Encore Anxiety 重複演出焦慮

Fear of disappointing people you've already impressed is more paralyzing than fear of impressing nobody at all.

害怕令已經被你打動的人感到失望,比起害怕根本無法給人留下印象還要更令人麻痺。

There’s a special kind of hell for anyone who has tasted appreciation for their work, especially in public. It’s not the obvious torment of abject failure. That’s too straightforward, too clean. Rather, it’s the exquisite agony of knowing people are waiting for you to be brilliant again, and you’re not entirely sure how you pulled it off the first time. I’ve come to think of this, affectionately, as encore anxiety.

對於曾經品嘗過作品受到讚賞的人來說,特別是在公開場合,有一種特殊的折磨。這不是赤裸裸的失敗帶來的痛苦。那太直接,太乾淨俐落。反而是一種精緻的痛苦,那就是知道人們正等著你再次展現光芒一次 ,而你不確定自己當初是如何成功的。 我親切地稱之為重複演出焦慮 。

The first time I tried stand-up comedy, I was strategic about it. I picked an open mic night at a club I didn’t belong to in a neighborhood I’d never visit — no chance of running into anyone from my real life. I was nervous about making a fool of myself, yet there was a lightness in knowing I could fail anonymously.

第一次嘗試站立式喜劇時,我是有策略地進行的。我選擇了一個我不熟悉的俱樂部裡的即興表演之夜,在一個我從未造訪的社區——絕無可能遇到生活中認識的人。我很緊張會出醜,但同時又因為可以匿名失敗而感到輕鬆。

My set lasted three minutes. My closer landed a loud groan that devolved into laughter as the audience connected the dots. To my surprise, I did well. By the second time, I was plugged into the local comedy circuit, knew some regulars, had even made a friend. My timing was better. Yet I found myself more nervous.

The first time, I performed for nobody. The second time, I performed for people who expected something of me. And the moment you’re expected, you’re exposed.

第一次,我是在無人的情況下表演。第二次,我是為已經對我有期待的人表演。而當你被寄予期望的那一刻,你就已經暴露在眾目睽睽之下。

Encore anxiety haunts every creative field. Success creates pressure to repeat, and that pressure quickly paralyzes. Startup founders, novelists, podcasters, posters. Musicians after a breakout album, filmmakers after a hit, athletes after a record season. Most writers I know get encore anxiety — a great essay burdens the next.

迴響焦慮困擾每一個創意領域。成功會帶來重複的壓力,而這種壓力很快就會使人麻痺。創業者、小說家、播客主持人、貼文者。 在突破性專輯之後的音樂人,暢銷電影之後的電影製作人,破紀錄賽季之後的運動員。我認識的大多數作家都有迴響焦慮——一篇出色的文章會給下一篇帶來負擔。

Impostor syndrome gets all the attention, but encore anxiety is its cruel foil: not the fear that you're a fraud, but the fear that you're genuine and still might not be able to prove it. The difference in attribution matters to the dominant psychology at play: the impostor fears their past success was luck; the encore-anxious person believes it was skill and yet fears they can't summon it again at will.

冒名者症候群備受關注,但迴響焦慮是其殘酷的反面:不是害怕自己是個騙子,而是擔心自己是真誠的,但仍可能無法證明。 歸因的差異對當前的心理狀態很重要:冒名者害怕過去的成功只是運氣;而迴響焦慮的人相信那是技巧,卻又害怕無法再次隨意召喚這種能力。

Either way, there’s a focus on what others are thinking. When no one knows your name, there’s infinite possibility. Anonymity is strangely freeing. Hopeless enough to be hopeful. Affords you the luxury of unlimited creative risk. But the moment you impress someone, namely someone you respect, you've created something scarier than failure: personal expectation. (This isn’t just a professional phenomenon; it applies to your personal life too.)

無論如何,重點都在於他人的想法。當沒人知道你的名字時,可能性是無限的。匿名竟然有一種奇怪的自由感。絕望到足以保持希望。它給你無限創意風險的奢侈。但當你給某人留下印象時,尤其是你尊敬的人,你創造出比失敗更可怕的東西: 個人期望 。(這不僅是職業現象,也適用於個人生活。)

You start thinking of your creative reputation like a stock portfolio. With no track record, it's worth zero. You can take any risk because bad work costs nothing; it's actually good for you. But once you create value — a $100 idea, a $1000 hit — everything changes. Zero-value portfolios are fearless. It’s the valuable ones that are fragile. Every new asset you introduce becomes a potential market correction.

你開始把創意聲譽看作一個投資組合。當你還沒有任何成績紀錄時,它的價值為零。你可以嘗試任何風險,因為不好的作品不會造成任何損失; 這反而對你有益 。但一旦你創造了價值——一個百元的點子,一個千元的爆款——一切都會改變。 零價值的投資組合是無所畏懼的。反而是有價值的投資組合最為脆弱。 你引入的每一個新資產都可能成為市場調整的潛在觸發點。

Social media democratized this torture. The pressure to go viral is one thing; post-viral paralysis is another. You stare at the compose box trying to replicate lightning, wondering if anything will live up to that moment the algorithm smiled at you.

社交媒體讓這種折磨大眾化了。追求病毒式傳播是一回事;病毒式貼文後的癱瘓是另一回事。你盯著編輯框試圖重現那一瞬間的閃電,不知道是否有任何內容能再次得到演算法的青睞。

The cruelty is compounded by converging forces. The algorithm punishes latency; skip a week and it abandons you. Humans do too; your fans and followers expect consistency and constant output. You’re caught between maintaining momentum and maintaining quality, with neither machines nor people tolerating the pauses, the meandering, the volatility that novelty demands. Add to this that we're living in a time when it feels like every permutation of everything has already been done.

這種殘酷更是被匯聚的力量加劇。演算法懲罰遲緩;跳過一週,它就會拋棄你。人類也是如此;你的粉絲和追隨者期待持續性和不間斷的產出。你被夾在維持 momentum 和維持品質之間,機器和人都不能容忍新穎事物所需的停頓、迂迴和波動。更重要的是,我們生活在一個似乎每種可能性都已經被嘗試過的時代。

The audience infiltrates the process. You feel their presence, second-guessing every creative act before it's taken. Your private thinking space becomes a stage for an imagined crowd. We’re not far off from having AI versions of our audience embedded in our workflow. The damage is the loss of internal creative solitude.

觀眾滲透了創作過程。你感受到他們的存在,在每一個創意行動還未發生前就開始猶豫不決。你私密的思考空間變成了想像中群眾的舞台。我們離將 AI 版本的觀眾嵌入工作流程已經不遠了。 這造成的傷害是失去內在創意的獨處。

Perhaps worse than the primary anxiety is the secondary drain: the cognitive load of parsing competing criteria from your many constituents. Constant calibration and self-monitoring drains the spontaneity that first made your work compelling.

也許比最初的焦慮更糟的是次要的耗損:來自各方利益相關者的不同標準所造成的認知負擔。持續的調整和自我監控,耗盡了最初使你的作品引人入勝的自發性。

Constraints can be creative tools — a signature format or a recognizable voice or point of view. But these constraints should emerge from your authentic interests, not from a desire to safeguard your audience's comfort.

限制可以成為創意的工具——一種特定的格式、一個辨識度高的聲音或觀點。但這些限制應該源自於你真正的興趣,而不是為了維護觀眾的舒適感。

Success transforms your audience into an anonymous "they" that become your creative authority. You stop asking what you want to make. You start asking what one with an audience should make. This slides into audience capture — slowly reshaping your work to match expectations, even pushing you to abandon what would make you happy in pursuit of what would fit your brand.

成功會讓你的觀眾變成一個匿名的「他們」,成為你創作的權威。你不再追問自己想要製作什麼,而是開始思考作為有觀眾的創作者應該製作什麼。這逐漸滑向了觀眾俘獲 ——慢慢地重塑你的作品以符合預期,甚至迫使你放棄能讓自己快樂的事物,只為迎合自己的品牌形象。

It’s enlightening to note down who you fear disappointing most. For some people, fear might come from abstract social judgment at scale. For many though, there is a tiered hierarchy of people whose opinions they really care about.

值得留意的是誰是你最害怕令其失望的人。 對某些人來說,恐懼可能源自大規模的抽象社會評判。不過,對很多人而言,他們真正在意的是一個層級分明的意見名單。

You might have tens of thousands of readers but there are really just 10 people whose esteem you hold in high regard at a given time (like a Dunbar’s number for whose opinion of your work you really give a f*ck about). It’s incredibly useful to know who makes this cut and why, and to interrogate whether they even should.

你可能擁有數萬名讀者,但在某個特定時刻,真正令你在意的其實只有 10 個人(就像是丹巴數理中,你真正在意其作品評價的那群人)。了解誰進入了這個圈子,以及為什麼,並質疑他們是否值得,這是相當有用的。

If you're any good at what you do, you face encore anxiety often. In one way, it’s helpful to correlate it to ego, to be self-aware of the cycles in which you feel like you’ve something more to lose than ‘usual.’ What’s the expression? Nothing is ever as good as it seems or as bad as it seems? Nothing definitively makes you and nothing definitively breaks you. Temper the upswings to temper the downswings.

如果你在自己的專業領域很有成就,你經常會面臨「重複演出的焦慮」。從某種程度上說,將這種焦慮與自我聯繫起來是有幫助的,對於自身會感到比「平常」更有可能失去的循環保持自覺。 有句話怎麼說來著?事情從來不會像看起來的那麼好,也不會像看起來的那麼糟。 沒有什麼東西能徹底定義你,也沒有什麼能徹底摧毀你。 調節高潮,就是在調節低谷。

The best seem to understand the traps intuitively, or at least learn to over time. They treat each piece of work as independent rather than sequential. They internalize that there will be peaks and valleys, time in the light and in the dark. They figure out what factors serve as shields against this feeling (e.g. releasing work with a reputable organization or co-signers backing them).

They've learned that trying to protect past work is the enemy of future work. Creation and preservation require fundamentally different mindsets, often at odds.

Success creates a choice: protect what you've built or build what comes next. Part of creative growth is accepting that some people who loved your early work will hate what you become, and that's exactly as it should be. Disappoint people.

成功帶來一個選擇:守護你已建立的成果,或是開創下一個階段。創意成長的一部分,就是接受某些喜愛你早期作品的人會討厭你未來的模樣,而這正是理所當然的。 令人失望吧。

Your best work emerged from a personal research agenda, not a commercial one. Stop trying to please an audience of strangers and start pleasing different versions of yourself, starting with the version who was curious before there was a reputation to protect, who was obliviously obsessed and freely exploring.

Practice creative archaeology: dig up your native impulses.

Encore anxiety boils down to this: the fear of disappointing people you've already impressed is more paralyzing than the fear of impressing nobody at all.

Success changes the game you're playing without telling you. But your previous success wasn't a formula to replicate; it was an outcome of conditions that no longer exist, namely the condition of not having any audience to please. It’s easy to start managing perception instead of pursuing truth. And yet, half the time, your 'audience anxiety' is just you knowing the work isn't good enough for you.

Note: One of the reasons I wanted to write this essay is that the very concept of encore anxiety requires you to acknowledge that you’ve done something interesting or successful or noteworthy already — something that deserves an encore. Polite society tends to push people to avoid this acknowledgement, but we’d all be better off being honest, about our losses and wins, and our goals.

The antidote to encore anxiety isn’t caring less about your work or the people judging it, but caring more about truthseeking — whatever that means to you as the artist. When you're genuinely pursuing truth in your domain, the audience becomes secondary to the investigation. The work itself becomes more interesting than the watchers.

Craft over calibration. Problems over people. Reps over reputation.

Thanks to Josh Lee for the nudge to write about these phenomena.

If you liked this essay, consider sharing with a friend or community that may enjoy it too.

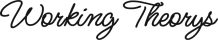

Cover art: Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), David Hockney, 1972.

This is one of the nicest post I have read in recent times. It answers so many of my questions. It’s so easy to get carried away in people pleasing and why it isn’t easy the other way around? Constant conscious fight between the perception and seeking truth exhausts me at times.

"Managing perception instead of pursuing truth" can easily become 99% of corporate work if you are not careful.