Abstract 摘要

The symbiosis potential of microalgae and yeast is inherited with distinct advantages, providing an economical venue for their scale-up application. To assess the advantage of the mixed culture of microalgae Chlorella vulgaris and yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for treatment of liquid digestate of yeast industry (YILD) and cogeneration of biofuel feedstock, the cell growth characteristic, the nutrient removal efficiency, the energy storage potential of the mono, and mixed culture were investigated. The results indicated that the biomass concentration of the mixed culture (1.39–1.56 g/L of 5 times dilution group and 1.23–1.53 g/L of 10 times dilution group) was higher than those of mono cultures. The NH3-N and SO42− removal rates of the mixed culture were superior to mono cultures. Besides the higher lipid yield (0.073–0.154 g/L of 5 times dilution group and 0.112–0.183 g/L of 10 times dilution group), the higher yield of higher heating value (20.06–29.76 kJ/L of 5 times dilution group and 21.83–29.85 kJ/L of 10 times dilution group) was also obtained in the mixed culture. This study provides feasibility for remediation of YILD and cogeneration of biofuel feedstock using the mixed culture of microalgae and yeast.

微藻与酵母的共生潜力具有显著优势,为其规模化应用提供了经济途径。为了评估微藻小球藻(*Chlorella vulgaris*)与酵母油脂酵母(*Yarrowia lipolytica*)的混合培养在处理酵母工业液态消化液(YILD)以及生物燃料原料共生产方面的优势,研究了单一培养和混合培养的细胞生长特性、营养去除效率及能量储存潜力。结果表明,混合培养的生物量浓度(5 倍稀释组为 1.39–1.56 g/L,10 倍稀释组为 1.23–1.53 g/L)高于单一培养。混合培养的 NH₄⁺-N 和 SO₄²⁻去除率优于单一培养。此外,混合培养的脂质产量较高(5 倍稀释组为 0.073–0.154 g/L,10 倍稀释组为 0.112–0.183 g/L),且获得了更高的高热值产量(5 倍稀释组为 20.06–29.76 kJ/L,10 倍稀释组为 21.83–29.85 kJ/L)。该研究为利用微藻和酵母的混合培养修复 YILD 及共生产生物燃料原料提供了可行性。

Similar content being viewed by others

类似内容正在被其他人浏览中。

Explore related subjects

探索相关主题

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.通过机器学习推荐,发现研究人员在相关主题上的最新文章和新闻。

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction 介绍

The number of yeast industry is expanding in China during the last decade due to the increasing demand of export and the change of the mode of Chinese traditional fermented food that inevitably generate a large quantity of high-strength liquid wastes namely yeast wastewater [1]. Yeast wastewater is dark color and contains a higher amount of total nitrogen (TN), and various non-biodegradable organic pollutants [2]. The development of easily operative methods for the treatment of yeast wastewater before runoff into environment is a challenging task for scientists and environmental engineers as yeast wastewater is characterized with very high chemical oxygen demand (COD) (4000–130,000 mg/L) and biochemical oxygen demand (BODx) (200–96,000 mg/L) [3]. In 2010, China produces 240,000 t yeast, and it was reported that the production is 1 t of yeast process about 100 m3 of wastewater. According to the guidelines of Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China, dairy farms, industries (e.g., food/ beverage, breweries), and municipalities are required to meet the standards for the handling and recycling of wastewater (especially nutrients, phosphorus, and nitrogen) prior discharge wastewater that poses serious environmental challenges to the receiving water bodies. According to the national standard of China “Discharge standard of water pollutants for yeast industry (GB 25462-2010),” the limit value of COD, TN, TP, and NH3-N is 400, 40, 2.0, and 25 mg/L, respectively, for indirect discharge which refers to the discharge of pollutants from the factory to the public sewage treatment system. So far, there is no simple, robust, and easily adaptable process available for treating the yeast wastewater. The yeast factories in China have developed and improved conventional anaerobic treatment processes to treat wastewater. Although the anaerobic processing can recover most organic matter in the form of methane, it is limited to the removal of nitrogen and phosphorus. The liquid digestate needs further chemical and physical-chemical treatment to meet the discharge standard; however, chemical treatment of wastewaters is expensive and can pose long-term environmental effects.

过去十年间,由于出口需求的增加以及中国传统发酵食品模式的改变,中国的酵母产业正在迅速扩展,这不可避免地产生了大量高浓度液体废水,即酵母废水[1]。酵母废水颜色深、总氮(TN)含量高,并含有多种难降解有机污染物[2]。由于酵母废水的化学需氧量(COD)极高(4000–130,000 mg/L)和生化需氧量(BOD)极高(200–96,000 mg/L)[3],因此在排放到环境之前开发便捷的处理方法对科学家和环境工程师来说是一项具有挑战性的任务。2010 年,中国生产了 24 万吨酵母,据报道,每生产 1 吨酵母会产生约 100 立方米的废水。根据中华人民共和国环境保护部的相关规定,奶牛场、食品/饮料行业、啤酒厂等工业企业和市政管理部门在废水排放前需达到处理和回收标准(尤其是养分、磷和氮的处理)以避免对受纳水体造成严重环境问题。根据中国国家标准《酵母工业水污染物排放标准》(GB 25462-2010),间接排放(即从工厂排放至公共污水处理系统)中 COD、TN、TP 和 NH₃-N 的限值分别为 400、40、2.0 和 25 mg/L。然而,目前尚无简单、可靠且易于适应的酵母废水处理工艺。中国的酵母工厂已经开发并改进了传统的厌氧处理工艺来处理废水。尽管厌氧处理可以以甲烷的形式回收大部分有机物,但对氮和磷的去除效果有限。厌氧处理后的液体消化物需要进一步的化学或物理化学处理才能达到排放标准;然而,废水的化学处理成本高昂,并可能带来长期的环境影响。

The use of microalgae in wastewater treatment and the generation of biomass have been long promoted because many species of microalgae can effectively grow in wastewater using organic carbon and inorganic N and P from wastewater as nutrients and simultaneously can remove access N, P, as well as heavy metals such as Cd and Zn [4, 5]. Microalgae culture conjunction with wastewater treatment can save the cost of wastewater treatment and enhance the economic feasibility and sustainability of microalgae biofuel production [6,7,8]. Therefore, researchers are interested in using anaerobic liquid digestate for microalgae culture [9,10,11]. Most of the reported study used anaerobic liquid digestate from anaerobic treatment industry of livestock wastewater, kitchen wastewater, piggy wastewater, etc.; however, liquid digestate from yeast industry has not been studied.

微藻在废水处理和生物质生成中的应用长期以来受到推崇,因为许多微藻物种能够利用废水中的有机碳以及无机氮(N)和磷(P)作为营养物质,在废水中有效生长,同时去除过量的氮、磷以及镉(Cd)、锌(Zn)等重金属[4, 5]。将微藻培养与废水处理结合起来,不仅可以节省废水处理成本,还能提高微藻生物燃料生产的经济可行性和可持续性[6, 7, 8]。因此,研究人员对利用厌氧液态消化液进行微藻培养产生了兴趣[9, 10, 11]。大多数已报道的研究使用的是来自畜禽废水、厨房废水、猪场废水等厌氧处理行业的厌氧液态消化液;然而,来自酵母工业的液态消化液尚未被研究。

Symbiosis of microalgae and yeast was studied by many researchers, and reviews elucidated that due to the higher carbon dioxide available for microalgae for photosynthesis and the higher oxygen availability for heterotrophy of yeast, the combination of yeast and microalgae culture in one process shows many significant advantages over the mono microalgae culture, like higher yield of high value products, such as lipid, and faster growth rate and higher biomass concentration and removal of organic materials and nutrients from wastewater [12, 13]. A significant number of reports indicate the potential of some kinds of yeasts using glycerol or crude glycerol, generated in the various oleo-chemical facilities employing transformation of vegetable or animal fats, as a carbon source for a plethora of metabolic compounds of value-added production, such as microbial lipids (also called single cell oils, SCO) [14, 15]. In the co-culture of photosynthetic microalgae and heterotrophic yeast process, microalgae act as an O2 generator and provide higher level O2 for the heterotrophic growth of yeast; on the other hand, later produced CO2 by the yeast assimilation of the organic carbon source can be used by microalgae for growth and lipid production [16].

许多研究者研究了微藻与酵母的共生关系,综述表明,由于微藻在光合作用中有更多的二氧化碳可用,以及酵母在异养过程中有更多的氧气可用,将酵母和微藻联合培养在一个过程中相比单一微藻培养具有许多显著优势,例如更高的高价值产品产量(如脂质)、更快的生长速度、更高的生物量浓度以及更高效地去除废水中的有机物和营养物质[12, 13]。大量研究表明,一些酵母能够利用甘油或粗甘油(这些物质是在各种油脂化工工厂通过植物或动物脂肪转化过程中产生的)作为碳源,来生产多种代谢化合物,这些化合物具有增值生产价值,例如微生物脂质(也称为单细胞油,SCO)[14, 15]。在光合微藻与异养酵母的共培养过程中,微藻作为氧气的生成者,为酵母的异养生长提供更高水平的氧气;另一方面,酵母通过吸收有机碳源产生的二氧化碳可以被微藻用来生长和生产脂质[16]。

Exploiting the reciprocity between yeast and microalgae strains in the mixed culture system with low-value substances is an innovative strategy to govern high biomass and/or lipid productivity and decrease the cost of feedstock for biofuel production. The aim of this work was to assess the advantage of the mixed culture of Chlorella vulgaris and Yarrowia lipolytica with YILD as low-value substance. The biotic and abiotic characteristics including the growth of C. vulgaris and Y. lipolytica, the nutrient removal efficiency, and the energy storage potential of the mono and mixed culture system were studied in detail to assess the feasibility of using the mixed culture of microalgae and yeast in the treatment of liquid digestate of yeast industry and cogeneration of biofuel feedstock.

利用酵母菌株和微藻菌株在低价值物质混合培养系统中的互惠关系,是一种创新策略,可以实现高生物质和/或脂质生产率,并降低生物燃料生产中原料的成本。本研究的目的是评估以低价值物质 YILD 为基础的小球藻(*Chlorella vulgaris*)与酵母菌(*Yarrowia lipolytica*)混合培养的优势。研究详细分析了单一培养和混合培养系统中小球藻与酵母菌的生长情况、营养物去除效率以及能量储存潜力的生物和非生物特性,以评估利用微藻与酵母混合培养处理酵母工业液体消化物并协同生产生物燃料原料的可行性。

Material and Methods 材料与方法

Strain 拉紧

Microalgae strain C. vulgaris was purchased from The Microbial Culture Collection at the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan (strain number NIES-227). The axenic culture which sent from Japan was transferred into new C medium and incubated at 25 °C and checked the growth day after day. Repeat the transfers till the steady growth of the culture. The C medium was described as follows: 100 mL medium contained Ca(NO3)2·4H2O 15 mg, KNO3 10 mg, β-Na2 glycerophosphate·5H2O 5 mg, MgSO4·7H2O 4 mg, vitamin B12 0.01 μg, biotin 0.01 μg, thiamine HCl 1 μg, PIV metals, 0.3 mL, and tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane 50 mg. The composition of PIV metals was Na2EDTA·2H2O 100 mg, FeCl3·6H2O 19.6 mg, MnCl2·4H2O 3.6 mg, ZnSO4·7H2O 2.2 mg, CoCl2·6H2O 0.4 mg, Na2MoO4·2H2O 0.25 mg, and distilled water 100 mL. The medium was sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min before use.

小球藻(C. vulgaris)菌株购自日本国立环境研究所微生物菌种保藏中心(菌株编号:NIES-227)。从日本寄来的无菌培养物被转移到新的 C 培养基中,并在 25°C 下培养,每天检查其生长情况。重复转移操作,直到培养物生长稳定为止。C 培养基的成分如下:每 100 mL 培养基中含有 Ca(NO₃)₂·4H₂O 15 mg,KNO₃ 10 mg,β-Na₄甘油磷酸盐·5H₂O 5 mg,MgSO₄·7H₂O 4 mg,维生素 B12 0.01 μg,生物素 0.01 μg,盐酸硫胺素 1 μg,PIV 金属溶液 0.3 mL,以及三羟甲基氨基甲烷 50 mg。PIV 金属溶液的成分为:Na₂EDTA·2H₂O 100 mg,FeCl₃·6H₂O 19.6 mg,MnCl₂·4H₂O 3.6 mg,ZnSO₄·7H₂O 2.2 mg,CoCl₂·6H₂O 0.4 mg,Na₂MoO₄·2H₂O 0.25 mg,以及蒸馏水 100 mL。培养基在 121°C 高温下灭菌 20 分钟后使用。

Yeast stain Y. lipolytica was purchased from Guangdong Microbiology Culture Center at Guangdong Institute of Microbiology, China (strain number GIM2.197). The strain was maintained in YPD medium (glucose 20 g/L, yeast extract 10 g/L, and peptone 20 g/L).

酵母菌株 Y. lipolytica 从中国广东省微生物研究所的广东省微生物菌种保藏中心购买(菌株编号 GIM2.197)。该菌株保存在 YPD 培养基中(葡萄糖 20 g/L、酵母提取物 10 g/L 和蛋白胨 20 g/L)。

Medium and Liquid Digestate of Yeast Industry Wastewater

酵母工业废水的中相和液态消化液

Seed media of C. vulgaris and Y. lipolytica were BG11 and YPD, respectively. The yeast wastewater was collected from the production process of medicinal yeast using sugarcane molasses of Guangdong Wuzhou Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., located in Guangdong Province of China and stored at 4 °C for anaerobic digestion. A 2.5-L anaerobic digester with a working volume of 2 L was utilized for anaerobic digestion. Anaerobic digester was filled with 1 L yeast wastewater and 1 L inoculums, and the pH value was adjusted to 7.20 using 1 mol/L sodium hydroxide. The inoculum was taken from the stable operating mesophilic continuous stirred tank reactor (CSTR), which was fed an artificially prepared substrate containing glucose, starch, cellulose, xylose, yeast powder, and peptone [17]. The anaerobic digester was placed in a water bath at 35 °C for 50 days following nitrogen stripping. The YILD was autoclaved followed by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 5 min. The characteristics of autoclaved liquid digestate are shown in Table 1.

小球藻(C. vulgaris)和脂肪酵母(Y. lipolytica)的种子培养基分别为 BG11 和 YPD。酵母废水取自广东省吴州制药有限公司利用甘蔗糖蜜生产药用酵母的工艺过程,并在 4 °C 下储存以进行厌氧消化。厌氧消化使用了一个 2.5 升的厌氧消化器,其工作体积为 2 升。厌氧消化器中加入了 1 升酵母废水和 1 升接种物,并用 1 mol/L 氢氧化钠将 pH 值调节至 7.20。接种物取自稳定运行的中温连续搅拌釜式反应器(CSTR),该反应器以人工配制的含有葡萄糖、淀粉、纤维素、木糖、酵母粉和蛋白胨的底物为原料[17]。厌氧消化器置于 35 °C 的水浴中进行氮气吹扫后培养 50 天。YILD 经过高压灭菌后,以 6000 rpm 离心 5 分钟。高压灭菌后液体消化物的特性见表 1。

表 1 高压釜处理 YILD 的特性

Experimental Setup 实验设置

The Y. lipolytica was transferred to 250-mL flasks containing 100 mL YPD medium, cultivated at 28 °C and 150 rpm for 36 h, and used as seed culture. The C. vulgaris was transferred to column glass photobioreactor (Ф = 5.5 cm, 70 cm high) containing 500 mL BG11 medium, cultivated at 25 ± 1 °C, and illuminated with white fluorescent lamps at the single side (light intensity of 300 ± 10 μmol photons/m2/s) and supplemented with 2% CO2 at a rate of 1 vvm (volume gas per volume media per minute) at the bottom of the photobioreactor for 3 days, and used as seed culture. The seed cultures were then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min at 25 ± 1 °C and appropriate dilution using sterile water to obtain the high cell density inoculums.

将 Y. lipolytica 转移至含有 100 mL YPD 培养基的 250 mL 锥形瓶中,在 28 °C、150 rpm 条件下培养 36 小时,作为种子培养物。将 C. vulgaris 转移至柱状玻璃光生物反应器(Ф = 5.5 cm,高 70 cm),反应器中含有 500 mL BG11 培养基,在 25 ± 1 °C 条件下培养,并在单侧用白色荧光灯照射(光强为 300 ± 10 μmol photons/m²/s),同时从光生物反应器底部以 1 vvm(每分钟气体体积与培养基体积之比)的速率补充 2% CO₂,培养 3 天,作为种子培养物。随后,将种子培养物在 25 ± 1 °C 条件下以 3000 rpm 离心 5 分钟,并使用无菌水适当稀释,获得高细胞密度的接种液。

The pH of autoclaved YILD was adjusted to 6.7 with HCl solution (4 mol/L) under the aseptic condition before culture the inoculums. The dilution ratios of autoclaved YILD and initial cell density of microalgae and/or yeast are presented in Table 2. Glycerol was added to each treatment with final concentration of 40 mM. All cultures were performed in light shaker using 250-mL flasks with 100 mL working volume and cultivated at 28 ± 1 °C and 150 rpm for 240 h with the light supply of 45 ± 3 μmol photons/m2/s. All the experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the results were presented with the mean including standard deviation unless the specifically states otherwise.

在无菌条件下,将高压灭菌后的 YILD 的 pH 值用盐酸溶液(4 mol/L)调整至 6.7 后用于培养接种物。高压灭菌的 YILD 稀释比和微藻及/或酵母的初始细胞密度列于表 2 中。甘油被加入到每个处理组中,最终浓度为 40 mM。所有培养均在光照摇床上进行,使用 250 mL 烧瓶,工作体积为 100 mL,在 28 ± 1 °C、150 rpm 条件下培养 240 小时,光照强度为 45 ± 3 μmol 光子/m²/s。所有实验均以三次重复进行,结果以均值形式表示,并包含标准偏差,除非另有说明。

表 2 实验设置摘要

Total 8 mL samples were collected at 48, 96, 144, and 240 h. A 20 μL sample was used for microscopic photography and counting. The rest samples were centrifuged (6000 rpm, 5 min), and the supernatant was used for analyses of COD, NH3-N, total inorganic carbon (TIC), total organic carbon (TOC), NO3−, PO43−, SO42−, Cl−, and sediments were used for the cell growth determination. In addition, collected biomass at the end of the culture was lyophilized for lipid analysis and elemental analysis.

总共采集了 8 mL 样品,分别在 48、96、144 和 240 小时时进行采样。其中 20 μL 样品用于显微拍摄和计数。其余样品以 6000 rpm 离心 5 分钟,取上清液用于 COD、NH₄⁺-N、总无机碳(TIC)、总有机碳(TOC)、NO₃⁻、PO₄³⁻、SO₄²⁻、Cl⁻的分析,沉淀部分则用于细胞生长测定。此外,培养结束时收集的生物质经过冷冻干燥用于脂质分析和元素分析。

Analytical Methods **分析方法**

Biomass Measurement 生物量测量

Dry biomass was estimated by gravimetric method; the 3 mL culture was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 5 min at ambient temperature; cell pellets were washed with purified water twice and then incubated at 60 °C until constant weight to determinate the dry biomass weight. Biomass concentration and biomass productivity were calculated according to Qin et al. [7]

通过重量法估算干生物质:取 3 mL 的培养液,在常温下以 6000 rpm 离心 5 分钟;将细胞沉淀用纯净水清洗两次,然后在 60°C 下干燥至恒重,以确定干生物质的重量。生物质浓度和生物质生产率按照 Qin 等人 [7] 的方法计算。

Nutrient Analysis 营养分析

COD and NH3-N were determined using a Hach DR2700 Spectrophotometer (Hach Co., USA) and Hach reagents (CAT No. 2125915 and 2606945) following the manufacturer’s procedure. TC, TIC, and TOC concentrations were determined using the total organic carbon analyzer (Elementar vario TOC, Germany). The concentration of SO42−, Cl−, NO3−, and PO43− was determined by ion chromatography (Metrohm883 Compact IC, Switzerland). The percentage of the removal of nutrients was calculated according to described by Qin et al. [7].

使用 Hach DR2700 分光光度计(Hach 公司,美国)和 Hach 试剂(货号 2125915 和 2606945),按照制造商的操作程序测定 COD 和 NH₄⁺-N。通过总有机碳分析仪(Elementar vario TOC,德国)测定 TC、TIC 和 TOC 浓度。SO₄²⁻、Cl⁻、NO₃⁻和 PO₄³⁻的浓度通过离子色谱仪(Metrohm 883 Compact IC,瑞士)进行测定。营养物去除率按照 Qin 等人[7]描述的方法计算。

Lipid Content Analysis 脂质含量分析

A modified method was applied to quantify the amount of total lipid content [18]. Total 80–100 mg of lyophilized samples were extracted with 2 mL of methanol containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in a water bath shaker at 45 °C for 45 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, and the leftover was re-extracted twice following the same procedures. Then, the leftover was extracted with a 4 mL mixture of hexane and ether (1:1, v/v) 45 °C for 60 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min, after which the supernatant was collected and the leftover was re-extracted twice. All the supernatants were incorporated, and 6 mL of distilled water was added to the combined extracts. The organic phases were combined into a pre-weighed glass tube and evaporated to dryness under the protection of nitrogen. Then, the lipids were lyophilized for 24 h. The total lipids were measured gravimetrically, and the total lipid content and lipid productivity were calculated according to Qin et al. [7].

一种改良的方法被用于定量分析总脂质含量[18]。取 80-100 毫克的冷冻干燥样品,用含 10%二甲基亚砜(DMSO)的 2 毫升甲醇在 45°C 水浴振荡器中提取 45 分钟。混合物以 3000 rpm 离心 10 分钟,收集上清液,残余物按照相同步骤重复提取两次。随后,用 4 毫升正己烷和乙醚(1:1, v/v)的混合液在 45°C 提取 60 分钟。混合物以 3000 rpm 离心 10 分钟,收集上清液,残余物再次重复提取两次。将所有上清液合并后,加入 6 毫升蒸馏水。将有机相收集到预先称重的玻璃管中,并在氮气保护下蒸干,然后将脂质冷冻干燥 24 小时。通过重量法测量总脂质,并根据 Qin 等人[7]的方法计算总脂质含量和脂质生产率。

Elemental Analysis and HHV Calculation

元素分析与高位热值计算

About 5 mg lyophilized samples were used for elemental analysis, using vario EL cube (Elementar, Germany). Based on the elemental composition, HHV was calculated using well-established correlations given by [19].

大约使用了 5 毫克冻干样品进行元素分析,采用的是德国 Elementar 公司的 vario EL cube。根据元素组成,利用文献[19]中提供的成熟相关公式计算了高位热值(HHV)。

Results and Discussion 结果与讨论

Microorganism Growth 微生物生长

The microbial biomass is an important parameter to evaluate the output of the culture system. In this study, the mono C. vulgaris, the mono Y. lipolytica, and the mixed culture were cultivated in YILD with 5 and 10 times dilution and 40 mM glycerol as a carbon source. As shown in Fig. 1, the mixed culture and the mono yeast culture can grow well while the mono microalgae show poor growth performance. The biomass concentrations of the mixed culture groups of 48 h (1.39–1.56 g/L of 5 times dilution and 1.23–1.53 g/L of 10 times dilution) were higher than those of the mono Y. lipolytica (1.15 g/L of 5 times dilution and 1.04 g/L of 10 times dilution, respectively). The biomass productivity on the 48 h of the mixed culture groups (594.38–650.13 mg/L/day of 5 times dilution and 534.00–588.12 mg/L/day of 10 times dilution) was higher than those of the mono Y. lipolytica group (521.00 mg/L/day of 5 times dilution and 464.75 mg/L/day of 10 times dilution, respectively), which is higher than those of the mono microalgae group (79.13 mg/L/day of 5 times dilution and 113.50 mg/L/day of 10 times dilution, respectively) (Table 3). It is widely documented that there was symbiotic relationship between microalgae and yeast in the mixed culture, further providing higher biomass production compared with the mono culture of each organism [12]. Including O2/CO2 exchange, microalgae acted an O2 generator for yeast while yeast provided CO2 to microalgae; the synergistic effect on pH adjustment and substance exchange between microalgae and yeast can contribute to the biomass enhancement [20, 21]. However, there was no considerable increase of biomass in mixed culture when compared with the sum of the two mono cultures, T4 with (T1 + T2) and T9 with (T6 + T7), maybe due to the depletion of nutrients, and the attenuation of light intensity caused by the increased yeast cell which contributes to the poor growth of microalgae in the mixed culture [12, 22].

微生物生物量是评估培养系统产出的重要参数。在本研究中,将单一小球藻(C. vulgaris)、单一酵母(Y. lipolytica)以及混合培养体系分别在稀释 5 倍和 10 倍的 YILD 培养基中,以 40 mM 甘油作为碳源进行培养。如图 1 所示,混合培养体系和单一酵母培养体系表现出良好的生长性能,而单一微藻的生长表现较差。混合培养组在 48 小时的生物量浓度(5 倍稀释为 1.39–1.56 g/L,10 倍稀释为 1.23–1.53 g/L)高于单一酵母组(5 倍稀释为 1.15 g/L,10 倍稀释为 1.04 g/L)。混合培养组在 48 小时的生物量生产率(5 倍稀释为 594.38–650.13 mg/L/day,10 倍稀释为 534.00–588.12 mg/L/day)也高于单一酵母组(5 倍稀释为 521.00 mg/L/day,10 倍稀释为 464.75 mg/L/day),远高于单一微藻组(5 倍稀释为 79.13 mg/L/day,10 倍稀释为 113.50 mg/L/day)(表 3)。已有大量研究表明,微藻与酵母在混合培养中存在共生关系,与单一培养相比,可显著提高生物量产出[12]。这种关系包括氧气(O₂)和二氧化碳(CO₂)的交换:微藻为酵母提供氧气,而酵母为微藻提供二氧化碳。此外,微藻与酵母之间的 pH 调节以及物质交换的协同作用也有助于提高生物量[20, 21]。然而,与两个单一培养的生物量总和相比(T4 与 T1+T2,T9 与 T6+T7),混合培养的生物量并未显著增加,可能是由于营养物质的耗尽以及酵母细胞数量增加导致光强减弱,从而抑制了微藻在混合培养中的生长[12, 22]。

表 3 初始 48 小时的生物质浓度和生产率

The growth of C. vulgaris in this work is poorer than previous reports which were cultivated in different types of liquid digestate such as, when cultured in digested starch wastewater, Yang et al. achieved 3.01 g/L biomass concentration and 580 mg/L/day biomass productivity [23]; 2.05 g/L biomass concentration and 630 mg/L/day biomass productivity were achieved when cultivated in starch processing wastewater [24]; biomass concentration (2.11 g/L) and biomass productivity (450 mg/L/day) were achieved when cultured in sludge liquor concentration [25]. This may be due to the inappropriate nutritional proportion of YILD, especially the presence of high salinity contributors (Cl−, SO42−), to the disadvantage of the growth of C. vulgaris even though the liquid digestate was diluted. The poor growth of performance of C. vulgaris causes that the biomass in the mixed culture system was dominated by the growth of Y. lipolytica which can use glycerol as a carbon source [26]. These experimental outcomes suggested that YILD can be considered as a medium for culture of Y. lipolytica and the mixed culture can as a strategy for the improved the microbial biomass production.

本研究中 **C. vulgaris** 的生长情况比以往报道的差,这些报道中使用了不同类型的液态消化液进行培养。例如,在消化淀粉废水中培养时,Yang 等人获得了 3.01 g/L 的生物量浓度和 580 mg/L/天的生物量生产率 [23];在淀粉加工废水中培养时,获得了 2.05 g/L 的生物量浓度和 630 mg/L/天的生物量生产率 [24];在污泥液浓缩物中培养时,获得了 2.11 g/L 的生物量浓度和 450 mg/L/天的生物量生产率 [25]。这可能是由于 **YILD** 的营养比例不适当,特别是高盐分成分(如 Cl⁻、SO₄²⁻)的存在,即使液态消化液被稀释,也对 **C. vulgaris** 的生长不利。**C. vulgaris** 表现出的较差生长导致混合培养系统中的生物量主要由可以利用甘油作为碳源的 **Y. lipolytica** 的生长所主导 [26]。这些实验结果表明,**YILD** 可被视为 **Y. lipolytica** 的培养基,而混合培养可作为提高微生物生物量生产的一种策略。

Nutrient Removal Comparison

营养物去除比较

Nutrient removal efficiency is an important indicator for evaluating the effectiveness of the microalgae-yeast wastewater cultivation system. Considering that liquid digestate contains nitrogen which is preferably in the form of ammonium and phosphorus which is preferably in the form of phosphate [27], we have chosen NH3-N and PO43− to characterize the nitrogen and phosphorus change situation. Because the PO43− concentration of the autoclaved YILD was 16.16 mg/L and the PO43− of 48 h was not detected, this study mainly focused on the removal of the abundant ingredients including COD, NH3-N, TIC, TOC, Cl−, and SO42−.

营养物去除效率是评估微藻-酵母废水培养系统效果的重要指标。考虑到液体消化液中的氮主要以铵态氮形式存在,磷主要以磷酸盐形式存在 [27],我们选择 NH₄⁺-N 和 PO₄³⁻来表征氮和磷的变化情况。由于高压灭菌处理的 YILD 中 PO₄³⁻浓度为 16.16 mg/L,而 48 小时后未检测到 PO₄³⁻,本研究主要关注丰富成分的去除,包括 COD、NH₄⁺-N、TIC、TOC、Cl⁻和 SO₄²⁻。

Nitrogen is an essential element for various biological substance syntheses (e.g., protein, nucleic acid, and phospholipid) [28]. Nutrient removal efficiencies of biological method mainly depend on the microbial species and the growth status. In the present study, the NH3-N removal effects of the mixed culture were superior to the mono Y. lipolytica culture and the mono C. vulgaris culture (Fig. 2a). This indicated that the microbial uptake may be the main way for NH3-N removal in this work. Furthermore, the NH3-N concentration after 48 h of the mixed culture and the mono yeast culture display increase trend, especially the mono yeast culture. It was reported that ammonia releases a mechanism of protection from yeast cell death during colony development under limited nutrient conditions [29]. This suggested that there was the NH3-N release after 48 h in the mono yeast and the mixed culture, and the presence of microalgae in the mixed culture can alleviate the ammonia release from yeast cell. Comparing with previous studies that achieved 100% removal of NH3-N when cultured Chlorella in liquid digestate of dairy manure [30, 31], the NH3-N removal of mono microalgae culture of this study was not a satisfactory result. This may be due to the poor growth performance of C. vulgaris which limits the use of nitrogen sources. Furthermore, the NH3-N removal of the mixed culture groups shows the gradient variation which in consistent with the initial concentration of microalgae (T5 > T4 > T3 and T10 > T9 > T8). The NH3-N removal rate increases with the increase of dilution ratio (the maximum NH3-N removal rate 80.25% obtained in 10 times dilution group) (Fig. 2a and Table 4).

氮是合成多种生物物质(如蛋白质、核酸和磷脂)的必需元素[28]。生物法的营养去除效率主要取决于微生物种类和其生长状态。在本研究中,混合培养的 NH 3 -N 去除效果优于单一 Y. lipolytica 培养和单一 C. vulgaris 培养(图 2a)。这表明微生物吸收可能是本研究中 NH 3 -N 去除的主要途径。此外,混合培养和单一酵母培养在 48 小时后的 NH 3 -N 浓度呈现增加趋势,尤其是在单一酵母培养中。据报道,在营养有限的条件下,氨释放可作为一种保护机制以防止酵母细胞死亡[29]。这表明,在单一酵母培养和混合培养中,48 小时后出现 NH 3 -N 的释放,而混合培养中微藻的存在可以缓解酵母细胞的氨释放。与先前研究中在奶牛粪便液体消化液中培养小球藻实现 100% NH 3 -N 去除的结果相比[30,31],本研究中单一微藻培养的 NH 3 -N 去除效果并不理想。这可能是由于 C. vulgaris 的生长性能较差,限制了对氮源的利用。此外,混合培养组 NH 3 -N 的去除表现出与初始微藻浓度一致的梯度变化(T5 > T4 > T3 和 T10 > T9 > T8)。NH 3 -N 的去除率随着稀释比例的增加而提高(在 10 倍稀释组中获得了最高的 NH 3 -N 去除率 80.25%)(图 2a 和表 4)。

表 4 COD 和 NH₄⁺-N 去除率

COD in liquid digestate includes volatile fatty acids (VFAs) (mainly in the form of acetic acid) and inorganic carbon sources (mainly in the form of bicarbonate) which can be utilized by microalgae and/or yeast [27, 32]. Glycerol as sole carbon source could enhance biomass and lipid production in the mixed culture of Rhodotorula glutinis and C. vulgaris [22]. In this study, to ensure the growth of microbes, and then fulfill the removal of N and P from the YILD, glycerol (initial concentration 40 mM) as a carbon source was introduced into culture system. The total COD removal effects of the mixed culture (67.05–68.55% of 5 times dilution and 79.23–80.38% of 10 times dilution) were similar to those of the mono Y. lipolytica culture (67.55% of 5 times dilution and 79.40% of 10 times dilution) and significantly better than those of the mono C. vulgaris culture (13.19% of 5 times dilution and 13.88% of 10 times dilution). The total COD removal rate increases with the increase of the dilution ratio (the maximum total COD removal rate of 240 h 80.38% obtained in 10 times dilution group) (Fig. 2b and Table 4). According to the experimental design, glycerol accounted for the proportion of total COD was 69.06 and 81.69% in 5 times diluted and 10 times diluted groups, respectively. The total COD removal rates of the mixed culture and the mono yeast culture after 48 h are similar to the glycerol proportion of total COD. Taking a low content of TIC and the limitations of microalgae in the use of TOC into consideration (Table 5), we concluded that Y. lipolytica plays a dominant role in the removal of total COD and the mixed culture did not significantly enhance the removal efficiency of total COD comparing with the mono Y. lipolytica culture. The relatively low inherent COD removal efficiency can attribute to the percentage of inherent organic carbon matter in the liquid digestate that was inert, and the microalgae and yeast have difficulty using this source because of the more utilizable organic carbon sources already utilized by anaerobic bacteria during anaerobic fermentation [24].

液态消化液中的化学需氧量(COD)包括挥发性脂肪酸(VFAs,主要以乙酸形式存在)和无机碳源(主要以碳酸氢盐形式存在),这些成分可被微藻和/或酵母利用 [27, 32]。甘油作为唯一碳源,可提高红酵母(*Rhodotorula glutinis*)和小球藻(*C. vulgaris*)混合培养体系中的生物质和脂质产量 [22]。在本研究中,为确保微生物的生长并实现从液态消化液(YILD)中去除氮(N)和磷(P),向培养体系中添加了甘油(初始浓度为 40 mM)作为碳源。混合培养体系的 COD 总去除效果(稀释 5 倍时为 67.05%–68.55%,稀释 10 倍时为 79.23%–80.38%)与单一酵母(*Y. lipolytica*)培养体系的效果相似(稀释 5 倍时为 67.55%,稀释 10 倍时为 79.40%),显著优于单一小球藻培养体系的效果(稀释 5 倍时为 13.19%,稀释 10 倍时为 13.88%)。随着稀释倍数的增加,COD 总去除率提高(稀释 10 倍组在 240 小时内的最大 COD 总去除率为 80.38%)(图 2b 和表 4)。根据实验设计,甘油占 COD 总量的比例在 5 倍稀释组和 10 倍稀释组中分别为 69.06%和 81.69%。混合培养体系和单一酵母培养体系在 48 小时后的 COD 总去除率与 COD 总量中甘油的比例相近。考虑到液态消化液中无机碳总量(TIC)含量低以及微藻在利用有机碳总量(TOC)方面的局限性(表 5),我们得出结论:*Y. lipolytica*在 COD 总去除中起主导作用,混合培养体系与单一酵母培养体系相比,并未显著提高 COD 总去除效率。较低的固有 COD 去除效率可以归因于液态消化液中固有有机碳物质的比例,这部分物质较为惰性,而由于厌氧发酵过程中厌氧菌已经利用了更易被利用的有机碳源,微藻和酵母难以利用这些固有有机碳来源 [24]。

表 5 TOC、TIC、Cl − 和 SO 4 2− 的去除效果

Ammonium sulfate, sodium chloride, magnesium sulfate, and other nutrients based on yeast species were added in fermentation system when using molasses as carbon source for yeast product. Hence, large amounts of sulfate and chloride ion consist in yeast wastewater and transfer to the liquid digestate by anaerobic process. Because a high concentration of sulfate and chloride ion is one of the typical characteristics of YILD, assessment of the removal effect of sulfate and chloride ion in the mixed culture system is very necessary. In terms of Cl− removal, the mixed culture shows no obvious advantage compared with the mono culture system, especially the mono yeast culture (Table 5). The removal rate of Cl− of 48 h falls between 10.79 and 15.74% and did not show a tendency to increase with the dilution ratio. Similar to the removal of Cl−, the 48 h SO42− removal rate of the mixed culture (23.47–28.60% of 5 times dilution and 34.78–47.60% of 10 times dilution) shows no obvious advantage compared with the mono yeast culture (22.87% of 5 times dilution and 37.39% of 10 times dilution). However, comparing with the mono microalgae culture (about 15% SO42− removal rate), the mixed culture and the mono yeast culture show an exact advantage of the 48 h SO42− removal rate. Furthermore, the removal rate of the mixed culture and the mono yeast culture increases with the dilution ratio. The inorganic forms of S in liquid digestate consist mainly of sulfates (SO42−). Assimilatory reduction of sulfate ion integrates, together with O2 bioproduction, CO2 fixation, nitrate ion reduction, and N2 fixation, the biological processes essential to aerobic life. The demand for the yeast growth of sulfate ion is more necessary than the chloride ion [33]. Focusing on the removal effect of SO42− and the biomass concentration at 48 h, the theoretical sulfur content of the biomass was between 1.07 and 3.69% if the removal of sulfate is due to the biological assimilation. However, that theoretical sulfur content of biomass at 48 h was definitely greater than the actual sulfur content (0.19–0.65%) at 240 h which was directly determined by elemental analysis (Table 6). Therefore, we speculate that the removal of sulfate is partially due to the biological assimilation or sulfur was released from biomass along with intracellular substances during growth cessation stage.

在以糖蜜为碳源生产酵母的发酵体系中,添加了基于酵母菌种的硫酸铵、氯化钠、硫酸镁等营养物质。因此,大量的硫酸盐和氯离子存在于酵母废水中,并通过厌氧处理转移到液态消化液中。由于高浓度硫酸盐和氯离子是酵母液态消化液(YILD)的典型特征之一,评估混合培养体系中硫酸盐和氯离子的去除效果非常必要。

关于氯离子(Cl − )的去除,混合培养体系与单一培养体系相比(尤其是单一酵母培养体系,见表 5),并未表现出明显优势。在 48 小时内,氯离子(Cl − )的去除率介于 10.79%至 15.74%,且未显示随稀释比例增加而提高的趋势。类似于氯离子(Cl − )的去除情况,混合培养体系对硫酸根离子(SO 4 2− )48 小时去除率(5 倍稀释为 23.47%–28.60%,10 倍稀释为 34.78%–47.60%)与单一酵母培养体系(5 倍稀释为 22.87%,10 倍稀释为 37.39%)相比也未表现出明显优势。然而,与单一微藻培养体系(硫酸根离子去除率约为 15%)相比,混合培养体系和单一酵母培养体系在硫酸根离子(SO 4 2− )48 小时去除率方面确实具有一定优势。此外,混合培养体系和单一酵母培养体系的去除率随稀释比例增加而提高。

液态消化液中的无机硫主要以硫酸盐(SO 4 2− )形式存在。硫酸根离子的同化还原过程与氧(O 2 )的生物生成、二氧化碳(CO 2 )固定、硝酸根离子还原以及氮(N 2 )固定一起构成了对需氧生物至关重要的生物过程。酵母生长对硫酸根离子的需求比对氯离子的需求更为重要[33]。聚焦于硫酸根离子(SO 4 2− )的去除效果及 48 小时的生物量浓度,如果硫酸盐的去除是由于生物同化作用,则理论上 48 小时内生物量的硫含量应介于 1.07%至 3.69%。然而,通过元素分析直接测定的 240 小时生物量实际硫含量仅为 0.19%至 0.65%(见表 6)。因此,我们推测,硫酸盐的去除部分是由于生物同化作用,或者在生长停止阶段,硫随着细胞内物质的释放而从生物量中释放出来。

表 6 脂质和 HHV 输出评估

Overall, although the mixed culture displays exactly advantages compared to the mono culture in inherent pollutant removal from YILD, further researches about selection of strain, glycerol concentration, growth control, and synergy mechanism of mixed culture system should be implemented to improve the pollutant removal effect.

总体而言,尽管与单一培养相比,混合培养在去除 YILD 中的内在污染物方面展现出了明显优势,但仍需进一步研究菌株的选择、甘油浓度、生长控制以及混合培养系统的协同机制,以提升污染物去除效果。

Energy Output Evaluation 能量输出评估

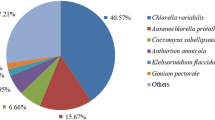

The wastewater can act as low-cost substrate for microbial biomass production, and the obtained microbial biomass can be utilized as renewable energy, feedstuff, and chemical industry [34, 35]. Conjunction with liquid digestate treatment and microbial biofuel product by mixed microalgae and yeast culture is the original intention of this study. Hence, the lipid content and productivity and the HHV, which is an indicator of the amount of energy stored within biomass, were analyzed to evaluate the energy output efficiency of the mono and mixed culture. The lipid content of the mono C. vulgaris culture (14.49% of 5 times dilution and 17.93% of 10 times dilution) was higher than those of the mixed culture (6.66–10.07% of 5 times dilution and 9.21–12.21% of 10 times dilution) and the mono Y. lipolytica culture (5.41% of 5 times dilution and 8.46% of 10 times dilution). The lipid content of the mixed culture showed the gradient variation, T5 > T4 > T3 and T10 > T9 > T8, which in consistence with the initial concentration of microalgae. The lipid content of 10 times dilution is higher than 5 times dilution (Table 6). Although the lipid content of the mixed culture was lower than that of the mono microalgae culture, the lipid yield of the mixed culture (0.073–0.154 g/L of 5 times dilution and 0.112–0.183 g/L of 10 times dilution) was higher than that of the mono microalgae culture in 5 and 10 times diluted groups owing to the higher biomass in the mixed culture. The result was consistent with previous studies, which reported that the mixed culture could enhance the lipid production [12, 20, 36].

废水可以作为低成本的基质用于微生物生物质的生产,而获得的微生物生物质可以用作可再生能源、饲料和化工原料[34, 35]。本研究的初衷是结合液体消化液处理和通过混合微藻与酵母培养生产微生物生物燃料。因此,为了评估单一和混合培养的能源输出效率,分析了脂质含量、生产率以及表示生物质内储存能量的高位热值(HHV)。单一小球藻(C. vulgaris)培养的脂质含量(5 倍稀释时为 14.49%,10 倍稀释时为 17.93%)高于混合培养(5 倍稀释时为 6.66–10.07%,10 倍稀释时为 9.21–12.21%)和单一酵母(Y. lipolytica)培养(5 倍稀释时为 5.41%,10 倍稀释时为 8.46%)。混合培养的脂质含量显示出梯度变化规律,T5 > T4 > T3 和 T10 > T9 > T8,这与初始微藻浓度一致。10 倍稀释的脂质含量高于 5 倍稀释(表 6)。尽管混合培养的脂质含量低于单一微藻培养,但由于混合培养具有更高的生物量,其脂质产量(5 倍稀释时为 0.073–0.154 g/L,10 倍稀释时为 0.112–0.183 g/L)高于单一微藻培养的 5 倍和 10 倍稀释组。该结果与先前研究一致,研究表明混合培养可以提高脂质生产[12, 20, 36]。

Thermochemical conversion is considered as a simpler route to produce biofuels. The technology can be a complement to chemical and biochemical methods for the maximal utilization of microbial biomass [37]. The solid biofuel performance is related to the elemental composition, including carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen content. To assess solid biofuel performance of biomass obtained from mono cultures and the mixed culture, the elemental composition and the estimated HHV, which is a major indicator of biomass quality in energy properties, were analyzed and are presented in Table 6. Excepting HHV values of 10 times dilution group that were higher than 5 times dilution group, respectively, some common characteristics in 5 times dilution and 10 times dilution group were listed as follows: (1) the estimated HHV values of mixed culture (18.24–19.04 MJ/kg of 5 times dilution and 18.98–19.41 MJ/kg of 10 times dilution) were higher than the mono yeast culture (17.25 MJ/kg of 5 times dilution and 17.34 MJ/kg of 10 times dilution) and lower than the mono microalgae culture (20.03 MJ/kg of 5 times dilution and 20.81 MJ/kg of 10 times dilution); (2) the gradient variation which similar to the rules of the NH3-N removal rates, T5 > T4 > T3 and T10 > T9 > T8. Additionally, nitrogen content gradually increased along with the initial concentration of microalgae. The HHV of the mono C. vulgaris in this work (20.03 MJ/kg of 5 times dilution and 20.81 MJ/kg of 10 times dilution) is very close to other reported HHV of Chlorella spp. (20.4 MJ/kg) [38]. However, because the low HHV of Y. lipolytica biomass and the yeast was the main contributor of the biomass from the mixed culture, the HHV of the mixed culture also falls somewhere between the mono C. vulgaris and the mono Y. lipolytica culture. Regarding solid biofuel efficiency, it is necessary to increase the HHV yield of the culture system, requiring a balance between HHV value and the biomass yield. The mixed culture system received perfect HHV yield (20.06–29.76 kJ/L of 5 times dilution and 21.83–29.85 kJ/L of 10 times dilution), which were higher than those of the mono yeast culture and the mono microalgae culture.

热化学转化被认为是生产生物燃料的一种更简单的途径。这项技术可以作为化学和生化方法的补充,以最大限度地利用微生物生物质 [37]。固体生物燃料的性能与元素组成有关,包括碳、氢、氮和氧的含量。为了评估来自单一培养和混合培养的生物质的固体生物燃料性能,对其元素组成和估算的高位热值(HHV)进行了分析,结果见表 6。除 10 倍稀释组的 HHV 值高于 5 倍稀释组外,5 倍稀释和 10 倍稀释组的一些共同特征如下:(1)混合培养的估算 HHV 值(5 倍稀释为 18.24–19.04 MJ/kg,10 倍稀释为 18.98–19.41 MJ/kg)高于单一酵母培养(5 倍稀释为 17.25 MJ/kg,10 倍稀释为 17.34 MJ/kg),但低于单一微藻培养(5 倍稀释为 20.03 MJ/kg,10 倍稀释为 20.81 MJ/kg);(2)梯度变化类似于 NH₄⁺-N 去除率的规律,T5 > T4 > T3 和 T10 > T9 > T8。此外,氮含量随着微藻初始浓度的增加而逐渐升高。本研究中单一小球藻的 HHV(5 倍稀释为 20.03 MJ/kg,10 倍稀释为 20.81 MJ/kg)与其他报道的小球藻属 HHV 值(20.4 MJ/kg)非常接近 [38]。然而,由于 Y. lipolytica 生物质的 HHV 较低,而酵母是混合培养中生物质的主要贡献者,混合培养的 HHV 介于单一小球藻和单一 Y. lipolytica 培养之间。关于固体生物燃料的效率,需要提高培养系统的 HHV 产量,这要求在 HHV 值和生物质产量之间取得平衡。混合培养系统获得了理想的 HHV 产量(5 倍稀释为 20.06–29.76 kJ/L,10 倍稀释为 21.83–29.85 kJ/L),高于单一酵母培养和单一微藻培养的 HHV 产量。

Conclusion 结论

The YILD was observed to be a perfect medium for the mixed culture of C. vulgaris and Y. lipolytica, and the mixed culture improved the microbial biomass production. The mixed culture enhanced the removal efficiency of nitrogen and SO42−. The lipid and HHV yields in the mixed culture were higher than those in mono cultures. This work suggested that the mixed culture of microalgae and yeast could be applied to strengthen the YILD treatment and resource utilization. A credible package of YILD treatment coupling microbial biofuel feedstock production of mixed culture will be fulfilled with further researches for the selection and engineering of suitable strain, mutually benefited growth control, underlying synergy mechanism, and so on.

YILD 被认为是 C. vulgaris 和 Y. lipolytica 混合培养的理想介质,混合培养提高了微生物生物量的产量。混合培养增强了氮和 SO 4 2− 的去除效率。混合培养的脂质和高热值(HHV)产量高于单一培养。这项研究表明,微藻和酵母的混合培养可以用于强化 YILD 的处理和资源利用。通过进一步研究适宜菌株的选择与工程改造、互惠生长控制、潜在协同机制等方面,可实现将 YILD 处理与混合培养微生物生物燃料原料生产相结合的可靠方案。

References 参考文献

Jia, C. H., & Jukes, D. (2013). The national food safety control system of China—a systematic review. Food Control, 32(1), 236–245.

贾春华 (Jia, C. H.) 和朱克斯 (Jukes, D.)。(2013)。中国国家食品安全控制体系——系统性综述。《食品控制》(*Food Control*),**32**(1),236–245。Comelli, R. N., Seluy, L. G., Grossmann, I. E., & Isla, M. A. (2015). The treatment of high-strength wastewater from the sugar-sweetened beverage industry via an alcoholic fermentation process. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 54(31), 7687–7693.

科梅利 (Comelli, R. N.)、塞卢伊 (Seluy, L. G.)、格罗斯曼 (Grossmann, I. E.) 和伊斯拉 (Isla, M. A.)。(2015)。通过酒精发酵工艺处理糖甜饮料行业的高浓度废水。《工业与工程化学研究》(*Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research*),**54**(31),7687–7693。Pirsaheb, M., Rostamifar, M., Mansouri, A. M., Zinatizadeh, A. A. L., & Sharafi, K. (2015). Performance of an anaerobic baffled reactor (ABR) treating high strength baker’s yeast manufacturing wastewater. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers, 47, 137–148.

Pirsaheb, M., Rostamifar, M., Mansouri, A. M., Zinatizadeh, A. A. L., & Sharafi, K. (2015)。厌氧折流板反应器(ABR)处理高浓度酵母生产废水的性能研究。《台湾化学工程学会期刊》,47, 137–148。Alam, M. A., Wan, C., Zhao, X. Q., Chen, L. J., Chang, J. S., & Bai, F. W. (2015). Enhanced removal of Zn(2+) or Cd(2+) by the flocculating Chlorella vulgaris JSC-7. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 289, 38–45.

阿拉姆, M. A., 万春, 赵晓琦, 陈立军, 张金松, & 白凤武. (2015). 絮凝剂小球藻 JSC-7 对 Zn(2+)或 Cd(2+)去除效果的增强研究。《危险材料杂志》, 289, 38–45.Chen, G. Y., Zhao, L., & Qi, Y. (2015). Enhancing the productivity of microalgae cultivated in wastewater toward biofuel production: a critical review. Applied Energy, 137, 282–291.

陈光耀、赵磊、齐悦。(2015)。利用废水培养微藻以提高生物燃料生产的生产率:一项关键综述。《应用能源》,137,282–291。Pittman, J. K., Dean, A. P., Osundeko, O., Pandey, A., Lee, D. J., & Logan, B. E. (2011). The potential of sustainable algal biofuel production using wastewater resources. Bioresource Technology, 102(1), 17–25.

Pittman, J. K.,Dean, A. P.,Osundeko, O.,Pandey, A.,Lee, D. J.,& Logan, B. E.(2011)。利用废水资源实现可持续藻类生物燃料生产的潜力。《生物资源技术》,102(1),17–25。Qin, L., Wang, Z., Sun, Y., Shu, Q., Feng, P., Zhu, L., Xu, J., & Yuan, Z. (2016). Microalgae consortia cultivation in dairy wastewater to improve the potential of nutrient removal and biodiesel feedstock production. Environmental Science & Pollution Research, 23(9), 8379–8387.

秦立、王斋、孙艳、舒琦、冯平、朱丽、徐佳、袁中。(2016)。乳制品废水中微藻共培养促进营养物去除和生物柴油原料生产潜力的提升。《环境科学与污染研究》,23(9),8379–8387。Rawat, I., Kumar, R. R., Mutanda, T., & Bux, F. (2011). Dual role of microalgae: phycoremediation of domestic wastewater and biomass production for sustainable biofuels production. Applied Energy, 88(10), 3411–3424.

Rawat, I., Kumar, R. R., Mutanda, T., & Bux, F. (2011). 微藻的双重作用:家用废水的藻类修复与可持续生物燃料生产的生物质生成。《应用能源》,88(10), 3411–3424。Franchino, M., Tigini, V., Varese, G. C., Mussat, S. R., & Bona, F. (2016). Microalgae treatment removes nutrients and reduces ecotoxicity of diluted piggery digestate. Science of the Total Environment, 569-570, 40–45.

Monlau, F., Sambusiti, C., Ficara, E., Aboulkas, A., Barakat, A., & Carrère, H. (2015). New opportunities for agricultural digestate valorization: current situation and perspectives. Energy & Environmental Science, 8(9), 2600–2621.

Uggetti, E., Sialve, B., Latrille, E., & Steyer, J. P. (2014). Anaerobic digestate as substrate for microalgae culture: the role of ammonium concentration on the microalgae productivity. Bioresource Technology, 152(1), 437–443.

Ling, J., Nip, S., Cheok, W. L., de Toledo, R. A., & Shim, H. (2014). Lipid production by a mixed culture of oleaginous yeast and microalga from distillery and domestic mixed wastewater. Bioresource Technology, 173, 132–139.

Santos, C. A., & Reis, A. (2014). Microalgal symbiosis in biotechnology. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 98(13), 5839–5846.

Tchakouteu, S. S., Kalantzi, O., Gardeli, C., Koutinas, A. A., Aggelis, G., & Papanikolaou, S. (2015). Lipid production by yeasts growing on biodiesel-derived crude glycerol: strain selection and impact of substrate concentration on the fermentation efficiency. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 118(4), 911–927.

Ersahin, M. E., Ozgun H., Dereli R. K., Ozturk, I. (2011). Anaerobic treatment of industrial effluents: An overview of applications. InTech.

Magdouli, S., Brar, S. K., & Blais, J. F. (2016). Co-culture for lipid production: advances and challenges. Biomass & Bioenergy, 92, 20–30.

Li, L., Li, Y., Sun, Y., Yuan, Z., Lv, P., Kang, X., Zhang, Y., & Yang, G. (2018). Influence of the feedstock ratio and organic loading rate on the co-digestion performance of Pennisetum hybrid and cow manure. Energy & Fuels, 32(4), 5171–5180.

Bigogno, C., Khozin-Goldberg, I., Boussiba, S., Vonshak, A., & Cohen, Z. (2002). Lipid and fatty acid composition of the green oleaginous alga Parietochloris incisa, the richest plant source of arachidonic acid. Phytochemistry, 60(5), 497–503.

Friedl, A., Padouvas, E., Rotter, H., & Varmuza, K. (2005). Prediction of heating values of biomass fuel from elemental composition. Analytica Chimica Acta, 544(1–2), 191–198.

Zhang, Z., Ji, H., Gong, G., Zhang, X., & Tan, T. (2014). Synergistic effects of oleaginous yeast Rhodotorula glutinis and microalga Chlorella vulgaris for enhancement of biomass and lipid yields. Bioresource Technology, 164(7), 93–99.

Cheirsilp, B., Suwannarat, W., & Niyomdecha, R. (2011). Mixed culture of oleaginous yeast Rhodotorula glutinis and microalga Chlorella vulgaris for lipid production from industrial wastes and its use as biodiesel feedstock. New Biotechnology, 28(4), 362–368.

Cheirsilp, B., Kitcha, S., & Torpee, S. (2012). Co-culture of an oleaginous yeast Rhodotorula glutinis and a microalga Chlorella vulgaris for biomass and lipid production using pure and crude glycerol as a sole carbon source. Annals of Microbiology, 62(3), 987–993.

Yang, L., Tan, X., Li, D., Chu, H., Zhou, X., Zhang, Y., & Yu, H. (2015). Nutrients removal and lipids production by Chlorella pyrenoidosa cultivation using anaerobic digested starch wastewater and alcohol wastewater. Bioresource Technology, 181, 54–61.

Tan, X., Chu, H., Zhang, Y., Yang, L., Zhao, F., & Zhou, X. (2014). Chlorella pyrenoidosa cultivation using anaerobic digested starch processing wastewater in an airlift circulation photobioreactor. Bioresource Technology, 170(5), 538–548.

Åkerström, A. M., Mortensen, L. M., Rusten, B., & Gislerød, H. R. (2014). Biomass production and nutrient removal by Chlorella sp. as affected by sludge liquor concentration. Journal of Environmental Management, 144(21), 118–124.

Sestric, R., Munch, G., Cicek, N., Sparling, R., & Levin, D. B. (2014). Growth and neutral lipid synthesis by Yarrowia lipolytica on various carbon substrates under nutrient-sufficient and nutrient-limited conditions. Bioresource Technology, 164(7), 41–46.

Xia, A., & Murphy, J. D. (2016). Microalgal cultivation in treating liquid digestate from biogas systems. Trends in Biotechnology, 34(4), 264–275.

Xu, J., Zhao, Y., Zhao, G., & Zhang, H. (2015). Nutrient removal and biogas upgrading by integrating freshwater algae cultivation with piggery anaerobic digestate liquid treatment. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 99(15), 6493–6501.

Vachova, L., & Palkova, Z. (2005). Physiological regulation of yeast cell death in multicellular colonies is triggered by ammonia. Journal of Cell Biology, 169(5), 711–717.

Wang, L. A., Li, Y. C., Chen, P., Min, M., Chen, Y. F., Zhu, J., et al. (2010). Anaerobic digested dairy manure as a nutrient supplement for cultivation of oil-rich green microalgae Chlorella sp. Bioresource Technology, 101(8), 2623–2628.

Wang, L., Wang, Y., Chen, P., & Ruan, R. (2010). Semi-continuous cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris for treating undigested and digested dairy manures. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 162(8), 2324–2332.

Coelho, M. A. Z., Amaral P. F. F., Belo I. (2010). Yarrowia lipolytica: An industrial workhorse. Formatex.

Trenčevski, K., & Kera, S. (2013). Identification of the sulphate ion as one of the key components of yeast spoilage of a sports drink through genome-wide expression analysis. Journal of General and Applied Microbiology, 59(3), 227–238.

Bajpai, P. (2017). Microorganisms used for single-cell protein production. In: Single cell protein production from lignocellulosic biomass. SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science. Springer.

Qin, L., Liu, L., Zeng, A. P., & Wei, D. (2017). From low-cost substrates to single cell oils synthesized by oleaginous yeasts. Bioresource Technology, 245(Pt B), 1507–1519.

Yen, H. W., Chen, P. W., & Chen, L. J. (2015). The synergistic effects for the co-cultivation of oleaginous yeast-Rhodotorula glutinis and microalgae-Scenedesmus obliquus on the biomass and total lipids accumulation. Bioresource Technology, 184, 148–152.

Vardon, D. R., Sharma, B. K., Blazina, G. V., Rajagopalan, K., & Strathmann, T. J. (2012). Thermochemical conversion of raw and defatted algal biomass via hydrothermal liquefaction and slow pyrolysis. Bioresource Technology, 109, 178–187.

Rizzo, A. M., Prussi, M., Bettucci, L., Libelli, I. M., & Chiaramonti, D. (2013). Characterization of microalga Chlorella as a fuel and its thermogravimetric behavior. Applied Energy, 102(2), 24–31.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21606230), the Sciences and Technology of Guangzhou (Grant No. 201704030084), the Natural Science Foundation for research team of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2016A030312007), the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong (Grant No. 2015A020216003, 2016A010105001), and the National Key Research and Development Program-China (2016YFB0601004). This work is partly supported by the 111 Project (B17018).

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, L., Wei, D., Wang, Z. et al. Advantage Assessment of Mixed Culture of Chlorella vulgaris and Yarrowia lipolytica for Treatment of Liquid Digestate of Yeast Industry and Cogeneration of Biofuel Feedstock. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 187, 856–869 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-018-2854-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-018-2854-8

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ); 10 times diluted group: (

); 10 times diluted group: ( ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ).

).

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ); 10 times diluted group: (

); 10 times diluted group: ( ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ).

).