Abstract 摘要

Long term surface evolution of matte tin electroplating has been investigated under room temperature to understand the tin whisker mitigation by a trace amount of lead addition. No whisker growth has been observed on all the Sn–xPb samples (1 ≤ x ≤ 10 wt%), while at least 3 wt% of Pb addition is required to alter the columnar grain structure of pure Sn plating to equiaxed grains. The mitigation mechanism by such a trace amount of Pb is not caused by the grain texture control, but is due to the less inter-metallic composite (IMC) growth; the segregated Pb at the columnar grain boundaries disrupts the IMC growth, and releases Sn grain boundary migrations to relax the internal stress. This mechanism of stress relaxation and whisker growth suppression suggests that lead-free Sn plating without whisker growth can be realized by co-plating Sn with a Pb-like metal element that precipitates at the grain boundary to interfere with the IMC growth.

长期研究了室温下哑光锡电镀表面的演变,以了解微量铅添加对锡须的抑制作用。在所有 Sn–xPb 样品(1 ≤ x ≤ 10 wt%)中均未观察到锡须生长,而至少需要添加 3 wt%的铅才能改变纯锡电镀的柱状晶粒结构为等轴晶粒。这种微量铅的抑制机制并非由晶粒纹理控制引起,而是由于金属间化合物(IMC)生长减少;柱状晶粒界面的分离铅破坏了 IMC 生长,并释放锡晶粒界迁移以缓解内部应力。这种应力释放与 whisker 生长的抑制机制表明,通过与一种在晶界沉淀并干扰 IMC 生长的铅类似金属元素共镀,可实现无 whisker 生长的无铅锡镀层。

Similar content being viewed by others

其他人正在查看的类似内容

Explore related subjects

探索相关主题

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.发现来自相关领域研究人员的最新文章和新闻,这些内容是通过机器学习推荐的。

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction 1 引言

Electro or electro-less plating has been developed without lead following the recent movement for lead-free packaging of electronics devices. Lead-free plating of pure Sn, Sn–Bi, Sn–Ag and Sn–Cu have replaced the conventional Sn–Pb electro plating. However, such lead-free plating faces a risk of tin whisker growth. Tin whiskers that can grow up to a few millimeters often cause a short circuit failure in electronic components. Due to the miniaturization trend of electronic devices, a few ten micrometers length of whisker is enough to make a short circuit in fine-pitch packaging [1–4]. The tin whisker growth mechanism by internal or external mechanical stress has been reported frequently during the past decades. These reports have focused on: (1) the expansion of intermetallic compound (IMC) volume, (2) Sn grain growth at room temperature by recrystallization or by grain migration, (3) thermal stress caused by thermal expansion mismatch between plating and substrate, and (4) oxidation on plating surface accelerated by high temperature and humidity [5, 6]. To prevent tin whisker failure in electronic devices, various methods of whisker mitigation have been proposed. For example, annealing by heat treatment at 150 °C for longer than 30 min is typical for reduce whiskers at ambient storage. The heat treatment creates a uniform IMC layer at the interface between Sn plating and Cu substrate, and the uniform IMC layer hampers further IMC growth particularly along the Sn grain boundaries because of the decreased Cu diffusion rate [7–9]. Thickening the plating layer relaxes the compressive stress in tin plating to reduce the whisker density [10]. Recently, the stress relaxation mechanism of Sn–Pb alloying has been reported; the addition of lead in matte tin forms the equiaxed grain structure to reduce the residual stress of electroplating process, and is effective on Sn whisker incubation [11, 12]. And also, Sn–Pb plating eliminates Sn whisker by changing IMC growth [13]. However, the lead contents of examined in their reports were 5–40 wt%, and the similar grain structure alternation from columnar to equiaxed was found in both the cases. Thus the necessary amount of Pb has been yet unknown, and the detailed role of Pb element in the Sn grain structure as well.

电镀或无电镀工艺在电子设备无铅包装的趋势下,已开发出无铅工艺。纯锡(Sn)、锡-铋(Sn-Bi)、锡-银(Sn-Ag)和锡-铜(Sn-Cu)的无铅电镀已取代传统的锡-铅(Sn-Pb)电镀。然而,此类无铅电镀存在锡须生长的风险。锡须可生长至几毫米长,常导致电子元件短路失效。由于电子设备小型化趋势,仅几微米长的锡须即可在细间距封装中引发短路[1–4]。过去数十年间,关于锡须在内部或外部机械应力作用下的生长机制已被频繁报道。这些研究主要关注以下方面:(1) 间金属化合物(IMC)体积的膨胀,(2) 室温下锡晶粒通过再结晶或晶粒迁移导致的生长,(3) 镀层与基底之间热膨胀不匹配引起的热应力,(4) 高温高湿环境下镀层表面氧化加速[5, 6]。为防止电子设备中锡须失效,提出了多种抑制锡须的方法。例如,通过在 150°C 下热处理 30 分钟以上,可有效减少环境储存条件下的锡须生长。热处理在锡镀层与铜基底界面形成均匀的互溶相(IMC)层,该均匀 IMC 层通过降低铜扩散速率,特别是在锡晶界处,抑制了 IMC 的进一步生长[7–9]。增厚镀层可缓解锡镀层中的压应力,从而降低须状晶密度[10]。 最近,关于锡-铅合金的应力松弛机制已被报道;在锡锭中添加铅可形成等轴晶粒结构,从而降低电镀过程中的残余应力,并对锡须的萌生具有抑制作用[11, 12]。此外,Sn–Pb 电镀通过改变共析金属间化合物(IMC)的生长机制消除锡须[13]。然而,其研究中铅含量为 5–40 wt%,且两种情况下均观察到柱状晶粒结构向等轴晶粒结构的转变。因此,铅的必要添加量仍不清楚,铅元素在锡晶粒结构中的具体作用也需进一步研究。

In this study, the role of small amount of Pb addition in matt tin plating has been explored in connection with whisker growth observations for 1-year long storage under room temperature. Evolutions of the grain microstructure, surface texture, and IMC growths have frequently been observed during the storage experiment, and compared with various Pb concentrations of Sn–xPb co-electroplating where 0 ≤ x ≤ 10 wt%. The typical texture of electroplated pure Sn displays a vertical columnar structure that is prone to generate tin whiskers, while whisker mitigation has been confirmed in all the Pb added Sn plating specimens. However, our thin electro plating of Sn–xPb (x ≤ 3 wt%) displays a columnar grain structure similar to that of pure Sn, instead of the equiaxed grains that relieve compressive stress more effectively than the columnar grains [7] This means whisker suppression mechanism can be different when only 1 wt% of lead is added in tin. The present experimental research aims to clarify the unidentified mechanism of tin whisker mitigation, seeking for further possibility to Pb-free whisker mitigation methods.

在本研究中,结合室温下长达 1 年的晶须生长观察,探讨了少量 Pb 添加在亚光锡镀层中的作用。在储存实验中经常观察到晶粒微观结构、表面纹理和 IMC 生长的演变,并与 0 ≤ x ≤ 10 wt% 的各种 Pb 浓度的 Sn-xPb 共电镀进行比较。电镀纯 Sn 的典型纹理显示出垂直柱状结构,容易产生锡须,而在所有添加 Pb 的 Sn 电镀样品中都证实了晶须减少。然而,我们的 Sn-xPb (x ≤ 3 wt%) 电镀显示出类似于纯 Sn 的柱状晶粒结构,而不是比柱状晶粒更有效地缓解压应力的等轴晶粒 [ 7]这意味着当锡中仅添加 1 wt% 的铅时,晶须抑制机制可能会有所不同。本实验研究旨在阐明锡须缓解的未知机制,为无铅晶须缓解方法寻找进一步的可能性。

2 Experimental procedure 2 实验程序

Matte Sn–xPb (x = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10 wt%) were electroplated on a copper lead-frame for quad flat packaging (corresponding to CDA number C19400) sheets, using an electric current density of 5 A/cm2. The electroplating process was carried out in a 3 liter of 1 pH solution bath at 45 °C for 3 min and 10 s. After the electroplating, all the samples were cleaned with distilled water, and then dried for 20 s with a dry machine gun. Figure 1 shows a typical electroplated lead-frame specimen. The plating thickness was about 5 μm for all the samples. These samples were stored at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) for 1 year, and the growth behavior of Sn whiskers and surface changes were continuously observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-5510S, JEOL, Japan) during the test period.

使用 5 A/cm 2 的电流密度,将锍 Sn–xPb (x = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10 wt%) 电镀在用于四方扁平封装(对应于 CDA 编号 C19400)片材的铜引线框架上。电镀过程在 3 升 1 pH 溶液浴中于 45 °C 下进行 3 分钟和 10 秒。电镀后,用蒸馏水清洗所有样品,然后用干机枪干燥 20 s。图 1 显示了一个典型的电镀引线框架样品。所有样品的镀层厚度约为 5 μm。这些样品在室温 (25 ± 2 °C) 下储存 1 年,测试期间通过扫描电子显微镜 (SEM, JSM-5510S, JEOL, Japan) 连续观察 Sn 晶须的生长行为和表面变化。

The microstructure and crystal grain size of the coatings were determined by SEM observation on the surfaces, and on the cross-sections of the coatings (FE-SEM 2100, JEOL, Japan). Focused ion beam (FIB) microscope (Hitachi FB-2100, Japan) was utilized to fabricate cross-section samples of the coatings, whiskers, and hillocks, as well as FIB imaging. The distributions of Sn and Pb grains were determined at 1 μm depth from the topmost surface with using FIB. Cross section polisher (SM-09010, JEOL, Japan) of Ar ion etching was also used for cross-section sample preparations, and energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis was performed. Finally, the Sn–xPb plating layer was removed with using the etchant composed of hydrochloric acid (3 %) and nitric acid (5 %) in ethanol (92 %), and then the surface distributions of remaining IMCs were observed with field emission-scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM).

通过对表面和涂层横截面的 SEM 观察来确定涂层的微观结构和晶粒尺寸 (FE-SEM 2100,JEOL,日本)。聚焦离子束 (FIB) 显微镜(Hitachi FB-2100,日本)用于制造涂层、晶须和小丘的横截面样品,以及 FIB 成像。使用 FIB 在距最顶表面 1 μm 深度处测定 Sn 和 Pb 晶粒的分布。Ar 离子刻蚀的横截面抛光机 (SM-09010, JEOL, Japan) 也用于横截面样品制备,并进行能量色散 X 射线 (EDX) 分析。最后,使用由盐酸 (3 %) 和硝酸 (5 %) 在乙醇 (92 %) 中组成的蚀刻剂去除 Sn-xPb 电镀层,然后用场发射扫描电子显微镜 (FE-SEM) 观察剩余 IMC 的表面分布。

3 Results and discussion 3 结果与讨论

3.1 Tin whisker generation at room temperature

The surface images of as-plated matte Sn and Sn–xPb are presented in Fig. 2. All the fresh samples show flat surfaces without any whiskers or cracks. The morphologies of the topmost surfaces appear differently according to the amount of Pb addition. With increasing Pb content in Sn, the size of surface grains decreases. The small amount of Pb addition thus results in Sn grain refinement. FIB images presented in Fig. 3 display the Pb distributions under 1 μm from the top surface. The segregated Pb increases with increasing Pb content. Moreover, the average size of Sn grains is decreased with increasing Pb content as well. In particular, the grain sizes of Sn-1 % Pb are smaller than those of the pure matte Sn as seen in Fig. 3a, b. This means that the grain refinement effect starts at only 1 wt% of Pb addtion. The Pb grains are mainly located on Sn grain boundaries regardless of Pb content. Because of the negligible solubility of Pb in Sn at room temperature both the size and number of segregated Pb grains increases with increasing Pb content from 1 to 10 wt%, being consistent with the report in the literature [7].

Figure 4 shows the morphologies of all the plated samples after 24 h on room temperature storage. Short tin whiskers have been confirmed only on the pure tin surface (see Fig. 4a), while no morphological change on the plating with lead addition (Fig. 4b–f). This indicates that only 1 day is enough to generate whiskers on pure Sn even under the room temperature to relieve the residual stress accumulated in the electroplating process. The surface images after the 1 year storage are presented in Fig. 5. These SEM images indicate that Sn whiskers can grow exclusively on the pure tin electroplated surface whereas hillocks are observed instead of whiskers on the Sn–xPb plating surface irrespective of the lead content. The average density of Sn whiskers is about 2.28 counts/1,000 μm2 on pure Sn coating, while that of hillocks is less or equal to unity on all the Sn–xPb samples (see Fig. 6). The maximum length and width among all the observed tin whiskers on the pure tin surface are about 52 and 5.8 μm, respectively. The hillocks found on Sn–xPb plating surface have a width of 10.8 μm at maximum. Our frequent SEM observations have revealed that the continuous hillock growth is obvious during the first 10 days, but then gradually slows down to reach the saturation until the last observation after 1 year storage. All the lead added plating surfaces exhibit little change of surface and hillock morphology after the active growth found in the early days. This contrasts the unremitting whisker growth on pure Sn until the end of the storage tests. These observations lead us to the two possible explanations; (1) hillocks release the stress faster than tin whiskers; (2) the stress accumulation continues for longer duration in pure Sn than lead added plating. It is not obvious to identify the reason directly from these surface observations. In any case, it is noteworthy that only 1 wt% of lead addition drastically changes the stress relaxation mode from whisker growth to hillock creation.

To investigate the source of internal compressive stress, cross-sectional observations have achieved by SEM. Figure 7 shows the cross-sectional texture change during the long period storage tests: (a–d) as prepared, and (e–h) after 1 year at room temperature. At the beginning, pure Sn indicates a typical columnar structure in Fig. 7a. Both the structures of Sn–1Pb (b) and Sn–3Pb (c) appear to keep nearly columnar structure, but include some small Pb grains. In contrust, Sn–10Pb (d) exhibits a typical equiaxed grains including large Pb grains. More numbers of Sn grain boundaries becomes parallel to the substrate with increasing Pb content from 1 to 10 wt%, since Pb co-deposition significantly reduces crystallographic texture orientation in Sn by preventing the columnar growth [7, 11]. All the Sn grains found in Sn and Sn–xPb samples have bulked up after 1 year without alternating the initial grain structures.

The IMCs at interface between Sn and Cu substrate continuously grow in all the samples during the 1 year at room temperature as shown in Fig. 7e–h. In the case of pure Sn plating, IMCs grow along Sn grain boundaries. Particularly large IMC growth can be observed at the boundaries of the root grain under the stemmed tin whisker (see Fig. 7e). Such a large IMC contributes to the increase of the compressive stress around the root Sn grain, and hence the whisker needs to grow at the surface to release the accumulated stress. In contrast, the volume of IMCs after 1 year in Pb added plating are smaller than that of pure Sn plating at Sn/Cu interface and at Sn grain boundaries. Moreover, the IMC growth in the Pb added Sn samples uniformly grew over the entire interface area during the 1 year of storage. These cross-section FIB observations in Fig. 7 reveal that tin whisker growth found only on pure Sn plating surface is due to the concentrated IMCs along the grain boundaries.

Energy dispersive X-ray results in Fig. 8 show the distributions of IMCs in pure Sn plating (a) and Sn–10Pb (b) on Cu substrate after 1 year. The determined composition is Cu6Sn5. The IMC growth patterns appear different in pure Sn and in Sn–10Pb samples. The IMCs of pure Sn grew to concentrate in grain boundaries which are consistent with the FIB cross-section analysis in Fig. 7, and the uniform growth pattern in Sn–10Pb as well. The IMC growth is faster and larger in pure Sn under room temperature than that in Sn–10Pb. The back-scattered FE-SEM images in Fig. 9 display the final distributions of Sn grains, grown IMC, and segregated Pb in both pure Sn and Sn–10Pb plating samples after 1 year storage. The IMC growth along the Sn grain boundaries can be clearly seen in Fig. 9a, while the Pb grains in Sn–10Pb appear to disturb the IMC growth at the grain boundaries (see Fig. 9b). Consuming the diffused Cu atoms from the substrate, the IMC growth causes total volume increase of the plating. Larger the IMC volume, higher the compressive stress. Therefore, one can conclude that the compressive stress accumulated during the 1 year is higher in pure tin than in Sn–10Pb. This compressive stress due to the IMC growth changes the stress relaxation mode resulting in different surface morphologies such as whiskers or hillocks. This also implies that whisker needs higher compressive stress than hillocks to grow under the room temperature [5].

The typical cross-sectional image of Sn hillock is presented in Fig. 10, observed on the Sn–1Pb sample surface after 1 year storage. The magnified image in Fig. 10b displays that the Pb grain segregated at the Sn grain boundary blocks the IMC growth, particularly at the root of the hillock. Boettinger et al. [7] proposed that such hillocks form due to the active mobility of more than one grains . The considerably short IMC growth frees Sn grain boundary migration, and allows the grain growth to form the hillock. This hillock formation effectively releases the compressive stress without growing whiskers. It is noteworthy that this mechanism can be observed only 1 wt% lead addition. Our observation proposes another whisker mitigation process without forming equiaxed grain structure.

3.2 Intermetallic compound formation

The formation and growth of IMC formed under pure tin and Sn–1Pb plating after 1 year room temperature storage test are investigated by tin etching as shown in Fig. 11. The results of IMC dispersion also well supported the generation of whisker and hillock formation. In case of pure tin plating (Fig. 11a), the IMC has mainly grown along the Sn grain boundaries, and forms a network structure covering the entire substrate surface. This network disturbs the grain boundary migration that relaxes the residual stress. As explained cross sectional analysis, therefore, the volume expansion from IMCs growth significantly contributes a compressive stress to tin plating layer, and then tin whisker generates to release the accumulated compressive stress. In the case of Sn–1Pb shown in Fig. 11b, the IMC forms more irregularly, and the volume is smaller than the case of pure tin plating. The different IMC growth is already reported by Jhang et al. [13]. They concluded that the lattice diffusion of Cu into Sn grains is enhanced with increasing Pb content in the deposits. However, the mechanism about higher lattice diffusion and hillock growth in the presence of Pb has not been reported [13].

The mobility of grain boundary is increased in Sn–xPb due to the less IMC growth on grain boundary. That is the main reason of hillock formation instead of whisker for releasing the compressive stress under room temperature. It is noteworthy that a small amount addition of just 1 wt% lead in tin changed the formation and growth of IMC during the room temperature storage. The ways of stress relaxation determined by the different IMC network formation are thus related to the growth of whiskers and hillocks.

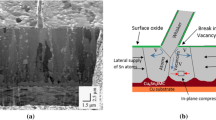

3.3 The formation mechanisms of tin whisker and hillock

The continuous process of accumulating and relieving compress stress during the 1 year storage are different in the pure tin plating and in that with 1 wt% of lead addtion. Fig. 12a illustrates the microstructure change in the pure Sn plating, from the initial as plated to the final state after 1 year. The grains of pure Sn and the IMC have been grown following to grain boundaries after 1 year. The grown IMC disturbs the mobility of Sn grain boundary. Therefore, the compressive stress caused by the volume expansion of IMC and grain growth of Sn can be relieved only by extrusion of Sn whiskers. That is a major cause of whisker generation in pure Sn under room temperature.

On the contrast, as-plated Sn–1Pb and after 1 year of Sn–1Pb are shown in Fig. 12b. The grain growth in Sn–1Pb is the same to that in pure Sn, but the IMCs growth are different. The Pb segregated between Sn grains interrupts the IMCs growth following to Sn grain boundaries. Thin IMC have uniformly formed on the interface. Therefore, the mobility of Sn grain boundary is not interfered during the 1 year. The dotted lines in Fig. 12 (b-2) indicate the grain boundary movement for 1 year. Hillock generation can effectively release the accumulated stress from volume expansion of grain and IMC. The columnar grain structure observed in Sn-1Pb is supposed to generate Sn whiskers in general, though 1 wt% of lead addition into 5 μm plating is enough to mitigate Sn whisker up to 1 year of room temperature storage.

4 Conclusions

Tin whisker mitigation process by lead addition has been investigated by comparing with pure matte Sn and Sn–xPb electro plating with 5 μm thickness on Cu substrate. Tin whiskers have been observed only on pure Sn surface, and no whisker but hillocks on the lead added plating during the 1 year of room temperature storage test. In the tests, whisker growth is efficiently suppressed by only 1 wt% of lead addition without altering the columnar to equiaxed grain structure. The whisker mitigation by such a small amount of lead addition is due to the suppressed IMC growth at the Sn grain boundaries, and freed grain boundary migration. Less obvious pinning of grain boundary migrations results in hillock growth that enough to release the compressive stress in the plating. Our results of higher lead content of 10 wt% agree with the report in the literature [7], though the required amount of lead for whisker mitigation can be less or equal to 1 wt%. The revealed mechanism of whisker mitigation by the least amount of lead addition would indicate the required properties of metal additives that can suppress whiskers like lead. Considering the low solubility of Pb in Sn, we would suggest that Bi can be a replacement candidate of lead for tin whisker mitigation.

References

H.P. Howard, J. Cheng, P.T. Vianco, J.C.M. Li, Acta Mater 59(10), 1957–1963 (2011)

G.T. Galyon, in SMTAI U.S.A (2004), September 26-30, on SMTAI International conference (SMTAI): Chicago

H.L. Cobb, Monthly Rev Amer Electroplaters Soc 33(28), 28–30 (1946)

K.G. Comptom, A. Mendizza, S.M. Arnold, Corrosion 7(10), 327–334 (1951)

B. Horváth, B. Illés, T. Shinohara, G. Harsányi, Thin Solid Films 520(17), 5733–5740 (2012)

K. Suganuma, A. Baated, K.S. Kim, K. Hamasaki, N. Nemoto, T. Nakagawa, T. Yamada, Acta Mater 59, 7255–7267 (2011)

W.J. Boettinger, C.E. Johnson, L.A. Bendersky, K.-W. Moon, M.E. Williams, G.R. Stafford, Acta Mater 53, 5033–5050 (2005)

K.N. Tu, J.C.M. Li, Mater Sci Eng, A 409, 131–139 (2005)

J.W. Osenbach, R.L. Shook, B.T. Vaccaro, B.D. Potteiger, A.N. Amin, K.N. Hooghan et al., IEEE Trans Electron Pack Manuf 28, 36 (2005)

E. Chason, N. Jadhav, F. Pei, JOM 63(10), 62–68 (2011)

N. Jadhav, J. Wasserman, F. Pei, E. Chason, J Electron Mater 41(3), 588–595 (2012)

M. Sobiech, J. Teufel, U. Welzel, E.J. Mittemeijer, W. Hugel, J Electron Mater 40, 2300–2313 (2011)

W. Zhang, F. Schwager, J. Elctrochem, Soc 153(5), C337–C343 (2006)

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) Grant Number 24226017.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jo, JL., Kim, KS., Sugahara, T. et al. Least lead addition to mitigate tin whisker for ambient storage. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 24, 3108–3115 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-013-1218-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-013-1218-y