳态与感知基因表达上调(图 3d )。其中 Cd33 和 Lag3 是 TBI 后 7 天 aCD3 治疗组相较于 TBI-iso 对照组差异最显著的基因(DEGs)。CD33 活性已被证实参与微胶质细胞内源性配体受体与传感器的调控、免疫细胞粘附处理以及单核细胞细胞因子释放抑制等过程 54,55 。 淋巴细胞激活基因-3(Lag3)可调节 T 细胞增殖并限制免疫反应的持续时间和强度 56 。此外,创伤性脑损伤 aCD3 治疗组表现出 Cd14(小胶质细胞对损伤促炎反应的关键调节因子)的下调 57 。在损伤后 30 天,我们发现与 TBI-iso 对照组相比,鼻腔 aCD3 治疗与多个转化生长因子β(TGF-β)信号通路基因(包括 Smad3、Tgfbr1 和 Tgfbr2)表达增加相关(图 3c,d 和补充表 2 ) 58 。TGF-β是维持小胶质细胞稳态 59 以及调节急性脑损伤后小胶质细胞介导的炎症反应所必需的 60 。与 TBI-iso 对照组相比,鼻腔 aCD3 治疗还导致细胞因子受体(Tnfrsf17)、FC 受体(Fcgr1、Fcgr4、Fcgr3 和 Fcer1g)及模式识别受体(Cd74、Tlr6、Upk1b 和 Selplg)相关感知基因表达降低(图 3d )。

We then performed GSEA comparing the TBI groups with sham-iso controls at 7 and 30 d post-injury. At 7 d post-injury, we observed an upregulation in pathways involved in oxidative stress and neuron apoptosis in the TBI-iso group compared with the sham-iso group. The TBI-aCD3-treated animals had less upregulation of genes in these pathways and more upregulation in microglial pathways involved in the regulation of anti-inflammatory IL-10 production, phagocytosis and tolerance induction at 7 d post-injury (Fig. 3e). At 30 d post-TBI, we found enrichment of pathways involved in proinflammatory mechanisms (IL-6, IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor production), adaptive immune response, T cell cytotoxicity and cell killing pathways in the TBI-iso control compared with the sham-iso group. However, TBI-aCD3-treated animals had less upregulation of genes in these proinflammatory pathways and more upregulation in biological pathways involved in regulation of phagocytosis and cytokine production (Fig. 3e).

随后我们通过 GSEA 分析比较了创伤性脑损伤组与假手术对照组在伤后 7 天和 30 天的基因表达差异。伤后 7 天时,与假手术组相比,TBI-iso 组显示出氧化应激和神经元凋亡相关通路上调。而经 TBI-aCD3 治疗的动物在这些通路中的基因上调程度较轻,同时在调控抗炎因子 IL-10 生成、小胶质细胞吞噬功能及免疫耐受诱导等通路上调更为显著(图 3e )。至创伤后 30 天,与假手术组相比,TBI-iso 对照组中促炎机制(IL-6、IL-1 及肿瘤坏死因子生成)、适应性免疫应答、T 细胞毒性及细胞杀伤相关通路呈现富集。但 TBI-aCD3 治疗组动物在这些促炎通路中的基因上调减弱,而在调控吞噬作用与细胞因子生成的生物学通路上调更为明显(图 3e )。

Previous studies have suggested an association between microglia-mediated chronic inflammation after TBI and subsequent chronic neurodegeneration20,52. To investigate this relationship, we analyzed the expression levels of inflammatory response genes and genes characteristic of disease-associated microglia (DAMs)61 and neurodegenerative microglia (MGnDs)51 in all three groups at 30 d post-injury. We found that the TBI-iso microglia had a unique proinflammatory response (Fig. 3f) and a DAM or MGnD signature (Fig. 3g), because we found increased expression of key proinflammatory (Casp1, Nfkbia, C5ar1, Lyz1, Ifitm3, Il6, Lyz2, Cd86, and Irgm1), DAM-1 and -2 genes (B2m, Cstb, Cd52, Cd9, Cst7, Fth1, Ccl6, and Tyrobp) and MGnD microglial genes (Cybb, Gpnmb, Lgals3, and Clec7a)51,61. Importantly, several of these genes were downregulated in nasal aCD3-treated mice, approaching expression levels observed in the sham group (Fig. 3f-g).

先前研究表明,创伤性脑损伤(TBI)后小胶质细胞介导的慢性炎症与后续慢性神经退行性病变存在关联 20,52 。为探究这一关系,我们在损伤后 30 天检测了三组实验对象的炎症反应基因表达水平,以及疾病相关小胶质细胞(DAMs) 61 和神经退行性小胶质细胞(MGnDs) 51 的特征基因。研究发现 TBI-iso 组小胶质细胞呈现独特的促炎反应(图 3f )及 DAM/MGnD 特征(图 3g ),表现为关键促炎基因(Casp1、Nfkbia、C5ar1、Lyz1、Ifitm3、Il6、Lyz2、Cd86 和 Irgm1)、DAM-1/-2 基因(B2m、Cstb、Cd52、Cd9、Cst7、Fth1、Ccl6 和 Tyrobp)及 MGnD 小胶质细胞基因(Cybb、Gpnmb、Lgals3 和 Clec7a)表达上调 51,61 。值得注意的是,经鼻腔 aCD3 单抗治疗的小鼠中,多个基因表达下调至接近假手术组水平(图 3f-g )。

Consistent with the microglial transcriptomic data, quantitative PCR with reverse transcription (RT–qPCR) from ipsilateral hemisphere sorted microglia (Fig. 3h) and brain tissue (Extended Data Fig. 6c) revealed that, compared with the TBI-iso control, nasal aCD3 treatment increased the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine Il10 in both microglia and brain tissue at 7 d post-injury. Moreover, treatment reduced several proinflammatory markers in microglia (Clec7a, Tlr2, Il1b, Tnf, Cd86, and Il18) and brain tissue (Il6, Tnf, Ifng, Il17a, and Ccl5) at 30 d post-injury. Of note, mice treated with nasal aCD3 showed upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf), a neurotrophin that has a critical role in neuronal survival and is involved in synaptic plasticity, learning and memory62, compared with the TBI-iso control, at 1 month post-injury (Extended Data Fig. 6c).

与小胶质细胞转录组数据一致,通过同侧半球分选小胶质细胞(图 3h )及脑组织(扩展数据图 6c )的反转录定量 PCR(RT-qPCR)显示:与 TBI-iso 对照组相比,鼻腔给予 aCD3 治疗在损伤后 7 天同时提升了小胶质细胞和脑组织中抗炎细胞因子 Il10 的表达水平。此外,该治疗在损伤后 30 天显著降低了小胶质细胞(Clec7a、Tlr2、Il1b、Tnf、Cd86 和 Il18)与脑组织(Il6、Tnf、Ifng、Il17a 和 Ccl5)中多种促炎标志物的表达。值得注意的是,损伤后 1 个月时(扩展数据图 6c ),鼻腔 aCD3 治疗组小鼠相比 TBI-iso 对照组显示出脑源性神经营养因子(Bdnf)的上调——这种神经营养素对神经元存活至关重要,并参与突触可塑性、学习与记忆过程 62 。

To further investigate whether delaying the therapeutic window of nasal anti-CD3 to 3 d post-injury would still modulate the microglial transcriptomic profile at 30 d post-injury, we performed bulk RNA-seq on isolated microglia from mice treated with nasal aCD3 or isotype control from day 3 to day 30 (early treatment) post-injury (Supplementary Table 2). We found that the early treatment paradigm also modulated the microglial transcriptomic signature in the TBI-aCD3 group toward the sham-iso phenotype (Extended Data Fig. 6d) and was associated with decreased expression of several proinflammatory and DAM or MGnD genes (Lpl, Lyz1, Nfkbia, Irgm1, Lyz2 and Apoe) (Extended Data Fig. 6e). Consistent with this, GSEA analysis revealed that the early nasal aCD3 treatment paradigm was also associated with downregulation in several inflammatory response and immune response-related pathways compared with TBI-iso (Extended Data Fig. 6f). In line with these results, RT–qPCR of ipsilateral brain tissue demonstrated a reduction in several proinflammatory genes including Il6, Il18 and Tnf in TBI-aCD3 compared with TBI-iso controls (Extended Data Fig. 6g).

为进一步探究伤后 3 天延迟给予鼻用抗 CD3 单抗治疗是否仍能调控伤后 30 天小胶质细胞的转录组特征,我们对伤后第 3 至 30 天接受鼻用 aCD3 或同型对照(早期治疗组)的小鼠分离小胶质细胞进行批量 RNA 测序(补充表 2 )。研究发现早期治疗模式同样使 TBI-aCD3 组的小胶质细胞转录特征向假手术-同型对照组表型转变(扩展数据图 6d ),并伴随多种促炎基因及 DAM/MGnD 相关基因(Lpl、Lyz1、Nfkbia、Irgm1、Lyz2 和 Apoe)表达下调(扩展数据图 6e )。与此一致的是,GSEA 分析显示相较于 TBI-同型对照组,早期鼻用 aCD3 治疗方案还导致多种炎症反应和免疫反应相关通路下调(扩展数据图 6f )。与这些结果相印证,同侧脑组织的 RT-qPCR 检测显示,相比 TBI-同型对照组,TBI-aCD3 组中包括 Il6、Il18 和 Tnf 在内的多个促炎基因表达降低(扩展数据图 6g )。

To assess the effect of nasal aCD3 treatment on microglia inflammation in female mice after severe TBI, we performed bulk RNA-seq on sorted microglia at 30 d post-injury (Supplementary Table 2). We found a similar therapeutic effect in female mice with the TBI-aCD3 microglial transcriptomic profile reverting to that of sham mice, associated with a reduced inflammatory and DAM or MGnD profile relative to TBI-iso mice controls (Extended Data Fig. 6h,i). RT–qPCR of ipsilateral brain tissue showed consistent findings (Extended Data Fig. 6j). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that nasal aCD3 shifts microglia from a pathogenic, disease-associated phenotype to a beneficial, homeostatic phenotype.

为评估鼻腔 aCD3 治疗对雌性小鼠严重 TBI 后小胶质细胞炎症的影响,我们在损伤后 30 天对分选的小胶质细胞进行了批量 RNA 测序(补充表 2 )。研究发现雌性小鼠具有相似治疗效果,TBI-aCD3 组小胶质细胞转录组特征恢复至假手术组水平,相较于 TBI-iso 对照组表现出炎症反应及 DAM/MGnD 特征减弱(扩展数据图 6h,i )。同侧脑组织 RT-qPCR 结果与此一致(扩展数据图 6j )。综上表明,鼻腔 aCD3 能使小胶质细胞从致病性、疾病相关表型转变为有益的内稳态表型。

Nasal aCD3 increases microglia phagocytosis in an IL-10-dependent manner

鼻腔给予 aCD3 通过 IL-10 依赖性途径增强小胶质细胞吞噬功能

Acute brain injury leads to neuronal cell death and the release of substantial amounts of myelin and cell debris, which subsequently trigger a persistent and intense inflammatory response that may impede neurological recovery. Microglia and macrophages play an important role in debris removal and modulating the immune response post-injury20. However, uncontrolled phagocytosis may lead to progressive brain damage and worsening cognitive and memory impairments63. We found that TBI-aCD3-treated animals had increased upregulation in biological pathways involved in regulation of phagocytosis (Fig. 3e) and a distinct upregulated phagocytic signature at 7 d post-injury (Fig. 4a), with increased expression of several key microglial phagocytosis regulators at 30 d post-TBI, including Mertk64, Sirpa65 and Tlr4 (ref. 66), compared with TBI-iso microglia (Supplementary Table 2). To functionally assess the phagocytic capacity of microglia after TBI (with and without nasal aCD3 treatment), we performed an in vivo experiment in which the TBI-induced lesion was injected with either labeled apoptotic neurons or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on day 6 post-injury for 16 h and on day 7 post-injury for 4 h post-injection experiments (Fig. 4b). In line with our microglial transcriptomic data, aCD3-treated animals had higher microglial phagocytic capacity to uptake apoptotic neurons at both 4 and 16 h post-injection compared with the TBI-iso group (Fig. 4c,d and Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). To elucidate the mechanism by which nasal aCD3 enhanced microglial phagocytic capacity after TBI, we performed bulk RNA-seq on phagocytic and nonphagocytic microglia isolated at 4 and 16 h post-injection from TBI-iso and TBI-aCD3 groups at 7 d post-TBI (Supplementary Table 3). At 4 h post-injection, we observed a distinct microglial transcriptomic signature for phagocytic TBI-aCD3 microglia, characterized by the upregulation of several key phagocytosis genes (Fig. 4e). Compared with nonphagocytic TBI-iso microglia, phagocytic TBI-aCD3 microglia were associated with increased expression of genes involved in the recognition and engulfment (eat me and find me signals) of apoptotic cells and debris (Mertk67, Mrc1 (ref. 68), Abca1 (ref. 67), Lrp1 (ref. 67), and Stab1 (ref. 69)), digestion and degradation of engulfed material including lysosomal machinery (Rab27a70, Smcr8 (ref. 71), Clec16a72, and Vps8 (ref. 73)), lipid metabolism (Apoc1 (ref. 74), Olr1 (ref. 75) and Ldlr76), cytoskeleton dynamics pathways (Myo1e77) and regulation of microglial phagocytosis (Tspo78, Qk79 and Pik3cg80) (Fig. 4e,f and Supplementary Table 3). Consistent with these findings, GSEA analysis of phagocytic TBI-aCD3 microglia compared with nonphagocytic TBI-iso microglia showed enrichment for pathways involved in phagocytosis, along with other pathways pertinent for the phagocytic process such as endocytosis, pattern recognition and cell migration, all of which were not upregulated in the phagocytic TBI-iso microglia (Fig. 4g). In addition, compared with phagocytic TBI-iso microglia, phagocytic TBI-aCD3 microglia had increased upregulation of antigen presentation and IL-10 pathways (Fig. 4h). IPA analysis revealed IL-10 as a top regulator and signaling pathway in aCD3-treated phagocytic microglia post-TBI (Fig. 4h,i). We found a similar pattern of increased expression of phagocytosis machinery-related genes and pathways at 16 h post-injection (Extended Data Fig. 7c) and also observed that phagocytic TBI-aCD3 microglia had a more homeostatic and a less inflammatory (disease-associated) profile compared with phagocytic TBI-iso microglia (Extended Data Fig. 7d,e and Supplementary Table 3).

急性脑损伤会导致神经元细胞死亡并释放大量髓鞘和细胞碎片,这些物质随后会引发持续而强烈的炎症反应,可能阻碍神经功能恢复。小胶质细胞和巨噬细胞在损伤后清除碎片及调节免疫反应中起重要作用 20 。然而不受控制的吞噬作用可能导致进行性脑损伤及认知记忆功能恶化 63 。我们发现 TBI-aCD3 治疗组动物在吞噬作用调控相关生物通路上调增加(图 3e ),并在损伤后 7 天呈现显著上调的吞噬特征(图 4a ),与 TBI-iso 组小胶质细胞相比,损伤后 30 天多个关键小胶质细胞吞噬调控因子(包括 Mertk 64 、Sirpa 65 和 Tlr4(参考文献 66 ))表达增加(补充表 2 )。 为功能性评估创伤性脑损伤(TBI)后小胶质细胞的吞噬能力(含/不含鼻腔 aCD3 治疗),我们进行了体内实验:在损伤后第 6 天向 TBI 病灶注射标记的凋亡神经元或磷酸盐缓冲液(PBS)持续 16 小时,并于损伤后第 7 天进行注射后 4 小时实验(图 4b )。与小胶质细胞转录组数据一致,与 TBI-iso 组相比,aCD3 治疗组动物在注射后 4 小时和 16 小时均表现出更强的凋亡神经元摄取能力(图 4c,d 及扩展数据图 7a,b )。为阐明鼻腔 aCD3 增强 TBI 后小胶质细胞吞噬能力的机制,我们对 TBI 后 7 天从 TBI-iso 组和 TBI-aCD3 组分离的吞噬性与非吞噬性小胶质细胞进行了批量 RNA 测序(补充表 3 )。注射后 4 小时,我们观察到吞噬性 TBI-aCD3 小胶质细胞具有独特的转录组特征,表现为多个关键吞噬基因的上调(图 4e )。 与非吞噬型的 TBI-iso 小胶质细胞相比,吞噬型 TBI-aCD3 小胶质细胞表现出以下基因表达上调:参与凋亡细胞和碎片识别与吞噬("吃我"和"找我"信号)的基因(Mertk 67 、Mrc1(参考文献 68 )、Abca1(参考文献 67 )、Lrp1(参考文献 67 )和 Stab1(参考文献 69 ))、被吞噬物质的消化降解相关基因(包括溶酶体机制相关基因 Rab27a 70 、Smcr8(参考文献 71 )、Clec16a 72 和 Vps8(参考文献 73 ))、脂质代谢相关基因(Apoc1(参考文献 74 )、Olr1(参考文献 75 )和 Ldlr 76 )、细胞骨架动态通路相关基因(Myo1e 77 )以及小胶质细胞吞噬调控相关基因(Tspo 78 、Qk 79 和 Pik3cg 80 )(图 4e,f 和补充表 3 )。与这些发现一致的是,GSEA 分析显示吞噬型 TBI-aCD3 小胶质细胞相较于非吞噬型 TBI-iso 小胶质细胞在吞噬作用相关通路上呈现富集,同时还富集了与吞噬过程相关的其他通路如内吞作用、模式识别和细胞迁移——这些通路在吞噬型 TBI-iso 小胶质细胞中均未出现上调(图 4g )。 此外,与吞噬型 TBI-iso 小胶质细胞相比,吞噬型 TBI-aCD3 小胶质细胞的抗原呈递和 IL-10 通路上调更为显著(图 4h )。IPA 分析显示 IL-10 是 TBI 后 aCD3 处理吞噬型小胶质细胞中的顶级调节因子和信号通路(图 4h,i )。我们在注射后 16 小时也发现了吞噬机制相关基因和通路表达增加的相似模式(扩展数据图 7c ),并观察到与吞噬型 TBI-iso 小胶质细胞相比,吞噬型 TBI-aCD3 小胶质细胞具有更稳态且炎症(疾病相关)特征更弱的表型(扩展数据图 7d,e 及补充表 3 )。

Fig. 4. Nasal aCD3 increased microglial phagocytic capacity after TBI in an IL-10-dependent manner.

图 4. 鼻内给予 aCD3 通过 IL-10 依赖性方式增强 TBI 后小胶质细胞的吞噬能力

a, Heatmap of microglial phagocytosis genes 7 d after TBI. Genes identified with FDR-corrected P < 0.05 using DESeq2 analysis are indicated by an asterisk (two-sided LRT, n = 4 mice per group). Genes were identified from the GOBP term phagocytosis and microglial phagocytosis genes51,61. b, Schematic presenting a phagocytosis functional study (created with BioRender.com). c, Immunofluorescence of lesion (7 d post-TBI) for apoptotic neurons (blue) and P2ry12 (red) showing engulfment of apoptotic neurons by P2ry12. Scale bars, 100 μm and 50 μm for the enlarged image. d, Phagocytosis experiment where mice were injected with labeled apoptotic neurons and sacrificed 4 h post-injection. The gating strategy shows phagocytic positive microglia and data are shown as box plots (min., max., IQR, median) and n = 5 mice per group were used. Data were analyzed by two-sided, unpaired Student’s t-test. e, Clustered heatmap of DEGs of aggregated samples for phagocytic (+P) and nonphagocytic (−P) microglia 7 d post-TBI and 4 h post-injection of apoptotic neurons identified using DESeq2 analysis (two-sided LRT, n = 3-4 mice per group, FDR-corrected P < 0.05). f, Bar plots with log2(fold-changes) of genes from e pertinent to microglial phagocytosis and related functions in the following comparisons: TBI-iso (+P) versus TBI-iso (−P) and TBI-aCD3 (+P) versus TBI-Iso (−P). g, GSEA analysis of GOBP 7 d post-TBI and 4 h post-injection of apoptotic neurons based on pairwise comparisons: TBI-iso (+P) versus TBI-Iso (−P), TBI-aCD3 (+P) versus TBI-Iso (−P) and TBI-aCD3 (−P) versus TBI-Iso (−P). The asterisk indicates enriched terms (q-value < 0.05). h, Selected top canonical pathways from IPA analysis of DEGs in phagocytic TBI-aCD3 microglia compared with phagocytic and nonphagocytic TBI-iso microglial groups at 7 d post-TBI and 4 h post-injection of apoptotic neurons. i, Predicted upstream regulator in TBI-aCD3 (+P) versus TBI-iso (−P). j, Phagocytosis experiment with similar design to b. Data are shown as box plots (min., max., IQR, median) and n = 5 mice per group were used. The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. All data are biological replicates and represent two independent experiments.

a. TBI 后 7 天小胶质细胞吞噬基因热图。经 DESeq2 分析确定 FDR 校正 P 值<0.05 的基因以星号标注(双侧似然比检验,每组 n=4 只小鼠)。基因选自 GOBP 术语"吞噬作用"及小胶质细胞吞噬基因集 51,61 。

b. 吞噬功能研究示意图(使用 BioRender.com 制作)。

c. TBI 后 7 天损伤区免疫荧光染色显示凋亡神经元(蓝色)与 P2ry12(红色),呈现 P2ry12+细胞对凋亡神经元的吞噬现象。比例尺:主图 100μm,放大图 50μm。

d. 吞噬实验:注射标记凋亡神经元 4 小时后处死小鼠。流式设门策略显示吞噬阳性小胶质细胞,数据以箱线图呈现(最小值、最大值、四分位距、中位数),每组 n=5 只小鼠。采用双侧非配对 t 检验进行数据分析。 e. 采用 DESeq2 分析(双侧 LRT,每组 3-4 只小鼠,FDR 校正 P<0.05)鉴定的创伤性脑损伤(TBI)后 7 天及凋亡神经元注射后 4 小时,吞噬性(+P)与非吞噬性(-P)小胶质细胞聚合样本差异表达基因(DEGs)的聚类热图。f. 柱状图显示图 e 中与小胶质细胞吞噬及相关功能相关基因的 log2(倍数变化),比较组为:TBI-iso(+P) vs TBI-iso(-P)及 TBI-aCD3(+P) vs TBI-Iso(-P)。g. 基于配对比较的基因集富集分析(GSEA):TBI-iso(+P) vs TBI-Iso(-P)、TBI-aCD3(+P) vs TBI-Iso(-P)及 TBI-aCD3(-P) vs TBI-Iso(-P)在 TBI 后 7 天及凋亡神经元注射后 4 小时的 GOBP 分析。星号标注富集条目(q 值<0.05)。h. IPA 分析中从 TBI-aCD3 吞噬性小胶质细胞与 TBI-iso 吞噬性/非吞噬性小胶质细胞组(TBI 后 7 天及凋亡神经元注射后 4 小时)的 DEGs 筛选出的典型通路。i. TBI-aCD3(+P) vs TBI-iso(-P)中预测的上游调控因子。j. 实验设计与图 b 相似的吞噬功能检测。数据以箱线图呈现(最小值、最大值、四分位距、中位数),每组 n=5 只小鼠。 数据采用单因素方差分析(ANOVA)结合 Tukey 多重比较法进行统计分析。所有数据均为生物学重复样本,代表两项独立实验。

Extended Data Fig. 7. Nasal anti-CD3 increases expression of phagocytosis machinery at 16 hours post injection of apoptotic neurons.

扩展数据图 7. 鼻腔给予抗 CD3 单抗可提升注射凋亡神经元 16 小时后小胶质细胞吞噬机制相关蛋白的表达水平。

(a) Schematic presenting phagocytosis functional study. Created with BioRender.com. (b)

In-vivo phagocytosis functional experiment where mice were injected with labelled apoptotic neurons and sacrificed 16 h post injection. Gating strategy showing phagocytic positive microglia in TBI-Iso and TBI-aCD3 animals. Data shown as box plots (min, max, interquartile range, median) and n = 5 mice/group were used. Data was analyzed by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. (c) Clustered heatmap of select DEGs of aggregated samples for phagocytic ( + P) and non-phagocytic (-P) microglia at 7 days following TBI and 16 hours post-injection of apoptotic neurons using DESeq2 analysis (two-sided likelihood ratio test, n = 5-6 mice/group, FDR-corrected P < 0.05). Identified genes pertinent to microglial phagocytosis and related functions are visualized through bar plots with log2-fold changes in phagocytic TBI-aCD3 microglia compared to non-phagocytic TBI-Iso microglia. (d) GSEA analysis of GO Biological Process (BP) comparing phagocytic TBI-aCD3 microglia to phagocytic TBI-Iso microglia at 7 days following TBI and 16 hours post-injection of apoptotic neurons. NES, normalized enrichment score. (e) Bar plots of select microglial homeostatic and neurodegenerative microglia (MGnD) markers in phagocytic TBI-aCD3 microglia compared to phagocytic TBI-Iso microglia at 7 days following TBI and 16 hours post-injection of apoptotic neurons. DEGs indicated with an asterisk: FDR-corrected P < 0.05; DEGs indicated with “*P”: P < 0.05 (DESeq2 analysis, two-sided Wald test, n = 5 mice/group). (f) Gating strategy showing how phagocytic microglia cells were identified. All data are biological replicates and are representative from two independent experiments. n.s. = non-significant.

(a) 吞噬功能研究示意图。使用 BioRender.com 创建。(b) 体内吞噬功能实验:向小鼠注射标记的凋亡神经元,注射 16 小时后处死。门控策略显示 TBI-Iso 组和 TBI-aCD3 组中具有吞噬活性的小胶质细胞。数据以箱线图呈现(最小值、最大值、四分位距、中位数),每组 n=5 只小鼠。采用双尾非配对 Student t 检验分析数据。(c) 通过 DESeq2 分析(双尾似然比检验,每组 n=5-6 只小鼠,FDR 校正 P<0.05)获得的 TBI 后 7 天及凋亡神经元注射 16 小时后吞噬性(+P)与非吞噬性(-P)小胶质细胞差异表达基因(DEGs)聚类热图。与小胶质细胞吞噬功能相关的关键基因通过条形图展示,显示吞噬性 TBI-aCD3 小胶质细胞相较于非吞噬性 TBI-Iso 小胶质细胞的 log2 倍数变化。(d) TBI 后 7 天及凋亡神经元注射 16 小时时,吞噬性 TBI-aCD3 与吞噬性 TBI-Iso 小胶质细胞的 GO 生物过程(BP)基因集富集分析(GSEA)。NES:标准化富集分数。 (e) 条形图显示创伤性脑损伤(TBI)后 7 天及凋亡神经元注射 16 小时后,吞噬性 TBI-aCD3 小胶质细胞与吞噬性 TBI-Iso 小胶质细胞中选定的小胶质细胞稳态标志物及神经退行性小胶质细胞(MGnD)标志物的表达差异。标有星号的差异表达基因(DEGs):FDR 校正后 P 值<0.05;标有"*P"的 DEGs:P 值<0.05(DESeq2 分析,双侧 Wald 检验,每组 n=5 只小鼠)。(f) 展示吞噬性小胶质细胞鉴定策略的门控方案。所有数据均为生物学重复,结果来自两次独立实验。n.s.表示无统计学意义。

To investigate the role of IL-10 in the regulation of microglia phagocytic capacity after TBI, we repeated the in vivo microglia phagocytosis assay using IL-10 knockout (KO) mice (Fig. 4j). We found that the increased phagocytic capacity of TBI-aCD3 microglia at 4 h post-injection was significantly attenuated in the IL-10 KO TBI-aCD3 microglial group. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that nasal aCD3 treatment increases the phagocytic machinery of microglia after acute TBI, in an IL-10-dependent manner. In addition, we found that the phagocytic capacity of wild-type (WT) TBI-iso microglia was significantly reduced in the IL-10 KO TBI-iso microglia group, demonstrating the importance of IL-10 in microglial phagocytic function after TBI.

为探究 IL-10 在创伤性脑损伤(TBI)后调控小胶质细胞吞噬功能中的作用,我们使用 IL-10 基因敲除(KO)小鼠重复了体内小胶质细胞吞噬实验(图 4j )。研究发现,在 IL-10 KO TBI-aCD3 组中,注射后 4 小时 TBI-aCD3 小胶质细胞增强的吞噬能力显著减弱。这些结果共同表明,鼻腔给予 aCD3 通过 IL-10 依赖性机制增强了急性 TBI 后小胶质细胞的吞噬功能。此外,我们发现野生型(WT)TBI-iso 组小胶质细胞的吞噬能力在 IL-10 KO TBI-iso 组中显著降低,证实了 IL-10 对 TBI 后小胶质细胞吞噬功能的关键作用。

Nasal aCD3 ameliorates TBI outcomes via IL-10/IL-10R signaling in microglia

鼻腔给予 aCD3 通过小胶质细胞中 IL-10/IL-10R 信号通路改善 TBI 预后

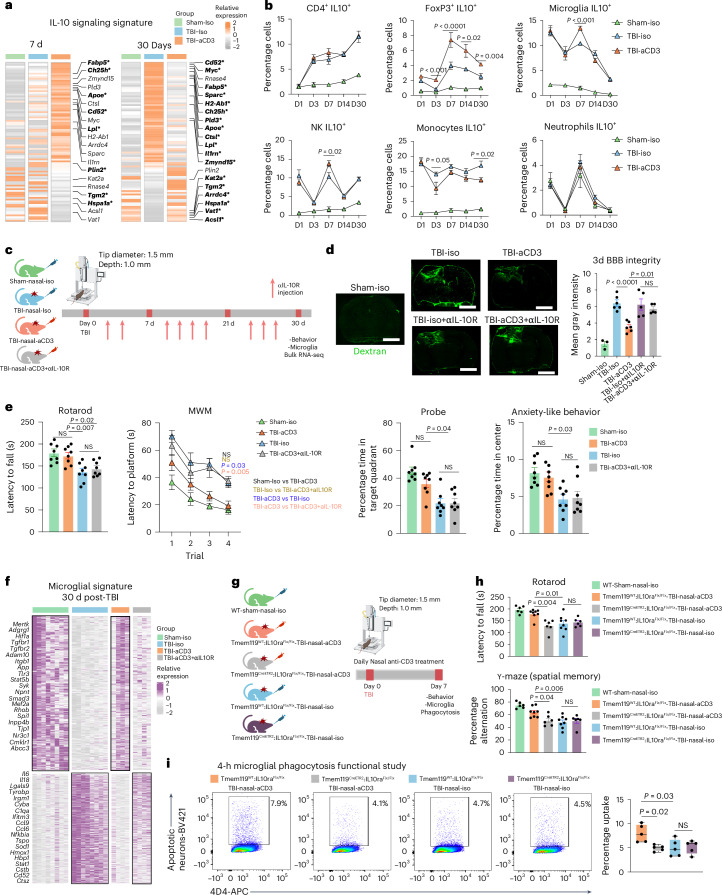

IL-10 is a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine produced by Treg cells that acts on many cell types as a result of the presence of IL-10 receptor (IL-10R) on almost all hematopoietic cells81. IL-10 signaling is critical to maintain microglia under a homeostatic phenotype, because genetic depletion of IL-10 under proinflammatory conditions results in increased release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines82. We found a clear upregulation of the microglial IL-10-cytokine gene expression signature in TBI-aCD3 microglia group at 7 days post-CCI as compared to Sham-Iso and TBI-Iso controls (Fig. 5a). We also found that nasal aCD3 induced IL-10-secreting Treg cells (from day 3 to day 30 post-injury) (Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 8a) and increased IL-10 expression in both microglia and brain tissue derived from the site of injury (Fig. 3h and Extended Data Fig. 6c). We then investigated whether IL-10 played a role in the beneficial effects of nasal aCD3 by administering anti-IL-10R (aIL-10R)-blocking antibody intraperitoneally (i.p.) every 3 d post-injury (Fig. 5c) and investigating the behavioral outcomes and BBB disruption in sham-iso, TBI-iso, TBI-aCD3 and TBI-aCD3+aIL-10R groups. We found that the improvements in BBB disruption (Fig. 5d) and motor coordination functions, spatial memory and anxiety-like behavior observed in TBI-aCD3 were abrogated by blocking IL-10R (TBI-aCD3+aIL-10R group) (Fig. 5e).

IL-10 是一种由 T reg 细胞产生的强效抗炎细胞因子,由于几乎所有造血细胞 81 表面都存在 IL-10 受体(IL-10R),其可作用于多种细胞类型。IL-10 信号传导对维持小胶质细胞稳态表型至关重要,因为在促炎条件下 IL-10 基因缺失会导致促炎细胞因子和趋化因子释放增加 82 。我们发现,与 Sham-Iso 和 TBI-Iso 对照组相比,CCI 术后 7 天的 TBI-aCD3 小胶质细胞组中,小胶质细胞 IL-10 细胞因子基因表达特征明显上调(图 5a )。研究还发现鼻腔给予 aCD3 可诱导 IL-10 分泌型 T reg 细胞(从损伤后第 3 天持续至第 30 天)(图 5b 及扩展数据图 8a ),并提高损伤部位小胶质细胞和脑组织中的 IL-10 表达(图 3h 及扩展数据图 6c )。随后我们通过腹腔注射(i.p.)抗 IL-10R(aIL-10R)阻断抗体(每 3 天一次)来研究 IL-10 是否参与鼻腔 aCD3 的治疗作用(图 5c )并研究假手术组(sham-iso)、创伤性脑损伤组(TBI-iso)、抗 CD3 单抗治疗组(TBI-aCD3)及抗 CD3 单抗联合 IL-10 受体阻断组(TBI-aCD3+aIL-10R)的行为学结果与血脑屏障破坏情况。我们发现,抗 CD3 单抗治疗组(TBI-aCD3)在改善血脑屏障破坏(图 5d )、运动协调功能、空间记忆及焦虑样行为方面的效果,均被 IL-10 受体阻断剂(TBI-aCD3+aIL-10R 组)所抵消(图 5e )。

Fig. 5. Nasal aCD3 ameliorates TBI microglial inflammation and functional outcomes in an IL-10-dependent manner.

图 5. 鼻腔给予 aCD3 通过 IL-10 依赖性途径改善 TBI 小胶质细胞炎症并促进功能恢复

a, Heatmap of genes of aggregated samples involved in the IL-10 pathway for microglia at 7 and 30 d post-TBI. Genes identified with an FDR-corrected P < 0.05 using DESeq2 analysis are emboldened and indicated by an asterisk (two-sided LRT, n = 4 mice per group). Genes were identified from the literature109. b, IL-10 expression (flow cytometry) in different cells at different time points post-TBI and treatment in the ipsilateral hemisphere (sham-iso n = 4, TBI-iso n = 6, TBI-aCD3 n = 6), analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons for individual time points. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. NK, natural killer cell. c, Experimental timeline of anti-IL-10R-blocking mAbs (aIL-10R) (created with BioRender.com). d, Dextran 70-kDa (green) for measurement of BBB permeability (3 d post-TBI). Scale bars, 1,000 μm. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (sham-iso n = 3, n = 6 for the rest of the groups), analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. e, Behavioral testing (rotarod, MWM, probe trial, OF for anxiety-like behavior). The MWM was analyzed by two-factor, repeated-measures, two-way ANOVA (group × time) and the others by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (n = 8 mice per group). f, Clustered heatmap DEGs at 30 d post-TBI identified using DESeq2 analysis (two-sided LRT, n = 4–8 mice per group, FDR-corrected P < 0.05). The microglial data at 30 d post-TBI from Fig. 3c were integrated. g, Experimental timeline for the microglia-specific IL-10ra KO (created with BioRender.com). h, Behavioral testing of rotarod and Y-maze assessed between the groups. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (WT sham-nasal-iso n = 6, Tmem119WT:IL-10raFlx/Flx-TBI-Nasal-aCD3 n = 8, Tmem119CreETR2:IL-10raFlx/Flx-TBI-Nasal-aCD3 n = 6, Tmem119WT:IL-10raFlx/Flx-TBI-nasal-iso n = 8, Tmem119 CreETR2:IL-10raFlx/Flx-TBI-nasal-iso n = 6). Analysis was by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. i, Phagocytosis experiment with a similar design to Fig. 4b. Data are shown as box plots (min., max., IQR, median; n = 5 mice per group), analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons. All data are biological replicates and represent two independent experiments.

a. TBI 后 7 天和 30 天小胶质细胞 IL-10 通路相关基因的样本聚合热图。经 DESeq2 分析(双侧 LRT,每组 n=4 只小鼠)确定 FDR 校正 P 值<0.05 的基因以加粗字体标出并附星号标记。基因筛选依据文献 109 。b. 采用流式细胞术检测 TBI 后不同时间点及治疗组损伤同侧半球 IL-10 表达(假手术组同型对照 n=4,TBI 组同型对照 n=6,TBI-aCD3 组 n=6),各时间点数据通过单因素方差分析结合 Tukey 多重比较检验。数据以均值±标准误表示。NK:自然杀伤细胞。c. 抗 IL-10R 阻断单抗(aIL-10R)实验时间轴(使用 BioRender.com 制作)。d. 70-kDa 右旋糖酐(绿色)检测 TBI 后 3 天血脑屏障通透性。比例尺:1,000 μm。数据以均值±标准误表示(假手术组同型对照 n=3,其余组 n=6),采用单因素方差分析结合 Tukey 多重比较检验。e. 行为学测试(转棒实验、Morris 水迷宫、探测试验、旷场焦虑样行为检测)。Morris 水迷宫采用双因素重复测量双因素方差分析(组别×时间),其余测试采用单因素方差分析结合 Tukey 多重比较检验。 数据以均值±标准误表示(每组 n=8 只小鼠)。f、采用 DESeq2 分析鉴定的 TBI 后 30 天差异表达基因聚类热图(双侧似然比检验,每组 n=4-8 只小鼠,FDR 校正 P<0.05)。整合了图 3c 中 TBI 后 30 天的小胶质细胞数据。g、小胶质细胞特异性 IL-10ra 敲除实验时间线(使用 BioRender.com 创建)。h、各组间旋转棒和 Y 迷宫行为学测试结果。数据以均值±标准误表示(WT 假手术-鼻腔同型对照 n=6,Tmem119 WT :IL-10ra Flx/Flx -TBI-鼻腔 aCD3 n=8,Tmem119 CreETR2 :IL-10ra Flx/Flx- TBI-鼻腔 aCD3 n=6,Tmem119 WT :IL-10ra Flx/Flx -TBI-鼻腔同型对照 n=8,Tmem119 CreETR2 :IL-10ra Flx/Flx- TBI-鼻腔同型对照 n=6)。采用单因素方差分析及 Tukey 多重比较。i、吞噬实验设计与图 4b 类似。数据以箱线图表示(最小值、最大值、四分位距、中位数;每组 n=5 只小鼠),采用单因素方差分析及 Tukey 多重比较。所有数据均为生物学重复,代表两次独立实验。

Extended Data Fig. 8. Gating strategy of IL-10 production, tamoxifen induced microglia specific IL10ra reduction in gene expression, and FoxP3(GFP)+ gating strategy.

扩展数据图 8. IL-10 产生的门控策略、他莫昔芬诱导的小胶质细胞特异性 IL10ra 基因表达降低,以及 FoxP3(GFP)+门控策略。

(a) Gating strategy for IL-10 expression on CD4 + , FoxP3 + , 4D4+ microglia, NK1.1 + , Ly6C + , and Ly6G+ cell and their fluorescence minus one (FMO) control. (b) Bar plot of Quantitative PCR of microglia sorted from the ipsilateral hemisphere at 7 days post TBI for microglia specific IL-10ra knockout Tmem119CreETR2:IL-10raFlx/Flx and their littermate controls Tmem119WT:IL-10raFlx/Flx. Mice were treated with tamoxifen for 5 straight days and were given a 2-week rest period before TBI. Expression was normalized to GAPDH. Data shown as mean ± SEM, n = 3 mice/group. Data was analyzed by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. The data are biological replicates and are representative from three independent experiments. (c) Gating strategy showing CD4+FoxP3 GFP+ and the population of CD4+FoxP3 GFP- from the spleen/cLN that was selected for the adoptive transfer experiments in Fig. 6 and Extended Data Fig. 9.

(a) CD4+、FoxP3+、4D4+小胶质细胞、NK1.1+、Ly6C+及 Ly6G+细胞中 IL-10 表达的设门策略及其荧光减一(FMO)对照。(b) TBI 后 7 天从同侧半球分选的小胶质细胞定量 PCR 柱状图,显示小胶质细胞特异性 IL-10ra 敲除组 Tmem119 CreETR2 :IL-10ra Flx/Flx 及其同窝对照 Tmem119 WT :IL-10ra Flx/Flx 。小鼠连续 5 天接受他莫昔芬处理,TBI 前休息 2 周。表达量以 GAPDH 标准化。数据显示为均值±SEM,n=3 只/组。采用双侧非配对 Student t 检验分析。数据为生物学重复,代表三次独立实验。(c) 显示 CD4 + FoxP3 GFP + 的设门策略及来自脾脏/颈淋巴结的 CD4 + FoxP3 GFP - 细胞群,该群体被选用于图 6 和扩展数据图 9 中的过继转移实验。

We next investigated the impact of blocking IL-10R on the microglial inflammatory transcriptomic profile by performing RNA-seq on sorted microglia from the ipsilateral hemisphere of the brain (Extended Data Fig. 6a) at 1 month post-CCI (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 4). We found that the modulatory effect of nasal aCD3 on microglia was abrogated by blocking IL-10 as shown in the microglial heatmap signature (Fig. 5f). At 1 month post-CCI, similar to the transcriptomic signature of TBI-iso control, microglia from the TBI-aCD3+aIL-10R group had a more proinflammatory profile compared with sham-iso and the TBI-aCD3 group and was associated with decreased expression of homeostatic markers such as Mertk, Tgfbr2, Atp8a2, and Adgrg1 (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Table 4).

我们随后通过 RNA 测序研究了阻断 IL-10R 对损伤同侧大脑半球小胶质细胞炎症转录组特征的影响(扩展数据图 6a ),检测时间为 CCI 术后 1 个月(图 3b 和补充表 4 )。小胶质细胞热图特征显示(图 5f ),鼻腔给予 aCD3 对小胶质细胞的调节作用会因 IL-10 阻断而消除。CCI 术后 1 个月,与 TBI-iso 对照组相似,TBI-aCD3+aIL-10R 组的小胶质细胞较假手术组和 TBI-aCD3 组表现出更强的促炎特征,同时伴随稳态标志物(如 Mertk、Tgfbr2、Atp8a2 和 Adgrg1)表达水平下降(图 5f 和补充表 4 )。

We hypothesized that the beneficial effect of the Treg cells induced by nasal aCD3 was dependent on IL10R signaling in microglia. We thus investigated this hypothesis by using IL-10Rflox/floxTmem119CreETR2 conditional and tamoxifen-induced KO mice and littermate controls (Extended Data Fig. 8b). We investigated the effects of microglial IL-10R ablation on the behavioral and microglial phagocytic capacity at 7 d post-TBI (Fig. 5g). We found that tamoxifen-treated TBI-aCD3-IL-10Rflox/floxTmem119CreETR2 mice exhibited worse motor and cognitive outcomes (Fig. 5h) and reduced microglial phagocytic capacity (Fig. 5i) compared with tamoxifen-treated TBI-aCD3 littermate controls, further supporting the role for IL-10 in modulating the microglial gene signature after nasal aCD3 treatment. Taken together, these data clearly demonstrate a critical role for IL-10/IL-10R signaling in augmenting microglial phagocytic capacity and ameliorating disease in TBI.

我们假设鼻腔给予 aCD3 诱导的 T reg 细胞的神经保护作用依赖于小胶质细胞中的 IL10R 信号通路。为此,我们使用 IL-10R flox/flox Tmem119 CreETR2 条件性敲除和他莫昔芬诱导的基因敲除小鼠及其同窝对照进行验证(扩展数据图 8b )。研究发现在 TBI 后第 7 天,小胶质细胞 IL-10R 缺失对行为学表现和小胶质细胞吞噬功能的影响(图 5g )。与他莫昔芬处理的 TBI-aCD3 同窝对照组相比,他莫昔芬处理的 TBI-aCD3-IL-10R flox/flox Tmem119 CreETR2 小鼠表现出更差的运动及认知功能(图 5h )和降低的小胶质细胞吞噬能力(图 5i ),这进一步证实了 IL-10 在鼻腔 aCD3 治疗后调节小胶质细胞基因特征中的作用。综上所述,这些数据明确表明 IL-10/IL-10R 信号通路在增强小胶质细胞吞噬能力和改善 TBI 病理过程中具有关键作用。

Nasal aCD3-induced CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells ameliorate neuroinflammation and TBI outcomes

鼻腔给予 aCD3 诱导的 CD4 + FoxP3 + T reg 细胞可改善神经炎症及创伤性脑损伤预后