Abstract 抽象

In dairy herds, mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus is difficult to completely cure on the account that S. aureus can invade bovine mammary epithelial cells (BMECs) and result in persistent infection in the mammary gland. Recent studies have demonstrated that autophagy can participate in cell homeostasis by eliminating intracellular microorganisms. The aim of the study was to investigate why S. aureus can evade autophagy clearance and survive in BMECs. The intracellular infection model was first constructed; then, the bacteria in autophagosome was detected by transmission electron microscopy. The autophagy flux induced by the S. aureus was also evaluated by immunoblot analysis and fluorescent labeling method for autophagy marker protein LC3. In addition, lysosomal alkalization and degradation ability were assessed using confocal microscopy. Results showed that, after infection, a double-layer membrane structure around the S. aureus was observed in BMECs, indicating that autophagy occurred. The change in autophagy marker protein and fluorescent labeling of autophagosome also confirmed autophagy. However, as time prolonged, the autophagy flux was markedly inhibited, leading to obvious autophagosome accumulation. At the same time, the lysosomal alkalization and degradation ability of BMECs were impaired. Collectively, these results indicated that S. aureus could escape autophagic degradation by inhibiting autophagy flux and damaging lysosomal function after invading BMECs.

在奶牛群中, 金黄色葡萄球菌引起的乳腺炎很难完全治愈,因为金黄色葡萄球菌可以侵入牛乳腺上皮细胞 (BMEC) 并导致乳腺持续感染。最近的研究表明,自噬可以通过消除细胞内微生物来参与细胞稳态。该研究的目的是调查为什么金黄色葡萄球菌可以逃避自噬清除并在 BMEC 中存活。首先构建细胞内感染模型;然后,通过透射电镜检测自噬体中的细菌。通过免疫印迹分析和自噬标记蛋白 LC3 荧光标记法评价金黄色葡萄球菌诱导的自噬通量。此外,使用共聚焦显微镜评估溶酶体碱化和降解能力。结果表明,感染后,在 BMECs 中观察到金黄色葡萄球菌周围的双层膜结构,表明发生了自噬。自噬标记蛋白的变化和自噬体的荧光标记也证实了自噬。然而,随着时间的延长,自噬通量受到明显抑制,导致明显的自噬体积累。同时,BMECs 的溶酶体碱化和降解能力受损。综上所述,这些结果表明, 金黄色葡萄球菌在入侵 BMECs 后,可以通过抑制自噬通量和破坏溶酶体功能来逃避自噬降解。

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, bovine mammary epithelial cells, intracellular infection, autophagy, lysosomes

关键词: 金黄色葡萄球菌 ,牛乳腺上皮细胞,细胞内感染,自噬,溶酶体

Introduction 介绍

Mastitis, a type of inflammation that occurs in the mammary parenchyma, can be induced by physical, microbial, and chemical factors, and it is a highly prevalent disease in dairy cows (1). Satisfactory evidence reveals that almost all cases of mastitis are caused by microorganisms (2). Infectious mastitis adversely affects milk quality and quantity and comprises a reservoir of microorganisms that spread the infection to other animals within the herd (3). The most common of such microorganisms is Staphylococcus aureus (4, 5). S. aureus mastitis possesses the characteristics of low cure rate and low pathogen elimination (6, 7). S. aureus can become walled off in the udder cell by thick, fibrous scar tissue so that the antibiotic cannot reach the bacteria. Even microbes that are sensitive to the antibiotics used may be unable to achieve the desired therapeutic effect (7).

乳腺炎是一种发生在乳腺实质中的炎症,可由物理、微生物和化学因素诱发,是奶牛中非常普遍的疾病 ( 1 )。令人满意的证据表明,几乎所有乳腺炎病例都是由微生物引起的( 2 )。传染性乳腺炎会对牛奶质量和数量产生不利影响,并包含将感染传播给牛群内其他动物的微生物库 ( 3 )。此类微生物中最常见的是金黄色葡萄球菌 ( 4 , 5 )。 金黄色葡萄球菌乳腺炎具有治愈率低、病原体消除率低的特点( 6 , 7 )。 金黄色葡萄球菌可以在乳房细胞中被厚厚的纤维疤痕组织围起来,从而使抗生素无法到达细菌。即使是对所用抗生素敏感的微生物也可能无法达到预期的治疗效果 ( 7 )。

Autophagy acts as a “cell guard” to clear intracellular pathogens involved in homeostasis (8–10). Autophagy occurs in the following three steps: formation of autophagosomes, then formation of autolysosomes by fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes, and finally degradation of the cargo within the lysosomes (11). The complete autophagy flux starts from the autophagosomes that form the double-membrane structure. The key step for autophagy to produce biological effects is the formation of autolysosomes by fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes (12). Lysosomes are monolayer-coated vesicles containing diverse acidic hydrolases (13), which can eventually degrade a variety of pathogens in autolysosomes.

自噬充当“细胞守卫”,清除参与体内平衡的细胞内病原体 ( 8 – 10 )。自噬发生在以下三个步骤中:自噬体的形成,然后通过自噬体和溶酶体之间的融合形成自溶酶体,最后降解溶酶体内的货物 ( 11 )。完整的自噬通量始于形成双膜结构的自噬体。自噬产生生物效应的关键步骤是通过自噬体和溶酶体融合形成自溶酶体 ( 12 )。溶酶体是含有多种酸性水解酶 ( 13 ) 的单层包被囊泡,最终可以降解自溶酶体中的多种病原体。

Beclin1 does not only work with Atg14L to regulate the initiation of autophagy (14) but also combine with other proteins and form complexes to regulate the maturation and transport of autophagosomes (15, 16). Following the generation of LC3, the C-terminal fragment of LC3 is immediately cleaved by Atg4, a cysteine protease (17). The cleavage yields its cytosolic form LC3-I and exposes the carboxyl terminal Gly. LC3I is further activated by Atg7 (an E1-like enzyme), transferred to Atg3 (an E2-like enzyme), and finally modified into a membrane-bound form, LC3II (18). LC3II subsequently binds to autophagy vesicles and participates in autophagy activation. After binding with the polyubiquitinated proteins and LC3, SQSTM1/p62 performs the function of a junction protein to send the ubiquitinated protein into autophagy vesicles and degrade in autolysosome (19). Similarly, lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2) is the main protein on the lysosome membrane. LAMP2 not only plays an important role in protecting the integrity of the lysosome membrane but also participates in regulating the fusion of autophagy vesicles and lysosomes (20). Cathepsins D (CTSD) and cathepsin L (CTSL) are essential components of functional lysosomes (21). The acidic environment in lysosomes plays an important role in maturating and activating lysosomal hydrolases and finally in degrading cargo in lysosomes.

Beclin1 不仅与 Atg14L 一起调节自噬的启动 ( 14 ),而且还与其他蛋白质结合并形成复合物来调节自噬体的成熟和转运 ( 15 , 16 )。LC3 生成后,LC3 的 C 端片段立即被半胱氨酸蛋白酶 Atg4 裂解 ( 17 )。裂解产生其胞质形式 LC3-I 并暴露羧基末端 Gly。LC3I 被 Atg7(一种 E1 样酶)进一步激活,转移到 Atg3(一种 E2 样酶),最后修饰成膜结合形式 LC3II ( 18 )。LC3II 随后与自噬囊泡结合并参与自噬激活。与多泛素化蛋白和 LC3 结合后,SQSTM1 / p62 执行连接蛋白的功能,将泛素化蛋白送入自噬囊泡并在自溶酶体中降解( 19 )。同样,溶酶体相关膜蛋白 2 (LAMP2) 是溶酶体膜上的主要蛋白质。LAMP2 不仅在保护溶酶体膜的完整性方面发挥重要作用,而且还参与调节自噬囊泡和溶酶体的融合( 20 )。组织蛋白酶 D (CTSD) 和组织蛋白酶 L (CTSL) 是功能性溶酶体的重要组成部分 ( 21 )。溶酶体中的酸性环境在溶酶体水解酶的成熟和激活以及最终降解溶酶体中的货物方面起着重要作用。

Recent studies have reported that after S. aureus infection, autophagosomes are formed, but the autophagosomes and lysosomes cannot fuse normally to form autolysosomes, thus avoiding autophagy degradation (10, 22). The resistance of bovine mammary epithelial cells (BMECs) to S. aureus infection and induction of autophagy has not been thoroughly explored. Therefore, in this study, the characteristics of autophagy induced by S. aureus-infected BMECs was systematically described by detecting autophagic flux-related indicators and assessing lysosomal functions.

最近的研究报道, 金黄色葡萄球菌感染后,会形成自噬体,但自噬体和溶酶体不能正常融合形成自溶酶体,从而避免了自噬降解( 10 , 22 )。牛乳腺上皮细胞 (BMEC) 对金黄色葡萄球菌感染和诱导自噬的耐药性尚未得到彻底探索。因此,本研究通过检测自噬通量相关指标和评估溶酶体功能,系统描述了金黄色葡萄球菌感染的 BMECs 诱导的自噬特征。

Materials and Methods 材料与方法

Reagents and Antibodies 试剂和抗体

4’,6-Diamidine-2’-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) and acridine orange (A8120) were purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific Pierce (Rockford, IL, United States). LysoTracker Deep Red and Enhanced Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, C0042) were from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (L3000015) was purchased from Invitrogen (Rockford, IL, United States). Plasmid extraction kit was from TIANGEN Biotech (Beijing, China). Lysostaphin was from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Glutaraldehyde, formaldehyde, osmium tetroxide, and epoxy (low viscosity) resin were from Merck Millipore Company (Billerica, CA, United States).

4',6-二脒-2'-苯基吲哚二盐酸盐(DAPI)和吖啶橙(A8120)购自 Solarbio(中国北京)。二辛可宁酸(BCA)蛋白检测试剂盒和增强化学发光(ECL)试剂盒购自 Thermo Fisher Scientific Pierce(美国伊利诺伊州罗克福德)。LysoTracker Deep Red 和增强型细胞计数试剂盒-8(CCK-8,C0042)来自 Beyotime Biotechnology(中国上海)。Lipofectamine 2000 转染试剂(L3000015)购自 Invitrogen(美国伊利诺伊州罗克福德)。质粒提取试剂盒来自天根生物技术(中国北京)。溶菌素来自三宫生物技术(中国上海)。戊二醛、甲醛、四氧化锇和环氧树脂(低粘度)树脂来自默克 Millipore 公司(美国加利福尼亚州比勒里卡)。

The following primary antibodies were used: anti-p62/SQSTM1, anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and anti-CTSL/major excreted protein (MEP) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, United States); anti-LC3B, anti-LAMP2, and anti-β-actin were obtained from Beyotime (Shanghai, China); anti-α-tubulin, anti-Beclin1, and anti-CTSD were from Proteintech (Chicago, IL, United States); Peroxidase-Conjugated AffiniPure Goat Antimouse IgG (ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China); and goat antirabbit IgG (CWBIO, Beijing, China).

使用以下一抗:抗 p62/SQSTM1、抗甘油醛 3-磷酸脱氢酶(GAPDH)和抗 CTSL/主要排泄蛋白(MEP)购自 Abcam(美国马萨诸塞州剑桥);抗 LC3B、抗 LAMP2、抗β-肌动蛋白来源于 Beyotime(中国上海);抗α微管蛋白、抗 Beclin1 和抗 CTSD 来自 Proteintech(美国伊利诺伊州芝加哥);过氧化物酶偶联的 AffiniPure 山羊抗小鼠 IgG(ZSGB-BIO,中国北京);和山羊抗兔 IgG(CWBIO,北京,中国)。

Bacterial Strains and Cell Culture

细菌菌株和细胞培养

Staphylococcus aureus strains (ATCC 25923) were cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C for 12 h. After reaching OD600 = 0.8–1.2, the bacteria were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) thrice to treat the cells. The bovine mammary epithelial cell line (MAC-T) was digested with trypsin at 37°C for 5 min and centrifuged at 1,000–2,000 r/min for 5 min. The MAC-T cells were then maintained overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 without antibiotics in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum until the cell density reached 80%.

金黄色葡萄球菌菌株(ATCC 25923)在 37°C 的 Luria-Bertani(LB)肉汤中培养 12 h。达到 OD600 = 0.8–1.2 后,用磷酸盐缓冲盐水(PBS)洗涤细菌三次以处理细胞。牛乳腺上皮细胞系(MAC-T)在 37°C 下用胰蛋白酶消化 5 分钟,并以 1,000–2,000 r / min 离心 5 分钟。然后在 Dulbecco 改良的 Eagle 培养基(DMEM)中,在 5%CO2 中将 MAC-T 细胞维持在 37°C 下过夜,不含抗生素,并补充 10%(v / v)热灭活胎牛血清,直到细胞密度达到 80%。

Cell Viability Assay 细胞活力测定

MAC-T cells were seeded into 96-well plates (1 × 104 cells/well) in 100 μl of DMEM medium. Twenty-four hours later, cells were infected with S. aureus [multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 8] for 2, 4, 6, and 8 h to assess the damage of the cells. The cell viability assay was performed using CCK-8 following the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance was read at 450 nm by the microplate reader (Sunrise, Salzburg, Austria).

将 MAC-T 细胞接种到 100 μl DMEM 培养基中的 96 孔板(1 × 10 个 4 个细胞/孔)中。24 小时后,用金黄色葡萄球菌感染细胞[感染多重性(MOI)= 8]2、4、6 和 8 小时,以评估细胞的损伤。按照制造商的说明使用 CCK-8 进行细胞活力测定。吸光度由酶标仪在 450 nm 处读取(Sunrise,Salzburg,Austria)。

Immunofluorescence Staining

免疫荧光染色

Cells were seeded on sterile coverslips placed in 24-well plates. The cells were then infected with S. aureus for 2 h, and they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 8 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, and blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Slides were first stained with anti-α-tubulin antibody (1:200 diluted in PBS) for 2 h at RT. Cells were washed by PBS thrice and then incubated with peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure (1:100 diluted in PBS) secondary antibody for 1 h and washed with PBS again. The nuclei were stained with 100 μl DAPI (blue) and washed thrice with PBS. Finally, all slides were mounted with ProLong Gold antifade mountant. Images were conducted on the Leica TCS SPE confocal microscope with a × 63 (1.3 numerical aperture) oil immersion objective. Images were taken at laser wavelengths of 555 and 488 nm. Images for colocalization analysis (percentage of protein–protein colocalization) were assessed using the JaCoP plugin in ImageJ after thresholding of individual frames. All colocalization calculations were performed on three independent experiments with 20 cells per condition in each experiment.

将细胞接种在放置在 24 孔板中的无菌盖玻片上。然后用金黄色葡萄球菌感染细胞 2 h,用 4%多聚甲醛固定 8 min,用 0.2% Triton X-100 在 PBS 中透化 5 min,在室温(RT)下用 5%脱脂牛奶封闭 1 h。首先用抗α微管蛋白抗体(1:200 在 PBS 中稀释)在室温下对载玻片染色 2 小时。用 PBS 洗涤细胞三次,然后与过氧化物酶偶联的 AffiniPure(1:100 在 PBS 中稀释)二抗孵育 1 小时,然后再次用 PBS 洗涤。用 100 μl DAPI(蓝色)染色细胞核,并用 PBS 洗涤 3 次。最后,所有载玻片都安装了 ProLong Gold 抗淬灭封片剂。图像是在徕卡 TCS SPE 共聚焦显微镜上进行的,该显微镜具有 × 63(1.3 数值孔径)油浸物镜。图像是在 555 和 488 nm 的激光波长下拍摄的。在对单个帧进行阈值设置后,使用 ImageJ 中的 JaCoP 插件评估用于共定位分析的图像(蛋白质-蛋白质共定位的百分比)。所有共定位计算均在三个独立实验中进行,每个实验中每个条件有 20 个细胞。

Transfection 转染

Ad-GFP-LC3B and Ad-mCherry-GFP-LC3B were obtained from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). MAC-T cells were prepared using Lipofectamine 2000 with 4 μg of DNA per well on a six-well plate transfected with Ad-GFP-LC3B and Ad-mCherry-GFP-LC3B when the cell density reached roughly 70% confluence. After transfected for 36 h, the cells were infected with S. aureus and observed with the confocal microscope (TCS SPE, Leica, Germany). Representative cells were selected and photographed. Twenty cells per condition from three independent experiments were applied for statistical analysis.

Ad-GFP-LC3B 和 Ad-mCherry-GFP-LC3B 来自 Beyotime(中国上海)。当细胞密度达到大约 70% 汇合时,使用 Lipofectamine 2000 制备 MAC-T 细胞,每孔 4 μg DNA 转染了 Ad-GFP-LC3B 和 Ad-mCherry-GFP-LC3B 的六孔板上。转染 36 小时后,用金黄色葡萄球菌感染细胞,并用共聚焦显微镜(TCS SPE,徕卡,德国)观察。选择并拍摄代表性细胞。每个条件对来自三个独立实验的 20 个细胞进行统计分析。

Western Blotting 蛋白质印迹

After infected with S. aureus for 2, 4, 6, and 8 h, MAC-T cells were collected and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer solution on ice for 30 min. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min, the concentration of the protein samples was measured by BCA assay kit. Through sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes using a semidry blotting system. The blots were blocked in Tris–buffered saline (TBS) containing 5% skimmed milk powder. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies. Washed three times with Tris–buffered saline buffer with Tween 20 (TBST), membranes were then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at RT. The signals were detected using ECL-Plus Western blot detection system.

金黄色葡萄球菌感染 2、4、6、8 h 后,收集 MAC-T 细胞,在冰上的放射免疫沉淀测定(RIPA)缓冲溶液中裂解 30 min。在 12,000 × g 离心 15 min 后,用 BCA 检测试剂盒测量蛋白质样品的浓度。通过十二烷基硫酸钠(SDS)-聚丙烯酰胺凝胶电泳,使用半干印迹系统将蛋白质转移到聚偏二氟乙烯(PVDF)膜上。印迹在含有 5%脱脂奶粉的 Tris 缓冲盐水(TBS)中封闭。将膜与一抗在 4°C 下孵育过夜。用 Tris 缓冲盐水缓冲液和吐温 20 (TBST) 洗涤 3 次,然后将膜与二抗在室温下孵育 1 小时。使用 ECL-Plus 蛋白质印迹检测系统检测信号。

Acridine Orange and LysoTracker Deep Red Staining

吖啶橙和 LysoTracker 深红色染色

Cells grown on coverslips were incubated with 5 μg/ml acridine orange or 100 nM LysoTracker Deep Red at 37°C for 30 min after infected with S. aureus for 2, 4, 6, and 8 h. The fluorescence signal of acridine orange and LysoTracker Deep Red was subsequently observed under a confocal microscope.

在用金黄色葡萄球菌感染 2、4、6 和 8 小时后,将盖玻片上生长的细胞与 5 μg/ml 吖啶橙或 100 nM LysoTracker 深红在 37°C 下孵育 30 分钟。随后在共聚焦显微镜下观察吖啶橙和 LysoTracker Deep Red 的荧光信号。

Transmission Electron Microscopy

透射电子显微镜

After fixing with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 5% formaldehyde for at least 2 h, the samples were washed thrice with 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution. The samples were fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 h. The above operations were all performed at 4°C. Following, dehydration was performed in stages in 50, 70, 80, 90, and 100% acetone for 15 min. The embedding solution and propylene oxide were 1:1 at normal temperature for 1 h, and the embedding solution and propylene oxide were 3:1 at normal temperature for 5 h. The embedding solution was saturated on a shaker for 5 h at normal temperature. Finally, it was left to stand at 37°C for 12 h and transferred to 45°C for 24 h, then to 60°C for 24 h for curing. Ultrathin sections were then prepared and stained. Samples were examined in a Zeiss TEM 910 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV and at calibrated magnifications. Images were recorded digitally at calibrated magnifications with a slow-scan charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (ProScan, 1,024 × 1,024, Scheuring, Germany) with ITEM Software (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions, Münster, Germany).

用 2.5%戊二醛和 5%甲醛固定至少 2 h 后,用 0.1 M 磷酸盐缓冲溶液洗涤样品 3 次。用 1%四氧化锇固定样品 2 h。上述作均在 4°C 下进行。 随后,在 50、70、80、90 和 100%丙酮中分阶段脱水 15 分钟。包埋液与环氧丙烷在常温下 1:1,包埋液与环氧丙烷在常温下 5 h 为 3:1。将包埋溶液在常温下在振荡器上饱和 5 h。最后,将其在 37°C 下静置 12 h,然后转移到 45°C 下 24 h,然后转移到 60°C 下 24 h 进行固化。然后制备超薄切片并染色。在蔡司 TEM 910(蔡司,Oberkochen,德国)中以 80 kV 的加速电压和校准的放大倍率检查样品。使用慢速扫描电荷耦合器件 (CCD) 相机(ProScan,1,024 × 1,024,Scheuring,德国)和 ITEM 软件(Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions,Münster,Germany)以校准放大倍数以数字方式记录图像。

Results 结果

Cell Infection Model Successfully Constructed

细胞感染模型构建成功

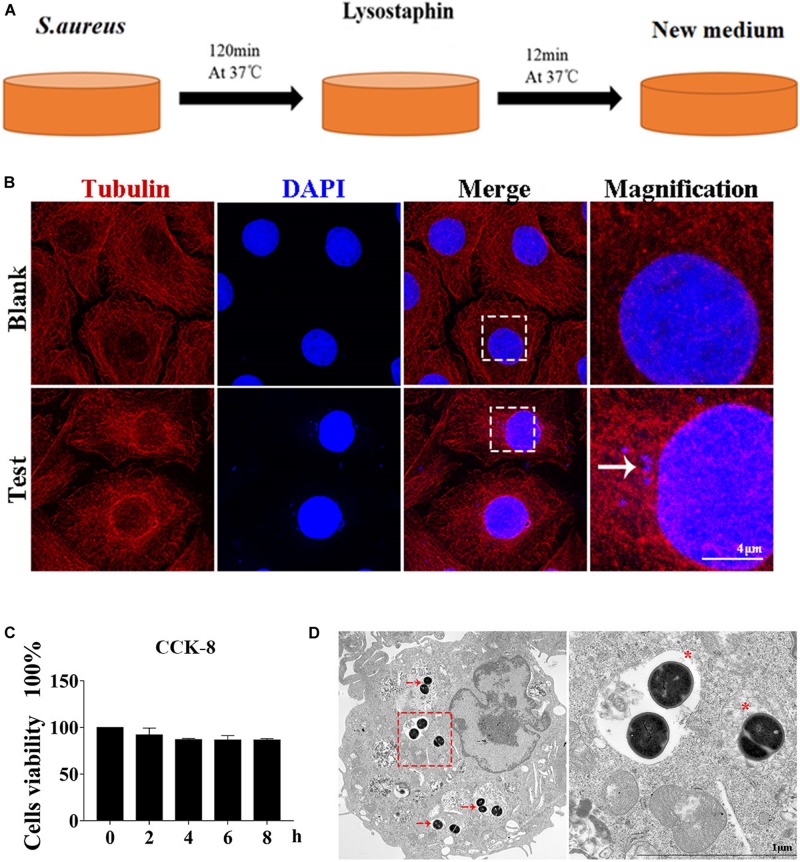

Autophagy caused by intracellular S. aureus in MAC-T was explored. Methods in a previous study (10) were slightly modified to establish an intracellular infection model. Incubation at 37°C for 2 h can effectively enable S. aureus invasion of MAC-T cells, and lysostaphin (100 μg/ml) can effectively kill the extracellular S. aureus. The cell infection model was successfully constructed after 12 min of lysostaphin treatment (Figure 1A).

探讨了 MAC-T 中细胞内金黄色葡萄球菌引起的自噬作用。对先前研究( 10 )中的方法进行了轻微修改,以建立细胞内感染模型。在 37°C 下孵育 2 h 可有效使金黄色葡萄球菌侵袭 MAC-T 细胞,溶菌素(100 μg/ml)可有效杀死细胞外金黄色葡萄球菌。溶菌素处理 12 min 后成功构建细胞感染模型( Figure 1A )。

FIGURE 1. 图 1.

Cell infection model successfully constructed. (A) Schematic of experimental design. Eukaryotic cells and S. aureus were incubated at 37°C for 120 min. Lysostaphin was then added to kill all bacteria outside the cell. After incubation at 37°C for 12 min, the culture medium was changed. (B) Representative confocal images showing colocalization of tubulin with 4’,6-diamidine-2’-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI). High magnification images of the outlined area are shown on the right. “→” points to S. aureus. Scale bars: 4 μm. (C) Effect of S. aureus invasion time on cell activity in MAC-T cells. Values were shown as means ± SD, n = 3. (D) MAC-T cells were infected with S. aureus, fixed 2 hpi, and analyzed by transmission electron microscopy. “→” points to S. aureus. “*” is a double-layer membrane. Scale bars: 200 nm.

细胞感染模型构建成功。(A) 实验设计示意图。将真核细胞和金黄色葡萄球菌在 37°C 下孵育 120 分钟。然后添加溶菌菌素以杀死细胞外的所有细菌。在 37°C 下孵育 12 分钟后,更换培养基。(B) 显示微管蛋白与 4',6-二脒-2'-苯基吲哚二盐酸盐 (DAPI) 共定位的代表性共聚焦图像。轮廓区域的高放大图像显示在右侧。“→”指向金黄色葡萄球菌 。比例尺:4 μm。(C) 金黄色葡萄球菌侵袭时间对 MAC-T 细胞活性的影响。值显示为均值 ± SD,n = 3。(D)MAC-T 细胞感染金黄色葡萄球菌,固定 2 hpi,透射电镜分析。“→”指向金黄色葡萄球菌 。“*”是双层膜。比例尺:200 nm。

As shown in Figure 1B, S. aureus was observed in the MAC-T of the test group but not in the blank control group. In addition, CCK-8 assay indicated that continuous infection with S. aureus for 8 h did not affect cell activity (Figure 1C). Through transmission electron microscope analysis, the S. aureus bacteria in MAC-T were presented along with the autophagic vesicle membrane structure around the bacteria (Figure 1D).

如图所示 Figure 1B ,在试验组的 MAC-T 中观察到金黄色葡萄球菌,但在空白对照组中未观察到金黄色葡萄球菌。此外,CCK-8 测定表明, 连续感染金黄色葡萄球菌 8 小时不会影响细胞活性 ( Figure 1C )。通过透射电镜分析,呈现了 MAC-T 中的金黄色葡萄球菌以及细菌周围的自噬囊泡膜结构( Figure 1D )。

Intracellular S. aureus Induced Autophagy

细胞内金黄色葡萄球菌诱导的自噬

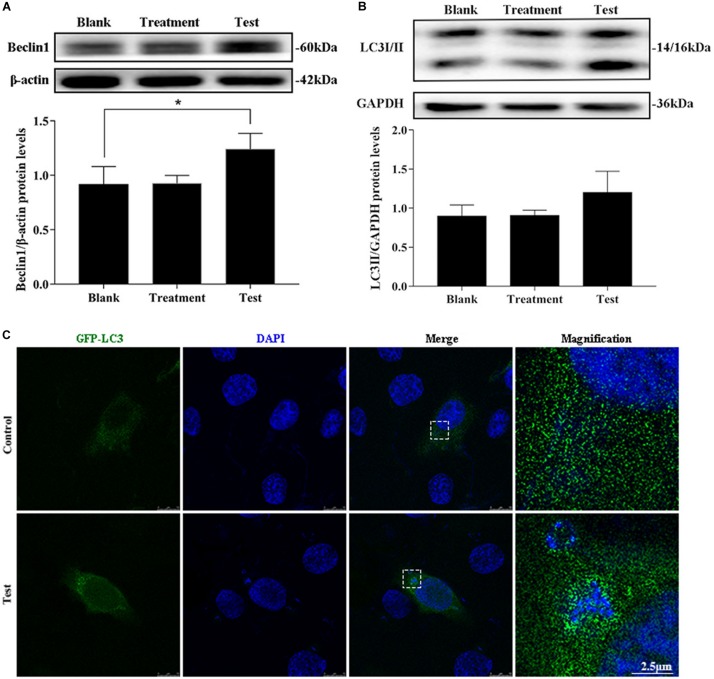

The treatment group was the cells treated with lysostaphin alone, and autophagy did not occur in these cells. However, infection with S. aureus resulted in a substantial increase in Beclin1 expression (Figures 2A,B). The conversion of 1 light chain 3I LC3I to LC3II also increased (p = 0.637). Intuitively, the green fluorescent spots of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-LC3 clustered around the intracellular bacteria in the test group, whereas the blank group showed a diffuse distribution (Figure 2C). This outcome suggested that S. aureus induce autophagy in MAC-T.

治疗组为单独溶菌素处理的细胞,这些细胞未发生自噬。然而, 金黄色葡萄球菌感染导致 Beclin1 表达大幅增加 ( Figures 2A,B )。1 个轻链 3I LC3I 向 LC3II 的转化率也有所增加 (p = 0.637)。直观地,绿色荧光蛋白(GFP)-LC3 的绿色荧光斑点聚集在测试组的细胞内细菌周围,而空白组则呈现弥漫性分布( Figure 2C )。这一结果表明金黄色葡萄球菌诱导 MAC-T 中的自噬。

FIGURE 2. 图 2.

Intracellular S. aureus induced the occurrence of autophagy. (A) Protein level of Beclin1 in MAC-T cells with different treatments. (B) Protein level of light chain 3II (LC3II) in MAC-T cells with different treatments. Upper panels: representative Western blot images; lower panels: quantitative analysis (mean ± SEM, n = 3, *p < 0.05). (C) Formation of GFP-LC3 puncta was observed under the confocal microscope. Scale bars: 2.5 μm.

细胞内金黄色葡萄球菌诱导自噬的发生。(A) 不同处理的 MAC-T 细胞中 Beclin1 的蛋白水平。(B) 不同处理的 MAC-T 细胞轻链 3II(LC3II)蛋白水平。上图:代表性蛋白质印迹图像;下图:定量分析(SEM ±平均值,n = 3,*p < 0.05)。(C) 在共聚焦显微镜下观察到 GFP-LC3 点的形成。比例尺:2.5 μm。

Autophagy Flux Was Blocked

自噬通量被阻断

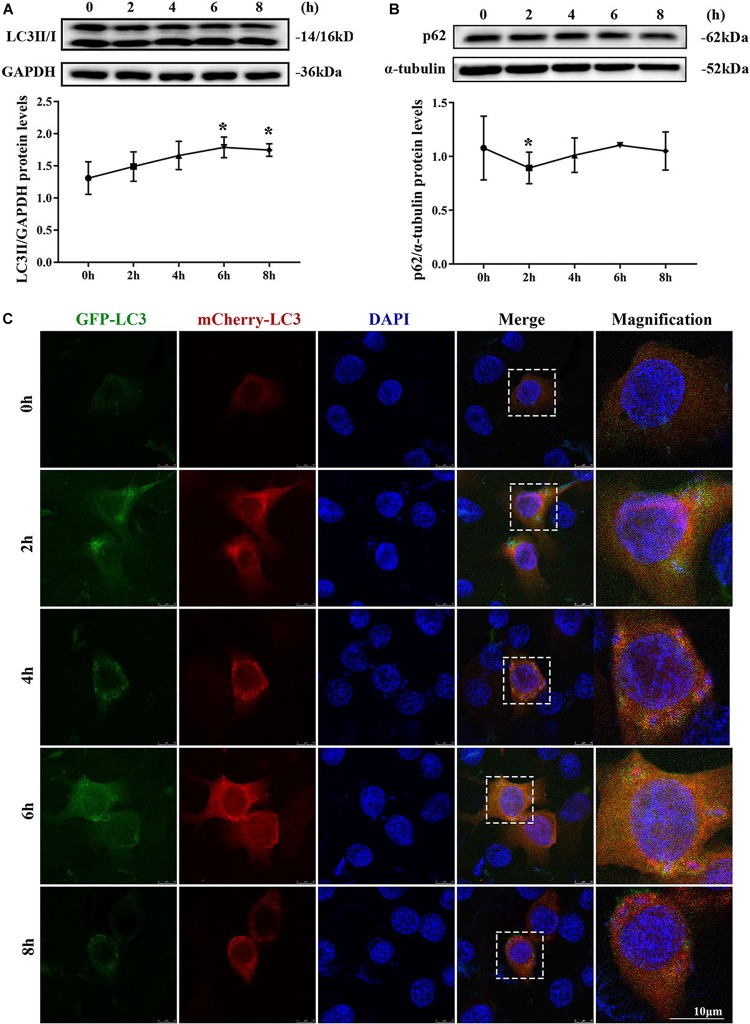

MAC-T cells were continuously infected for 8 h to observe the occurrence of dynamic autophagy. The ratio of LC3II/GAPDH showed an increasing trend by Western blotting, and the protein expression level of SQSTM1/p62 presented a similar trend after 4 h of infection (Figures 3A,B). The results of the cells transfected with mCherry-GFP-LC3 indicated that yellow mottled fluorescence tended to increase within 6 h as the infection time extended, whereas red mottled fluorescence became excessed and peaked at the eighth hour (Figure 3C). This observation suggested that autophagy flux was blocked during S. aureus infection.

连续感染 MAC-T 细胞 8 h,观察动态自噬的发生情况。Western blotting 对 LC3II/GAPDH 的比值呈上升趋势,感染 4 h 后 SQSTM1/p62 蛋白表达水平呈类似趋势( Figures 3A,B )。转染 mCherry-GFP-LC3 的细胞结果表明,随着感染时间的延长,黄色斑驳荧光在 6 h 内趋于增加,而红色斑驳荧光变得过多并在第 8 小时达到峰值( Figure 3C )。这一观察结果表明, 在金黄色葡萄球菌感染期间,自噬通量被阻断。

FIGURE 3. 图 3.

Autophagy flux was blocked. (A) Light chain 3II (LC3II) protein level in MAC-T cells. (B) SQSTM1/p62 protein level in MAC-T cells. Upper panels: representative Western blot images; lower panels: quantitative analysis (mean ± SEM, n = 3, *p < 0.05). Cells grown on coverslips were transfected with mCherry-GFP-LC3 for 36 h, then infected with S. aureus at different times to monitor the autophagic flux. Representative confocal images were presented in (C). Scale bars: 10 μm.

自噬通量被阻断。(A)MAC-T 细胞中轻链 3II(LC3II)蛋白水平。(B)MAC-T 细胞中 SQSTM1/p62 蛋白水平。上图:代表性蛋白质印迹图像;下图:定量分析(SEM±平均值,n = 3,*p < 0.05)。用 mCherry-GFP-LC3 转染在盖玻片上生长的细胞 36 h,然后在不同时间用金黄色葡萄球菌感染以监测自噬通量。(C) 中介绍了具有代表性的共聚焦图像。比例尺:10 μm。

S. aureus Causes Increased pH in Lysosomes

金黄色葡萄球菌导致溶酶体 pH 值升高

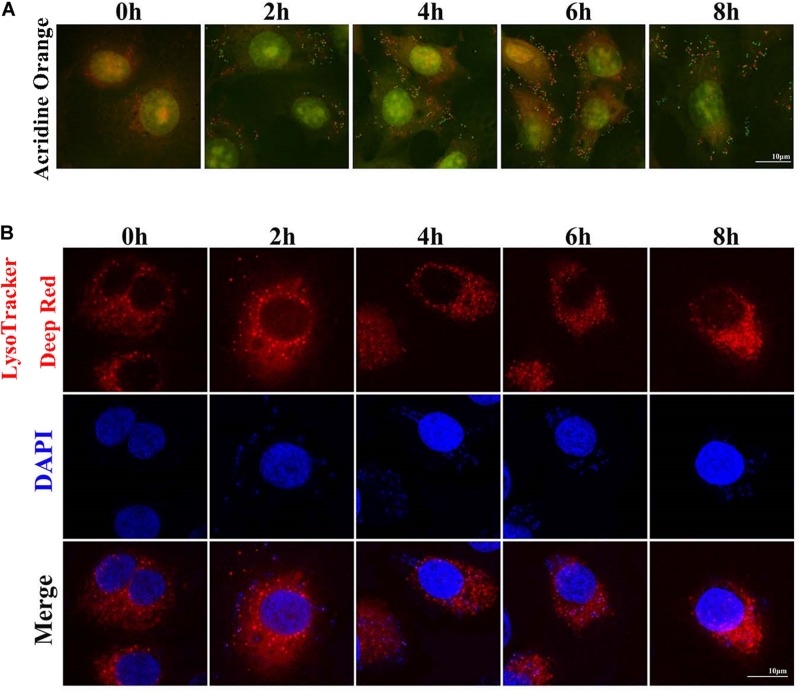

Two sensitive lysosome pH probes were used to monitor lysosome pH changes in MAC-T (Figure 4). First, acridine orange staining showed that cytoplasm presented diffuse fluorescence with green color. Lysosomes showed red fluorescence, and intracellular live bacteria reflected green mottled fluorescence. The intracellular red fluorescence was enhanced during the second to sixth hour postinfection. LysoTracker Deep Red displayed red fluorescence in lysosomes in a pH-dependent manner, and fluorescence enhancement indicates a decrease in lysosome pH. Similarly, red fluorescence around intracellular S. aureus was reduced at the fourth and sixth hour postinfection. These results indicated that infection with S. aureus increased the pH in lysosomes.

使用两个灵敏的溶酶体 pH 探针监测 MAC-T 中溶酶体 pH 变化 Figure 4 ( )。首先,吖啶橙染色显示细胞质呈现绿色弥漫荧光。溶酶体显示红色荧光,细胞内活细菌反射绿色斑驳荧光。感染后第 2 至 6 小时内细胞内红色荧光增强。LysoTracker Deep Red 以 pH 依赖性方式在溶酶体中显示红色荧光,荧光增强表明溶酶体 pH 值降低。同样,细胞内金黄色葡萄球菌周围的红色荧光在感染后第 4 小时和第 6 小时减少。这些结果表明, 金黄色葡萄球菌感染会增加溶酶体的 pH 值。

FIGURE 4. 图 4.

Staphylococcus aureus causes increased pH in lysosomes. (A) Cells stained with 100 nM LysoTracker Deep Red at 37°C for 30 min after S. aureus infection to assess the lysosomal pH. (B) Cells stained with 10 μg/ml acridine orange at 37°C for 30 min. Slides were viewed using a scanning confocal microscope, and representative confocal images were shown. Scale bars: 10 μm.

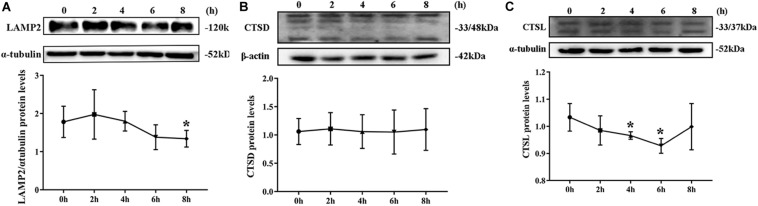

Degradation of Lysosomes Was Impaired

By Western blotting, LAMP2 protein level substantially decreased from the second hour postinfection (Figure 5A). By contrast, no remarkable change was noted in CTSD protein level during S. aureus infection (Figure 5B). The expression of CTDL protein also decreased in the beginning of infection but recovered at the eighth hour (Figure 5C). These outcomes confirmed that lysosomal degradation was impaired after S. aureus infection of MAC-T.

FIGURE 5.

Degradation of lysosomes was impaired. (A) Protein level of lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2) in MAC-T cells treated at different times. (B) Cathepsin D (CTSD) expression level in MAC-T cells treated at different times. (C) Cathepsin L (CTSL) expression level in MAC-T cells treated at different times. Upper panels: representative Western blot images; lower panels: quantitative analysis (mean ± SEM, n = 3, *p < 0.05).

Discussion

Staphylococcus aureus mastitis is caused mainly by the pathogens entering the lobules through the milk ducts (23). First, S. aureus adheres to the mammary epithelial cells by adhesion molecules, then settles down and multiplies (24). S. aureus can invade cells to evade the body’s immune defense and survive in the cells (25). As the “cell guard,” autophagy plays a role in removing foreign pathogens (9). Moreover, the integrity of autophagy affects the cells’ defense against pathogens. Therefore, exploring the interaction between S. aureus and autophagy flux in BMECs is important.

Autophagosome formation is the first step of autophagy flux. In an attempt to visualize S. aureus inside the classical vesicle of autophagosome compartments, transmission electron microscopy was used. S. aureus cells residing within a double membrane structure were not identified, but other types of S. aureus containing vesicles were observed as well as S. aureus residing freely in the cytoplasm (Figure 1D). S. aureus were undergoing replication in cell centrally placed inside a multivesicular body and enclosed inside a single membrane compartment. Another type of intracellular compartment containing S. aureus was observed. A spacious vesicle not only held a bacterial cell but also contained cytoplasmic (membranous) material that might have resulted from intraluminal vesicle formation or from fusion with autophagic vesicles. The structure originated from phagocytosis and not from xenophagy. Finally, replicating S. aureus cells were spotted inside vesicles as well as within the cytoplasm. These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies on Salmonella typhimurium (26). These results identified the occurrence of cellular autophagy and bacterial escape.

Beclin1, which functions as a molecular scaffold that binds with other Atg regulatory proteins, regulates autophagy levels and locates autophagosomes (27). Beclin1 expression enhancement can be used as an important index to evaluate the increase in autophagy level. The results showed that the expression of Beclin1 protein substantially increased after infection with S. aureus. LC3 is the most widely used molecular marker of autophagosome in current studies because it can specifically locate the autophagosome membrane. Furthermore, this study found that the amount of LC3II was related to the intensity of autophagy (28). GFP-LC3 transfected cells are a common tool for autophagy evaluation. In this study, LC3II expression level increased after S. aureus invaded MAC-T cells. These results suggested that S. aureus could induce autophagy in BMECs.

The fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes is critical in autophagic flux. SQSTM1/p62 is the most critical “truck protein” for selective autophagy, and they are also known as selective autophagy receptors (29). SQSTM1/p62 acts as a linker protein to mediate the degradation of its recognition substrate (30). The enhanced SQSTM1/p62 protein level is considered a symbol that the autophagy flux is blocked (28). A previous study showed that the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes was hindered by S. aureus and that the formation of autophagosomes was conducive to the intracellular survival of bacteria (31). The results of the present study revealed that the protein expression level of SQSTM1/p62 began to rise from the second hour during continuous infection of S. aureus in MAC-T. The mCherry-GFP-LC3 is an adenovirus specifically designed to detect the levels of autophagic flux (32). The present study observed that mCherry-GFP-LC3 showed yellow fluorescence accumulation after bacterial infection. From the above results, S. aureus infection blocks the autophagy flux in BMECs by interfering with the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes.

Lysosomal degradation also affects autophagy flux. Under normal physiological conditions, lysosomes are weakly acidic. Considering the acidic environment of lysosomes, a large number of proteolytic enzymes can play a role in degradation (33). LysoTracker Deep Red is a fluorescent probe that can accumulate in acidic vesicles. The intensity and quantity of red fluorescence represent the pH and quantity of lysosomes (34, 35). In the current study, the red fluorescence weakened, and the number of spots decreased at the fourth and sixth hour of S. aureus infection. Acridine orange can stain the double-stranded DNA green and single-stranded RNA red. In live cells, acridine orange can be accumulated by acidic vesicles that yield prominent red signals (35). Our results showed that the red fluorescence decreased sharply at the eighth hour after S. aureus infection, suggesting that once S. aureus infected MAC-T cells, the pH in lysosome increased. LAMP2 is the main protein on the lysosome membrane. LAMP2 not only plays an important role in protecting the integrity of the lysosome membrane but also participates in regulating the fusion of autophagy vesicles and lysosomes. When autolysosome pathway was activated, the LAMP2 expression level increased and located on the perinuclear lysosome (20). In this study, Western blot results showed that the LAMP2 protein expression level decreased gradually after S. aureus infection. CTSD is an aspartic acid-like lysosomal peptide endonuclease whose normal function is to hydrolyze hormones, peptide precursors, peptides, and structural and functional proteins in the acidic environment of lysosomes (36, 37). CTSL is the main member of the lysosomal cysteine protease family. CTSL can hydrolyze proteins, plasma proteins, hormones, and phagocytic bacteria by activating CTSB (38). The present study found that S. aureus infection of MAC-T did not affect the expression of CTSD but inhibited that of CTSL. This finding indicated that the invasion of S. aureus led to impaired degradation of lysosomes.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

YL: conceptualization. NG: data curation, investigation, and writing—original draft. XW and XY: formal analysis. NG and RW: methodology. JL and YL: project administration, writing, reviewing, and editing. YZ: software. JL: supervision. YL and MZ: validation. XW: visualization.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31802259 and 31872535), Shandong Natural Science Foundation of China (ZR2018MC027 and ZR2016CQ29), and Funds of Shandong “Double Tops” Program.

References

- 1.Hu X, Li S, Fu Y, Zhang N. Targeting gut microbiota as a possible therapy for mastitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol. (2019) 38:1409–23. 10.1007/s10096-019-03549-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kampa J, Sukolapong V, Chaiyotwittakun A, Rerkusuke S, Polpakdee A. Chronic mastitis in small dairy cattle herds in Muang Khon Kaen. Thai Vet Med. (2010) 40:265–72. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali T, Rahman A, Qureshi MS, Hussain MT, Khan MS, Uddin S, et al. Effect of management practices and animal age on incidence of mastitis in Nili Ravi buffaloes. Trop Anim Health Prod. (2014) 46:1279–85. 10.1007/s11250-014-0641-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sol J, Sampimon OC, Barkema HW, Schukken YH. Factors associated with cure after therapy of clinical mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. J Dairy Sci. (2000) 83:278–84. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)74875-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwiatek M, Parasion S, Mizak L, Gryko R, Bartoszcze M, Kocik J. Characterization of a bacteriophage, isolated from a cow with mastitis, that is lytic against Staphylococcus aureus strains. Arch Virol. (2012) 157:225–34. 10.1007/s00705-011-1160-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du PJ. Bovine mastitis therapy and why it fails. J S Afr Vet Assoc. (2012) 71:201–8. 10.4102/jsava.v71i3.714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linder M, Paduch JH, Grieger AS, Mansion-De VE, Knorr N, Zinke C, et al. [Cure rates of chronic subclinical Staphylococcus aureus mastitis in lactating dairy cows after antibiotic therapy]. Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr. (2013) 126:291–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cullinane M, Gong L, Li X, Lazar-Adler N, Tra T, Wolvetang E, et al. Stimulation of autophagy suppresses the intracellular survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei in mammalian cell lines. Autophagy. (2008) 4:744–53. 10.4161/auto.6246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Z, Fux B, Goodwin M, Dunay IR, Strong D, Miller BC, et al. Autophagosome-independent essential function for the autophagy protein Atg5 in cellular immunity to intracellular pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. (2008) 4:458–69. 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumann Y, Bruns SA, Rohde M, Prajsnar TK, Foster SJ, Schmitz I. Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus eludes selective autophagy by activating a host cell kinase. Autophagy. (2016) 12:2069–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto M, Suzuki SO, Himeno M. The effects of dynein inhibition on the autophagic pathway in glioma cells. Neuropathology. (2010) 30:1–6. 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2009.01034.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganley IG. Autophagosome maturation and lysosomal fusion. Essays Biochem. (2013) 55:65–78. 10.1042/bse0550065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuda M. Biogenesis of the lysosomal membrane. Sub Cell Biochem. (1994) 22:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benyu M, Weipeng C, Wenxia L, Chan G, Zhen Q, Yan Z, et al. Dapper1 promotes autophagy by enhancing the Beclin1-Vps34-Atg14L complex formation. Cell Res. (2014) 24:912–24. 10.1038/cr.2014.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itakura E, Mizushima N. Atg14 and UVRAG: mutually exclusive subunits of mammalian Beclin 1-PI3K complexes. Autophagy. (2009) 5:534–6. 10.4161/auto.5.4.8062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsunaga K, Saitoh T, Tabata K, Omori H, Satoh T, Kurotori N, et al. Two Beclin 1-binding proteins, Atg14L and Rubicon, reciprocally regulate autophagy at different stages. Nat Cell Biol. (2009) 11:385–96. 10.1038/ncb1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, Li J, Ouyang L, Liu B, Cheng Y. Unraveling the roles of Atg4 proteases from autophagy modulation to targeted cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. (2016) 373:19–26. 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiaxue W, Yongjun D, Wei S, Chao L, Haijie M, Yuxi S, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of rat LC3A and LC3B–two novel markers of autophagosome. Biochem Biophy Res Commun. (2016) 339:437–42. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. Aip Adv. (2007) 282:24131–45. 10.1074/jbc.M702824200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eskelinen EL. Roles of LAMP-1 and LAMP-2 in lysosome biogenesis and autophagy. Mol Aspects Med. (2006) 27:495–502. 10.1016/j.mam.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manchanda M, Roeb E, Roderfield M, Gupta SD, Das P, Singh R, et al. P0109: elevation of cathepsin L and B expression in liver fibrosis: a study in mice models and patients. J Hepatol. (2015) 62:S341–2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai J, Li J, Zhou Y, Wang J, Li J, Cui L, et al. Staphylococcus aureus facilitates its survival in bovine macrophages by blocking autophagic flux. J Cell Mol Med. (2020) 24:3460–8. 10.1111/jcmm.15027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao X, Zhang Z, Li Y, Shen P, Hu X, Cao Y, et al. Selenium deficiency facilitates inflammation following S. aureus infection by regulating TLR2-related pathways in the mouse mammary gland. Biol Trace Element Res. (2016) 172:449–57. 10.1007/s12011-015-0614-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khoramrooz SS, Mansouri F, Marashifard M, Hosseini SAAM, Ganavehei B, Gharibpour F, et al. Detection of biofilm related genes, classical enterotoxin genes and agr typing among Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine with subclinical mastitis in southwest of Iran. Microb Pathog. (2016) 97:45–51. 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnaith A, Kashkar H, Leggio SA, Addicks K, Krönke M, Krut O. Staphylococcus aureus subvert autophagy for induction of caspase-independent host cell death. J Biol Chem. (2007) 282: 2695–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masud S, Prajsnar TK, Torraca V, Lamers GEM, Benning M, Van Der Vaart M, et al. Macrophages target Salmonella by Lc3-associated phagocytosis in a systemic infection model. Autophagy. (2019) 15:796–812. 10.1080/15548627.2019.1569297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujiwara N, Usui T, Ohama T, Sato K. Regulation of Beclin 1 protein phosphorylation and autophagy by protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) and death-associated protein kinase 3 (DAPK3). J Biol Chem. (2016) 291:10858–66. 10.1074/jbc.M115.704908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papáèková Z, Daòková H, Páleníèková E, Kazdová L, Cahová M. Effect of short- and long-term high-fat feeding on autophagy flux and lysosomal activity in rat liver. Physiol Res. (2012) 61(Suppl. 2):S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchesi N, Thongon N, Pascale A, Provenzani A, Koskela A, Korhonen E, et al. Autophagy stimulus promotes early HuR protein activation and p62/SQSTM1 protein synthesis in ARPE-19 cells by triggering Erk1/2, p38(MAPK), and JNK kinase pathways. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. (2018) 2018:4956080. 10.1155/2018/4956080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goode A, Butler K, Long J, Cavey J, Scott D, Shaw B, et al. Defective recognition of LC3B by mutant SQSTM1/p62 implicates impairment of autophagy as a pathogenic mechanism in ALS-FTLD. Autophagy. (2016) 12:1094–104. 10.1080/15548627.2016.1170257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Zhou Y, Zhu Q, Zang H, Cai J, Wang J, et al. Staphylococcus aureus induces autophagy in bovine mammary epithelial cells and the formation of autophagosomes facilitates intracellular replication of Staph. aureus.J Dairy Sci. (2019) 102:8264–72. 10.3168/jds.2019-16414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yue W, Hamaï A, Tonelli G, Bauvy C, Nicolas V, Tharinger H, et al. Inhibition of the autophagic flux by salinomycin in breast cancer stem-like/progenitor cells interferes with their maintenance. Autophagy. (2013) 9:714–29. 10.4161/auto.23997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu W, Xin L, Soong L, Zhang K. Sphingolipid degradation by Leishmania major is required for its resistance to acidic pH in the mammalian host. Infect Immun. (2011) 79:3377–87. 10.1128/IAI.00037-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chikte S, Panchal N, Warnes G. Use of LysoTracker dyes: a flow cytometric study of autophagy. Cytometry Part A. (2014) 85:169–78. 10.1002/cyto.a.22312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierzyñska−Mach A, Janowski PA, Dobrucki JW. Evaluation of acridine orange, lysotracker red, and quinacrine as fluorescent probes for long−term tracking of acidic vesicles. Cytometry A. (2014) 85:729–37. 10.1002/cyto.a.22495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haidar B, Kiss RS, Sarovblat L, Brunet R, Harder C, Mcpherson R, et al. Cathepsin D, a lysosomal protease, regulates ABCA1-mediated lipid efflux. J Biol Chem. (2006) 281:39971–81. 10.1074/jbc.M605095200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liton PB, Lin Y, Epstein DL. Cytosolic release of cathepsin d resulting from lysosomal permeabilization is involved in H2O2-induced cell death in porcine trabecular meshwork (TM) cells: potential relevance to glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2010) 51:5839. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sigloch FC, Tholen M, Gomez-Auli A, Biniossek ML, Reinheckel T, Schilling O. Proteomic analysis of lung metastases in a murine breast cancer model reveals divergent influence of CTSB and CTSL overexpression. J Cancer. (2017) 8:4065–74. 10.7150/jca.21401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.