Summary 摘要

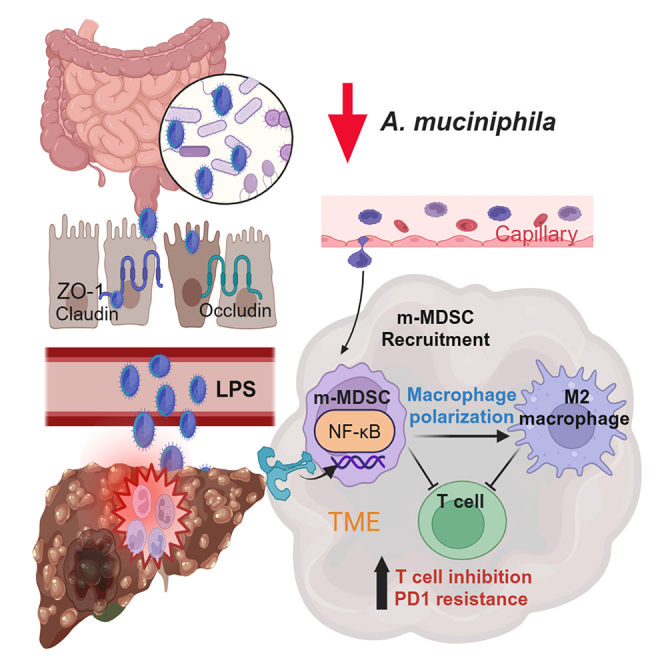

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are not effective for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)-hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients, and identifying the key gut microbiota that contributes to immune resistance in these patients is crucial. Analysis using 16S rRNA sequencing reveals a decrease in Akkermansia muciniphila (Akk) during MAFLD-promoted HCC development. Administration of Akk ameliorates liver steatosis and effectively attenuates the tumor growth in orthotopic MAFLD-HCC mouse models. Akk repairs the intestinal lining, with a decrease in the serum lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and bile acid metabolites, along with decrease in the populations of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (m-MDSCs) and M2 macrophages. Akk in combination with PD1 treatment exerts maximal growth-suppressive effect in multiple MAFLD-HCC mouse models with increased infiltration and activation of T cells. Clinically, low Akk levels are correlated with PD1 resistance and poor progression-free survival. In conclusion, Akk is involved in the immune resistance of MAFLD-HCC and serves as a predictive biomarker for PD1 response in HCC.

免疫检查点抑制剂对代谢功能障碍相关脂肪性肝病(MAFLD)-肝细胞癌(HCC)患者疗效不佳,识别导致这类患者免疫抵抗的关键肠道菌群至关重要。16S rRNA 测序分析显示,在 MAFLD 促进的 HCC 发展过程中,嗜黏蛋白阿克曼菌(Akk)数量减少。给予 Akk 可改善肝脏脂肪变性,并有效抑制原位 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型的肿瘤生长。Akk 能修复肠道屏障,伴随血清脂多糖(LPS)和胆汁酸代谢物水平下降,同时单核细胞来源的髓系抑制细胞(m-MDSCs)和 M2 型巨噬细胞数量减少。Akk 联合 PD1 治疗在多种 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型中产生最大肿瘤抑制效果,同时促进 T 细胞浸润和活化。临床数据显示,低 Akk 水平与 PD1 耐药性和较差的无进展生存期相关。综上所述,Akk 参与 MAFLD-HCC 的免疫抵抗机制,可作为 HCC 患者 PD1 治疗反应的预测性生物标志物。

Keywords: Akkermansia muciniphila, gut microbiota, HCC, immune checkpoint therapies, MAFLD

关键词:Akkermansia muciniphila(嗜黏蛋白阿克曼菌),肠道微生物群,肝细胞癌(HCC),免疫检查点疗法,代谢相关脂肪性肝病(MAFLD)

Graphical abstract 图文摘要

Highlights 亮点

-

•

Decreased Akk level is crucial for the development of MAFLD-induced HCC

嗜黏蛋白阿克曼菌水平下降是 MAFLD 诱发肝细胞癌发展的关键因素 -

•

Akk complements the therapeutic efficacy of PD1 therapy in MAFLD-induced HCC

阿克曼菌增强 PD1 疗法对 MAFLD 诱发肝癌的疗效 -

•

Akk induces T cell infiltration via suppression of m-MDSCs and M2 macrophages

阿克曼菌通过抑制髓系来源抑制细胞和 M2 型巨噬细胞促进 T 细胞浸润 -

•

Akk as a potential biomarker for predicting the PD1 response and survival

阿克曼菌作为预测 PD1 疗效和生存期的潜在生物标志物

Wu et al. have demonstrated that decreased Akk is critical for the development of MAFLD-induced HCC, while its administration enhances the therapeutic efficacy of PD1 treatment through the suppression of m-MDSCs and M2 macrophages. Akk serves as a potential biomarker for predicting PD1 response and patient survival.

吴等人研究证实,阿克曼菌减少是 MAFLD 诱发肝癌发展的关键因素,而补充该菌株可通过抑制髓系来源抑制细胞和 M2 型巨噬细胞来增强 PD1 治疗效果。阿克曼菌可作为预测 PD1 治疗反应和患者生存期的潜在生物标志物。

Introduction 引言

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer in the world, mainly due to the high prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and, recently, the increasing emergence of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD).1,2 MAFLD is a disease of increasing interest, as its prevalence is on the rise; 30% of the adult population and 80% of obese individuals are affected by this disease, rendering it the most common chronic liver disease in developed countries.2 In 2020, a group of international experts issued a statement recommending that MAFLD could be replaced by nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).3 The spectrum of liver pathology extends from simple steatosis, where the only feature is excessive fat deposition within hepatocytes, to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), where additional features include hepatocyte injury, liver inflammation, and pericellular fibrosis, which will progress to cirrhosis and HCC.4,5 Hepatic resection, liver transplantation, chemotherapy, targeted drugs, and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are the current treatment modalities for the treatment of MAFLD-related HCC.6 Multivariate analysis showed that lenvatinib, as the first-line treatment, can improve the survival of HCC patients,7 while most patients are not responsive to recently Food and Drug Administration-approved immune checkpoint therapies.8 Given that immune suppression disorders and alterations in the liver microenvironment are the main pathological manifestations of MAFLD-HCC, understanding the mechanisms regulating these processes will lead to the identification of strategies against this deadly disease.

肝细胞癌(HCC)是全球第六大常见癌症,主要归因于乙型肝炎病毒(HBV)和丙型肝炎病毒(HCV)感染的高流行率,以及近年来代谢功能障碍相关脂肪性肝病(MAFLD)的日益增多。MAFLD 作为一种备受关注的疾病,其患病率持续攀升;30%的成年人口和 80%的肥胖人群受此疾病影响,使其成为发达国家最常见的慢性肝病。2020 年,国际专家小组发表声明建议用非酒精性脂肪性肝病(NAFLD)替代 MAFLD 这一命名。该疾病的肝脏病理谱系从单纯性脂肪变(仅表现为肝细胞内过量脂肪沉积)延伸至非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(NASH),后者还伴有肝细胞损伤、肝脏炎症及细胞周围纤维化等特征,最终将进展为肝硬化和 HCC。目前针对 MAFLD 相关 HCC 的治疗手段包括肝切除术、肝移植、化疗、靶向药物及免疫检查点抑制剂(ICIs)。 多变量分析显示,仑伐替尼作为一线治疗可改善肝细胞癌患者生存率,而多数患者对近期美国食品药品监督管理局批准的免疫检查点疗法无应答。鉴于免疫抑制紊乱和肝脏微环境改变是 MAFLD 相关肝癌的主要病理表现,阐明这些过程的调控机制将有助于制定对抗这一致命疾病的策略。

Exciting advances in research have shown that gut-liver communication contributes to MAFLD progression.9 The most typical characteristics of MAFLD progression include a decrease in microbiota diversity and changes in the ratio of gram-negative bacteria to gram-positive counterparts.10 Functionally, MAFLD progresses via a shift from beneficial to harmful microbiota in guts, leading to the development of a proinflammatory and metabolically toxic environment via modulation of intestinal integrity.11 Probiotic administration attenuated MAFLD progression in mouse models and clinical patients.12 However, how the gut microbiota is altered in the process of MAFLD-HCC remains elusive. Multiple studies have indicated the involvement of gut microbiota in gastrointestinal cancers.13,14,15 Specifically, others have reported that gut microbiota alteration is associated with MAFLD and subsequent progression to HCC.16 As the gut microbiota plays a critical role in regulating immune homeostasis, it is important to identify a key microbiota that not only can suppress MAFLD-HCC but also, most importantly, complements ICI treatment.

令人振奋的研究进展表明,肠-肝轴通讯促进了代谢相关脂肪性肝病(MAFLD)的进展。 9 MAFLD 进展最典型的特征包括微生物群多样性下降以及革兰氏阴性菌与革兰氏阳性菌比例的变化。 10 从功能角度看,MAFLD 通过肠道菌群从有益菌向有害菌的转变而进展,这种转变通过调节肠道完整性导致促炎和代谢毒性环境的形成。 11 益生菌给药在小鼠模型和临床患者中均能缓解 MAFLD 进展。 12 然而,MAFLD-HCC 发展过程中肠道菌群如何改变仍不清楚。多项研究表明肠道菌群参与胃肠道癌症的发生。 13 14 15 特别值得注意的是,已有报道指出肠道菌群改变与 MAFLD 及其向 HCC 的后续进展相关。 16 鉴于肠道菌群在调节免疫稳态中起关键作用,鉴定出一种既能抑制 MAFLD-HCC 发展,更重要的是又能增强免疫检查点抑制剂(ICI)治疗效果的关键菌群具有重要意义。

With our established MAFLD-promoted mouse HCC model, coupled with 16S rRNA sequencing analysis, we identified that Akkermansia muciniphila (Akk) decreased from healthy to HCC tissues in a stepwise manner. Interestingly, we found that daily administration of Akk could effectively attenuate the development of steatosis and tumor growth in MAFLD-HCC mouse models. Consistent with the physiological function of Akk in the maintenance of intestinal integrity, we found that Akk repaired the intestinal lining, accompanied by a decrease in the serum concentration of LPS and bile acid metabolites. Using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and immunoprofiling analyses, we found that Akk decreased the populations of immunosuppressive cells, including monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (m-MDSCs) and M2 macrophages, which may lead to T cell infiltration and activation. Daily Akk administration, in combination with PD1 treatment, exerts the maximal growth-suppressive effect by favoring T cell function in multiple MAFLD-HCC mouse models. Clinically, Akk may serve as a biomarker for the prediction of the PD1 response in HCC patients.

通过我们建立的 MAFLD 促进小鼠 HCC 模型,结合 16S rRNA 测序分析,我们发现 Akkermansia muciniphila(Akk)从健康组织到 HCC 组织呈逐步减少趋势。值得注意的是,每日补充 Akk 能有效缓解 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型的脂肪变性和肿瘤生长。与 Akk 维持肠道完整性的生理功能一致,我们发现 Akk 修复了肠道屏障,同时伴随血清 LPS 和胆汁酸代谢物浓度下降。通过单细胞 RNA 测序(scRNA-seq)和免疫特征分析,我们发现 Akk 减少了免疫抑制细胞群,包括单核髓系来源的抑制性细胞(m-MDSCs)和 M2 型巨噬细胞,这可能促进 T 细胞浸润和活化。在多种 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型中,每日 Akk 补充联合 PD1 治疗通过增强 T 细胞功能产生了最大化的生长抑制效果。临床意义上,Akk 或可作为预测 HCC 患者 PD1 治疗反应的生物标志物。

Results 结果

Akk is identified in the MAFLD-promoted HCC mouse model

在 MAFLD 促进的 HCC 小鼠模型中鉴定出 Akk 菌

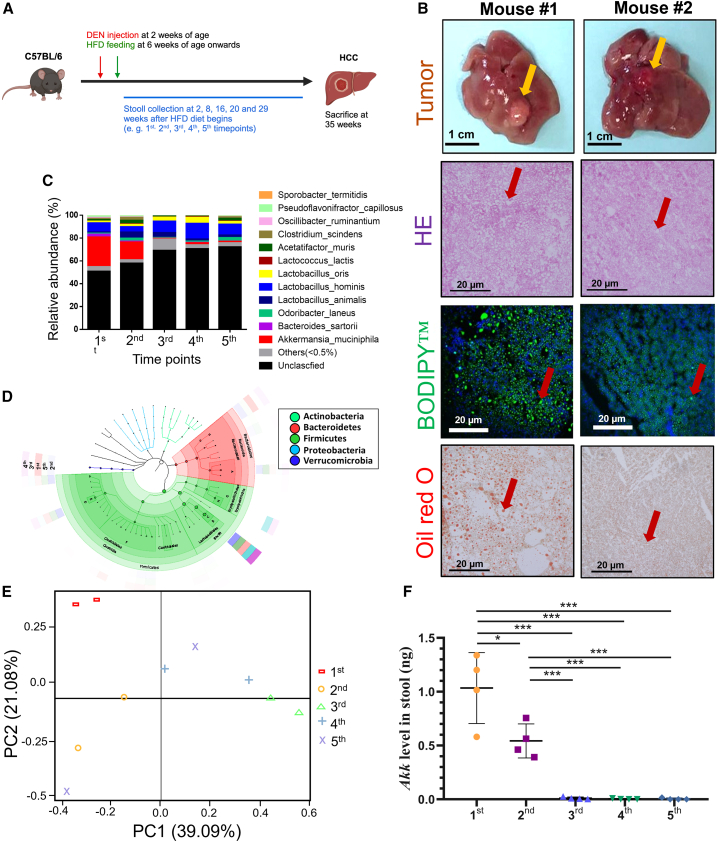

Recent reports have shown that gut microbiota alteration is associated with MAFLD and HCC progression.9 However, how the gut microbiota is altered during the development of MAFLD-HCC remains unknown. Therefore, we established an MAFLD-promoted HCC mouse model, where the mouse develops HCC in 35 weeks upon injection of diethylnitrosamine (DEN) and a high-fat diet (HFD)17 (Figure 1A). H&E staining revealed the hepatocellular ballooning of the NASH background and histopathology of HCC tumors (Figure 1B). Additionally, BODIPY and oil red O staining demonstrated the accumulation of numerous hepatic lipids upon HFD feeding (Figure 1B). During the HCC tumor development, we collected feces at five different time points and extracted corresponding fecal DNA for 16S rRNA sequencing analysis. The relative abundance of dominant genera was compared. Genera with abundance ≥0.5% were bar plotted. We found that Akk decreased approximately 40-fold from healthy to HCC in a time-dependent manner (Figures 1C and 1D). Principal coordinates analysis of the 16S amplicon data using a two-dimensional principal-component analysis (2D-PCA) plot of the experimental group displayed a wide separation among different time points (Figure 1E). qPCR analysis confirmed this observation, in which the levels of Akk were decreased across the experimental time points during the HCC development (Figure 1F). To determine whether age plays a role in the decrease of Akk levels, we examined the Akk levels in fecal samples from control mice fed a normal diet at the same time point as the MAFLD-promoted HCC mouse model using qPCR analysis (Figure S1A). Our results showed that there is no significant difference in Akk levels across the same five time points as HFD diet (Figure S1B), further confirming that the reduction in Akk is associated with the development of MAFLD-HCC.

近期研究表明,肠道菌群改变与代谢相关脂肪性肝病(MAFLD)和肝细胞癌(HCC)进展相关。然而,MAFLD-HCC 发展过程中肠道菌群如何变化尚不明确。为此,我们建立了 MAFLD 促进的 HCC 小鼠模型,通过注射二乙基亚硝胺(DEN)联合高脂饮食(HFD)喂养 35 周诱导小鼠发生 HCC(图 A)。H&E 染色显示非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(NASH)背景下的肝细胞气球样变及 HCC 肿瘤组织病理学特征(图 B)。BODIPY 和油红 O 染色进一步证实 HFD 喂养导致大量肝脏脂质蓄积(图 B)。在 HCC 肿瘤发展过程中,我们在五个不同时间点采集粪便样本并提取相应粪便 DNA 进行 16S rRNA 测序分析。比较优势菌属相对丰度后,将丰度≥0.5%的菌属绘制柱状图。研究发现,从健康状态到 HCC 阶段,阿克曼菌(Akk)丰度呈现时间依赖性下降,降幅约达 40 倍(图 C 和 1D)。 基于 16S 扩增子数据的主坐标分析显示,实验组二维主成分分析(2D-PCA)图中不同时间点呈现明显分离趋势(图 6E)。qPCR 分析验证了这一发现,在肝癌发展过程中,Akk 菌水平随实验时间点推移持续下降(图 7F)。为探究年龄因素是否影响 Akk 水平下降,我们通过 qPCR 检测了正常饮食对照组小鼠在与 MAFLD 诱发肝癌模型相同时间点的粪便样本中 Akk 水平(图 8A)。结果显示,与高脂饮食组相同的五个时间点间 Akk 水平无显著差异(图 9B),进一步证实 Akk 减少与 MAFLD-HCC 发展进程相关。

Figure 1. 图 1.

Decrease in the level of Akk in the MAFLD-promoted HCC mouse model

MAFLD 促进的 HCC 小鼠模型中 Akk 水平下降

(A) HFD-fed mice were followed through the experiment. Time point for stool collection: HFD feeding after (1st) 2 weeks, (2nd) 8 weeks, (3rd) 16 weeks, (4th) 20 weeks, and (5th) 29 weeks.

(A) 实验全程监测高脂饮食喂养小鼠。粪便采集时间点分别为:高脂饮食喂养后(1 st )2 周、(2 nd )8 周、(3 rd )16 周、(4 th )20 周及(5 th )29 周。

(B) Tumor formation was observed at 35 weeks (yellow arrowheads indicate tumor nodules). Representative images of H&E, BODIPY, and oil red O staining at the endpoint are shown. BODIPY staining (green) and DAPI staining (blue). Red arrowheads denote ballooning features and fat deposition. Scale bar, 1 cm for the liver. Scale bar, 20 μm for H&E and IF.

(B) 第 35 周观察到肿瘤形成(黄色箭头指示肿瘤结节)。终点时 H&E 染色、BODIPY 染色和油红 O 染色的代表性图像如图所示。BODIPY 染色(绿色)与 DAPI 染色(蓝色)。红色箭头标示气球样变特征及脂肪沉积。肝脏比例尺为 1 厘米,H&E 和免疫荧光染色比例尺为 20 微米。

(C) Species-level 16S rRNA sequencing results showing the relative abundance (%) of the intestinal bacterial composition of the mice fed HFD.

(C) 物种水平 16S rRNA 测序结果显示高脂饮食喂养小鼠肠道菌群组成的相对丰度(%)。

(D) Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and taxonomic cladograms show differentially abundant taxa among five different time points.

(D) 线性判别分析(LDA)与分类学分支图展示五个不同时间点间差异显著的菌群分类单元。

(E) Compositional variation at five different time points.

(E) 五个不同时间点的组成变化。

(F) qPCR analysis showed a decrease in Akk levels in a time-dependent manner (n = 4).

(F) qPCR 分析显示 Akk 水平呈时间依赖性下降(n = 4)。

Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each spot representing one subject. Statistical significance was assessed by two-sided Student’s t test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. See also Figure S1 and Table S3.

数据以均值±标准差表示,每个数据点代表一个受试对象。统计学显著性采用双尾 Student t 检验评估。∗p < 0.05,∗∗∗p < 0.001。另见 Figure S1 和 Table S3 。

Akk ameliorates tumor progression in MAFLD-HCC mouse models

Akk 菌可改善 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型的肿瘤进展

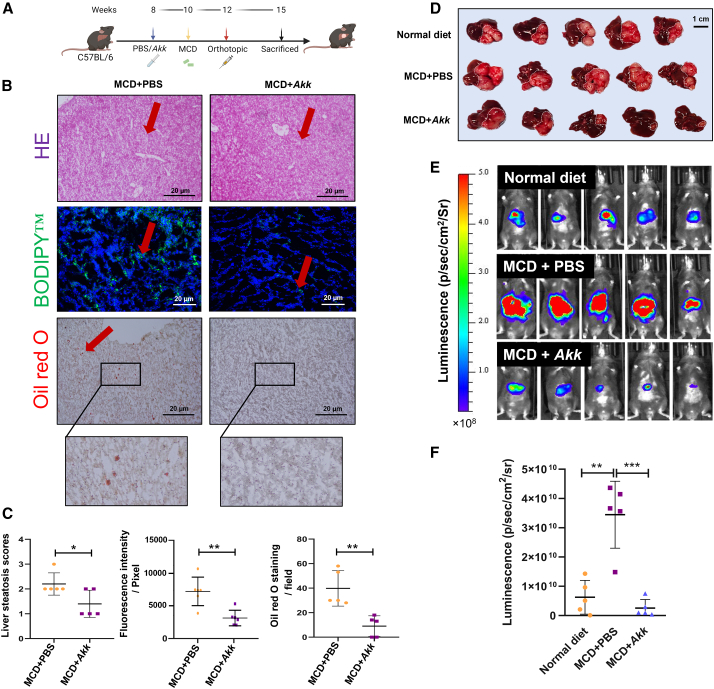

Based on this interesting finding, we proceeded with animal testing to examine whether supplementation with Akk can reverse tumor growth in an orthotopic MAFLD-HCC mouse model. For this purpose, we fed the mice with a methionine- and choline-deficient (MCD) diet, followed by orthotopic implantation of luciferase-labeled RIL-175 cells (Figure 2A).18 The successful establishment of steatotic livers was confirmed through H&E, BODIPY, and oil red O staining. Notably, the severity of steatosis was reduced following Akk treatment (Figures 2B and 2C). To assess tumor progression, we utilized bioluminescence imaging (BLI) to track tumor development upon tumor inoculation at day 6 and day 12 (Figure S2). In day 20 with the luciferase signal, larger tumors were found in the MCD-treated groups than in mice fed a normal diet, suggesting a tumor-promoting capacity in the NASH background (Figures 2D–2F). Akk-treated group exhibited the smallest tumor burden when compared with the other two groups. To examine whether Akk retards tumor growth by suppressing the proliferation of HCC cells, we examined the expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) between the PBS-control and Akk-treated groups of MCD diet. We observed a significant suppression of HCC tumor proliferation upon Akk treatment (Figure S3). In a separate MAFLD-HCC model, we administered Akk to mice on a high-fat, high-cholesterol (HFHC) diet for more than 8 months (Figure S4A). Compared to control group, Akk-treated mice exhibited a trend toward decreased tumor burden, as evidenced by reduced liver weight (p = 0.0592) (Figure S4B), which was associated with reduced liver steatosis (Figure S4C). Moreover, qPCR analysis confirmed that the levels of Akk were decreased across the experimental time points with the MAFLD development (Figure S4D). Overall, our results indicate that Akk treatment can slow down the development of MAFLD into HCC.

基于这一有趣发现,我们随即开展动物实验,探究补充 Akk 菌能否逆转原位 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型的肿瘤生长。为此,我们给小鼠喂食缺乏蛋氨酸和胆碱(MCD)的饲料,随后原位植入荧光素酶标记的 RIL-175 细胞(图 0A)。通过 H&E 染色、BODIPY 染色和油红 O 染色证实了脂肪肝模型的成功建立。值得注意的是,Akk 治疗组肝脏脂肪变性程度显著减轻(图 2B 和 2C)。为评估肿瘤进展,我们在接种后第 6 天和第 12 天采用生物发光成像(BLI)技术追踪肿瘤发展情况(图 3)。第 20 天荧光信号显示,MCD 饲料组比正常饮食组出现更大肿瘤,表明 NASH 微环境具有促肿瘤特性(图 4D-2F)。与其他两组相比,Akk 治疗组表现出最小的肿瘤负荷。 为探究 Akk 是否通过抑制肝癌细胞增殖来延缓肿瘤生长,我们检测了 MCD 饮食组中 PBS 对照组与 Akk 治疗组的增殖细胞核抗原(PCNA)表达水平。结果显示 Akk 治疗能显著抑制肝癌肿瘤增殖(图 5)。在另一项 MAFLD-HCC 模型中,我们对高脂高胆固醇(HFHC)饮食喂养超过 8 个月的小鼠给予 Akk 干预(图 6A)。与对照组相比,Akk 治疗组小鼠表现出肿瘤负荷降低趋势,肝脏重量减轻(p=0.0592)证实了这一结果(图 7B),且与肝脏脂肪变性程度减轻相关(图 8C)。此外,qPCR 分析证实随着 MAFLD 病程发展,各时间点 Akk 水平均呈下降趋势(图 9D)。综上,我们的研究结果表明 Akk 治疗可延缓 MAFLD 向 HCC 的进展。

Figure 2. 图 2.

The effect of Akk administration on tumor formation in an orthotopic MAFLD-HCC mouse model

Akk 菌给药对原位 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型肿瘤形成的影响

(A) Experimental schedule for characterizing the role of Akk in the orthotopic MAFLD-HCC mouse model.

(A) 用于表征 Akk 在 MAFLD-HCC 原位小鼠模型中作用的实验流程示意图。

(B) Representative images of H&E, BODIPY, and oil red O staining at the endpoint are shown. Red arrowheads denote ballooning features and fat deposition. Scale bar, 20 μm.

(B) 终点时 H&E、BODIPY 和油红 O 染色的代表性图像如图所示。红色箭头指示气球样变特征及脂肪沉积。比例尺为 20 微米。

(C) Liver steatosis scores of liver sections, fluorescence intensity of BODIPY, and oil red O staining counts were shown in PBS- and Akk-treated mice fed with MCD diet (n = 5).

(C) 采用 MCD 饮食喂养的小鼠经 PBS 和 Akk 处理后,肝脏切片的脂肪变性评分、BODIPY 荧光强度及油红 O 染色计数结果展示(n=5)。

(D) Representative images of MAFLD-HCC tumors generated with an MCD diet and orthotopic implantation of RIL-175 HCC cells following treatment with a normal diet with PBS (normal + PBS, n = 5), an MCD diet with PBS (MCD + PBS, n = 5), and an MCD diet with Akk (MCD + Akk, n = 5); scale bar, 1 cm. Dotted lines indicate tumor regions.

(D) 代表性 MAFLD-HCC 肿瘤图像:通过 MCD 饮食联合 RIL-175 肝癌细胞原位移植构建模型,分别显示正常饮食+PBS 组(normal + PBS,n=5)、MCD 饮食+PBS 组(MCD + PBS,n=5)及 MCD 饮食+Akk 组(MCD + Akk,n=5)处理后的肿瘤形态;比例尺为 1 厘米。虚线标示肿瘤区域。

(E) Bioluminescent imaging for luciferase activity in the PBS (normal + PBS, n = 5), an MCD diet with PBS (MCD + PBS, n = 5), and an MCD diet with Akk (MCD + Akk, n = 5) treatment groups on day 20 upon post-orthotopic transplantation.

(E) 原位移植后第 20 天,PBS 组(normal + PBS,n=5)、MCD 饮食+PBS 组(MCD + PBS,n=5)及 MCD 饮食+Akk 组(MCD + Akk,n=5)处理组的荧光素酶活性生物发光成像结果。

(F) The dot plot shows the total flux of luciferase signal captured by in vivo image system (IVIS) in each group on day 20 upon post-orthotopic transplantation (n = 5).

(F) 点状图显示原位移植术后第 20 天各组活体成像系统(IVIS)捕获的荧光素酶信号总通量(n = 5)。

Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each spot representing one subject. Statistical significance was assessed by two-sided Student’s t test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. See also Figures S2–S4.

数据以均值±标准差表示,每个点代表一个受试对象。统计学显著性采用双尾 Student t 检验评估。∗p < 0.05,∗∗p < 0.01,∗∗∗p < 0.001。另见 Figures S2–S4 。

Akk alleviates hepatic steatosis by suppressing cholesterol biosynthesis and bile acid metabolism

Akk 通过抑制胆固醇生物合成和胆汁酸代谢缓解肝脏脂肪变性

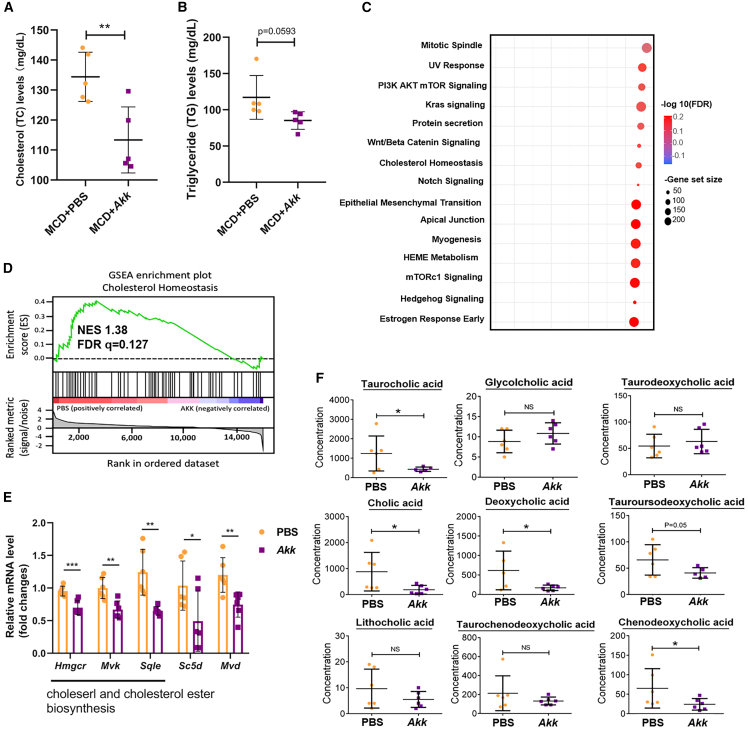

Given that serum total cholesterol (TC) and triglyceride (TG) are positively correlated with liver steatosis, we further examined whether supplementation with Akk would result in alterations of these two serum proteins in an orthotopic MAFLD-HCC mouse model fed with MCD diet. Upon analysis, Akk was further demonstrated to alleviate liver steatosis, as evidenced by a marked decrease in serum TC and TG levels (Figures 3A and 3B). Similar findings were observed in an MAFLD-HCC mouse model fed with HFHC (Figures S4E and S4F). To further examine the mechanism underlying the negative regulatory role of Akk in hepatic steatosis, we performed bulk RNA sequencing to compare the genetic alterations between the Akk-treated and PBS-control groups. Over 90% (41/50) of hallmark gene sets were upregulated in the control group, while 15 gene sets were significant at a false discovery rate (FDR) <25%. Less than 20% (9/50) of hallmark gene sets were upregulated in the Akk group, while only 3 gene sets were significant. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) demonstrated that Akk downregulated pathways were related to cholesterol homeostasis, Wnt/β-catenin, PI3/Akt mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling, etc. (Figure 3C). We focused on the effect of Akk on cholesterol biosynthesis (Figure 3D), as previous reports showed the role of cholesterol biosynthesis in the promotion of steatohepatitis-related HCC.19,20 We analyzed the genes related to cholesterol homeostasis between the Akk-treated and PBS-control groups. Most cholesterol homeostasis-related genes were differentially expressed in Akk-treated and PBS-control groups. Consistent with this finding, several genes related to cholesterol biosynthesis were found to be significantly downregulated (Figure 3E). Bile acid synthesis is a major pathway for hepatic cholesterol catabolism,21 and its metabolites significantly contribute to the development of steatosis.22 Likewise, the Akk-treated group showed a significant decrease in the number of bile acid metabolites, including taurocholic acid, cholic acid, deoxycholic acid, tauroursodeoxycholic acid, and chenodeoxycholic acid (Figure 3F). Taken together, these results indicate that Akk administration ameliorates hepatic steatosis possibly via the suppression of cholesterol biosynthesis.

鉴于血清总胆固醇(TC)和甘油三酯(TG)与肝脏脂肪变性呈正相关,我们进一步研究了在 MCD 饮食诱导的 MAFLD-HCC 原位小鼠模型中补充 Akk 是否会导致这两种血清蛋白水平变化。分析显示,Akk 能显著降低血清 TC 和 TG 水平(图 0#A 和 3B),证实其可缓解肝脏脂肪变性。在 HFHC 饮食诱导的 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型中也观察到类似结果(图 1#E 和 S4F)。为深入探究 Akk 抑制肝脏脂肪变性的分子机制,我们通过批量 RNA 测序比较了 Akk 处理组与 PBS 对照组间的基因表达差异。对照组中超过 90%(41/50)的标志性基因集表达上调,其中 15 个基因集在错误发现率(FDR)<25%时具有统计学意义;而 Akk 组仅不到 20%(9/50)的标志性基因集表达上调,其中仅 3 个基因集达到显著水平。 基因集富集分析(GSEA)显示,Akk 菌下调的通路与胆固醇稳态、Wnt/β-连环蛋白、PI3/Akt mTOR(哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白)信号传导等相关(图 2C)。我们重点关注 Akk 菌对胆固醇生物合成的影响(图 3D),因既往研究表明胆固醇生物合成在促进脂肪性肝炎相关肝癌中起关键作用。通过对比 Akk 菌处理组与 PBS 对照组,我们发现两组间多数胆固醇稳态相关基因存在差异表达。与此一致的是,若干胆固醇生物合成相关基因呈现显著下调(图 6E)。胆汁酸合成是肝脏胆固醇分解代谢的主要途径,其代谢产物对脂肪变性发展具有重要影响。同样,Akk 菌处理组中胆汁酸代谢物(包括牛磺胆酸、胆酸、脱氧胆酸、牛磺熊去氧胆酸和鹅去氧胆酸)数量显著减少(图 9F)。 综上所述,这些结果表明 Akk 菌的施用可能通过抑制胆固醇生物合成来改善肝脏脂肪变性。

Figure 3. 图 3.

The effect of Akk administration on hepatic steatosis, cholesterol biosynthesis, and bile acid metabolism

阿克曼菌给药对肝脏脂肪变性、胆固醇生物合成和胆汁酸代谢的影响

(A and B) (A) Serum TC and (B) TG levels in PBS (n = 5) and Akk (n = 5) groups were shown.

(A 和 B) (A)展示了 PBS 组(n=5)与 Akk 组(n=5)的血清总胆固醇(TC)水平;(B)展示了两组的甘油三酯(TG)水平。

(C) GO analysis revealed enrichment of several cellular pathways in the control PBS group compared with the Akk-treated groups.

(C) GO 分析显示,与 Akk 处理组相比,PBS 对照组中多个细胞通路呈现富集现象。

(D) GSEA showed the enrichment of cholesterol homeostasis in the control PBS group.

(D) GSEA 分析表明胆固醇稳态通路在 PBS 对照组中显著富集。

(E) By qPCR analysis, the expression of genes related to cholesterol homeostasis, including Hmgcr, Mvk, Sqle, Sc5d, and Mvd, was examined in the Akk-treated and PBS-control groups.

(E) 通过 qPCR 检测发现,Akk 处理组与 PBS 对照组中胆固醇稳态相关基因(Hmgcr、Mvk、Sqle、Sc5d 和 Mvd)的表达存在差异。

(F) Serum bile acid metabolomics panels between Akk-treated (n = 5) and PBS-control groups (n = 5) were compared by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry.

通过液相色谱-质谱法比较了 Akk 处理组(n=5)与 PBS 对照组(n=5)之间的血清胆汁酸代谢组学特征。

Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each spot representing one subject. Statistical significance was assessed by two-sided Student’s t test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. NS, not significant. See also Figure S5.

数据以均值±标准差表示,每个点代表一个受试对象。统计学显著性采用双尾 Student t 检验评估。∗p < 0.05,∗∗p < 0.01,∗∗∗p < 0.001。NS 表示无统计学意义。另见 Figure S5 。

Akk improves intestinal membrane integrity

Akk 菌可改善肠道黏膜完整性

Akk is a strictly anaerobic and mucin-degrading bacterium that colonizes the gut of humans and rodents. Akk is highly abundant (1%–5%) in the outer mucus layer near the intestinal lining of the gut.23

Akk functions to maintain and strengthen the integrity of the gut lining. Given the physiological function of Akk in the intestine, we believe that a decrease in Akk may lead to impairment of the intestinal lining. Consistently, we found that Akk repaired the intestinal lining, as evidenced by the increased expression of tight junction proteins, including ZO-1, Occludin, and Claudins 1 and 4, in colonic tissues upon treatment with Akk (Figures S5A–S5E). Upon improvement of intestinal membrane integrity, we believe that an increase in Akk may lead to improvement of the intestinal lining, which subsequently decreases the flux of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Consistently, LPS was downregulated in the serum of Akk-treated mice in an MAFLD-HCC model fed with HFHC diet (Figure S4G) and an orthotopic MAFLD-HCC mouse model fed with MCD diet (Figure S5F).

阿克曼菌(Akk)是一种严格厌氧且能降解黏蛋白的细菌,定植于人类和啮齿动物的肠道中。该菌在肠道黏膜外层含量丰富(1%-5%),其功能是维持并增强肠道黏膜屏障的完整性。鉴于阿克曼菌在肠道中的生理功能,我们认为其数量减少可能导致肠道黏膜损伤。实验证实,经阿克曼菌处理后,结肠组织中紧密连接蛋白(包括 ZO-1、Occludin 以及 Claudin 1 和 4)的表达增加,表明该菌具有修复肠道黏膜的作用(图 1A-S5E)。随着肠道黏膜完整性的改善,我们认为阿克曼菌数量增加可能改善肠道屏障功能,从而降低脂多糖(LPS)的渗透。在喂食高脂高胆固醇(HFHC)饮食的 MAFLD-HCC 模型中(图 2G)及喂食蛋氨酸胆碱缺乏(MCD)饮食的原位 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型中(图 3F),阿克曼菌处理组小鼠血清中的 LPS 水平均出现下调。

m-MDSCs and M2 macrophages are decreased in tumors of Akk-treated mice

阿克曼氏菌处理小鼠的肿瘤中 m-MDSCs 和 M2 巨噬细胞数量减少

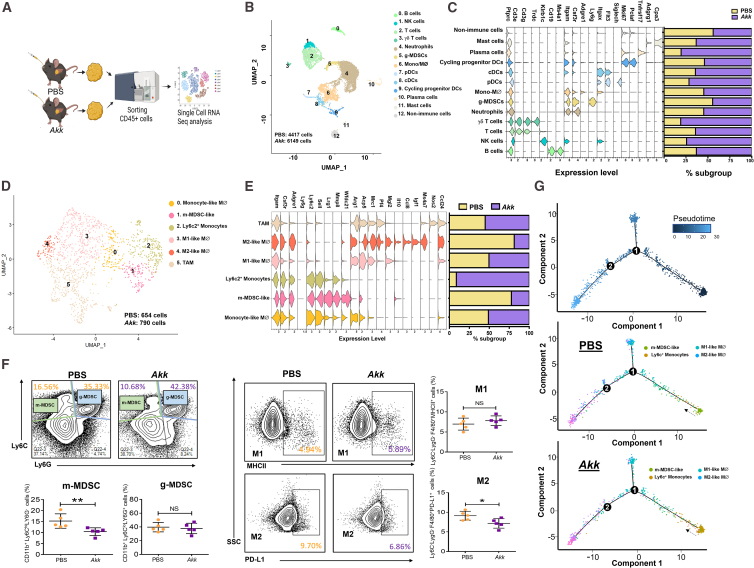

Based on Figures S4G and S5F, we examined the effect of Akk on the regulation of innate immunity in the tumor microenvironment, as LPS is regarded as an important regulator of innate immune cells. We extracted CD45+ cells from tumors treated with either Akk or PBS and analyzed them by using scRNA-seq (Figure 4A). The uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot, generated with scRNA-seq data, shows different immune cell clusters based on their marker expression (Figure 4B). In general, we observed increased populations of mast cells, plasma cells, dendritic cells (DCs), T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and B cells in the Akk-treated group (Figure 4C). Secondary clusters were identified as Mo/Macs, m-MDSCs, M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages, and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) (Figure 4D). Interestingly, we found that the total populations of m-MDSCs and M2 macrophages were decreased, while total Ly6c2-high immature monocytes (“Ly6c2+monocytes”) were increased in the Akk-treated groups (Figure 4E). Consistently, immunoprofiling analysis found a significant decrease in m-MDSCs and M2 macrophages in Akk-treated tumors (Figure 4F). To further understand how Akk regulates the populations of m-MDSCs and M2 macrophages, we performed velocity analysis, which revealed the transcriptional dynamics of m-MDSCs and M2 macrophages. RNA velocity predicted that the differentiation and polarization of the M2 subpopulation from Ly6c+monocytes and m-MDSCs in tumors of the PBS group were increased. The polarization of M2 macrophages from Ly6c+monocytes in tumors of the Akk-treated group was suppressed (Figure 4G). To further clarify these cellular changes, we first elucidated the pathway that was altered in m-MDSCs upon Akk treatment. By GSEA analysis using the same set of scRNA-seq data, we found suppression of the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway with consistent suppression of NF-κB genes, which was further confirmed by qPCR analysis (Figures S6A and S6B). Notably, TLR2, a critical receptor of LPS, was found to be downregulated (Figure S6C). As TLR2-NF-κB activation was previously reported to play a crucial role in m-MDSC expansion,24,25,26 we reasoned that Akk suppressed the expansion of m-MDSCs by blocking the influx of LPS to the liver via the intestinal membrane. Consistently, we found a significant decrease in the population of TLR2+ MDSCs, as evidenced by multiplexed immunofluorescence (IF) staining (Figure S6D). To further understand how Akk regulates the populations of these innate immune cells and, lastly, to further validate the function of m-MDSCs in M2 macrophage polarization, we performed a co-culture system in which mouse macrophage cell line (Raw264.7) was co-incubated with m-MDSCs in either PBS- or Akk-treated groups and found that m-MDSCs in Akk-treated groups significantly suppressed M2 polarization compared to the control group (Figure S6E). To confirm the role of LPS influx through the intestinal barrier in the regulation of m-MDSCs and M2 macrophages by Akk, we employed a mouse model of colitis, in which the intestinal barrier is compromised by giving 2% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) for a week (Figure S7A). This model was successfully established as evidenced by H&E (Figure S7B) and Alcian blue staining (Figure S7C), which was accompanied by a substantial decrease in body weight (Figure S7D). Consistently, Akk mitigated the damaging effects of 2% DSS on intestinal membrane integrity and significantly reduced LPS detection (Figure S7E) and accompanied with decrease in m-MDSCs (Figures S7F and S7G) and M2 macrophages detection (Figures S7H and S7I). This finding further provides a mechanistic insight of how Akk regulates the populations of these innate immune cells.

基于 Figures S4 G 和 S5 F 的研究,我们考察了 Akk 对肿瘤微环境先天免疫调节的影响,因为 LPS 被认为是先天免疫细胞的重要调节因子。我们从经 Akk 或 PBS 处理的肿瘤中提取 CD45 + 细胞,并采用单细胞 RNA 测序(scRNA-seq)进行分析( Figure 4 A)。通过 scRNA-seq 数据生成的均匀流形近似与投影(UMAP)图谱显示,基于标记物表达的不同免疫细胞群存在差异( Figure 4 B)。总体而言,我们观察到 Akk 处理组中肥大细胞、浆细胞、树突状细胞(DCs)、T 细胞、自然杀伤(NK)细胞和 B 细胞数量增加( Figure 4 C)。次级细胞群被鉴定为单核/巨噬细胞(Mo/Macs)、髓系来源的抑制性细胞(m-MDSCs)、M1 型巨噬细胞、M2 型巨噬细胞和肿瘤相关巨噬细胞(TAMs)( Figure 4 D)。值得注意的是,Akk 处理组中 m-MDSCs 和 M2 型巨噬细胞总量减少,而 Ly6c2 高表达的不成熟单核细胞("Ly6c2 + 单核细胞")总量增加( Figure 4 E)。免疫谱分析一致显示,经 Akk 处理的肿瘤中 m-MDSCs 和 M2 型巨噬细胞显著减少( Figure 4 F)。 为深入探究 Akk 如何调控 m-MDSCs 和 M2 巨噬细胞群体,我们进行了速率分析,揭示了这两种细胞的转录动态特征。RNA 速率预测显示:PBS 组肿瘤中 Ly6c + 单核细胞向 M2 亚群的分化极化及 m-MDSCs 的 M2 极化程度增强;而 Akk 治疗组肿瘤中 Ly6c + 单核细胞向 M2 巨噬细胞的极化过程受到抑制( Figure 4 G)。为进一步阐明这些细胞变化,我们首先解析了 Akk 干预后 m-MDSCs 中发生改变的信号通路。通过同一单细胞 RNA 测序数据的 GSEA 分析,发现核因子κB(NF-κB)通路及其相关基因表达均受到抑制,qPCR 分析进一步验证了这一结果( Figures S6 A 和 S6B)。值得注意的是,LPS 的关键受体 TLR2 表达水平下调( Figure S6 C)。鉴于既往研究报道 TLR2-NF-κB 激活对 m-MDSCs 扩增具有关键作用 24 25 26 ,我们推测 Akk 可能通过阻断 LPS 经肠黏膜向肝脏的迁移,从而抑制 m-MDSCs 的扩增。 我们通过多重免疫荧光(IF)染色( Figure S6 D)证实,TLR2 + MDSCs 细胞群数量显著减少。为进一步探究 Akk 如何调控这些先天免疫细胞群,并最终验证 m-MDSCs 在 M2 型巨噬细胞极化中的作用,我们建立了共培养体系:将小鼠巨噬细胞系(Raw264.7)分别与 PBS 组或 Akk 处理组的 m-MDSCs 共孵育,发现相较于对照组,Akk 处理组的 m-MDSCs 显著抑制了 M2 极化( Figure S6 E)。为验证 Akk 通过肠道屏障的 LPS 内流调控 m-MDSCs 和 M2 巨噬细胞的作用机制,我们采用结肠炎小鼠模型(通过给予 2%葡聚糖硫酸钠(DSS)一周破坏肠道屏障)( Figure S7 A)。H&E( Figure S7 B)和阿利新蓝染色( Figure S7 C)显示模型构建成功,同时伴随体重显著下降( Figure S7 D)。 与之一致的是,Akk 减轻了 2% DSS 对肠道黏膜完整性的破坏作用,并显著降低了 LPS 检测水平(图 25E),同时伴随 m-MDSCs(图 26F 和 S7G)与 M2 型巨噬细胞(图 27H 和 S7I)数量的减少。该发现进一步从机制层面揭示了 Akk 如何调控这些先天免疫细胞群。

Figure 4. 图 4.

The effect of Akk administration on m-MDSCs and M2 macrophages in tumors in an orthotopic MAFLD-HCC mouse model

在 MAFLD-HCC 原位小鼠模型中,Akk 给药对肿瘤内 m-MDSCs 和 M2 巨噬细胞的影响

(A) Schematic diagram showing the workflow of the isolation of CD45+ cells from HCC tumors treated with either PBS-control group (n = 5) or Akk-treated group (n = 7) for scRNA-seq analysis.

(A) 流程图展示从 PBS 对照组(n=5)或 Akk 处理组(n=7)的 HCC 肿瘤中分离 CD45 + 细胞进行单细胞 RNA 测序分析的工作流程

(B) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot showing 12 distinct clusters resulting from scRNA-seq of sorted CD45+ cells derived from tumors harvested from PBS- and Akk-treated group.

(B) 均匀流形近似与投影(UMAP)图显示经 PBS 组和 Akk 组处理的肿瘤来源 CD45 + 细胞单细胞测序后形成的 12 个不同细胞簇

(C) Violin plot displayed the marker genes for each immune cell cluster. The percentage of major immune cell types in PBS- or Akk-treated group was calculated and shown as bar plot. Higher percentage of cells present in the subpopulation of mast cells, plasma cells, DCs, T cells, NK cells, and B cells were observed in the Akk-treated group.

(C) 小提琴图展示各免疫细胞簇的标志基因。柱状图显示 PBS 组与 Akk 组主要免疫细胞类型占比。Akk 处理组中肥大细胞、浆细胞、树突状细胞、T 细胞、NK 细胞和 B 细胞亚群比例更高

(D) UMAP plot demonstrating secondary clusters obtained from two biological groups and identified as monocytic like macrophages, Ly6c2+ monocytes, m-MDSCs, M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages, and TAMs.

(D) UMAP 图展示两个生物处理组获得的次级细胞簇,鉴定为单核样巨噬细胞、Ly6c2 + 单核细胞、m-MDSCs、M1 型巨噬细胞、M2 型巨噬细胞和肿瘤相关巨噬细胞(TAMs)

(E) Violin plot displayed the marker genes for each immune cell cluster. Bar plot showing the alterations in subsets of cell populations in response to the indicated treatments.

(E) 小提琴图展示各免疫细胞簇的标志基因。条形图显示指定处理后细胞亚群比例的变化。

(F) Representative flow cytometry plots of m-MDSCs (left) and g-MDSCs (right) in the PBS- and Akk-treated groups (n = 5). Representative flow cytometry plots of M1 macrophages (F4/80+MHCII+) and M2 macrophages (F4/80+PD-L1+) in the PBS- and Akk-treated groups (n = 5).

(F) PBS 处理组与 Akk 处理组中 m-MDSCs(左)和 g-MDSCs(右)的代表性流式细胞图(n=5)。PBS 处理组与 Akk 处理组中 M1 巨噬细胞(F4/80 + MHCII + )和 M2 巨噬细胞(F4/80 + PD-L1 + )的代表性流式细胞图(n=5)。

(G) Steady-state RNA velocity of m-MDSCs, Ly6c+ monocytes, and M1/M2 macrophages.

(G) m-MDSCs、Ly6c + 单核细胞及 M1/M2 巨噬细胞的稳态 RNA 速率分析。

Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each spot representing one subject. Statistical significance was assessed by two-sided Student’s t test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01. NS, not significant. See also Figures S6 and S7.

数据以均值±标准差表示,每个圆点代表一个样本。统计学显著性采用双侧 Student t 检验评估。∗p < 0.05,∗∗p < 0.01。NS 表示无统计学意义。另见 Figures S6 和 S7 。

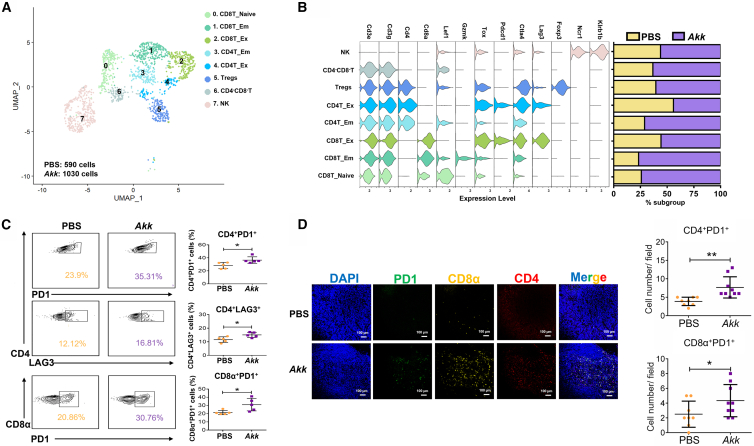

Effector memory CD4+/CD8+ T cells are increased in tumors of Akk-treated mice

Akk 处理小鼠肿瘤中效应记忆 CD4 + /CD8 + T 细胞数量增加

Next, we examined the effect of Akk on T cells by analyzing various T cell clusters (Figure 5A). In parallel with the decrease in m-MDSCs and M2 macrophages in the Akk-treated groups, as shown in Figure 4, we found increases in effector memory CD4+ cells, naive and effector memory CD8+ T cells, and CD4−CD8− double-negative T cells in the tumors of the Akk-treated groups (Figure 5B). We also showed an increase in populations of exhausted CD4+ T cells (CD4+PD1+ and CD4+LAG3+) and exhausted CD8+ T cells (CD8α+PD1+) (Figure 5C) using flow cytometry analysis. Consistently, we showed increased infiltration of CD4+PD1+ and CD8α+PD1+ cells in the tumors of Akk-treated groups by multiplexed immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis (Figure 5D). Concurrently, we found that Akk alters the immune-suppressive microenvironment, favoring T cell function by suppressing immune-suppressive cytokines, including Cxcl1, Ccl2, and Cxcl10, by qPCR analysis (Figure S8).

接着,我们通过分析各类 T 细胞亚群来考察 Akk 对 T 细胞的影响(图 0#A)。与 Akk 处理组中 m-MDSCs 和 M2 型巨噬细胞减少的趋势一致(如图 1#所示),我们发现该组肿瘤组织中效应记忆 CD4#细胞、初始及效应记忆 CD8#T 细胞、以及 CD4#CD8#双阴性 T 细胞均有所增加(图 6#B)。流式细胞术分析还显示,耗竭型 CD4#T 细胞(CD4#PD1#和 CD4#LAG3#)与耗竭型 CD8#T 细胞(CD8α#PD1#)的群体也有所增多(图 15#C)。多重免疫组化(IHC)分析同样证实,Akk 处理组肿瘤组织中 CD4#PD1#和 CD8α#PD1#细胞的浸润程度增强(图 20#D)。同时,qPCR 分析表明 Akk 通过抑制 Cxcl1、Ccl2 和 Cxcl10 等免疫抑制性细胞因子,改变了免疫抑制微环境,从而有利于 T 细胞功能发挥(图 21#)。

Figure 5. 图 5.

The effect of Akk administration on CD4/CD8 in tumors of Akk-treated mice

阿克曼氏菌给药对治疗组小鼠肿瘤中 CD4/CD8 的影响

(A) UMAP plot shows 8 clusters of NK and T cells, including CD8T_Naive, CD8T_EM, CD8_Ex, CD4T_EM, CD4T_Ex, Tregs, CD4−CD8− cells, and NK cells and doublets, by scRNA-seq based on their marker expression.

(A) UMAP 图基于单细胞 RNA 测序标记表达,展示了 8 个 NK 细胞和 T 细胞簇群,包括初始 CD8T 细胞、效应记忆 CD8T 细胞、耗竭型 CD8T 细胞、效应记忆 CD4T 细胞、耗竭型 CD4T 细胞、调节性 T 细胞、CD4 − CD8 − 双阳性细胞、NK 细胞以及双联体细胞。

(B) Violin plots displayed the marker genes for each immune cell cluster. Bar plot showing increases in CD4−CD8− T cells, effector memory CD4+ cells, and naive and effector memory CD8+ T cells in the tumors of the Akk-treated groups.

(B) 小提琴图展示各免疫细胞簇的标志基因。条形图显示 Akk 治疗组肿瘤中 CD4 − CD8 − T 细胞、效应记忆 CD4 + 细胞以及初始和效应记忆 CD8 + T 细胞的增加。

(C) Representative flow cytometry plots of CD4+PD1+/CD4+LAG3+ and CD8α+PD1+ T cells in the PBS- and Akk-treated groups (n = 5).

(C) PBS 组与 Akk 治疗组中 CD4 + PD1 + /CD4 + LAG3 + 及 CD8α + PD1 + T 细胞的代表性流式细胞术图谱(n=5)。

(D) Multiplex IF staining showed increased infiltration of CD4+PD1+ and CD8α+PD1+ populations in the Akk-treated group. PD1 (green), CD8α (orange), CD4 (red), and DAPI staining (blue). Scale bar, 100 μm.

(D) 多重免疫荧光染色显示 Akk 治疗组中 CD4 + PD1 + 与 CD8α + PD1 + 细胞群浸润增加。PD1(绿色)、CD8α(橙色)、CD4(红色)及 DAPI 染色(蓝色)。比例尺为 100 微米。

Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each spot representing one subject. Statistical significance was assessed by two-sided Student’s t test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01. See also Figure S8.

数据以均值±标准差表示,每个圆点代表一个样本。统计学显著性采用双尾 Student t 检验评估。∗p < 0.05,∗∗p < 0.01。另见 Figure S8 。

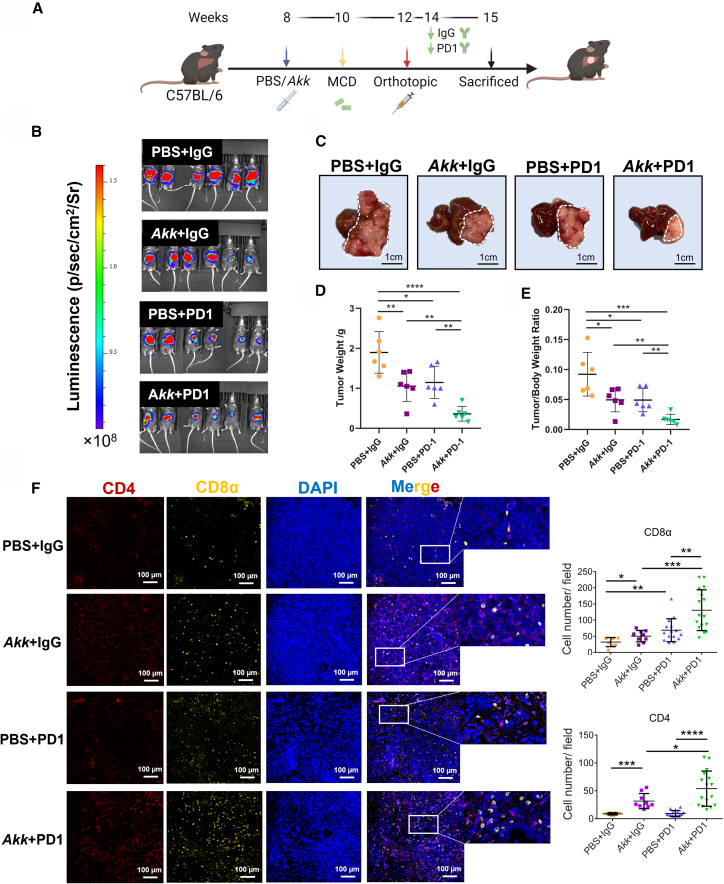

Combination treatment with Akk and PD1 suppressed the growth of the MAFLD-HCC mouse models

Akk 与 PD1 联合治疗抑制了 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型的肿瘤生长

Given the observation showing the role of Akk in the promotion of T cell infiltration and activity in Figure 5, we next examined the therapeutic efficacy of Akk in combination with PD1 in three MAFLD-HCC models. Firstly, we evaluated the effect of Akk supplementation in potentiating the effect of PD1 treatment in an orthotopic MAFLD-HCC mouse model fed with MCD diet (Figure 6A). Treatment with Akk and PD1 led to the maximal suppression of tumor growth, indicating that Akk treatment synergizes with PD1 treatment and is effective against liver tumors in vivo (Figures 6B–6E). We observed an increase in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in both the Akk-treated and combination treatment groups (Figure 6F). To rule out the possibility of a tumor-specific effect, we utilized another mouse HCC cell line, Hep55.1c, which was injected directly into the left liver lobe of mice fed with MCD diet (Figure S9A). We observed that the combination of Akk and PD1 treatment exerted the maximal suppression of HCC tumor growth (Figures S9B–S9D). Furthermore, we further rule out the possibility of diet-specific effect by evaluating the combination effect of Akk and PD1 in the same orthotopic model in mice fed with HFHC diet (Figure S10A).27 Consistent with the MCD diet model, we also showed that Akk in combination with PD1 treatment exerted maximal growth-suppressive effect in HCC tumor growth in the HFHC diet model (Figure S10B). Akk consistently delayed the progression of MAFLD (Figure S10C) with decrease in m-MDSCs (Figure S10D) and M2 macrophages (Figure S10E) but increase in infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ cells (Figure S11) in the combination treatment group. Lastly, we examine whether the enhanced efficacy of PD1 by Akk is MAFLD specific by employing the orthotopic HCC model of mice fed with normal diet. As shown in Figures S1C and S1D, our findings revealed that Akk demonstrated a tendency to suppress HCC tumors and improve the effectiveness of PD1 therapy, although the results did not reach statistical significance. This suggests that Akk supplementation may be more effective in restraining HCC tumor growth and complementing PD1 treatment in HCC with an MAFLD background.

鉴于观察到 Akk 在促进 Figure 5 中 T 细胞浸润和活性方面的作用,我们接下来在三种 MAFLD-HCC 模型中检测了 Akk 联合 PD1 的治疗效果。首先,我们在 MCD 饮食诱导的原位 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型中评估了补充 Akk 对增强 PD1 治疗效果的影响( Figure 6 A)。Akk 与 PD1 联合治疗实现了最大程度的肿瘤生长抑制,表明 Akk 治疗与 PD1 治疗具有协同作用,并在体内对肝脏肿瘤有效( Figures 6 B–6E)。我们观察到 Akk 治疗组和联合治疗组中 CD4 + 和 CD8 + T 细胞均有所增加( Figure 6 F)。为排除肿瘤特异性效应的可能性,我们使用了另一种小鼠 HCC 细胞系 Hep55.1c,将其直接注射至 MCD 饮食喂养小鼠的左肝叶( Figure S9 A)。研究发现 Akk 与 PD1 联合治疗对 HCC 肿瘤生长产生了最大程度的抑制效果( Figures S9 B–S9D)。 此外,我们通过评估高脂高胆固醇饮食(HFHC)小鼠原位模型中 Akk 与 PD1 的联合作用,进一步排除了饮食特异性效应的可能性(图 8A)。与 MCD 饮食模型一致,我们在 HFHC 饮食模型中也发现 Akk 联合 PD1 治疗对肝癌肿瘤生长具有最大抑制效果(图 10B)。联合治疗组中,Akk 持续延缓了 MAFLD 进展(图 11C),表现为 m-MDSCs(图 12D)和 M2 巨噬细胞(图 13E)减少,同时 CD4(图 14)和 CD8(图 15)细胞浸润增加(图 16)。最后,我们通过正常饮食小鼠的原位肝癌模型验证 Akk 增强 PD1 疗效是否具有 MAFLD 特异性。如图 17C 和 S1D 所示,尽管结果未达到统计学显著性,但 Akk 显示出抑制肝癌肿瘤并提升 PD1 治疗效果的倾向。这表明在 MAFLD 背景下,补充 Akk 可能更有效抑制肝癌肿瘤生长并增强 PD1 治疗效果。

Figure 6. 图 6.

The effect of Akk/PD1 on the suppression of tumor growth in an orthotopic MAFLD-HCC mouse model

Akk/PD1 对原位 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型中肿瘤生长的抑制作用

(A) Schematic diagram of the treatment regimen of Akk (5 × 109 colony-forming units), PD1 (5 mg/kg), and the combined treatment (Akk+PD1) group.

(A) Akk(5×10 9 菌落形成单位)、PD1(5 毫克/千克)及联合治疗组(Akk+PD1)的治疗方案示意图。

(B) Bioluminescence imaging of luciferase in C57BL/6 mice in 4 treatment groups, including PBS + IgG (n = 6), Akk + IgG (n = 6), PBS + PD1 (n = 6), and Akk + PD1 (n = 6).

(B) C57BL/6 小鼠荧光素酶生物发光成像的 4 个治疗组,包括 PBS + IgG(n = 6)、Akk + IgG(n = 6)、PBS + PD1(n = 6)和 Akk + PD1(n = 6)。

(C) Representative images of MAFLD-HCC tumors in the four treatment groups are shown. Scale bar, 1 cm.

(C) 四组治疗中 MAFLD-HCC 肿瘤的代表性图像如图所示。比例尺为 1 厘米。

(D and E) (D) Graphs showing the tumor weight and (E) liver/body weight ratio generated from mice at the endpoint (n = 6).

(D 和 E)(D)图表显示终点时小鼠的肿瘤重量和(E)肝脏/体重比值(n=6)。

(F) Increased infiltration of CD4+ and CD8α+ T cells in Akk-treated groups. CD4 (red), CD8α (orange), and DAPI staining (blue). Scale bar, 100 μm.

(F) 经 Akk 处理的组别中 CD4 + 和 CD8α + T 细胞浸润增加。CD4(红色)、CD8α(橙色)及 DAPI 染色(蓝色)。比例尺为 100 微米。

Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each spot representing one subject. Statistical significance was assessed by two-sided Student’s t test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. See also Figures S9–S12.

数据以均值±标准差表示,每个点代表一个样本。统计学显著性采用双尾 Student t 检验评估。∗p < 0.05,∗∗p < 0.01,∗∗∗p < 0.001,∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001。另见 Figures S9–S12 。

Akk as a crucial bacterium in the regulation of PD1 treatment sensitivity

作为调节 PD1 治疗敏感性的关键细菌

To further investigate the role of Akk in determining PD1 sensitivity, 6-week-old C57BL/6 male mice were used for fecal microbiota transfer (FMT) using antibiotic cocktail for 2 weeks. After 2 weeks of treatment, we conducted an FMT from PD1 responder patients with high abundance of Akk in an orthotopic MAFLD-HCC mouse model (Figure S12A). The treatment FMT from PD1 responder patients together with PD1 significantly impacted HCC tumor growth and showed a tendency to enhance the effectiveness of PD1 therapy (Figure S12B). Strikingly, co-administration of Akk with FMT showed the significant tumor-suppressive effect in combination with PD1 treatment (Figure S12B). This study highlights the importance of Akk as a key bacterial species among the gut microbiota of PD1 responder patients in regulating the sensitivity of PD1 treatment.

为深入探究 Akk 在决定 PD1 敏感性中的作用,我们采用 6 周龄 C57BL/6 雄性小鼠,使用抗生素混合物进行为期 2 周的粪便微生物群移植(FMT)。治疗两周后,我们在原位 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型中实施了来自 Akk 高丰度 PD1 应答患者的 FMT(图 0#A)。来自 PD1 应答患者的治疗性 FMT 联合 PD1 显著抑制了 HCC 肿瘤生长,并显示出增强 PD1 治疗效果的倾向(图 1#B)。值得注意的是,Akk 与 FMT 联合给药时,与 PD1 治疗协同产生了显著的肿瘤抑制效应(图 2#B)。本研究揭示了 Akk 作为 PD1 应答患者肠道菌群中关键菌种,在调控 PD1 治疗敏感性方面的重要性。

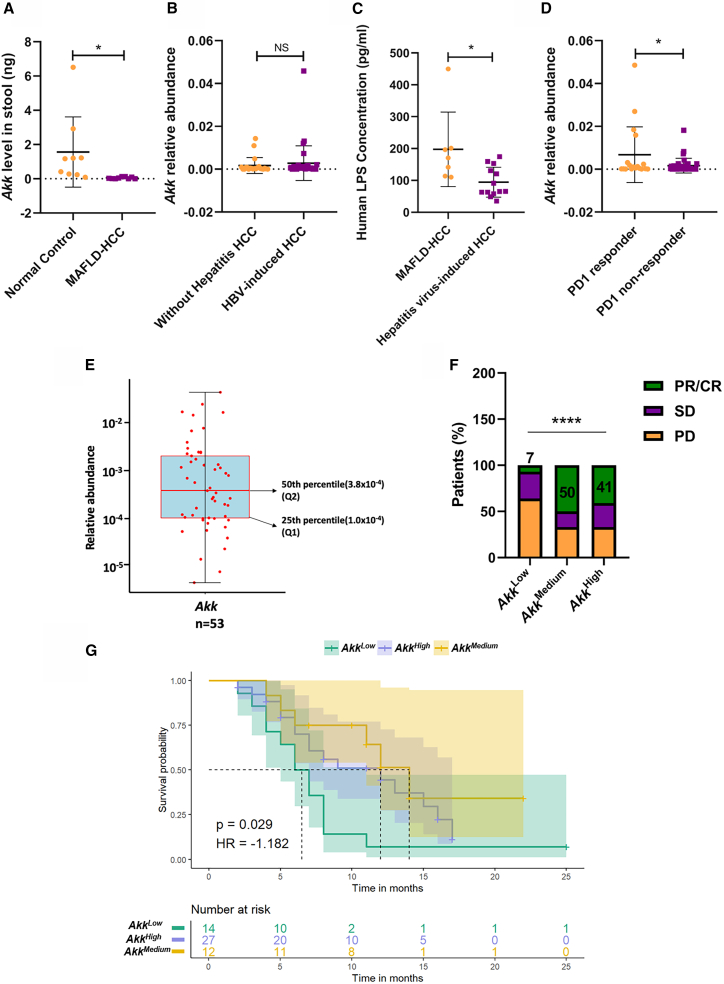

Clinical relevance of Akk in MAFLD-HCC and PD1 sensitivity

Akk 在 MAFLD-HCC 与 PD1 敏感性中的临床相关性

To examine whether the role of Akk in MAFLD-HCC is clinically relevant, we analyzed fecal samples from HCC patients at the Fifth Medical Center of PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table S1. Akk was found to be more abundant in the normal control group than in MAFLD-HCC patients (Figure 7A) by qPCR analysis. Interestingly, we found that there is no significant difference in the relative expression of Akk between HCC patients with non-hepatitis virus and HBV-induced HCC patients in a publicly available dataset (NCBI: PRJNA428932)28 (Figure 7B). This result suggests that hepatitis-induced HCC also did not affect Akk levels. Consistent with the in vivo findings shown in Figure S5F, increased detection of LPS was observed in the plasma of MAFLD-HCC patients with lower expression of Akk (Figure 7C). Next, we examined the role of Akk in the treatment response to ICI therapy and the outcomes of patients with HCC. A total of 53 PD1-treated patients were screened (Table S2); 18 patients were enrolled in the PD1 responder group, and 35 patients were enrolled in the PD1 non-responder group. Strikingly, the analysis from metagenomic sequencing of Akk showed that the PD1 responder group patients had a higher Akk relative abundance than the PD1 non-responder group patients (Figure 7D). We further explored whether Akk was associated with patient survival by dividing HCC patients into three groups according to the relative abundance of Akk levels: AkkHigh, AkkMedium, and AkkLow. Based on the relative abundance of Akk in patients, we divided the patients at a relative abundance greater than the 50th percentile (3.8 × 10−4) into the AkkHigh group. Then, the next half of patients was grouped into AkkMedium and AkkLow in the 25th percentile (1.0 × 10−4) (Figure 7E) like the study of Derosa L. et al.29 The percentage of patients with complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) was higher in the AkkHigh group than in the AkkLow group (41% vs. 7%, Figure 7F). Furthermore, AkkHigh and AkkMedium patients showed a better progression-free survival than their AkkLow counterparts (Figure 7G). Our findings suggest that the enrichment of Akk might enhance the clinical response to PD1 treatment and prolong patient survival. Akk can be a predictive factor for the survival benefit of HCC patients receiving immunotherapy.

为探究 Akk 在 MAFLD-HCC 中的作用是否具有临床相关性,我们分析了中国人民解放军总医院第五医学中心肝癌患者的粪便样本。患者特征总结见 Table S1 。通过 qPCR 分析发现,正常对照组中 Akk 的丰度高于 MAFLD-HCC 患者( Figure 7 A)。值得注意的是,我们在公开数据集(NCBI: PRJNA428932)中发现,非肝炎病毒导致的 HCC 患者与 HBV 诱导的 HCC 患者之间 Akk 相对表达量无显著差异( 28 , Figure 7 B),这一结果表明肝炎诱发的 HCC 同样不影响 Akk 水平。与 Figure S5 F 所示的体内实验结果一致,在 Akk 低表达的 MAFLD-HCC 患者血浆中观察到 LPS 检测值升高( Figure 7 C)。随后我们考察了 Akk 对 ICI 治疗反应及 HCC 患者预后的影响,共筛选出 53 例接受 PD1 治疗的患者( Table S2 ),其中 18 例纳入 PD1 应答组,35 例纳入 PD1 无应答组。 值得注意的是,通过对 Akk 菌的宏基因组测序分析发现,PD1 应答组患者的 Akk 菌相对丰度高于非应答组患者(图 7D)。我们进一步探究 Akk 菌是否与患者生存期相关,将肝癌患者按 Akk 菌相对丰度水平分为三组:Akk 高组、Akk 中组和 Akk 低组。根据患者体内 Akk 菌相对丰度,我们将丰度高于 50 百分位数(3.8×10^5)的患者归入 Akk 高组,随后将剩余患者按 25 百分位数(1.0×10^5)分为 Akk 中组和 Akk 低组(图 16E),该方法参照了 Derosa L.等学者的研究方案。数据显示,Akk 高组患者获得完全缓解(CR)或部分缓解(PR)的比例显著高于 Akk 低组(41% vs. 7%,图 20F)。此外,Akk 高组和中组患者的无进展生存期较 Akk 低组患者更优(图 24G)。本研究结果表明,Akk 菌的富集可能增强 PD1 治疗的临床响应并延长患者生存期。 阿克曼菌可作为预测肝癌患者免疫治疗生存获益的指标。

Figure 7. 图 7.

Association between Akk and PD1 responses in HCC patients

阿克曼氏菌与肝癌患者 PD1 治疗反应的相关性

(A) Expression of Akk was examined in the MAFLD-HCC (n = 9) and normal control groups (n = 9) using qPCR analysis.

(A) 采用 qPCR 分析法检测 MAFLD-HCC 组(n=9)与正常对照组(n=9)中 Akk 的表达水平。

(B) Relative abundance of Akk was examined in the group with HBV-induced HCC (n = 35) and the group without hepatitis HCC (n = 22) using 16S rRNA analyses.

(B) 通过 16S rRNA 分析检测 HBV 诱导型 HCC 组(n=35)与非肝炎型 HCC 组(n=22)中 Akk 的相对丰度。

(C) By ELISA, the human plasma LPS level was significantly increased in the MAFLD-related HCC groups (n = 9) compared to that in the hepatitis virus-induced HCC groups (n = 20).

(C) ELISA 检测显示,与肝炎病毒诱导型 HCC 组(n=20)相比,MAFLD 相关 HCC 组(n=9)的人血浆 LPS 水平显著升高。

(D) Analysis of metagenomic sequencing of Akk relative abundance in the PD1 responder (n = 18) and PD1 non-responder groups (n = 35).

(D) 对 PD1 应答组(n=18)与 PD1 无应答组(n=35)进行 Akk 相对丰度的宏基因组测序分析。

(E) Distribution of patients with the relative abundance of Akk. The midline of the boxplots corresponds to the 50th percentile. The lower hinges of the boxplots correspond to the 25th percentile.

(E)患者中 Akk 相对丰度的分布情况。箱线图中线对应第 50 百分位数。箱线图下铰链对应第 25 百分位数。

(F) The percentage of patients with different responses to PD1 treatment among the AkkHigh, AkkMedium, and AkkLow groups.

(F) Akk High 组、Akk Medium 组和 Akk Low 组患者对 PD1 治疗产生不同反应的比例分布

(G) Progression-free survival depended on the relative abundance of Akk. (p = 0.029, hazard ratio [HR] = −1.182).

(G) 无进展生存期与 Akk 菌相对丰度相关(p = 0.029,风险比[HR] = −1.182)

Data are presented as mean ± SD, with each spot representing one subject. Statistical significance was assessed by two-sided Student’s t test in (A)–(D). Statistical significance was assessed by chi-squared test in (E). Statistical significance was assessed by log rank test in (F). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. NS, not significant. See also Tables S1–S3.

数据以均值±标准差表示,每个点代表一个受试者。(A)-(D)采用双尾 Student t 检验评估统计学显著性;(E)采用卡方检验评估统计学显著性;(F)采用时序检验评估统计学显著性。∗p < 0.05,∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001。NS 表示无统计学意义。另见 Tables S1–S3 。

Discussion 讨论

The anti-tumor potential of probiotics has been demonstrated in gastrointestinal cancers.13,14,15 Nonetheless, studies on the use of probiotics in the prevention or treatment of HCC remain limited. In the present study, we found that Akk is crucial for the development of MAFLD-related HCC. Daily supplementation with Akk not only suppressed tumor growth in the NASH background but also, most importantly, complemented PD1 treatment. Clinically, Akk can potentially serve as a biomarker for the prediction of the PD1 response. By scRNA-seq coupled with flow cytometry analysis, our data provide an insight into how Akk shapes the tumor immune microenvironment in the liver with a NASH background, thereby regulating T cell activity. Overall, this study demonstrates the potential of the application of Akk in combination with current immune checkpoint therapies in MAFLD-related HCC.

益生菌的抗肿瘤潜力已在胃肠道癌症中得到证实。 13 14 15 然而,关于使用益生菌预防或治疗肝细胞癌(HCC)的研究仍然有限。本研究发现,Akkermansia muciniphila(Akk)对代谢相关脂肪性肝病(MAFLD)相关 HCC 的发展至关重要。每日补充 Akk 不仅能在非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(NASH)背景下抑制肿瘤生长,更重要的是能增强 PD1 治疗效果。临床上,Akk 有望作为预测 PD1 治疗反应的生物标志物。通过单细胞 RNA 测序结合流式细胞术分析,我们的数据揭示了 Akk 如何塑造 NASH 背景下肝脏肿瘤免疫微环境,从而调控 T 细胞活性。总之,本研究证明了 Akk 与现有免疫检查点疗法联合应用于 MAFLD 相关 HCC 的潜力。

Akk is a gram-negative bacterium living in anaerobic conditions and accounting for 1%–4% of the gut microbiota in healthy individuals.23

Akk plays a crucial role in the regulation of inflammation and is inversely correlated with inflammation in ulcerative colitis.30 A recent study showed that Akk reduced the levels of relevant blood markers for liver inflammation in liver injury in HFD/CCL4 mice31 and obese individuals.32 As obesity predisposes individuals to inflammation,33 recent studies have also been devised to investigate the correlation between Akk and obesity. Previous studies showed a negative relationship between the level of Akk and the development of obesity, in that the abundance of Akk is inversely proportional to obesity in animals and humans.34 Clinical studies also supported these findings and showed that the administration of Akk improved metabolic health in overweight and obese human volunteers.35 In addition, Akk also alleviates obesity-mediated metabolic syndromes, including diabetes.36 Given that obesity and diabetes are important risk factors for the development of MAFLD,37 administration of Akk was also reported to improve the severity of MAFLD.38 Consistently, a decrease in Akk abundance was observed in mice and patients with MAFLD.39,40 In this study, we also observed suppression of steatosis characteristics, which is possibly mediated through the inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis upon Akk treatment. Although the correlation between Akk and MAFLD has been established, how Akk is altered in the process of MAFLD-HCC development remains unclear. Recently, a decrease in Akk was found in MAFLD-related HCC mouse models, including STAM (signal transducing adaptor molecule) mice41 and Nlrp6−/− transgenic mice.42 Here, we found that Akk showed a significant tumor-suppressive effect in MCD diet-treated mice with injection of RIL-175. However, such effect is too drastic in other two MAFLD-HCC mouse models. The variation may be due to differences in the liver environment and the specific characteristics of the cell line used. Based on our data, Akk exerted an anti-tumor effect, as evidenced by the decrease in PCNA expression, which is in line with another study showing tumor-suppressive effect on ovarian cancer cell viability.43

阿克曼菌是一种生活在厌氧环境中的革兰氏阴性菌,在健康人群肠道菌群中占比 1%-4%。该菌株在炎症调控中起关键作用,其丰度与溃疡性结肠炎炎症程度呈负相关。最新研究表明,阿克曼菌能降低高脂饮食/四氯化碳诱导的肝损伤小鼠模型及肥胖人群肝脏炎症相关血液标志物水平。鉴于肥胖易诱发炎症,近期研究也开始探讨阿克曼菌与肥胖的关联。既往研究显示阿克曼菌水平与肥胖发展呈负相关,其丰度在动物和人类中均与肥胖程度成反比。临床研究证实了这一发现,表明补充阿克曼菌可改善超重及肥胖志愿者的代谢健康。此外,该菌株还能缓解肥胖介导的代谢综合征(包括糖尿病)。 鉴于肥胖和糖尿病是导致代谢相关脂肪性肝病(MAFLD)的重要风险因素,已有研究报道补充 Akkermansia muciniphila(Akk)可改善 MAFLD 的严重程度。与此一致的是,在 MAFLD 小鼠模型和患者体内均观察到 Akk 菌丰度下降。本研究还发现 Akk 治疗可能通过抑制胆固醇生物合成来缓解肝脏脂肪变性特征。尽管 Akk 与 MAFLD 的关联已得到证实,但 Akk 在 MAFLD 相关肝细胞癌(HCC)发展过程中的变化机制尚不明确。近期研究在 STAM(信号转导衔接分子)小鼠和 Nlrp6 转基因小鼠等 MAFLD 相关 HCC 模型中均检测到 Akk 菌减少。本研究发现,在 MCD 饲料喂养并注射 RIL-175 细胞的小鼠中,Akk 表现出显著的抑癌效应,但在另外两种 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型中该效应过于剧烈,这种差异可能源于肝脏微环境及所用细胞系特性的不同。 根据我们的数据,Akk 表现出抗肿瘤效果,PCNA 表达下降证实了这一点,这与另一项显示其对卵巢癌细胞活力具有抑制效应的研究结果一致。 43

Next, we examined the possible mechanism of Akk-mediated tumor suppression. Accumulating evidence has shown that Akk regulates cellular immunity by regulating intestinal membrane integrity.44 Consistently, we found that Akk repaired the intestinal lining, which was accompanied by a decrease in the flux of LPS. LPS is not only regarded as an important regulator of innate immune cells45 but also reported to be increased in NASH patients.46 Therefore, we hypothesize that Akk regulates innate immune cells by regulating the flux of LPS in an HCC model with a NASH background. We clearly observed suppression of m-MDSCs but not PNM-MDSCs in the Akk-treated group by scRNA-seq analysis. Similarly, Zhang et al. showed the involvement of m-MDSCs in MAFLD development.24 By GSEA, we found suppression of the NF-κB pathway with a decrease in TLR2 expression in m-MDSCs. These data, in addition to the reported role of TLR2-NF-κB in the expansion of m-MDSCs,25,26 suggest the effect of Akk in the suppression of m-MDSC populations via the NF-κB signaling pathway. By IHC analysis, we demonstrated a significant decrease in the number of TLR2+ MDSCs upon Akk treatment. Along with this change, m-MDSCs in the Akk group functionally suppressed M2 polarization and differentiation of Ly6C+ monocytes. While our findings indicate that TLR2+ MDSCs play a role in facilitating LPS-mediated M2 macrophage polarization, additional research utilizing mice with myeloid-specific TLR2 knockout is necessary to elucidate the precise mechanism underlying this process. Recent report highlights the role of the MUL (mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin protein ligase) gene in mucin usage and colon cholesterol biosynthesis through the creation of Akk mutants.47 It is worth exploring the influence of the MUL gene on MAFLD progression and anti-tumor immunity in our animal models. Consistent with the decrease in populations of the two groups of immune-suppressive cells, scRNA-seq revealed corresponding increases in naive CD8+ T cells, effector memory CD8+ T cells, effector memory CD4+ cells, and double-negative T cells in the tumors of the Akk-treated groups. Other studies reported the involvement of hepatic NKT (natural killer T) cells in steatohepatitis-associated hepatocarcinogenesis.48,49 In addition, we showed increased infiltration of CD4+PD1+ and CD8+PD1+ cells in the tumors of the Akk-treated group. Despite their functional exhaustion, these T cells were previously shown to exhibit enhanced tumor control and demonstrate responsiveness to PD1 inhibition.50 These solid data provide a therapeutic basis to examine the effect of Akk in combination with PD1 in an MAFLD-HCC model. Using the same mouse HCC model with a NASH background that was refractory to PD1 treatment,51 we showed that Akk in combination with PD1 led to the maximal suppression of tumor growth, with infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ cells. The effect of PD1 potentiation may be mediated via MAFLD reduction via Akk supplementation. Nevertheless, the data shown in Figures S9 and S10 indicate that Akk by itself had only a marginal effect on tumor inhibition in two additional MAFLD-HCC mouse models. Based on these data, we believe that the reduction of m-MDSC and M2 macrophages might be the key factor in enhancing the response to PD1 treatment. Our result may provide a therapeutic avenue for the treatment of HCC with a NASH background, as it was reported that immunotherapy is ineffective for this type of HCC in both murine models and human patients.52

接着,我们探究了 Akk 介导的肿瘤抑制可能机制。现有证据表明,Akk 通过调节肠道黏膜完整性来调控细胞免疫。与此一致的是,我们发现 Akk 能修复肠道屏障,同时伴随 LPS 通量的降低。LPS 不仅被视为先天免疫细胞的重要调节因子,也有报道显示其在 NASH 患者体内水平升高。因此,我们推测在 NASH 背景的 HCC 模型中,Akk 通过调节 LPS 通量来调控先天免疫细胞。通过单细胞 RNA 测序分析,我们明确观察到 Akk 治疗组中 m-MDSCs(而非 PMN-MDSCs)受到抑制。类似地,张等人研究证实 m-MDSCs 参与 MAFLD 的发展进程。通过 GSEA 分析,我们发现 m-MDSCs 中 TLR2 表达下降伴随 NF-κB 通路抑制。这些数据结合已报道的 TLR2-NF-κB 通路在 m-MDSCs 扩增中的作用,提示 Akk 可能通过 NF-κB 信号通路抑制 m-MDSCs 群体。免疫组化分析进一步证实,Akk 处理后 TLR2 阳性 MDSCs 数量显著减少。 伴随这一变化,Akk 组中的 m-MDSCs 在功能上抑制了 Ly6C 单核细胞的 M2 极化和分化。虽然我们的研究结果表明 TLR2 MDSCs 在促进 LPS 介导的 M2 巨噬细胞极化中发挥作用,但还需要利用髓系特异性 TLR2 敲除小鼠进行更多研究来阐明这一过程的确切机制。最新报告通过构建 Akk 突变体,强调了 MUL(线粒体 E3 泛素蛋白连接酶)基因在黏蛋白利用和结肠胆固醇生物合成中的作用。值得在我们的动物模型中探索 MUL 基因对 MAFLD 进展和抗肿瘤免疫的影响。与两组免疫抑制细胞数量减少相一致的是,单细胞 RNA 测序显示 Akk 治疗组肿瘤中初始 CD8 T 细胞、效应记忆 CD8 T 细胞、效应记忆 CD4 细胞和双阴性 T 细胞相应增加。其他研究报告了肝脏 NKT(自然杀伤 T)细胞参与脂肪性肝炎相关肝癌发生的过程。 此外,我们发现 Akk 处理组肿瘤中 CD4+PD1+和 CD8+PD1+细胞的浸润增加。尽管这些 T 细胞存在功能耗竭,但先前研究表明它们能增强肿瘤控制能力并对 PD1 抑制产生应答。这些坚实数据为研究 Akk 联合 PD1 在 MAFLD-HCC 模型中的疗效提供了治疗基础。在使用同样对 PD1 治疗耐药的 NASH 背景小鼠 HCC 模型时,我们发现 Akk 与 PD1 联用能最大程度抑制肿瘤生长,并促进 CD4+和 CD8+细胞的浸润。PD1 疗效的增强可能是通过补充 Akk 减少 MAFLD 来实现的。然而,图表 Figures S9 和 S10 数据显示,在另外两种 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型中,Akk 单独使用对肿瘤抑制仅有边际效应。基于这些数据,我们认为 m-MDSC 和 M2 巨噬细胞的减少可能是增强 PD1 治疗应答的关键因素。 我们的研究结果可能为治疗非酒精性脂肪性肝炎相关肝细胞癌提供新的治疗途径,因为已有报道表明免疫疗法在小鼠模型和人类患者中对这类肝癌均无效。 52

To further evaluate the significance of Akk in sensitization of PD1 therapy, we established antibiotic-treated mice and conducted FMT from PD1 responder patients enriched with Akk with co-administration of PD1 in the MAFLD-HCC mouse model. The treatment with FMT from PD1 responder patients showed a trend of potentiating the PD1 therapy, which is in line with previous study showing the sensitization of PD1 treatment upon FMT.53 The efficiency can be further improved by increasing the limitation of sample size, treatment frequency, and FMT quantity. Notwithstanding, the combination of Akk with FMT demonstrated a significant tumor-suppressive effect when administered with PD1 treatment, emphasizing the significance of Akk as a crucial bacterial species among the gut microbiota of PD1 responder patients in modulating the responsiveness of PD1 treatment. Currently, there are limited biomarkers to determine the efficacy of PD1 treatment. Among these markers, PDL1 is one of the reliable markers used in the clinic. Recently, increasing attention has been given to the use of the gut microbiome for the prediction of the PD1 response. The abundance of Akk was reported to be a biomarker for the prediction of the PD1 response in non-small cell lung cancer patients.29 With a small cohort of HCC patients with HBV background upon PD1 treatment, we showed that patients with a better PD1 response showed a higher abundance of Akk. This result suggests the potential use of Akk as a biomarker for the prediction of the PD1 response in these HCC patients. Nevertheless, our research has a constraint as we were unable to collect enough stool samples from HCC patients with MAFLD. Future study is needed to validate the specificity of Akk as a biomarker for predicting PD1 responsiveness in HCC patients with MAFLD etiology. Nonetheless, our animal data indicated that Akk supplementation may be more effective in restraining HCC tumor growth and complementing PD1 treatment in orthotopic mouse model with injection of RIF175 with MAFLD background. The preferential effect can also be attributed to the high responsiveness of this cell line in a mouse model lacking an MAFLD background.

为进一步评估 Akk 菌在增强 PD1 疗法敏感性中的重要性,我们在 MAFLD-HCC 小鼠模型中建立了抗生素处理组,并实施了来自富含 Akk 菌的 PD1 应答患者的粪便微生物移植(FMT),同时联合 PD1 治疗。来自 PD1 应答患者的 FMT 治疗显示出增强 PD1 疗效的趋势,这与先前研究中 FMT 对 PD1 治疗的增敏作用一致。通过增加样本量限制、治疗频率和 FMT 剂量,可进一步提升该方案的疗效。值得注意的是,当 Akk 菌与 FMT 联合 PD1 治疗时,展现出显著的肿瘤抑制效果,这突显了 Akk 菌作为 PD1 应答患者肠道菌群中关键菌种对调节 PD1 治疗反应的重要性。目前临床上可用于评估 PD1 疗效的生物标志物有限,其中 PDL1 是可靠的临床指标之一。近年来,利用肠道微生物组预测 PD1 治疗反应的研究正受到越来越多的关注。 据报道,Akk 菌丰度可作为预测非小细胞肺癌患者 PD1 治疗反应的生物标志物。 29 通过对接受 PD1 治疗的 HBV 相关肝癌患者小队列研究,我们发现对 PD1 治疗反应较好的患者体内 Akk 菌丰度较高。这一结果表明 Akk 菌有望作为预测此类肝癌患者 PD1 治疗反应的生物标志物。然而,我们的研究存在局限性,因为未能收集足够多 MAFLD 相关肝癌患者的粪便样本。未来需要进一步研究验证 Akk 菌作为预测 MAFLD 病因肝癌患者 PD1 治疗反应特异性生物标志物的价值。尽管如此,我们的动物实验数据显示,在 MAFLD 背景下注射 RIF175 构建的原位小鼠模型中,补充 Akk 菌可能更有效抑制肝癌肿瘤生长并增强 PD1 治疗效果。这种优势效应也可能归因于该细胞系在非 MAFLD 背景小鼠模型中表现出的高反应性。

In conclusion, we provided a mechanistic insight into how Akk regulates the immune tumor environment by regulating two immune-suppressive cells in MAFLD-HCC, which provides a solid therapeutic basis for rational combination with PD1 for the treatment of this deadly disease. Finally, Akk may potentially serve as a noninvasive biomarker for the prediction of the PD1 response in HCC patients.

总之,我们揭示了 Akk 通过调控 MAFLD-HCC 中两种免疫抑制性细胞来调节肿瘤免疫微环境的机制,这为合理联合 PD1 治疗这一致命疾病提供了坚实的理论基础。最后,Akk 可能作为一种无创生物标志物,用于预测肝癌患者对 PD1 治疗的反应。

Limitations of the study

本研究的局限性

Due to the substantial cost associated with single-cell sequencing, the sample size for this analysis is currently limited. To enhance the study’s validity, it would be advantageous to expand the sample size more. Besides that, we need to validate the infiltration and activations of T cells by examining the quantity of effector CD4+/CD8+ T cells in different mice models via flow cytometry analysis. For the FMT experiment, the current study is limited by the number of stool samples from MAFLD-HCC patients. In the future, fecal donors should be stratified into AkkHigh and AkkLow groups to verify Akk as key microbiota for determining PD1 sensitivity. Our in vivo animal experiments demonstrated that Akk preferentially promotes PD1 therapy in treating MAFLD-HCC. However, our clinical correlation between Akk level and PD1 sensitivity predominantly involves HBV-positive HCC patients, which may contradict the findings of our animal experiments. Future research should focus on conducting more comprehensive animal studies to evaluate and contrast the PD1 sensitivity in animal models of HBV-induced HCC and MAFLD-HCC. In the future, it is necessary to recruit stool samples from patients with MAFLD-HCC to verify the role of Akk in relation to PD1 responsiveness.

由于单细胞测序成本高昂,当前分析样本量有限。为提高研究可靠性,扩大样本规模将更具优势。此外,我们需要通过流式细胞术检测不同小鼠模型中效应性 CD4 + /CD8 + T 细胞的数量,以验证 T 细胞的浸润与活化状态。在粪菌移植实验中,当前研究受限于 MAFLD-HCC 患者粪便样本数量。未来应将粪便供体分为 Akk High 与 Akk Low 组别,以验证 Akk 菌作为决定 PD1 疗效关键菌群的作用。我们的体内动物实验证实 Akk 菌能优先增强 PD1 疗法对 MAFLD-HCC 的疗效,但临床数据中 Akk 水平与 PD1 敏感性的相关性主要来自 HBV 阳性 HCC 患者,这可能与动物实验结果存在矛盾。后续研究应开展更系统的动物实验,对比评估 HBV 诱发 HCC 与 MAFLD-HCC 动物模型中 PD1 疗法的敏感性差异。 未来有必要收集 MAFLD-HCC 患者的粪便样本,以验证 Akk 菌与 PD1 治疗反应之间的关联作用。

Resource availability 资源可用性

Lead contact 主要联系人

More information and inquiries about resources and reagents should be directed to Prof. Terence Kin Wah Lee (terence.kw.lee@polyu.edu.hk), who will address your requests.

有关资源和试剂的更多信息及查询,请直接联系李建华教授(terence.kw.lee@polyu.edu.hk),他将处理您的请求。

Materials availability 材料可用性声明

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

本研究未产生新型独特试剂。

Data and code availability

数据与代码可用性声明

The bulk RNA sequencing, the 16S RNA sequencing, and the scRNA-seq datasets have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database repository and can be accessed using the accession numbers GSE242467, GSE242468, and GSE242469. All data were accessible to the public. There is no original code reported in this paper. For any further information needed to reanalyze the data, please contact the lead author, Prof. Terence Kin Wah Lee.

批量 RNA 测序数据、16S RNA 测序数据及单细胞 RNA 测序数据集已提交至 NCBI 基因表达综合数据库(GEO),可通过登录号 GSE242467 、 GSE242468 和 GSE242469 获取。所有数据均向公众开放。本文未报告原始代码。如需重新分析数据的其他信息,请联系通讯作者 Terence Kin Wah Lee 教授。

Acknowledgments 致谢

We thank the University Research Facility in Life Sciences at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University for providing and maintaining the equipment. We thank the Centralised Animal Facility at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the Centre for Comparative Medicine Research at The University of Hong Kong for supporting our animal studies. We thank Dr. Li Xiao Xing in the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University for providing the protocol for FMT experiment. We thank Dr. Jennifer Zhang Xiang in The Chinese University of Hong Kong for helpful discussion. We thank the Department of Pathology at The University of Hong Kong for the histopathology service. This study was supported by the Project of Strategic Importance in PolyU (1-ZE1Z), PolyU Internal Research Fund (1-WZAL), and Research Impact Fund (R5008-22F).

我们感谢香港理工大学生命科学研究设施提供并维护实验设备,感谢香港理工大学中央动物实验设施及香港大学比较医学研究中心对动物实验的支持。特别鸣谢中山大学附属第一医院李晓星博士提供粪菌移植实验方案,感谢香港中文大学张翔博士的有益讨论,同时感谢香港大学病理学系提供组织病理学服务。本研究获香港理工大学战略性重大项目(1-ZE1Z)、校内研究基金(1-WZAL)及研究影响基金(R5008-22F)资助。

Author contributions 作者贡献

X.Q.W., F.Y., K.P.S.C., and T.K.W.L. designed the experiment. X.Q.W., F.Y., K.P.S.C., C.O.N.L., R.W.H.L., W.C.S., and W.K.C. performed the experiment. X.Q.W., F.Y., K.P.S.C., C.O.N.L., K.K.H.S., M.M.L.L., D.W., S.M., Y.Y.L., and T.K.W.L. analyzed the data, and X.Q.W., F.Y., and K.P.S.C. wrote the paper. J.Y. and Y.Y.L. provided reagents and tissue samples for this study. S.M. provided HCC cell lines. Y.Y.L. and T.K.W.L. supervised the study. All authors contributed to the discussion of results and manuscript corrections.

X.Q.W.、F.Y.、K.P.S.C.和 T.K.W.L.设计了实验方案。X.Q.W.、F.Y.、K.P.S.C.、C.O.N.L.、R.W.H.L.、W.C.S.和 W.K.C.执行了实验操作。X.Q.W.、F.Y.、K.P.S.C.、C.O.N.L.、K.K.H.S.、M.M.L.L.、D.W.、S.M.、Y.Y.L.和 T.K.W.L.负责数据分析,X.Q.W.、F.Y.和 K.P.S.C.撰写了论文。J.Y.和 Y.Y.L.为本研究提供了试剂和组织样本。S.M.提供了肝癌细胞系。Y.Y.L.和 T.K.W.L.监督了研究进程。所有作者均参与了结果讨论及文稿修订工作。

Declaration of interests

利益声明

The authors declare no competing interests.

作者声明无竞争性利益关系

STAR★Methods STAR★方法

Key resources table 关键资源表

| REAGENT or RESOURCE 试剂或资源 | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies 抗体 | ||

| Anti-mouse CD45(APC) 抗小鼠 CD45(APC) | BD Biosciences | Cat#55984; RRID: AB_398672 货号#55984;RRID: AB_398672 |

| Anti-mouse CD4(PE-cy5) 抗小鼠 CD4(PE-cy5) | Biolegend Biolegend 公司 | Cat#100409; RRID: AB_312694 货号#100409;RRID: AB_312694 |

| Anti-mouse CD8α(Pacific Orange) 抗小鼠 CD8α(太平洋橙) |

Sysmex America 希森美康美国公司 | Cat#AJ277511; RRID: AB_3674194 货号 AJ277511 ;RRID:AB_3674194 |

| Anti-mouse PD1(BV711) 抗小鼠 PD1(BV711) | Biolegend 生物传奇公司 | Cat#135231; RRID: AB_2566158 货号 135231;研究资源标识符:AB_2566158 |

| Anti-mouse LAG3(FITC) 抗小鼠 LAG3 抗体(FITC 标记) | Thermo Fisher 赛默飞世尔科技 | Cat#11-2231-82; RRID: AB_257248 货号#11-2231-82;RRID: AB_257248 |

| Anti-mouse CD11b(BV421) 抗小鼠 CD11b(BV421) | Biolegend Biolegend 公司 | Cat#101235; RRID: AB_10897942 货号#101235;RRID: AB_10897942 |

| Anti-mouse Ly6C(APC) | Biolegend | Cat#128015; RRID: AB_1732076 |

| Anti-mouse Ly6G(FITC) | Biolegend | Cat#127605; RRID: AB_1236488 |

| Anti-mouse F4/80(APC/cy7) | Biolegend | Cat#123117; RRID: AB_893477 |

| Anti-mouse F4/80(FITC) | Biolegend | Cat#157309; RRID: AB_2876535 |

| Anti-mouse MHC-II(PE-Cy7) | Thermo Fisher | Cat#25-5321-82; RRID: AB_10870792 |

| Anti-mouse PD-L1(Qdot 800) | Thermo Fisher | Cat#S10455; RRID: AB_2556466 |

| Anti-mouse CD206(PerCp/cy5.5) | Biolegend | Cat#141715; RRID: AB_2561991 |

| Mouse MDSC Flow Cocktail 2 with Isotype Ctrl | Biolegend | Cat#147003; RRID: AB_3097688 |

| Anti-mouse PD1(RMP1-14) | Bio-X-Cell | Cat#BE0146; RRID: AB_10949053 |

| Rat IgG2a isotype control (2A3) | Bio-X-Cell | Cat#BE0089; RRID: AB_1107769 |

| Anti-Occludin | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-133256; RRID: AB_2298924 |

| Anti-Claudin 1 | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-166338; RRID: AB_2244863 |

| Anti-Claudin 4 | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-376643; RRID: AB_11149932 |

| Anti-ZO-1 | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-33725; RRID: AB_628459 |

| Anti-TLR2 | Abcam | Cat#sc-21759; RRID: AB_3674199 |

| Anti-CD11b | NOVUSBIO | Cat#NB110-89474; RRID: AB_1216361 |

| Anti-CD4 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#48274; RRID: AB_3076699 |

| Anti-CD8α | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#85336; RRID: AB_280005 |

| Anti-PD1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#43248; RRID: AB_2728836 |

| Anti-PCNA | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc-56; RRID: AB_628110 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Akk | American Type Culture Collection | Cat#BAA-835 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Plasma samples of HCC patients | Fifth Medical Center of the PLA General Hospital | N/A |

| Stool samples of HCC patients | Fifth Medical Center of the PLA General Hospital | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| DAPI | Akoya Biosciences | Cat#2181374 |

| Opal polymer HRP Mouse+Rabbit | Akoya Biosciences | Cat#ARH1001EA |

| Hematoxylin and eosin Y | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#318906 |

| BODIPY™ | Thermo Fisher | Cat#D3922 |

| D-Luciferin, Monopotassium Salt | Thermo Fisher | Cat#88293 |

| LIVE/DEAD Fixable Near-IR Dead Cell Stain Kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat# L23105 |

| QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit | QIAGEN | Cat#51804 |

| BlasTaq™ 2X PCR MasterMix | abm | Cat#G895 |

| Type II porcine mucin | Sigma‒Aldrich | Cat#84082-64-4 |

| Brain heart infusion (BHI) | BD Bioscience | Cat#237500 |

| Cysteine | Sigma‒Aldrich | Cat#52-90-4 |

| Chemical carcinogen diethylnitrosamine (DEN) | Sigma‒Aldrich | Cat#N0756 |

| High-fat diet (HFD) | Research diet | Cat#D12492 |

| High SA Fat High Sucrose Cholesterol(HFHC) | Specialty Feeds | Cat#SF1-078 |

| Dextran Sulfate Sodium (DSS) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#42867-5G |

| Ampicillin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#PHR2838 |

| Neomycin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#N1142 |

| Metronidazole | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#M1547 |

| Vancomycin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#V2002 |

| Mice Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Isolation Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-094-538 |

| Alcian blue solution | Cancer Diagnostics | Cat#SS1025P |

| Neutral red solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#72210 |

| Human LPS ELISA kit | CUSABIO | Cat#CSB-E09945h |

| Mouse LPS ELISA kit | CUSABIO | Cat#CSB-E13066m |

| LiquiColor® Enzymatic Tests for Triglycerides | Stanbio | Cat#2200 |

| LiquiColor® Enzymatic Tests for Cholesterol | Stanbio | Cat#1010 |

| QIAzol Lysis Reagent | QIAGEN | Cat#79306 |

| PrimeScriptTM RT Reagent Kit | Takara | Cat#RR037B |

| Fixation and Cell Permeabilization Kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat#88-8824-00 |

| RNease Plus Mini Kit | QIAGEN | Cat#74134 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Mouse bulk RNA sequencing | NCBI Gene expression omnibus (GEO) | GSE242467 |

| Mouse 16S RNA sequencing | NCBI Gene expression omnibus (GEO) | GSE242468 |

| Mouse single cell RNA sequencing | NCBI Gene expression omnibus (GEO) | GSE242469 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| RIL-175-luc | kindly provided by Professor Stephanie Ma | N/A |

| Hep55.1C | kindly provided by Professor Stephanie Ma | N/A |

| Raw264.7 | ATCC | Cat#TIB-71 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6J | The Chinese University of Hong Kong | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S3 for qPCR primer sequences | This paper | In this study |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 8.3.0 | GraphPad Software | N/A |

| FlowJo 10.0 | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| ImageJ | NIH | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

Experimental model and study participant details

Patients and samples

From December 2019 to March 2023, 88 patients with HCC were enrolled in this study from the Comprehensive Liver Cancer Center, Fifth Medical Center of the PLA General Hospital. Nine patients were diagnosed with MAFLD-related HCC according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) Clinical Practice Guidelines. Twenty HCC patients with hepatitis virus infection were included in the hepatitis virus-induced HCC group. A total of fifty-three HCC patients were treated with ICIs, 49% of them had radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE) before immunotherapy. Inclusion criteria included patients aged ≥18 years, both male and female, with ECOG performance status 0–1. The gender had no influence for the study. Patients’ characteristics are described in Tables S1 and S2. All patients were treated as per standard of care. Treatment responses were assessed by radiological evaluation every 6 weeks according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 standard. Patients with a complete response (CR), partial response (PR), or stable disease (SD) of ≥6 months were defined as the PD1 responder group, while patients with SD of <6 months or progressive disease (PD) were defined as the PD1 non-responder group. Plasma samples of nine MAFLD patients, twenty hepatitis virus-induced HCC were collected and storaged at −80°C for LPS ELISA analysis. Fresh fecal samples of nine MAFLD patients, twenty hepatitis virus-induced HCC were collected and stored at −80°C until DNA extraction to do the quantitative PCR analyses. Fifty-three fresh fecal samples of HCC patients using ICIs were collected and stored at −80°C until DNA extraction to do the metagenomics. Clinical samples were obtained from Prof. Yin Ying Lu at the Comprehensive Liver Cancer Center, The Fifth Medical Center of PLA General Hospital, Beijing. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for ethical review (KY-2021-12-35-1). All the institutional approvals were obtained for this study. Each patient provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Cell lines and cell culture

The murine HCC cell line RIL-175 stably expressing luciferase and Hep55.1C were kindly provided by Professor Stephanie Ma (University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, SAR) and were maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Raw264.7 cells (America Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in high-glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All cell lines used in this study were obtained between 2013 and 2020, and they were regularly authenticated by morphologic observation and AuthentiFiler STR (Invitrogen) as well as tested for the absence of mycoplasma contamination (MycoAlert, Lonza). Cells were used within 20 passages after thawing.

Mouse models

C57BL/6 male mice were purchased from The Chinese University of Hong Kong and housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions with a 12-h light-dark cycle at Centralized Animal Facilities (CAF) at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. All the above animal experiments were approved by and performed in accordance with the guidelines for the Use of Live Animals in Teaching and Research at Hong Kong Polytechnic University. All the animal experimentations were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

For the administration of Akk in mice, Akk culture was first centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 7 min to remove the undissolved mucin after 48 h of incubation. The supernatant was then transferred to a new falcon tube and centrifuged at 10000g for 10 min. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in anaerobic PBS in a concentration of 5 × 109 CFU and 200 μL was proceeded to oral gavage daily to each C57BL/6J mice.

To establish MAFLD-promoted HCC for 16S rRNA amplicon pyrosequencing, male mice were injected with the chemical carcinogen diethylnitrosamine (DEN) (Sigma‒Aldrich) at the age of 14 days and fed a high-fat diet (HFD) (60% kcal of fat, Research diet) for 32 weeks. For MAFLD-HCC mice model fed with HFHC, the C57BL/6 male mice were fed by HFHC diet (Modified AIN93G High SA Fat High Sucrose Cholesterol, Specialty Feeds, SF1-078) at 8 weeks of age. At 24 weeks, the mice received either Akk or PBS. Following 8 months of HFHC feeding, the mice exhibited progression from MAFLD to HCC tumor development. To establish the orthotopic MAFLD-HCC model fed with normal diet, male mice were fed normal diet, for 24 weeks prior to intrahepatic tumor injection with RIL-175 cells (5000 cells) and received Akk or PBS at 24 weeks. The luciferase signal of the injected cells and tumor growth were monitored weekly post-injection. To establish the orthotopic MAFLD-HCC model fed with MCD diet, male mice were fed a methionine and choline-deficient (MCD) diet (Research diet) for two weeks prior to intrahepatic tumor injection. Briefly, suspension of RIL-175 cells (5000 cells) and Hep55.1C cells (5000 cells) mixed with 50% Matrigel were orthotopically injected into the right lobe of the mouse liver. The luciferase signal of the injected cells and tumor growth were monitored weekly post-injection. To establish the orthotopic MAFLD-HCC model fed with HFHC, male mice were fed an HFHC diet for 24 weeks prior to intrahepatic tumor injection with RIL-175 cells (5000 cells) and received Akk or PBS at 24 weeks. To establish the Dextran Sulfate Sodium (DSS) mouse model, 8-week-old mice were administered 2% DSS for 7 days and subsequently received Akk or PBS for 2 weeks. Body weights were recorded at 3-day intervals, and liver and blood samples were collected on day 15. For the experiment involving the combination of Akk and PD1, the murine subjects were administered IgG2a (#BE0089) and anti-mouse PD1 (5 mg/kg; #BE0146), and tumor progression was monitored via luciferase signal post-administration. The subjects received anti-PD1 treatment for 10 days prior to euthanasia; subsequently, the tumors were excised for analysis.

Method details

Metabolomics analysis

Blood specimens were collected from mice and were kept on dry ice for the blood component separation and aliquoting before storage at −80°C until analysis. Plasma bile acids were analyzed by LC-MS/MS by using an UHPLC system (1290, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) coupled with a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent QQQ-MS 6438, USA). Bile acid metabolites from plasma samples were chromatographically separated on a 100 mm × 2.1 mm ACQUITY UPLC C8 column. The acquisition data was analyzed by The Beijing Genomics Institute for the peak integration, calibration equations and quantification of individual bile acids.

Metagenomic sequencing

Bacterial genomic DNA from 250 mg of fecal was extracted with the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Metagenomic sequencing was performed at the Beijing Genomics Institute (Shenzhen, China). Before constructing the DNA library, the concentration (≥12.5 μg/μL), integrity (central peak >20 kb), and purity (absence of protein, RNA, or other contaminants) were verified. Only samples that met these criteria were utilized to construct the library. Qualified libraries were sequenced using either DNBSEQ-G400 or DNBSEQ-T7. RCAs replicate single-stranded circular DNA molecules to form DNA nanoballs (DNBs) containing multiple DNA copies. DNBs were loaded onto the sequencing chips and sequenced. The default read length was PE150.

m-MDSC isolation and co-culture

Single-cell suspensions from mouse tumors were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Isolation of MDSC was carried out with mice Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, first, the cell suspension was incubated with an Anti-Ly-6G-Biotin antibody and Anti-Biotin MicroBeads. The cells were subsequently applied to an MACS Column, which retained magnetically labeled Gr-1highLy-6G+ cells. The unlabeled cells flowed through; this cell fraction contained Gr-1dimLy-6G– myeloid cells. Next, the pre-enriched Gr-1dimLy-6G– subpopulation was further purified. To this end, the cells were incubated with an Anti-Gr-1-Biotin antibody and Streptavidin Microbeads, and isolated by positive selection over two MACS Columns. Freshly isolated tumor m-MDSCs and Raw264.7 cells were co-cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 30% tumor cell medium and GM-SCF (10 ng/ml) for 72 h. The Raw264.7 cells were collected and stained with primary CD11b, CD206 and F4/80 antibodies for flow cytometry analysis. The isolated m-MDSCs were also collected for gene expression analysis.

Alcian blue staining

Dewaxed and rehydrated tissue sections were stained in 1% Alcian blue solution (SS1025P, Cancer Diagnostics, Inc., Birmingham, MI) for 5 min and subsequently counterstained in 0.1% Neutral red solution (72210, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 5 s. The tissue sections were then mounted and observed under microscopy.

Determination of LPS level

Human plasma was collected by centrifuging the whole blood at 3000 g at room temperature for 10 min. A commercial endotoxin assay (LAL Chromogenic Endpoint Assay) was performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty-seven plasma samples of HCC patients were collected from the Comprehensive Liver Cancer Center, Fifth Medical Center of the PLA General Hospital. The plasma samples were stored at −80°C until ELISA. Levels of LPS in human plasma were detected using ELISA kit (CUSABIO CSB-E09945h) and level of LPS in mice serum were detected using ELISA kit (CUSABIO CSB-E13066m) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Determination of serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels